The Sound Approach

The world of bird sounds

High-quality recordings, award-winning publications and professional services

Welcome

Experts in bird sound identification, learning and media and commercial services

Welcome to The Sound Approach, the ultimate destination for bird enthusiasts, researchers and professionals. Whether you're a novice birder looking to identify your first species or an experienced professional seeking high-quality birdsong recordings, we have everything you need.

With decades of experience and a passion for birds, we offer an unparalleled archive of over 80,000 birdsong recordings, an extensive collection of award-winning books and expert media services for media production, research and more.

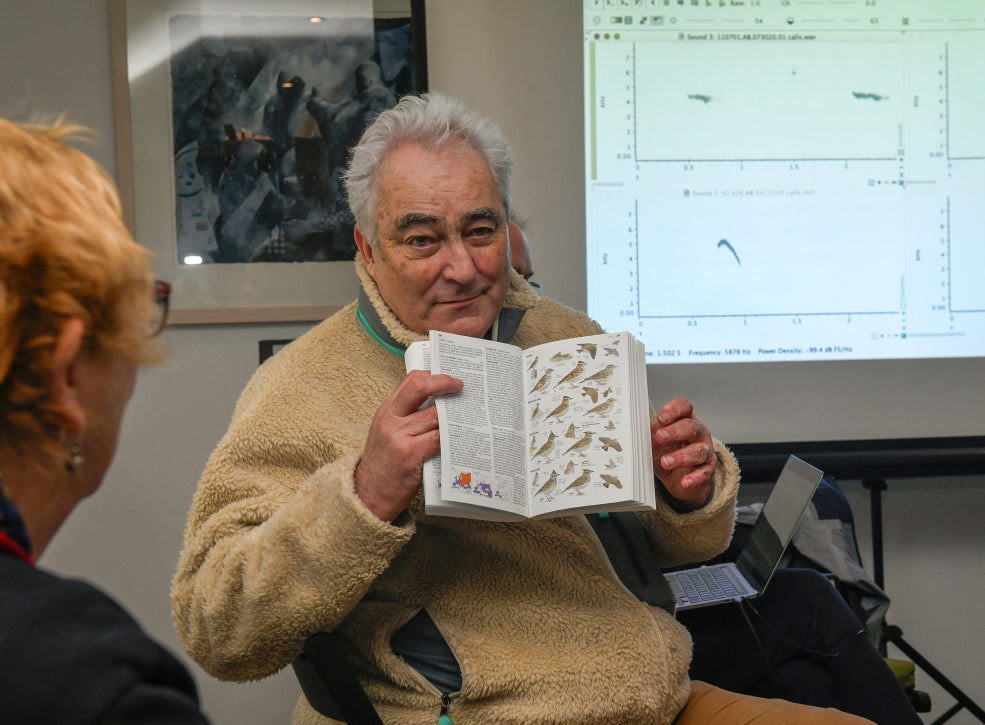

Our story

The Sound Approach is popularising birdsong and expanding our understanding of bird sounds. Whether you are a complete beginner starting your bird sound journey, are keen to expand your knowledge or want to delve into innovative research, we want to inspire birdwatchers to become bird listeners.

We own one of the largest private archives of bird sound recordings in the world, exceeding 83,000 recordings of more than 1,500 species, with a particular focus on the Western Palaearctic. We are an independent award-winning publishing house, with self-published books and multiple scientific papers.

-

High-quality bird sound recordings

Our archiveDive into our library of bird sounds. With over 80,000 bird sounds on file covering 1,500 species, our archive is one of most professional, high quality and extensive in the world. Each recording is accompanied by expert knowledge, allowing us to identify, age and sex hundreds of species, contribute to global bird science and make breakthroughs in bird identification.

-

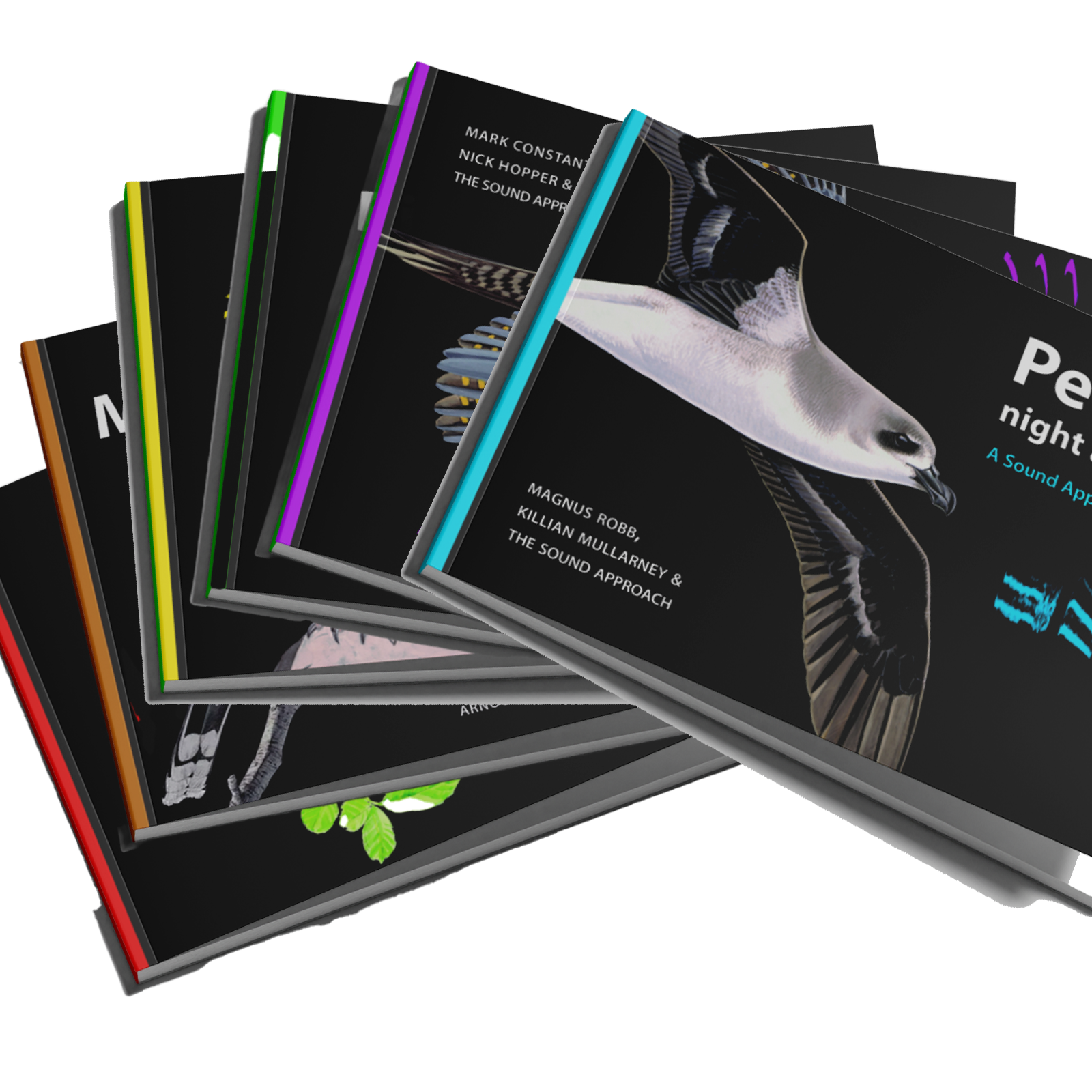

Comprehensive guides and books

Shop booksExplore our range of expertly written books, each dedicated to helping you identify and understand different bird species through their songs. Covering a range of species and geographical areas, our books are perfect for both bird sound beginners and seasoned birders.

-

Media and commercial sounds for productions

ConsultancyLeverage our expertise in birdsong for your next film, documentary, or audio project. Having worked with industry giants like the BBC and Netflix, we understand the nuances of capturing authentic soundscapes. And being birders ourselves, we can testify to the importance of accuracy when compiling your natural sound effects...

Our books

-

The Sound Approach to Birding (2006)

Regular price £24.95 GBPRegular priceUnit price / per -

Petrels: night and day (2008)

Regular price £29.95 GBPRegular priceUnit price / per -

Undiscovered Owls (2015)

Regular price £34.95 GBPRegular priceUnit price / per -

Birding from the Hip (2009)

Regular price £14.95 GBPRegular priceUnit price / per -

Catching the Bug (2012)

Regular price £29.95 GBPRegular priceUnit price / per -

Morocco: sharing the birds (2020)

Regular price £49.95 GBPRegular priceUnit price / per

In-depth recordings

Our recordings are meticulously gathered and analysed, allowing us to unlock the secrets of bird sounds around the world. This has allowed us to delve into unexplored areas of bird science. Below are some of the species we have worked on...

Expert services

We can turn our bird sound knowledge to a range of industries, from media productions and compiled soundtracks to renewable energy, ecological surveying and the wellbeing industries. Contact us to discuss opportunities.

-

Production

Use our bird sounds in your production

-

Creative

Partner with us in the creative arts

-

Work with us

Find out if our expertise can help you

-

Our archive

One of the highest-quality bird sound libraries in the world

The Sound Approach to Birding

The book that started it all, By Mark Constantine and The Sound Approach. No matter what your level of knowledge, with The Sound Approach to Birding you will enhance your field skills and improve your standards of identification whilst listening to over 200 high quality sound recordings.

Latest

-

Olive-backed Pipit - Separation from Tree Pipit

Magnus Robb

Ortolan Bunting - understanding their nocturnal migration calls

Magnus Robb, Nick Hopper, Paul Morton & The Sound Approach

Sicily, Italy

Magnus Robb

Mount Kazbegi, Georgia

Magnus Robb

Wadi Al Mughsayl, Oman

Magnus Robb

Masirah and Shannah, Oman

Magnus Robb

Homer Spit, Alaska, USA

Magnus Robb

‘Vedi Hills’, Armenia

Magnus Robb

Fuerteventura, Spain

Magnus Robb

Buuveit, Mongolia

Magnus Robb

‘Jalman Meadows’, Mongolia

Magnus Robb

Gun-Galuut, Mongolia

Magnus Robb

Raso, Cape Verde Islands

Magnus Robb

Seward Peninsula, Alaska

Magnus Robb

1 / of 25- Choosing a selection results in a full page refresh.

- Opens in a new window.

Little Grebe

Little Grebe

Common Quail

Common Quail

Black-crowned Night Heron

Black-crowned Night Heron

Black Redstart

Black Redstart

Eurasian Whimbrel

Eurasian Whimbrel

Little Bittern

Little Bittern

Common Sandpiper

Common Sandpiper

Spotted Crake

Spotted Crake

Common Blackbird

Common Blackbird

Common Greenshank

Common Greenshank

Green Sandpiper

Green Sandpiper

Common Redshank

Common Redshank

European Pied Flycatcher

European Pied Flycatcher

European Robin

European Robin

Meadow Pipit

Meadow Pipit

Wood Sandpiper

Wood Sandpiper

Bar-tailed Godwit

Bar-tailed Godwit

Redwing

Redwing

Ring Ouzel

Ring Ouzel

Eurasian Bittern

Eurasian Bittern