Killian Mullarney

Text by Magnus Robb.

On the way to Selvagem Grande, the largest of the Selvagens, we sailed towards a raft of thousands of Cory’s Shearwaters Calonectris borealis. They cleared a path, like a shoal of fish enveloping a shark. The closest ones took off at the very last moment, settling again on the outer edge of the raft. Gentle waves caressed the bows of our yacht. If the shearwaters had been calling we certainly would have heard them.

We went ashore at a cove called Enseada das Cagarras, named after the Cory’s Shearwaters. A smart field station and a small house belonging to the Zinos were the only buildings, sheltered from the north-east trade wind by steep rocky slopes. In the course of the afternoon, a few Cory’s started flying over the cove. By the time our skipper Luis Dias led us on a walk around the near side of the island, numbers were beginning to increase dramatically, and an almighty chorus was just starting.

Our walk took us on a winding path up behind the field station towards the plateau 100 m above sea level. On the way, we came to a saddle between our mooring and another cove to the east, named after Captain Kid, who is said to have hidden treasure there. Cory’s Shearwaters were making good use of the updrafts, sailing over the screes and cliffs, and some were flying exceptionally close. The scene was reminiscent of the Bosporus, Eilat or Gibraltar during the peak of migration, skies darkened by boiling ‘kettles’ of large soaring birds. But these were shearwaters! Nowhere else in the Western Palearctic do they visit their colonies in daylight.

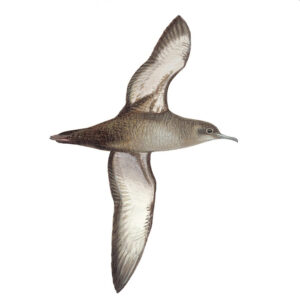

Cory’s Shearwater Calonectris borealis, Selvagem Grande, Selvagens 27 June 2006 (Killian Mullarney)

As you listen to the shearwaters’ calls in CD1-17, you will hear more males than females. Vocal sexing in Calonectris shearwaters was first demonstrated for Scopoli’s Shearwater C diomedea by Ristow & Wink (1979), although Lockley (1952) suspected differences when he heard Cory’s Shearwaters in the Selvagens as long ago as 1939. Across their entire repertoire, males always sound higher pitched, with a timbre reminiscent of a crying baby, while females sound deeper and more rasping, like a chain smoker with a terrible hangover. In CD1-17, the first bird that flies past (from centre to right) is a male, as are most of the closer shearwaters in the recording. Females can be heard much of the time in the background, coming to the fore from time to time. In CD1-18, which was recorded in the Azores, you can hear a female flying past at close range on her own.

CD1-17: Cory’s Shearwater Calonectris borealis ‘Captain Kid’s Cove’, Selvagem Grande, Selvagens, 19:00, 27 June 2006. Thousands flying over a large colony by daylight. The first one to fly past at close range (0:02-0:06) is the male shown in the sonagram. 06.008.MR.01626.01

CD1-18: Cory’s Shearwater Calonectris borealis Ilhéu da Vila, Santa Maria, Azores, 21:00, 12 April 2002. A female flying past at close range after dark. Background: Roseate Terns Sterna dougallii. 02.016.MR.02053.01

Selvagem Grande, Selvagens, in early evening, 27 June 2006 (Luis Dias). This is where CD1-17 was recorded.

Sexual differences in Cory’s Shearwater vocalisations are quite extreme. The rasping quality of the female’s voice is caused by the sound becoming loud and quiet nearly 100 times a second, which is called amplitude modulation. When you take a rapidly pulsing sound and speed it up, the perception of individual pulses begins to disappear, and the sound takes on a rasping quality. Speed it up some more and the rasping changes into a smooth hum. The number of pulses per second becomes the fundamental frequency of this humming sound. Female Cory’s have a sound more or less on the borderline between a rasping sound and a deep hum, and sonagrams can show either quality, depending on how you tweak the settings.

In Selvagens females, Bretagnolle & Lequette (1990) found that the fundamental frequency averaged 84 Hz, four times lower than the 367 Hz of males. Male Cory’s Shearwaters have regular frequency bands or harmonics which move up and down ‘in harmony’. In females, the pattern of frequency bands is more irregular and confused, with some moving up at the same time as others are moving down. I believe this is because they also produce a second, weaker sound at the same time, with a fundamental frequency not dissimilar to the male’s. This interferes with the lower fundamental, causing the irregularity that can be seen in sonagrams.

Cory’s Shearwater Calonectris borealis, calling male, Praia, Graciosa, Azores, 28 May 2007 (Killian Mullarney)

When male and female Cory’s Shearwaters are calling together in their burrows, their communication is often rather informally structured and you will hear, for example, a less regular rhythmic pattern. But at all times, it is easy to tell male and female apart. In CD1-19, you can hear a conversation between neighbouring pairs. A female rasps at the start and her mate whines twice ‘in agreement’. Then the male of a second pair cries from 0:11, being joined by his mate from 0:15.

Male and female Cory’s Shearwaters are able to tell each other’s calls apart, and both sexes are able to recognise their own mate, although it is not known whether they recognise the calls of their nearest neighbours (Bretagnolle & Lequette 1990).

Cory’s Shearwaters of either sex are about twice as likely to respond to calls of a same sex rival as to their mate. Breeding males appear to be impeccably well behaved: they answer calls from their own mate, but hardly ever respond to other females. They are thought to be highly faithful to their partners: two studies of Calonectris shearwaters have failed to find evidence of ‘illegitimate’ offspring (Rabouam et al 2000, Swatschek et al 1994). In this light, it is unclear why females respond strongly to the calls of other females. Are the males really so impeccably behaved, or is the lack of illegitimate offspring due to females successfully defending their mate from the amorous advances of rivals?

CD1-19: Cory’s Shearwater Calonectris borealis Farilhão Grande, Berlengas, Portugal, 23 September 2003. Two pairs answering each other under the foundations of an unmanned lighthouse. Background: Grant’s Storm Petrel. 03.036.MR.14300.00

Unmated Cory’s Shearwaters have very different priorities. Males that have already secured a burrow will call both from the ground and in the air to attract flying, non-breeding females. If an unmated female is interested she may then call in response. Should one thing lead to another, a different call may eventually be heard. Copulation calls are produced only by the male, and consist of a series of short, paired notes in a rhythm like a galloping horse (CD1-20).

CD1-20: Cory’s Shearwater Calonectris borealis Ilhéu da Vila, Santa Maria, Azores, 12 April 2002. Copulation calls of a male. Background: Barolo Shearwater Puffinus baroli. 02.016.MR.04640.00

The Berlengas, just 90 km from Lisbon, Portugal, are a small archipelago where north and south struggle for control, and south seems to be winning. Not so long ago, Europe’s most southerly Common Murres Uria aalge could be found here; Lockley estimated about 6000 pairs when he visited in 1939, but they have not bred since 2002 (Lecoq 2002). On the other hand, warm water seabirds like Yellow-legged Gulls Larus michahellis and band-rumped storm petrels Oceanodroma are thriving. I visited the islands to record the storm petrels in September 2003. During a bumpy zodiac ride from the fishing port of Peniche, I saw good numbers of Cory’s Shearwaters, as well as the occasional Sooty Shearwater Puffinus griseus heading for its southern hemisphere breeding grounds. When we passed a small Ocean Sunfish Mola mola, it jumped clean out of the water.

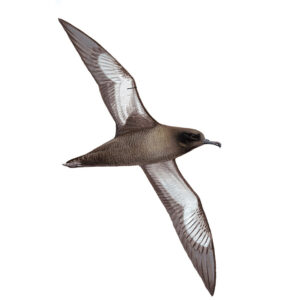

Cory’s Shearwater Calonectris borealis, near the Selvagens, 26 June 2006 (Killian Mullarney)

Just over a hundred pairs of Cory’s Shearwaters breed on the main island (Lecoq 2002), where there is a fishermen’s village and a manned lighthouse. A smaller colony is located on the outlying Farilhões, a few uninhabited and rat-free islets. In the Berlengas, hatching takes place around 25 July (Granadeiro 1991), so the nestling in CD1-21 would have been c 60 days old. I found it on Farilhão Grande, under the foundations of the lighthouse. You can hear its high-pitched, vibrant ‘long begging calls’ at the start, before a neighbouring pair buts in loudly at 0:14, and a female calls as she flies past on the left (0:22-0:29). Towards the end, you can hear the nestling again, calling more rapidly, as if to compensate for the interruptions.

CD1-21: Cory’s Shearwater Calonectris borealis Farilhão Grande, Berlengas, Portugal, 23 September 2003. Long begging calls of a nestling, and calls of a pair of adults under the foundations of a lighthouse. A female flies past on the left. Background: Grant’s Storm Petrel 03.036.MR.14141.00

Before they have reached the age of c 80 days old, young Cory’s Shearwaters have two calls they use for begging. The ‘long begging call’ is the one more often heard, especially when a parent is present, but it can also betray the location of a solitary, hungry nestling. The ‘rhythmic call’ is used very little by Cory’s, only seeming to initiate feeding sessions and to serve as a contact call with parents. After they are 80 days old, nestlings develop adult-type calls, making it possible to tell males and females apart before they leave the nest (Bretagnolle & Thibault 1995).

In a series of experiments on the Berlengas, Quillfeldt & Masello (2004) showed that young Cory’s Shearwaters convey honest information about how hungry they are to their parents, who vary their feeding accordingly. Nestlings that had been given feeding supplements begged less intensely when their parents arrived. Their parents took note, and the next feed was smaller and usually followed after a longer gap. These experiments took place in 2002, a year when the seas along the Portuguese coast were highly productive. Similar experiments in the Selvagens during the less productive year 1998 revealed a different picture (Granadeiro et al 2000). Nestlings in poor condition were unable to increase their rate of begging beyond a maximum of about 1.2 calls per second, which possibly gave them just enough time to swallow regurgitated food between calls. But more intense calling might not have helped them anyway. When food is scarce, parents are probably not able to supply more food, even if the nestlings are able to demand it.

Cory’s Shearwater Calonectris borealis, near the Desertas, Madeira, 30 June 2006 (Killian Mullarney)

In the not so distant past, nestling Cory’s Shearwaters in the Selvagens were themselves food for the people of Madeira. Just as ‘gugas’ or young Northern Gannets Morus bassanus are annually harvested on the Scottish island of Sula Sgeir, young ‘cagarras’ were a treat for the people who lived on Madeira and other Macaronesian islands. Fishermen scoured the Desertas in early autumn, and in the early 20th century, 7000 young Cory’s were killed there each year (Schmidt 1907). In the Selvagens, the slaughter took place on an industrial scale: “there was apparently rigid control of the Cagarras. We were told that the adults were never molested, but only the fledglings killed – at the stage when they are about to be, or are, deserted by the parents. The cagarra-farm of Great Salvage was said to yield between ten and twenty thousand fledglings each September; these were cleaned and preserved with salt, for sale in Madeira” (Lockley 1952, on the situation in 1939).

A detailed history of the annual slaughter by Alec Zino (1985) confirms that approximately 22 000 shearwaters were harvested in about three weeks. Besides eating the meat from these birds, the Madeirans sold their feathers to be used as ‘eiderdown’ in England, and the fat was melted down to be used as bait. When Zino witnessed the harvest on Selvagem Grande for himself in 1963, he was outraged. Within a few years, he bought the hunting rights to the islands, but this was not the end of the story.

“To promote further studies of the birds on the islands he built a house on Selvagem Grande in 1967 and, typical of his kindness, employed many of the fishermen, now relieved of their hunting rights, to help construct the building. In 1971 he organized the sale of the islands to the WWF, but the Portuguese Government forbade the sale and bought the islands themselves, but failed to warden them. In 1974 there was a revolution in Portugal and in 1976 the same fishermen, inspired by the military coup and general lawlessness on the islands, sought revenge for the loss of their ‘tradition’ by slaughtering almost every bird they could find and completely ‘trashed’ the Zino house. The publicity derived from this appalling vandalism persuaded the local and national government of Portugal to take a more active role in wildlife protection. With Portugal’s later membership of the EC, all wildlife directives were readily embraced and the islands quickly gained National Park status with the founding of the Parque Natural da Madeira in 1986” (Zonfrillo 2004).

Since the slaughter of 1976, the population on Selvagem Grande has been able to recover (at 6.7% increase per year; Mougin et al 1996), but numbers are still well below previous levels. In 2000, the combined population of Madeira, the Desertas and the Selvagens was estimated at 16 500-25 000 (BirdLife International 2004). This sounds like a lot, but in the past this many fledglings were killed each year on Selvagem Grande alone (Zino 1985).

The most important stronghold for Cory’s Shearwater is the Azores, where about 188 000 pairs were estimated to breed in the late 1990s. Until recently, their breeding range was thought to be restricted to the Atlantic, while the very similar Scopoli’s Shearwater replaced Cory’s in the Mediterranean. However, a single colony of Cory’s has been discovered on the Terreros islands in Almeria, Spain. These are situated in the Alboran Sea, the westernmost part of the Mediterranean, which is oceanographically similar to the Atlantic (Gómez-Díaz 2006).

Throughout the breeding range, from the Azores to the Alboran Sea, and from the Berlengas to the Canary Islands, calls of Cory’s Shearwaters sound very much the same. What varies from place to place is the character of a colony as a whole: how many pairs it holds, and whether wind, sea, or features of the landscape affect the prevalent acoustics.

Cory’s Shearwater Calonectris borealis: known breeding distribution (red dots). Recording locations indicated by arrows (north to south):

Farilhão Grande, Berlengas, Portugal;

Ilhéu da Vila, Santa Maria, Azores;

Selvagem Grande, Selvagens;

Barranco del Infierno, Tenerife, Canary Islands.

My first encounter with Cory’s Shearwaters, back in April 2001, was in the Barranco del Infierno on Tenerife in the Canary Islands. I entered this spectacular ‘gorge of hell’ an hour before sunset. The wonderful acoustics of the gorge encouraged late walkers to play with their echoes as they hurried back out, returning to busy resorts before the darkness poured in. Perched on a prominent rock, I listened to the gradual change from day to night. A patchy covering of scrub clung to the arid, crumbling slopes of the gorge. On the other side, a calling Barbary Partridge Alectoris barbara found just enough cover to remain unseen.

The first few Cory’s Shearwaters to call, hidden inside distant burrows, were so muffled I failed to recognise them. When the night shift began to arrive from the sea, and shearwaters took the place of the tourists, the gorge resounded like a cathedral. Arriving birds could be heard circling around a few times, flying close to the ground as they passed their burrows, then landing with a thump on the final approach. Judging by the loud duets coming from all sides, many of them found their mates waiting in their burrows. I was thrilled by the loudness of some calls coming from under a rock just a few metres away. Deafeningly loud or muffled and distant, there was no longer a second without a call or an echo of a Cory’s.

Since that time, I have visited many other colonies. The sound is always impressive, but for me, the fantastic sound of the Barranco del Infierno has never been surpassed. It is not difficult to understand how the gorge got its name.

CD1-22: Cory’s Shearwater Calonectris borealis Barranco del Infierno, Tenerife, Canary Islands, 8 April 2001. Individuals calling as they fly around in a narrow canyon a couple of hours after sunset. 01.009.MR.01606a.00