Understanding bird sounds

Sonagrams

Visualising bird sounds

VISUALISING SOUND

Sonagrams

Bird identification has typically revolved around plumage colours, structural features and behaviour. Field guides and birding journals tend to concentrate more on visible features than on vocalisations

The following section introduces sonagrams (the ‘structure’ of bird sounds) and how to read them, bringing a visual and comparable standard for defining bird sounds.

Reading sonagrams

Bird sound has structure, but you can only see it in a sonagram (also known as a spectrogram). Sonagrams are simply graphic illustrations of sound, in the same way that graphs can illustrate a company’s share price. A sonagram traces the ups and downs of sounds across time. The higher on the page, the higher the pitch; the closer to the base line, the lower the pitch.

As a general rule, The Sound Approach uses sonagrams on a scale from 0 to 8 kHz on the vertical frequency axis, or sometimes up to 10 or 12 kHz if needed. For lower-pitched sounds such as hoots of owls, we may use only up to 2 kHz. We use a variety of time scales but ensure that sonagrams being compared are at exactly the same scale. We use colours to help in interpreting the sonagrams, and we can magnify some details to take a closer look.

With the right software, you can make sound recordings in the field, analyse them at home, and compare them with published recordings and sonagrams. Difficult identifications can be confirmed within hours. If you have a go, don’t forget to use the same scale when comparing any two sonagrams.

Terms & definitions

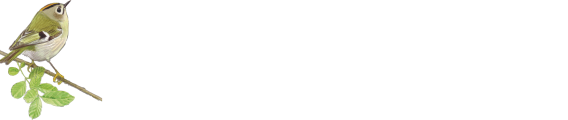

Peak frequency

The frequency that carries most power, i.e. the loudest part within the call. It is not necessarily the maximum frequency, nor in the middle of the call. As the loudest part within a call, it is the frequency that dominates the pitch (how high or low a call appears to sound). It can be measured automatically in many bioacoustics programs or measured by hand by visually inspecting a sonagram. In a black and white sonagram it is the part with the deepest black.

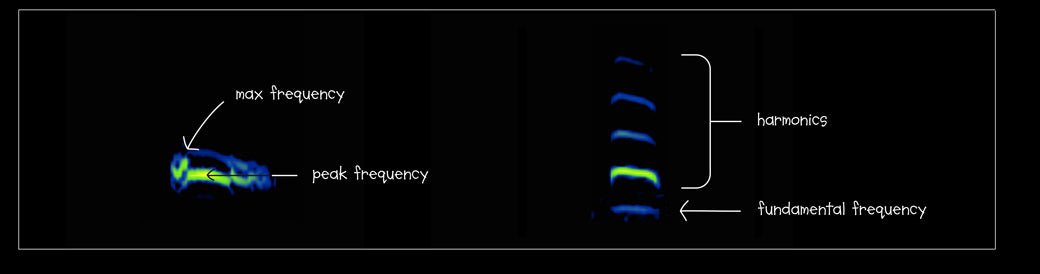

Frequency band

A descriptive term that makes most sense when looking at a sonagram. It describes a trace moving in time from left to right, inflected up or down as it goes. The term is most useful when describing calls with more than one band simultaneously, such as a European Robin’s nocturnal flight call.

Fundamental frequency

Traditionally defined as the lowest frequency component of a call. Harmonics are multiples of the fundamental frequency, and the fundamental is considered to be the first harmonic. In some calls, the fundamental can be strongly suppressed by the bird and therefore inaudible as well as being invisible in sonagrams (e.g., in many calls of Tree Pipits Anthus trivialis).

Harmonic

A component of a sound with a frequency that is a multiple of the basic or fundamental frequency. In sonagrams it usually appears as a copy of the ‘actual’ call, above it, and typically there are several. In calls that sound pure, the harmonics are very faint. In calls that sound nasal (e.g., a toy trumpet), several harmonics will have equally strong power. It is the relative strength of the various harmonics that determines the timbre of the call. Several types of frequency bands exist, but harmonics are always multiples of a basic frequency. A bird can also produce two signals at once, one with each syrinx or vocal organ. These can be entirely unrelated in their frequency contour and are not called harmonics.

Describing shapes in sonagrams

A ‘spike’

A brief, sharp frequency modulation pointing upwards from the baseline of an otherwise unmodulated frequency band. A classic example of spikes can be seen in most (but not all) Spotted Flycatcher nocturnal flight calls.

A ‘foreleg’

A near-vertical ascent at the start of a call, and the shape of this structure can be important for identifying certain species, e.g. wagtails Motacilla.

A ‘hindleg’

A near-vertical descent at the end of a call. The presence or absence of this structure can be important for distinguishing certain species. Eg, European Pied Flycatcher often has it whereas Spotted Flycatcher very rarely does.

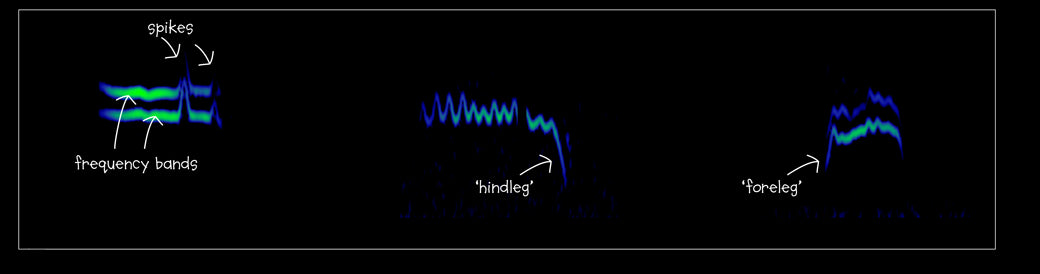

Concave

A curve which dips downward, i.e. it dips noticeably below the most direct line from its starting point to its ending point. For example, 1) a U-shaped line, 2) a descending curve that descends more rapidly at the start, then levels out, or 3) an ascending line that starts off rather flat then rises more sharply towards the end.

Convex

A line which arches upward, i.e., rises noticeably above the most direct line from its starting point to its ending point. For example, 1) a simple arch, 2) an ascending curve that ascends more steeply at the start, then levels out, or 3) a descending line that starts off rather flat then descends more sharply towards the end.

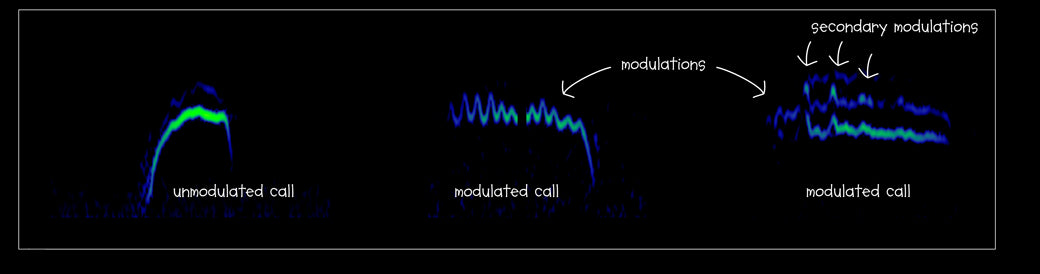

Modulations

The most generous definition of modulation in bird calls includes any change to the frequency or amplitude of a wave. However, here we use a narrower definition, referring to more or less regular oscillations in the frequency or amplitude, producing ‘zigzags’ (frequency modulation) or vertical hatching (amplitude modulation). Either way, the sound becomes harsher with rapid modulation than without it. Note that certain sonagram settings, such as window size or bandwidth have a strong influence on the appearance of modulations. At higher window size and smaller bandwidth values, fine modulations will disappear. If your Redwing Turdus iliacus calls show parallel bands instead of fine zigzag modulations, this is the reason.

Measurements

For some of the more difficult species, measurements on a sonagram will be one of the best ways to secure the identification. We make ours in Raven Pro, although there are several other applications that can be used for this.

Measurements of duration are fairly straightforward. The accuracy will be greater when the ‘window size’ of your sonagram is set to a lower value and you zoom in to make the call as big as possible on the screen. If your value seems to be on the low side, remember calls recorded at a distance may be missing details at the start or end of the call, making them appear shorter. Or the call you are measuring may simply have a duration at the shorter end of the range.

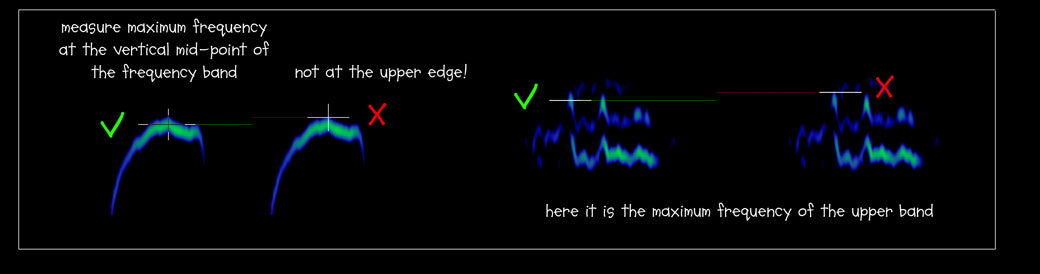

Measurements of frequency should always be taken at the vertical mid-point of the frequency band, at whatever point in time you are taking the measurement, even when you are measuring the maximum frequency. When measuring the top frequency of a rapid modulation, the bandwidth may be difficult to judge. In this case look at the width of the band in a less rapidly modulated part of the call and from this, estimate how far below the apparent peak of modulation you need to take your measurement.

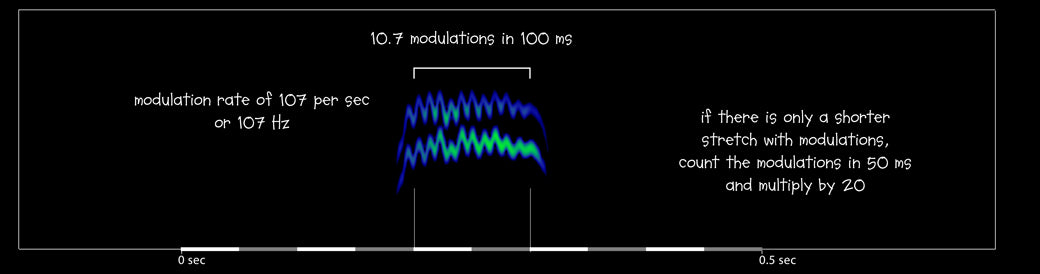

Modulation rate is the rate at which a sound oscillates up and down in frequency or in amplitude, typically producing what looks like vertical hatching in a sonagram (see definitions). Often the speed of this modulation is highly characteristic. Presumably it relates to the size or proportions of certain anatomical structures such as the bill and the vocal apparatus. Rates can be measured in Hz or oscillations per second, the same units used to express frequency (when expressing modulation rates, the values are much lower). In the case of nocturnal flight calls, most will be well under a second long, but we can measure a smaller part of the call and derive the rate per second from this. So, for example when measuring nocturnal flight calls of flycatchers, a 50 ms stretch can be multiplied by 20 or a 100 ms stretch by 10 to obtain a measurement in Hz. Even if the accuracy is not particularly high, this can be a helpful measurement.

The Sound Approach to Birding

The book that started it all, By Mark Constantine and The Sound Approach. No matter what your level of knowledge, with “The Sound Approach to Birding”, you will enhance your field skills and improve your standards of identification whilst listening to over 200 high quality sound recordings.