Killian Mullarney

Text by Magnus Robb.

Diomedes, one of the heroes of the siege of Troy, is commemorated in the scientific name Calonectris diomedea, chosen by Giovanni Antonio Scopoli for his new shearwater back in 1769. According to myth, when Diomedes died, his fellow warriors were inconsolable, and they metamorphosed into birds (Marchant & Higgins 1990). Scopoli himself was an Italian-Austrian doctor and naturalist, the son of a lawyer. Besides his shearwater, and the many plant and insect species he described, Scopoli is also remembered for investigating the symptoms of mercury poisoning among miners.

Charles Barney Cory, perhaps surprisingly, was an American. The type specimen of Cory’s Shearwater was killed near Cape Cod, Massachusetts, USA, on 11 October 1880. When Cory saw it, he showed it to some fishermen and asked them to procure any others they might encounter. The same afternoon they returned with more, having found a flock a short distance offshore (Cory 1881). For speakers of Danish and Dutch, the ornithologist associated with this species is not Cory, but Heinrich Kühl, and indeed Puffinus kuhli used to be its scientific name. A German born ornithologist who was assistant to Temminck at Leiden museum in the Netherlands, Kühl is also remembered for writing the first monograph on the petrels (1820), and he still has a pipistrelle bat named after him.

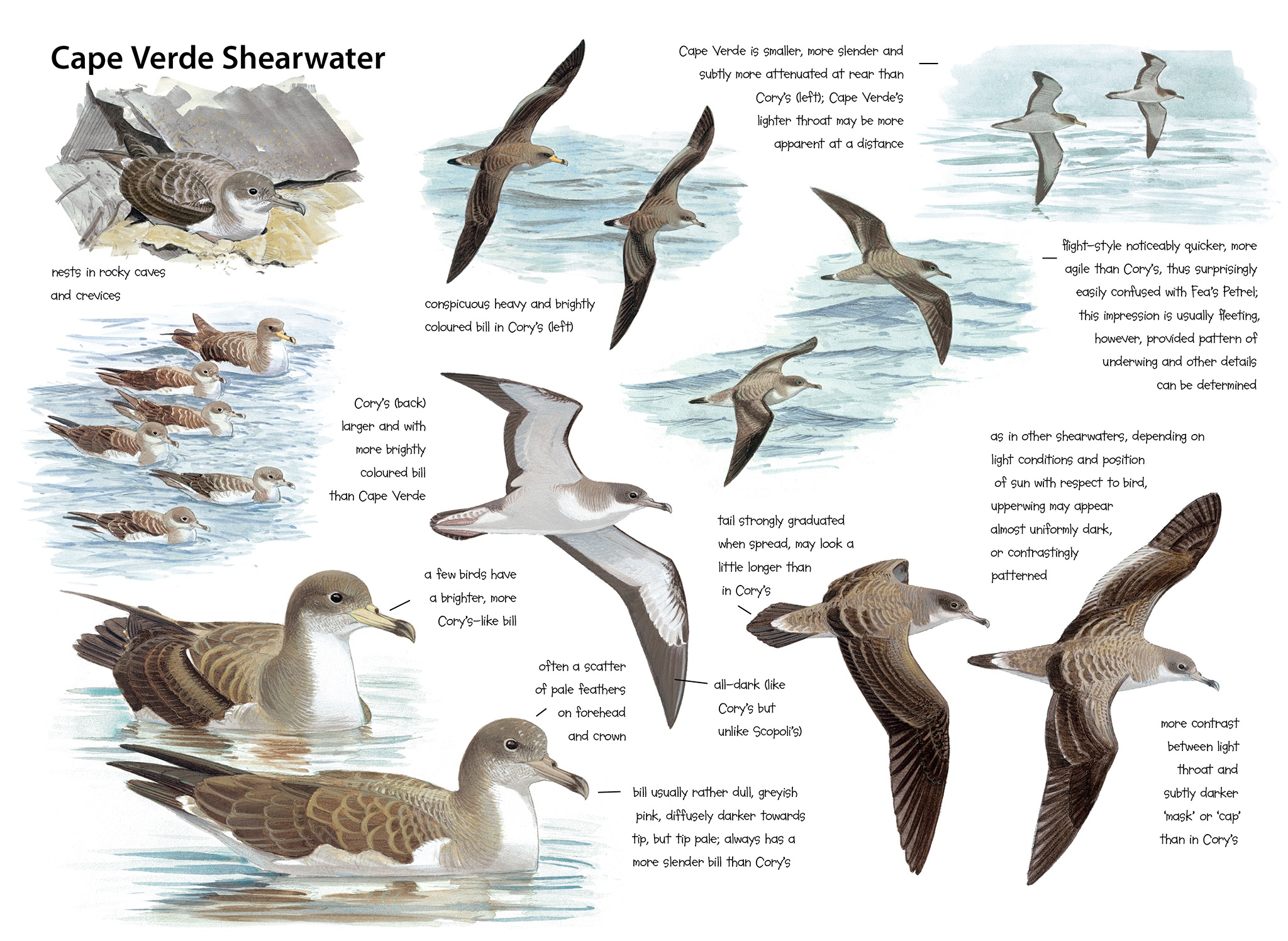

In 1883, the French ‘Talisman’ expedition, led by Alphonse Milne-Edwards, was investigating the marine biology of the Atlantic. They visited Cape Verde seas in July, making a landing on the islet of Branco. Among the birds collected there was a new shearwater, which Émile Oustalet later named Puffinus edwardsii after Milne-Edwards, who was professor of ornithol-ogy at the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris, France. After the Talisman expedition, the Cape Verde Shearwater was almost immediately forgotten. Such was the neglect that Boyd Alexander, on a visit to the Cape Verde island of Brava in 1898, ‘discovered’ it again, naming it P mariae (Alexander 1898). Ironically, this British ornithologist is now remembered for collecting the first specimens of another Cape Verde species, Boyd’s Shearwater P boydi, which was not described until after he died. Then, as now, the chief strongholds of Cape Verde Shearwater were the uninhabited islets of Raso and Branco, situated among the Barlovento or windward islands in the north-west of the Cape Verde Islands. I have survived two visits to these islets, and the accompanying recordings of Cape Verde Shearwater were all made on Raso.

Cape Verde Shearwater Calonectris edwardsii, São Nicolau, Cape Verde Islands, 25 March 2007 (René Pop)

At Tarrafal harbour on São Nicolau on 13 February 2004, both Arnoud and I were a little apprehensive when we saw the tiny blue boat that was to take us across 13 nautical miles of sea to Raso. We had seen photographs of boats used by birders before, and they looked big enough to carry a football team. Our boat was not only very small, but also appeared to be falling apart. It had not been painted in years, had no radio or emergency equipment, was leaking, and produced an awful lot of fumes. Arnoud is not a great sailor, but when he got on board he was still in good spirits, assuming the little blue boat was just to bring us to a larger one moored out in the bay. No such luck! As soon as we had left the wind shadow of São Nicolau’s mountains, the sea became very rough.

“We are in mortal danger, heading for Raso in an unseaworthy vessel” was the jist of the emergency text message he sent to Mark Constantine, thinking it might be his last. Standing in the cabin door, hanging on one arm, he closed his eyes and switched off his brain as best he could. The sight was enough to make me, a fairly good sailor, feel a bit queasy too. Every now and then I did have to wake him from his torpor. “Arnoud, Fea’s Petrel!…” or “Arnoud, Red-billed Tropicbird!…”. Then he would open his eyes, focus his bins, politely thank me, then return to the land of ‘Noud. Only once did I have the occasion to wake him with “Arnoud, Cape Verde Shearwater!”. It was the only one we saw during the entire trip.

Cape Verde Shearwater Calonectris edwardsii, Raso, Cape Verde Islands, 24 March 2007 (René Pop)

From late November to the second half of February, Cape Verde Shearwaters are absent from the seas around the archipelago. Where they go at this time is still poorly known. At the end of the breeding season, large numbers have been recorded off Senegal, the nearest country on the African continent (Porter et al 1997). Several have been found along the south Brazilian coast (Petry et al 2000), and on 18 February 1992, three were observed as far south as Argentina (Curtis 1994).

In March 2007, I set off for Raso again, this time with the specific goal of recording Cape Verde Shearwaters. Even before Killian, René Pop, Pim Wolf and I left the harbour of Tarrafal it was clear that there would be no shortage of shearwaters this time. Not far offshore, we could see them feeding on scraps discarded by local fishermen. I was more than a little surprised to see that our little blue boat from 2004 was still afloat, tied up at the pier. This time we had hired the Genizé, a larger, more stable vessel, and Killian and I wore life jackets bought specially for the occasion. For me this was by far the safest fishing vessel I had ever sailed with in Cape Verde seas. Nevertheless, as Killian remarked, a health and safety officer would have had a field day.

Cape Verde Shearwaters Calonectris edwardsii, between São Nicolau and Raso, Cape Verde Islands, 20 March 2007 (Pim Wolf)

On the way across, we saw hundreds of Cape Verde Shearwaters, some passing at incredibly close range. By the time we reached Raso, René Pop was grinning like a madman. He had longed to photograph the shearwaters ever since his last visit to the islands, 21 years previously. We landed on the leeward south side, at a point where we could climb the low cliffs quite easily. To save us lugging our gear any further, we set up camp right under the cliffs. Unusually for Raso, it looked like there might be rain, so we moved into a small cave. It was not long before we realised it was already occupied. From deep in the furthest recesses, faint growls of Cape Verde Shearwaters could be heard, muffled by the rocks. Then we noticed a Red-billed Tropicbird Phaethon aethereus that kept flying up to the entrance but veering off at the last minute. We moved to an alternative spot nearby, under an overhanging section of cliff, where we hoped to cause less disruption.

Magnus Robb, René Pop and Killian Mullarney (from left to right) at their ‘hotel’ on Raso, Cape Verde Islands (Pim Wolf)

In March, nearly all of the Cape Verde Shearwaters at the colony will be adults. Pair bonds have been formed in previous years, and the priority at this time is to defend the burrow from newly formed pairs who might try to steal it, especially at dawn or dusk. This explains why many birds stay in their nests by day, although it will be another couple of months before they lay and incubate their egg. At night, most vocal activity seems to involve interactions between pairs. Males and females sing loosely co-ordinated duets, responding to other duets, as well as to callers in the air. In CD1-28, you can hear a typical March soundscape from one of the rockier parts of Raso at night. The microphone was nestled among some boulders during the peak of the evening chorus.

CD1-28: Cape Verde Shearwater Calonectris edwardsii Raso, Cape Verde Islands, 20:31, 21 March 2007. Calls of males and females in the early part of the night. Some are calling in flight, and one female passes particularly close a number of times (eg, 0:05-0:15, 0:49-0:56, 1:01-1:07, 1:14-1:22 & 1:27-1:34), sometimes eliciting vigorous responses from nearby pairs on the ground. 070321.MR.203132.01

When you listen to these Cape Verde Shearwaters, you can hear that they are closely related to Cory’s, and particularly Scopoli’s Shearwaters. The greater similarity to Scopoli’s is due to the fact that Cape Verde generally also has two exhaled notes, rather than the three of Cory’s. Not surprisingly for a smaller bird, the pitch of Cape Verde calls is higher, and this also means that they have a slightly different tonal quality. The inhaled notes of male Cape Verde are so high-pitched they almost sound whistled. Females also to show a marked difference between their inhaled and exhaled notes. The effect of these strong contrasts (male and female as well as inhaled and exhaled notes) can be rather confusing, even suggesting that four different types of shearwater are present at once. However, by listening to the sexes one by one, it becomes easier to separate out individuals from the cacophony.

CD1-29: Cape Verde Shearwater Calonectris edwardsii Raso, Cape Verde Islands, 20:52, 21 March 2007. A male calls in flight and is answered by at least four birds on the ground. 070321.MR.205246.01

CD1-30: Cape Verde Shearwater Calonectris edwardsii Raso, Cape Verde Islands, 19:43, 22 March 2007. A female calls in flight and is answered by several birds on the ground. 070322.MR.194313.01

In CD1-29, you can hear the start of a chorus I recorded one particular evening on a hill in the western part of Raso. A Cape Verde Shearwater had been flying excitedly back and forth in the dark without calling, but I could follow it easily thanks to the sound of its wings. When it emitted some high, whining calls, announcing that it was a male, the tension immediately broke, and as you can hear, at least four birds responded at once. In contrast to Cory’s Shearwater, every exhaled note is followed by a clearly audible inhaled one at a much higher pitch. This is a character Cape Verde shares with Scopoli’s Shearwater although the latter has lower pitched calls. The high pitch and whistle-like quality of these inhaled notes of the male are the most distinctive vocal characters separating Cape Verde from Scopoli’s Shearwater. Separation from Cory’s Shearwater is easier, because Cory’s usually has three much shorter exhaled notes, and its calls are much lower in pitch. Now listen to a female calling in flight and eliciting a very similar response from two or more pairs on the ground (CD1-30). As in males, the first exhaled note is followed by a short breath note, and the second exhaled note is followed by a longer breath note.

Cape Verde Shearwaters Calonectris edwardsii, calling at night, Raso, Cape Verde Islands, 21 March 2007 (René Pop)

One evening on Raso, René and I went to the north-east of the island. We found a valley leading down to the coast, with a tiny ravine down the middle. It was only a few metres across, but lined with typical Cape Verde Shearwater nests on both sides. Each had a little doormat consisting of rounded pebbles of a certain size, neatly arranged around the entrance and sprayed with droppings. Just over half an hour after sunset, the shearwaters inside started to call much more loudly than they had done in the daytime, perhaps moving closer to the entrance to project their sound further. When the first birds arrived from the sea, they flew in without calling, landed with a crash and ran straight up over the pebble doormat before disappearing into their nests. Often it seemed that a single entrance cavity and doormat actually belonged to more than one pair. In CD1-31, you can hear three different birds arriving and shuffling up to their burrows (the first at 0:09), followed by a less than warm welcome from their neighbours.

CD1-31: Cape Verde Shearwater Calonectris edwardsii Raso, Cape Verde Islands, 19:27, 20 March 2007. Three birds arrive from the sea in close succession, provoking duets from pairs already in their burrows. 070320.MR.192736.01

Fights are not uncommon in the early part of the breeding season, and we saw several birds with bloodied heads. I can speak from experience when I say that the Cape Verde Shearwater has a razor sharp bill. In CD1-32, you can hear a fight involving a female. More than likely, the other combatant was a female too, as aggression in petrels is usually between members of the same sex. Although higher and lower notes can be heard, these are probably inhaled and exhaled notes of the same bird. Aggressive calls in all shearwaters tend to be rather monosyllabic and Calonectris is certainly no exception.

CD1-32: Cape Verde Shearwater Calonectris edwardsii Raso, Cape Verde Islands, 22:27, 20 March 2007. Two birds fighting; the one calling is a female. The higher notes are inhaled and the lower ones exhaled. 070320.MR.222705.01

Cape Verde Shearwater Calonectris edwardsii, between São Nicolau and Raso, Cape Verde Islands, (René Pop)

These fighting shearwaters were using calls similar to ones we heard at sea. On the way back to São Nicolau, we stopped to observe some that were feeding on discarded fish remains (CD1-33). While fighting over these morsels, they typically held their wings high, pushed out their breast and held back their head in defence. They often cocked their tail too, like a poorly endowed peacock. When they were ready, they all took off in the same way. Holding their wings level to the surface, they faced into the wind and ran as fast as they could, only flapping their wings when they were well clear of the water.

Cape Verde Shearwaters Calonectris edwardsii, fed fish scraps by fishermen, São Nicolau, Cape Verde Islands, 20 March 2007 (Pim Wolf). This scene can be heard in CD1-33. Raso and part of Branco can be seen in background.

Cape Verde Shearwaters Calonectris edwardsii, squabbling over fish scraps, São Nicolau, Cape Verde Islands, 25 March 2007 (René Pop)

Calls of Cape Verde Shearwaters at sea have been remarked on several times in the literature, so perhaps Cape Verde are more vocal offshore than other species. Murphy (1924) observed that they do some of their courting at sea. “They rest on the water in large concentrations, sometimes forming rafts of birds a hundred feet square, and at such times the love-making goes on with much caressing of bills and necks. During the amorous pursuits of one bird after another, conflicts take place which often involve more than the single pair. Sometimes I saw regular battles between groups of the birds”.

When reading and researching the background to a book like this, you sometimes stumble across opinions so different from your own that they take your breath away. Onley & Scofield (2007) managed to do this, in Albatrosses, petrels and shearwaters of the world, when they wrote: “in our experience, voice is not useful in the separation of any species of albatross or petrel.” If you have read and listened this far, you will understand why this brought a smile to my face. Even within the context of observations at sea, sounds are well worth listening for. As the sonagram of CD1-33 shows, Cape Verde Shearwaters can be sexed at sea by differences between their calls.

CD1-33: Cape Verde Shearwater Calonectris edwardsii São Nicolau, Cape Verde Islands, 22:27, 25 March 2007. Males and females fighting over scraps discarded by fishermen. 070325.MR.111702.01 & 070325.MR.111815.01

Most species of shearwaters call at sea, so there is plenty more scope for vocal sexing. I have heard male and female Cory’s Shearwaters in the afternoon, waiting to come ashore on Ilhéu do Farol, Madeira. They can be just as vocal as Cape Verde Shearwaters, but I have also encountered rafts that were completely silent. Two Boyd’s Shearwaters P boydi together off São Nicolau could be heard giving some gruff calls, but disappeared before I could record them (they sounded like females). I have also heard male and female Balearic Shearwaters courting at sea a few hundred metres distant from a colony. This began at dusk, before the colony itself came to life, and continued throughout a calm March night. Similar behaviour has been recorded in Manx Shearwater P puffinus chasing, displaying and calling below cliffs at Fetlar, Shetland (Tulloch 1977). In Ireland, Anthony McGeehan has occasionally heard Manx calling about 5 km from breeding colonies, at least two hours before sunset.

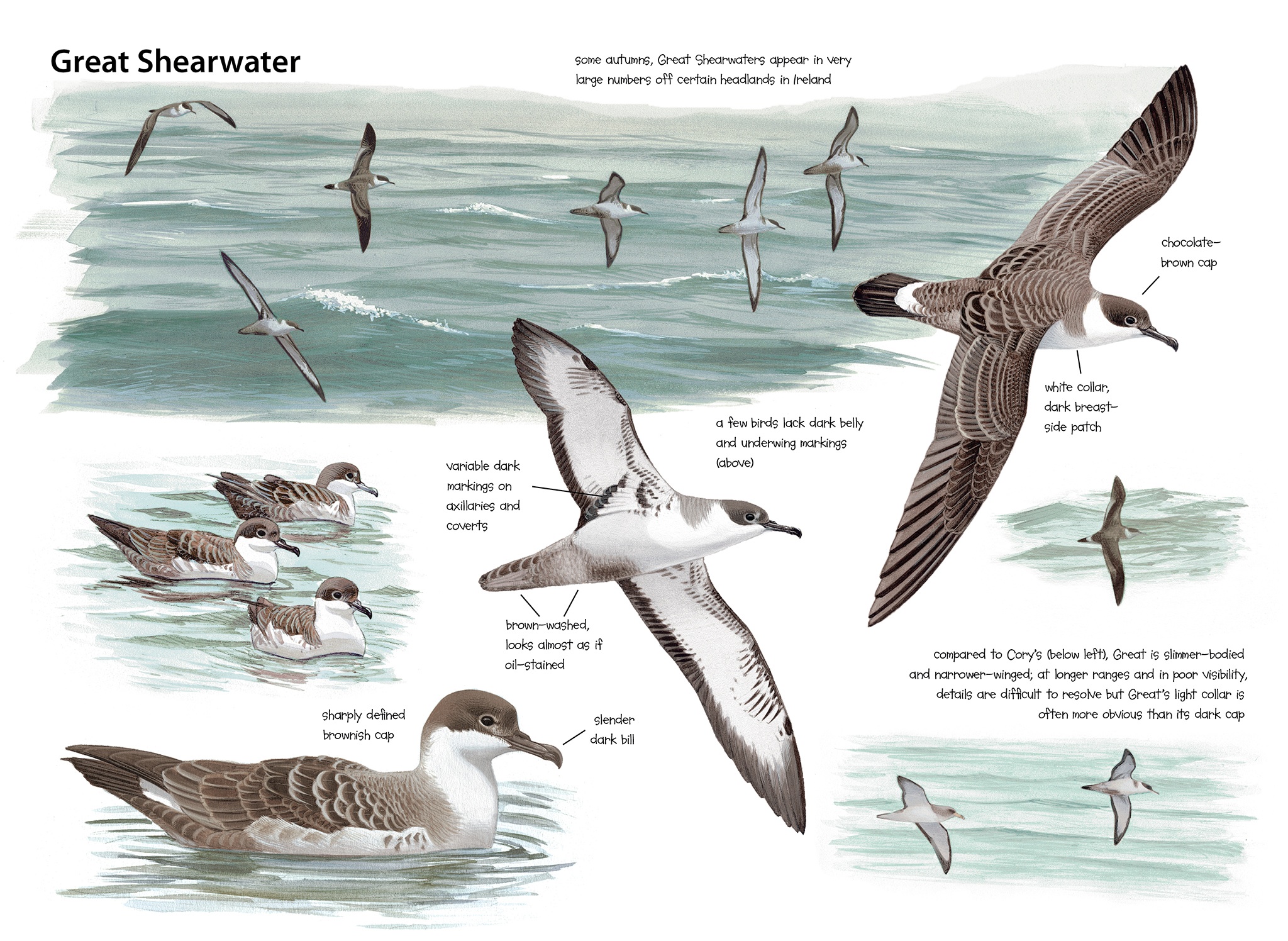

There are two species whose voices can be heard only at sea in the North Atlantic, because their breeding colonies are south of the equator. “Raucous calls and screams” of Sooty Shearwaters P griseus at sea have been noted by Palmer (1962). But perhaps the most vocal of all shearwaters at sea is Great Shearwater P gravis, which breeds mainly in the Tristan da Cunha archipelago in the South Atlantic. At one time, this was the only shearwater in the European field guides that I had never seen. Finally, in August 2006, I saw over 30 while seawatching from Skellig Michael, Kerry. A couple of days later, Mark forwarded me a text message from Anthony McGeehan, who had seen a whole raft of them off Donegal, Ireland, and even heard them calling! The recording in CD1-34 was captured using a video camera by Stuart McKee, who was with Anthony that day.

CD1-34: Great Shearwater Puffinus gravis near Tory Island, Donegal, Ireland, 27 August 2006. Calls coming from a raft of about 100 Great and two Sooty Shearwaters P griseus, recorded on a rough day by Stuart McKee.

Anthony later described the behaviour of these Great Shearwaters for me:

“The birds’ body language was curious. Rather than growing uneasy as we wallowed towards them, they looked content. Each faced into the wind, head down. Their demeanour suggested a group of roosting shorebirds. Surely they must fly, if we get any closer they will have to swim to get out of the way? Actually, some did rise off the water, only to resettle on the far flank of the flock. Their group organisation was intense and reinforced by an outburst of calling. Picture and now sound. The rocking of the boat did not feel so bad any more. The birds and us seemed to share a kind of unison. At times, we rose and fell in harmony. Never having read a word about Great Shearwater vocalisations, I had no idea what to expect. What we heard was not so much individual calls, it was a chorus. Northern Fulmar is comparable in size to Great Shearwater and its gruff and guttural tones might have served as a basis for analogy. Wrong. Compared to Northern Fulmar, these birds were Nightingales. ‘Like Kittiwakes on helium’ was a pretty good handle. High and mewing: a cartoonish, baby voice that did not fit the bird yet was completely endearing.

Killian Mullarney

Independent of anything that we did, the calling stopped. Like a glider squadron lining up for a phased take off, small parties taxied into flight but wheeled around the core of the flock until those birds too became airborne. There was no rush, no panic. A muted ballet culminated in a great circling spiral of shearwaters. Only then did they go. We knew that was it. The performance was over. It was still early on a Sunday morning and it felt like a church service had just been enacted. Maybe something from the Book of Revelations. A lesson confirming humankind’s place in evolution: above rodents, below seabirds.”

Great Shearwaters Puffinus gravis, Tory Island, Donegal, Ireland, 27 August 2006 (Anthony McGeehan). The same birds as in CD1-34.

The sea was very rough that day, and it must have been difficult for Stuart to make the recording. Holding on for dear life, trying not to let a prized video camera fall into the sea, while trying to keep it steady enough to film at the same time. By comparison, the Cape Verde Shearwaters off São Nicolau were relatively straightforward to record. In the lee of São Nicolau, I could even stand up straight without holding on, and apart from slight engine noise and a few camera clicks, the only extraneous sound was a fisherman singing a little song about ‘cagarras’, the Portuguese and Creole name for a Calonectris shearwater.

In September each year, this idyllic scene is turned completely on its head. Instead of cagarras foraging for scraps around fishing boats, fishermen arrive on the island of Raso to harvest the young shearwaters. Most come from the southernmost village on the island of Santo Antão. On that island, cagarras are considered a great delicacy, and people get very excited when you mention them.

Cape Verde Shearwater Calonectris edwardsii.

Recording locations indicated by arrow: Raso & São Nicolau, Cape Verde Islands.

Cape Verde Shearwaters appear to have been living on Raso and Branco for a very long time, to judge from some of the guano deposits that have accumulated there. Outside a large crevice above our base camp, there was a smoothly sloping white landing ramp we named the ‘shit glacier’. This unmistakeable landmark actually helped us find our way back in the dark. Cape Verde breed in smaller numbers on one or two other islands, but have disappeared from several more. Santa Luzia, the larger island west of Branco, has plenty of suitable habitat and must have been an important breeding site before the archipelago was colonised by humans. Whalers arrived there first, introducing rats and mice, and families settled later, bringing goats, cats and other domestic animals. The sparse vegetation was finished off by the goats, and Santa Luzia was abandoned, but not before the demise of its seabirds (Hazevoet 1994). Now there are none breeding there at all, and it must be a very sad place indeed.

Raso seems to have sustained the ‘cagarra’ harvest for a long time, but it is doubtful how much longer it can manage. The total population of Cape Verde Shearwaters has been estimated at only about 10 000 pairs, but about 5000 young are taken from their nests each year (Nunes & Hazevoet 2001). So perhaps we should be grateful for its inaccessibility, and the ramshackle state of Cape Verde’s fishing boats.

In 1990, Cornelis Hazevoet was instrumental in securing Nature Reserve status for Raso, Branco and a number of other islets. Despite this, the shearwater harvest on Raso has continued as before. Hazevoet has continued ringing the alarm bells, along with Manuela Nunes of SPEA, the BirdLife partner in Portugal, and luckily, I am able to end this chapter on a positive note. While visiting Santo Antão, I picked up a national business magazine (Iniciativa 13: July-August 2006) and read some good news. From 15 to 30 September 2006, the period of the harvest, a warden was stationed on Raso for the first time. A warden for two weeks of the year may not sound like much. The effect remains to be seen, but at least this is a start.