I’m not a great traveller. Birding for me is not about new experiences but rather layering one observation on another. I do travel, although having another full time job, a large part of my holidays is spent writing. A major disadvantage of travelling is that someone (or worse, everyone) may see something good in Poole while I’m away. This obsession has been described before and the usual name for it, ‘twitching’, conjures up for me an image of hordes of nervous lemmings, without a thought in their head except for seeing a rare bird. However, a bird doesn’t have to be rare to knock me right off course.

Without wishing to be unkind to sufferers of the real thing, the phenomenon is best described as ‘bird Tourette’s’. For example, I was giving a talk in the lounge of the Haven Hotel, which has huge picture windows that look across the harbour mouth. While addressing a large group of work colleagues about something important, I involuntarily jerked my head round toward the window and cried, “cormorants”. 200 delegates looked at me astounded. I apologised, but from then on struggled to regain my train of thought. Cormorants? Having got past the initial stages of separating them from shags, I do find them fascinating, but I’ll come back to them later. Hamish Murray summed things up, pointing out that when you come out of a meeting you’ve forgotten the content in minutes, but see a good bird and you remember it for the rest of your life.

I blame my condition on Martin Cade, who started it all off by analysing where Dorset rarities had been found from 1983 to 1992. In the 1993 bird report, he wrote; “With its large concentrations of, for example, wildfowl and waders, Poole Harbour could be expected to attract its share of rarities. However this volume of common birds, and the sheer size of the site, seem to make rarity detection difficult, such that the Harbour and its environs attracted just 6% of the county’s rare bird total.” It was just a modest three-page article showing how great Portland was (41%) and how Weymouth (17%) and Christchurch (17%) accounted for most of the other rarities. 6%! We had been weighed and found wanting.

To become an official British rarity, a birder’s find has to be vetted by the ‘Rarities Committee’, which was set up by British Birds magazine in 1959. If you think you’ve seen a rare bird you can send a written description, drawing, photo and/or recording to the committee. Then 10 men decide whether they believe you to have seen and correctly identified your bird. They are like food critics. If they endorse your sighting, you are a five star Michelin birder but if they reject it you are doomed to months of introspection as you imagine them thinking of you as overenthusiastic, incompetent, a braggart or worse a liar. At present in Britain we have an excellent committee and great chairman, but the system has its flaws.

American Robin Turdus migratorius (Killian Mullarney)

At this stage I should explain I have tried to get help for my Poole Harbour bird obsession. I talked things through with my doctor. She thought it was healthy for a man to have a passionate interest (although now I think about it, she did encourage me to visit a therapist). It is true that many birders live long lives. Horace Alexander is an example of that. A life-long dedicated birder, he lived to be 100. He was also one of the first members of the Rarities Committee and had a good go at finding rarities in Poole Harbour.

Alexander was a Quaker, and his church sent him to India, where he spent a fair bit of his long life advising Gandhi, even introducing the concept of birdwatching to him. When India gained independence, he returned home to Swanage and liked to visit Poole Harbour. Birding with friend Martin Cutler on 17 January 1961, he describes “walking along the path from Holton Heath railway station towards Poole Harbour when … a bird settled on the telegraph wire, beyond an impassable thicket of gorse. It seemed to be a small thrush, which might have been a Song Thrush, only that it had a very distinct pale wing-bar; and this showed on both wings. It soon flew down and disappeared into the scrub. As it did so, I noticed white edges to the outer tail feathers, as in Mistle Thrush. But this was no Mistle Thrush; it was much too small, and the colour of its upper back and wings was too warm a brown: the lower back was paler” (Alexander 1974). Was there any such bird? Well in the end he found there was, namely the female Siberian Thrush.

Siberian Thrush is a mega-rarity, and Alexander’s credentials were spotless. He advised Gandhi on ethics, and his birding skills were well regarded. For reasons unknown to us, however, Siberian Thrush is not on the Poole Harbour list, nor is it listed as rejected. Who’s to say whether Horace made a genuine error, let his imagination run away with him, or was in fact correct with his identification? We all struggle with the thought that in the past a bird was accepted or rejected on the birder’s credentials.

Whether he was right or not, it’s these stories that fuel my passion. In The Sound Approach to birding (2006), I joked about being buried in Studland churchyard with this memorial engraved on the gravestone: “Here lies Mark Constantine. He found a Siberian Thrush in this churchyard.” What I didn’t write was that at a party, after a few beers, I mentioned this to Ian Stanley and we agreed that other birders would probably piss on it. So maybe it’s not such a great idea.

Trev Haysom is guaranteed a memorial in Studland churchyard. A stonemason and sculptor, he carved the man-sized stone cross on the green outside the church. I first met Trev as I nervously lowered myself down St Aldhelm’s crumbling cliff to go seawatching, using a metal cable and clutching frantically at the sea lettuce. He bounded past me, binoculars bouncing of his chest, with a cheery “Good morning,” and I joined him on the rocks some time later. His memorial? He found the American Robin in Poole Harbour, a great rarity and one that did enter the record books.

Returning from a Purbeck Natural History field trip on 15 January 1966, on a bleak midwinter day with a little snow on the ground, he found it foraging along the edge of the saltmarsh on Redhorn Point in Brand’s Bay. Later it moved to a more sedate residence in Miss M Crosby’s Canford Cliffs garden, where at one magical moment it shared the same bush as a Waxwing.

We did not have many rarities in the past, but there were some lovely birds. On 8 June 1967, Studland warden Bunny Teagle and his wife were with Bryan Pickess, driving from Arne to Corfe. Pulling over the hill past Slepe, they spotted a Roller sitting on a telegraph wire, right opposite Maranoa farm. Bryan swore in his excitement and Mrs Teagle, who had no sympathy for any kind of bird Tourette’s, gave him a good telling off.

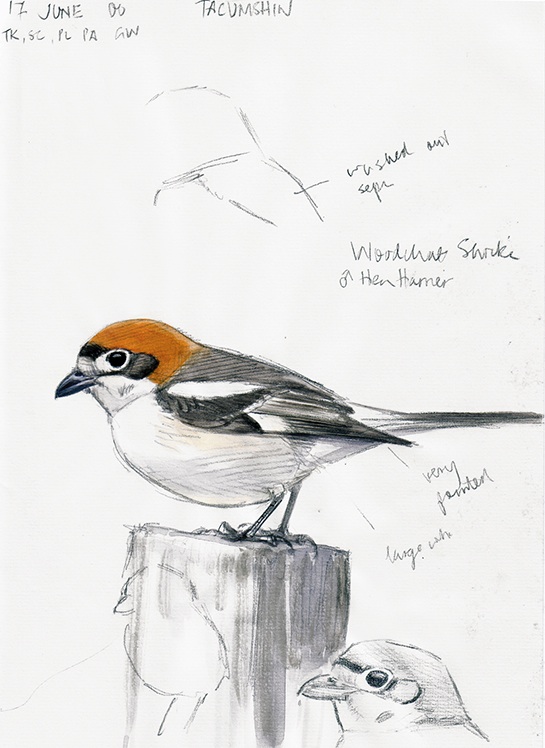

The rarity status of different birds has changed over the years. Woodchat Shrike was a national rarity when, on 31 May 1975, the Godfreys found an adult male sitting on a wire at Wytch. Now it has even turned up at Lytchett, and only needs a few brief notes sent to the local rarity committee.

Woodchat Shrike Lanius senator senator (Killian Mullarney)

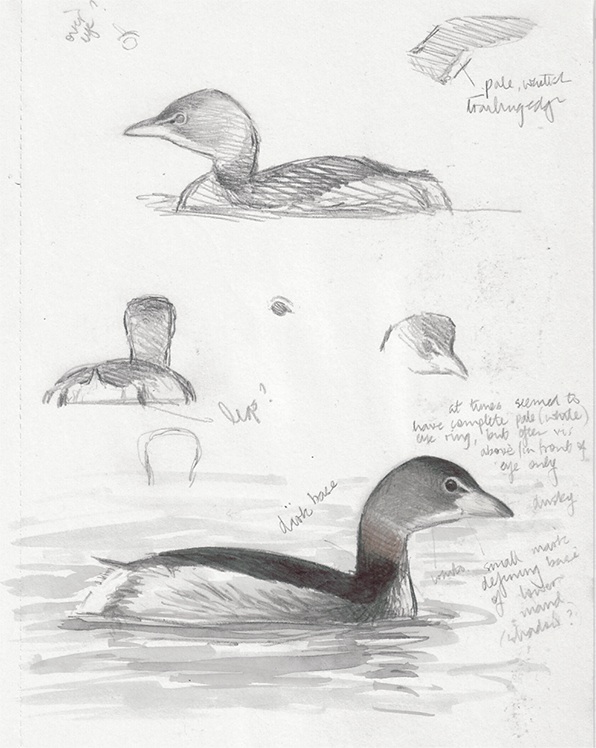

Iain Prophet was a serial rarity finder. He snared his first really rare Poole bird when down from Bristol on 10 February 1980, visiting the tiny triangular hide at Studland around teatime. It’s a nice place to watch Teal and sometimes Kingfishers, only this time it was a Pied-billed Grebe that came out of the reeds. Mo and I did see this one. Over several visits we watched it displaying, calling, and catching sticklebacks. It stayed till 28 April, moulting into summer plumage. Iain moved to Poole, and continued to find rarities, many of which stayed around long enough for us all to enjoy. He seldom misidentified a good bird and was always keen to share it, making sure everyone knew it was there.

Pied-billed Grebe Podilymbus podiceps (Killian Mullarney)

For birders, the number of rare birds they’ve seen or better found is the currency of birding, and if you have found a lot of good birds you are a millionaire. Taking this metaphor a little further, just as those that say “It’s not the money it’s the principle” really mean “it’s the money”, so those birders that say “I’m not really interested in rare birds myself” should always be included in any rarity ringaround. In the past, however, many birds didn’t hang around long enough for the finders to get to a telephone. Take for instance the Common Nighthawk.

I’m not sure who was waiting for who outside the toilets at the base of Ballard, but at 11:00 on 23 October 1983, Kate Massey, husband Mike and friend Margaret Howard watched a Common Nighthawk high over the trees and then over them. They wrote: “The bird flew rapidly into view, it twisted and turned as it flew. Its wings were long with pointed tips and noticeable patches of white on underside and top. The head was small, the tail was short with a small fork” (Green 1983).

I didn’t even hear about the nighthawk. The problem wasn’t just the lack of information, but the speed at which it moved. With no birdlines, mobile phones, internet or pagers, the nighthawk information would only arrive weeks later.

At Pilot’s Point at 13:45 on 26 November 1983, David Bryer-Ash saw a Little Swift as it flew low over the dunes. As he ran to the payphone, he met a YOC group led by Nigel Spring, most of whom were able to spot it as it attempted to feed in poor weather. By 15:20, several locals had seen it. I was blissfully unaware, entertaining my mother-in-law for lunch until around 16:00 when it was nearly dark. The next day I joined a scene unprecedented since the D-Day rehearsals. Over a thousand birders were searching for it. Keen Dorset lister Keith Vinicombe wrote: “It seems likely that this year’s individual succumbed after an appalling afternoon of cold, wet weather. The large turn-out of would-be observers the following day soon degenerated into the inevitable ‘social event’ and only the discovery of an exceedingly confiding female Lapland Bunting Calcarius lapponicus prevented an early adjournment to the cafes and pubs of nearby Poole” (Rogers & the Rarities Committee 1984). I saw the bunting, a good second prize.

Sharing birds had its drawbacks. Take Stephen Morrison’s experience. Quiet and awkward, he started coming to Studland as a boy, soon developing into a persevering birder. On the afternoon of 1 May 1987, he found Poole Harbour’s first Alpine Swift feeding over Godlingston Heath. He told Ewan Brodie who, unable to go, phoned Ian and Janet Lewis. They drove to Studland and walked the heath towards the Agglestone, finding the swift shortly before it headed over to Christchurch harbour. One of the rewards for finding a national rarity is seeing your name in British Birds magazine. It prints the names of the first three to send in a written report, in alphabetic order. When Stephen received the eagerly anticipated issue with the rarity report for 1987, he was dismayed to find Ian and Janet Lewis’s names first, making it look for all the world as if they had found it.

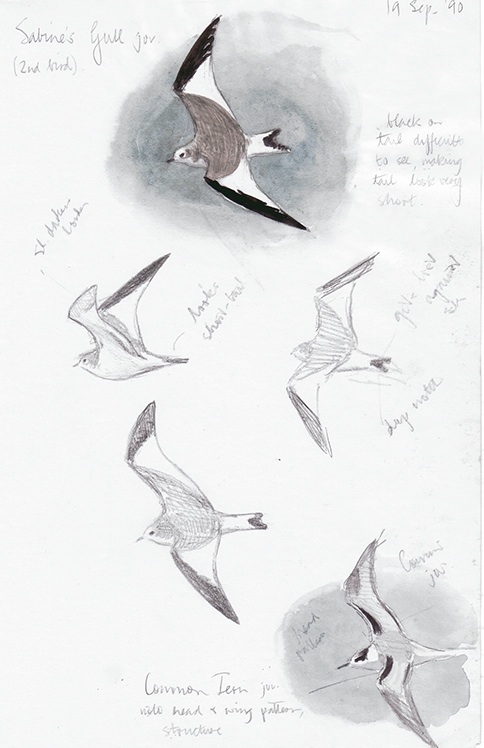

Sabine’s Gulls Xema sabini with Common Tern Sterna hirundo (Killian Mullarney)

Only two weeks after the swift, on 13 May, Stephen made another memorable find at the same location: a beautiful male Red-footed Falcon. On 24 May Mo, out birding with Rowena Bird, saw it again sitting on a flagpole on one of the greens on Studland golf course. Guy Dutson had also submitted the Red‑footed Falcon. We would joke afterwards that all this turned Stephen to the dark side, and after that he would only contact birders whose name followed his alphabetically.

Guy Dutson birded the harbour with Paul Harvey when they were kids, before going on to find fame elsewhere, Paul as warden of Fair Isle and Guy in Papua New Guinea. Asked about his childhood memories recently at a visit to the pub, Guy reminisced about Sabine’s Gulls in flocks on the south side of the harbour, ink-black Spotted Redshanks on Lytchett Pool, Twite in Ian’s kitchen and still regular, and Smew on the ice in the Wareham Channel. Matching his memories to the official record, “a flock of Sabine’s Gulls” could be in 1987 when two birds were together off Fitzworth on 5 September, ink-black Spotted Redshanks still turn up on Lytchett Pool, but Twite is really rare and the harbour’s second record was three in 1983 in Lytchett Bay, one of which did find its way into Ian’s kitchen to be ringed.

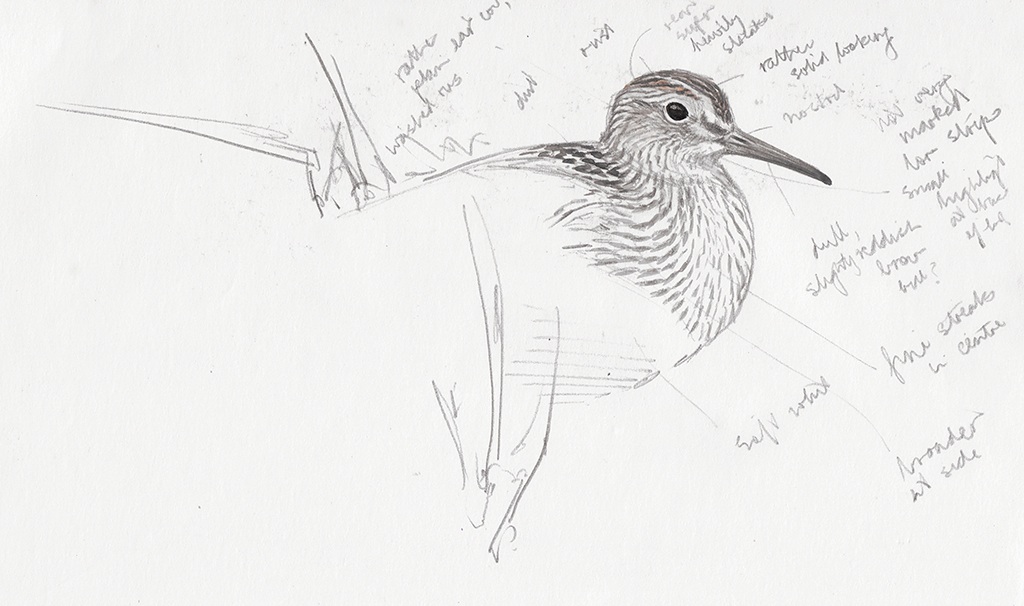

Pectoral Sandpiper Calidris melanotos, juvenile (Killian Mullarney)

One of the main reasons Robin Ward started the bird pub was to pass on news of rarities, and we were quickly rewarded when he himself found an adult female Wilson’s Phalarope in Holes Bay on 20 June 1988. Mo and I got great views.

If Martin is to blame for my obsession, Graham Armstrong was responsible for starting Shaun’s when he flushed a subadult Purple Heron from the back of Lytchett Bay Pool on 8 April 1992. Graham followed it into the far fields where it settled, then phoned out the news. Shaun, who had never visited Lytchett before, soon arrived and immediately fell in love with the place. He could see potential he felt others had overlooked. That autumn he visited Lytchett Bay every day after work for six weeks, but the next rarity there wasn’t his.

Shaun didn’t even get a call when Ewan found a lovely Pectoral Sandpiper there on 11 September 1992. Trying to avoid embarrassing episodes of bird Tourette’s at the office, Shaun had asked Ewan not to call him at work. That evening, instead of going straight to Lytchett Bay he had decided to play squash first, dropping in for a pint afterwards and finally arriving at the bay at around 18:30. On reaching the gate he noticed a neatly folded and tied note addressed “To Shaun”. He opened the note, “Pectoral Sandpiper on the pool all afternoon, we have all seen it but I couldn’t ring you, Ewan”. Frantically, he scanned the pool but it wasn’t there. Then he started to run up and down the lane, looking for gaps in the hedge to get different angles on the pool but, it was all in vain. By now it was low tide, and the bird had moved on, perhaps to join another seen on a flash pond at Swineham from 20 to 22 September. The latter was found by Stephen Morrison and shared only with the alphabetically appropriate Peter Williams.

People communicate well when they like each other, and the bird pub created friendships. It really started to come together for us all when Stephen Smith found an immature male Lesser Scaup at Hatch Pond on the evening of the 28 November 1992. Not getting good views in the failing light but very clearly seeing a scaup with strange vermiculations on its flanks, he discussed the bird at the pub with Shaun and me. Shaun rediscovered it on 4 December, and the following day, helped by phone calls to Killian and other friends, we were all able to help confirm its identity and also check that it had no leg rings. When we were content with its identification, we circulated the news, and the bird was enjoyed by 50 birders.

It felt good to identify what was then a first for Dorset and a fifth for Britain. Lesser Scaup was the last rare bird found in the period that Martin analysed, but it was the beginning of a great new chapter for the harbour when we would explore every nook and cranny to see what was hiding there.