Chapter 6: Paradise regained

Had I blurted out “Cormorants”, as I did at work, in the middle of reading to my fellow pupils at school, I would have been given a detention. It wasn’t unusual to find me in detention after class. The teacher would set appropriate extra work. “Right, Constantine, I want 200 lines starting with ‘I find cormorants fascinating because…’”

So I start writing my lines. “I find cormorants fascinating, because in Paradise Lost John Milton described Satan sitting ‘like a Cormorant’ in the tree of life, looking down on paradise…” Perfect! That’s how I see them,‑ perched on a post or dead tree, drying their wings in the sun and watching generation after generation of Poole folk going about their business. The bait draggers and clam boats, marines from the Special Boat Service, conscious of their image, speeding out from Hamworthy or floating down into Studland Bay on parachutes, lifeboat men on an exercise, searching for a dummy body, oyster seeders scattering the young oysters on Poole Harbour’s bed then hauling up the full grown catch to become dinners on Valentine’s day, busy, busy oilmen going to and fro, while peacocks fly into the trees to roost on Brownsea, and yachties head out to the Isle of Wight for lunch. They all pass a cormorant or two and some recognise them and some don’t, but very few realise how fascinating they are.

For a start there isn’t just one type of cormorant in Poole Harbour but two, maybe even three. They bring into question the idea of subspecies, and as a consequence they challenge birders, scientists and conservationists to question the status quo. As I’m only on imaginary detention, I feel free to return to the present and Google the term ‘subspecies’. I read, “Note that the distinction between a species and a subspecies depends only on the likelihood that in the absence of external barriers the two populations would merge back into a single, genetically unified population. It has nothing to do with ‘how different’ the two groups appear to be to the human observer” (Wikipedia, 22 September 2011).

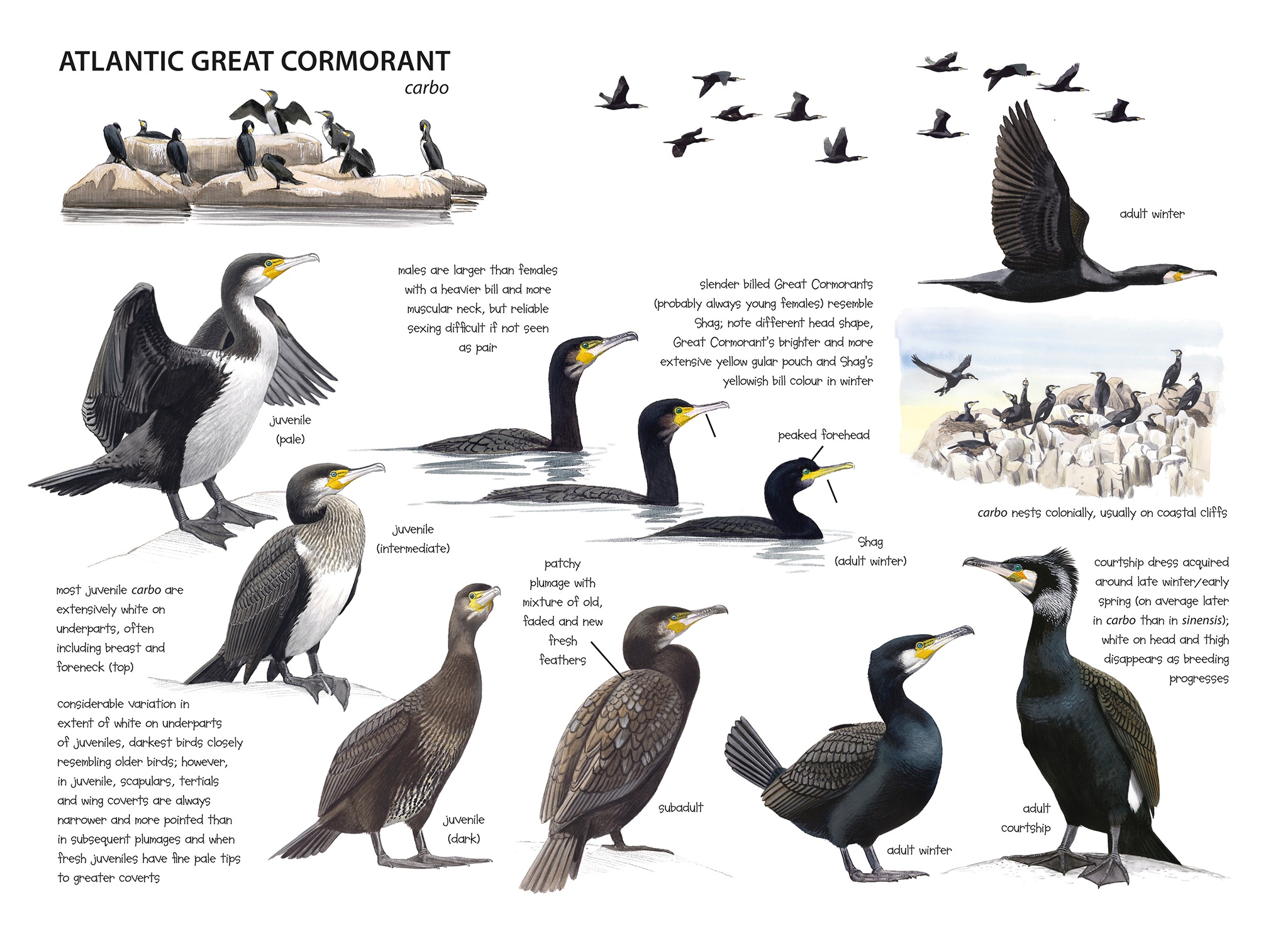

That certainly describes ‘our’ cormorants. Sorting through these inky black, coal black seabirds is a real art. First separating the Shags from the cormorants, then looking again for the far heavier Atlantic Great Cormorants Phalacrocorax carbo carbo which are the only type breeding in Dorset. They nest on the sea cliffs at Ballard and are declining a little more each year.

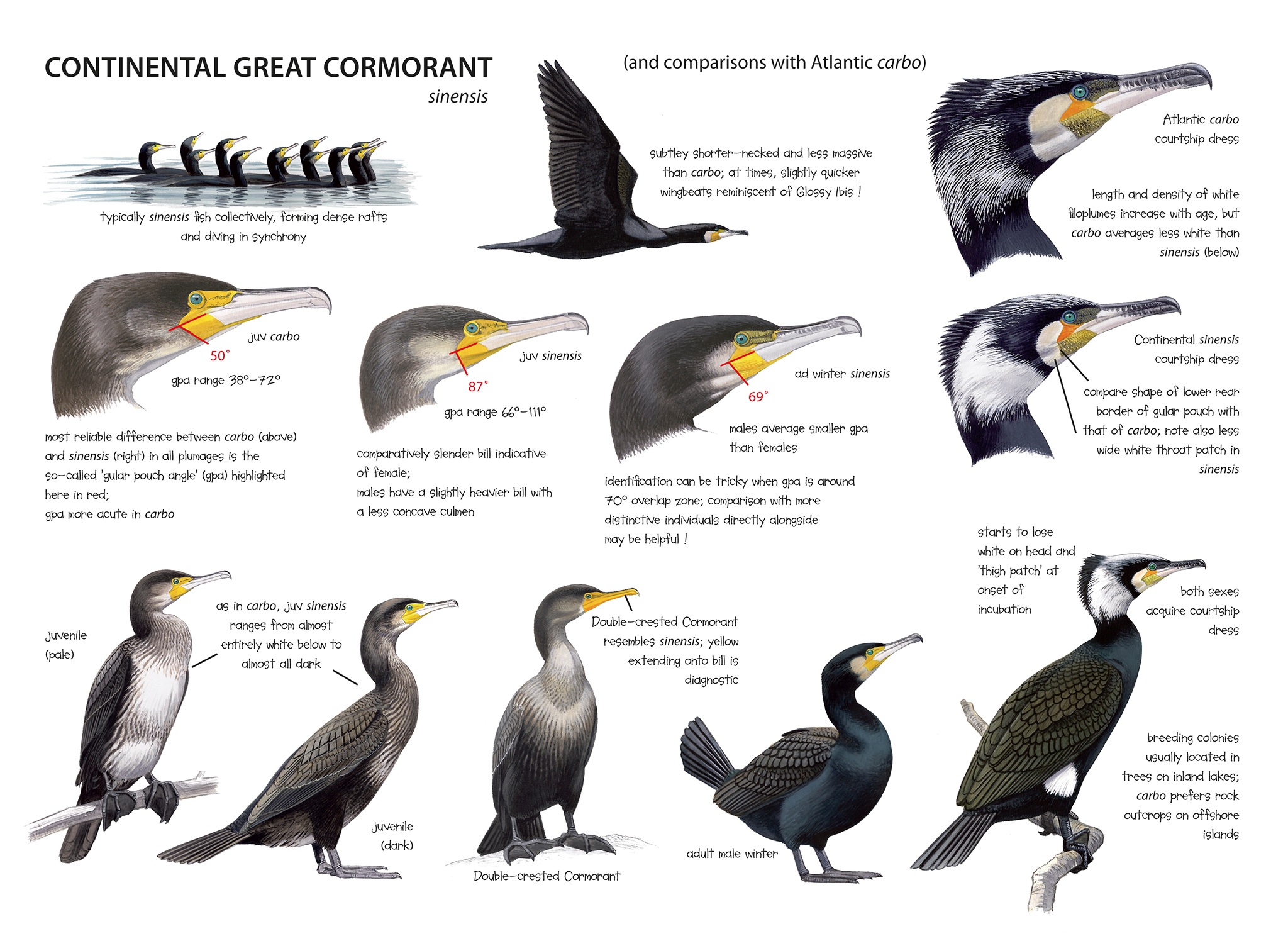

Continental Great Cormorants P c sinensis breed on the mainland of Europe in trees. They are highly migratory and happily feed inland on rivers, ponds and canals. The scientific name sinensis suggests that their roots could be China where many cormorants were (and some still are) kept as slaves to assist in the fishing industry. The technique is fairly simple. You starve your tame bird for a day, then tie a string around its neck and take it fishing. Each time it catches a fish you steal it. At the end of the day you have a bucket full of fish and feed a few to your slave. In the 16th century, cormorants were brought into France and especially England, and fishing with them had become a fashionable sport amongst the aristocracy by the 18th century (Olburs 2008).

Continental Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis, Amsterdamse Waterleidingduinen, Zandvoort, Noord-Holland, Netherlands, 27 April 2012 (Arnoud B van den Berg). At same nesting tree as where CD1‑31 was recorded. Though not as extensively white on the head as most breeding sinensis at the peak of courtship activity this bird, which was attending a nest with eggs or hatchlings, showed more extensive white than most others present at the time at this site. In sinensis, the white patch on the cheek/throat is about the same width as the gular skin in front of it; in carbo, the white patch is considerably wider.

Nobody can tell for sure whether sinensis cormorants were released into Poole Harbour in the 16th century, but we do know from a study in the Baltic where large numbers of sinensis breed today that the skeletal remains of cormorants that were there during earlier times are the size of carbo. “Precisely when… sinensis immigrated into the Baltic is unknown, but it must have occurred sometime between 1500 and 1800 AD” (Ericson & Carrasquilla 1997).

It would be fun, just for the duration of my detention, to assume that having discovered the best fishing cormorant known to man we brought it into Europe, which then escaped into the wild and has been pushing nominate carbo further west ever since. However, genetic evidence suggests that there was a refuge of European sinensis in the Danube basin during the last ice age, and the Chinese birds are distinguishable from European ones, having an even greater gular angle than ‘our’ sinensis. So, whatever role the slave cormorants from China may have had, there had already been sinensis in Europe for thousands of years.

In 1966, John Ash recorded three continental birds flying into Poole Harbour on 13 February. But they had probably been sneaking around in the harbour way before that, because Britain’s first documented record of sinensis was taken 11 miles up the road at Christchurch in 1873.

Continental Great Cormorants seem to have increased in the harbour over the last 10 years, mirroring a similar increase across the whole of eastern and southern England. Whether this is just due to increased awareness is difficult to say. Whenever one of us makes an effort, we can identify a few continental birds, and they have been seen in the Wareham Channel, sitting in groups on the Keysworth shore, on Hatch Pond, in Poole Park and perched on Poole Quay breakwater, among other places. However, we have not found any breeding yet.

Various studies have shown that in some inland tree colonies in England and France, both carbo and sinensis are present (eg, Goostrey et al 1998, Winney et al 2001). Just how much hybridisation is going on is unclear, with different genetic analyses giving different results. So our Wikipedian distinction between subspecies and species is difficult to apply. Whatever may be going on, carbo and sinensis do represent clearly separate lineages with a long history of separation, largely in different habitats. If any mixing is going on now in Britain and France, it is taking place in the tree-nesting colonies and not on cliffs, which sinensis appear to avoid (Marion & le Gentil 2006). So, we can assume that our Dorset cliff-nesters are clear examples of carbo.

Atlantic Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo carbo, Rosslare, Wexford, Ireland, 18 February 2012 (Killian Mullarney). The bristle-like white filoplumes on the top and sides of the head and the prominent white thigh patch are features of courtship plumage. Acquired in late winter/early spring, they will have largely disappeared in most birds by late spring.

Curiously, ‘carbo’ from northern Norway do not appear to be closely related to carbo from elsewhere, despite their similarity in size and habitat. It has been suggested that they are more closely related to Japanese Cormorant P capillatus, and may have colonised from the Pacific via the Northeast Passage (Marion & le Gentil 2006). Might these birds also visit Poole Harbour in the winter?

We didn’t really understand how many of our cormorants were migrants until one long summer’s day at Brownsea lagoon, when Jim and Stan identified large numbers of juvenile sinensis. They were using a new technique pioneered by Per Alström, which involved noting the size and angle of the yellow gape. Time passed, then one day Nick had a go at photographing a series of random cormorants scattered about the harbour. When he got out his protractor he found that over 50% of these birds could be identified as sinensis.

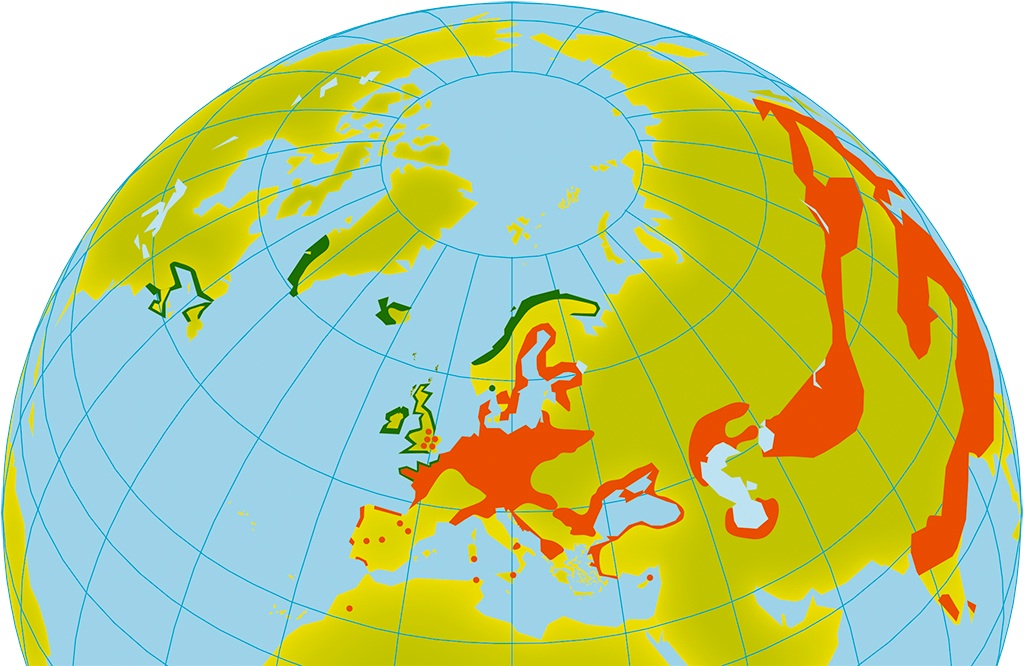

Approximate breeding ranges of Atlantic Great Cormorant Phalacro-corax carbo carbo (green) and Continental Great Cormorant P c sinensis (red). Continental sinensis is so adventurous that we can soon see the colours on this map changing, and indeed in Britain the breeding numbers are on the increase. On the other hand, in recent years, also a handful pairs of Atlantic carbo have been found in Continental sinensis colonies along continental North Sea coasts, such as in the Netherlands. Atlantic carbo also breeds along the coasts of north-western France but it is unclear how far south and inland it occurs.

Now intrigued, the rest of the Sound Approach team followed up, with Killian making a trip to Brownsea on 7 February 2011. Back in Wexford, Ireland, where Killian lives, all the cormorants are carbo. On Brownsea, he found that of the cormorants roosting in the lagoon, at least 80 were carbo while over 100 were clearly sinensis. Another 235 or so were hidden behind them and could not be seen well enough for identification.

We then turned our attention to their sounds. I’ve only recently noticed cormorant vocalisations. Lars Svensson too, apparently. In the Collins bird guide (Mullarney et al 2009), he only describes “Various deep, guttural calls at colony”, but there is far more to them than that. Now I realise they are very noisy, their calls filling Brownsea lagoon every night (CD1-27). They sound so distinctive to me now, but suppose I mistook them for gulls or ducks in the past.

CD1-27: Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo Brownsea lagoon, Poole Harbour, Dorset, England, 18:35, 11 September 2011. In this recording of birds arriving at a large roost, both carbo and sinensis were present. Background: Canada Goose Branta canadensis, Greenshank Tringa nebularia and Sandwich Tern Sterna sandvicensis. 110911.MC.183554.02

So we asked ourselves, are there any vocal differences between carbo and sinensis? The most serious attempts to understand cormorant vocal behaviour were published without accompanying recordings or sonagrams (Kortland 1938, 1995, van Tets 1965). So by necessity, their descriptions of the different call categories are phonetic or as we call it, ‘birdie talk’. Among the sounds heard most often from cormorants are loud, rolled ‘r’s. Have a listen to these rolled ‘r’ calls of carbo, recorded accidentally after the breeding season in Ireland (CD1-28), while trying for Roseate Terns.

CD1-28: Atlantic Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo carbo Carnsore Point, Wexford, Ireland, 23 August 2002. Raucous calls and slow rolled ‘r’ call of a successful attacker in a ‘perch dispute’. Background: Common Tern Sterna hirundo, Roseate Tern S dougallii, Pied Wagtail Motacilla yarrellii and Grey Seal Halichoerus grypus. 02.039.MR.03951.22

In this case, one adult was displacing another from a post, a ritualised behaviour described by Kortland (1938). The attacker arrives giving a series of raucous calls with its plumage somewhat puffed out, its neck in an S-shape, and with the hyoid bone sticking out in its throat. Then when it has successfully expelled the other, it gives a couple of triumphant rolled calls in an erect posture with a thick neck and its bill pointing slightly downwards.

In most of our cormorant recordings, especially those in large roosts and breeding colonies, it is much harder to know what was going on. You can often hear calls very similar to those heard in ‘perch disputes’. Other situations where calls with a rolled ‘r’ sound can be heard are summarised in BWP (Cramp & Simmons 1977). It can be hard to be sure whether you are hearing a rrrrr (pre-flight/pre-hop call), rooor (post-landing call), r-r-r-r-r-r (given during ‘gape display’) or rrrrr (associated with rubbing and entwining of necks). This is the trouble with ‘birdie talk’ descriptions, lacking sonagrams.

At the risk of mixing up similar-sounding calls associated with different behaviours, Magnus checked and compared the quality of the rolled ‘r’ in our carbo and sinensis recordings and found that in sinensis it seemed to sound faster on average. Listen to these sinensis at a post-breeding roost in Bulgaria (CD1-29) and see if you agree that they sound slightly different from the carbo you just heard. Magnus then analysed sonagrams of 20 rolled calls of carbo from Ireland and 29 of sinensis from Bulgaria and the Netherlands, recorded both in breeding and non-breeding contexts. In order to complete the first four rolls of a rolled ‘r’ call, carbo took an average of 12% longer than sinensis, or in other words carbo roll their ‘r’s more slowly.

CD1-29: Continental Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis Burgas lake, Burgas, Bulgaria, 09:19, 20 September 2007. Cormorants arguing over perches at a roost as new birds arrive. Rolled ‘r’ calls of several individuals can be heard. Background: Yellow-legged Gull Larus michahellis and European Robin Erithacus rubecula. 070920.MR.091907.01

Listen to another recording of carbo (CD1-30). These Irish breeders were nervous, because Killian was rather close to their colony. At 00:05, a rolled ‘r’ call can be heard from a presumed female, and despite the anxiety, it still sounds marginally slower than average calls of sinensis. This may be related to the larger size of carbo, and perhaps other physical differences. After all, if their gular patches differ, why not the anatomy of their throats?

CD1-30: Atlantic Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo carbo Saltee Islands, Wexford, Ireland, 12:05, 10 April 2011. Two adults on different nests: a male slightly to the left and a presumed female slightly closer in the centre, calling in response to Killian’s movements. The presumed female gives a rolled ‘r’ call at 00:05. Background: Eurasian Wren Troglodytes troglodytes, Black-legged Kittiwake Rissa tridactyla and large gull Larus. 110410.KM.120550.02

Now listen to another recording of sinensis, this time from a large colony in the Netherlands (CD1-31). In this recording, you can hear various calls with a rolled ‘r’ quality, perhaps associated with a wider range of behaviours and displays than in a post-breeding roost. Again the ‘r’s seem to be rolled a little faster than in carbo. Whether the small vocal difference between carbo and sinensis still stands when calls of known sex and from a narrowly defined behavioural context are compared will have to wait for a more thorough study. In the meantime, we should start scrutinising their behaviour more closely.

CD1-31: Continental Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis Amsterdamse Waterleidingduinen, Zandvoort, Noord-Holland, Netherlands, 19:56, 11 May 2011. Sounds of a colony, including a variety of adult calls with a rolled ‘r’ sound, and high-pitched whistled begging calls of nestlings. Ignore the loud calls of a Grey Heron Ardea cinerea from 1:00 in the recording. Background: Common Chiffchaff Phylloscopus collybita and Willow Warbler P trochilus. 110511.AB.195608.01

It’s only recently that cormorants have gained some protection in the UK. Trev Haysom’s father would take friends along the Ballard cliffs to shoot them. “The cormorants, nesting here and feeding in Poole Harbour were shot as rivals by fishermen who claimed a government bounty.” On one occasion the birds got off lightly when “one careless man shot through the bottom boards” (Cooper 2004).

Fishermen also caught cormorants and shags by applying glue to suitable perches and returning later to cut off their tails to collect a bounty. Persecution is still going on, here and there, throughout Europe. As a recent example, in an isolated Mediterranean colony of carbo on the island of Sardinia, up to 1000 were being killed each winter in the ‘90s, until by 2002 they were all gone. It was much the same in the Netherlands where numbers of sinensis were kept to 500 pairs per colony according a quota system, until the creation of the IJsselmeer from the Zuiderzee in the ‘30s distanced the cormorants’ breeding colonies from their feeding grounds, and the bird got into difficulties. The collapse in breeding numbers was reversed in the ‘70s when they started to nest in newly created polders. Cormorants started to be noticed on Brownsea lagoon in 1971 when the warden wrote, “suddenly 100 birds started to roost on the seawall or within the lagoon especially in late summer”

(Wise 1981). Perhaps this was the start of the most recent influx of sinensis into Poole Harbour.

For years we counted cormorants flying to and from a roost somewhere out in Poole Bay and thought we were getting all the birds of the harbour. However, the Brownsea roost and a third roost on Long Island or Arne beach weren’t counted at the same time. On the morning of 2 November 2009, Nick and I counted 689 heading across the harbour to fish, with others flying inland over our heads at our eyrie at Constitution Hill. This was a new county record and puts Poole among the top five sites in Britain.

This is not all good news. Fishermen still hate cormorants and the current British Fisheries Minister Richard Benyon MP is a fisherman. He recently announced a review of the current licensing regime for cormorant controls, whereby Poole fishermen will be able to take matters into their own hands to protect their local fish stocks. So, while still discussing speciation, we could see Atlantic Great Cormorants heading for extinction as a breeding bird as efforts to control cormorant numbers, though ill informed and ill judged, get the go-ahead from the government’s Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA).

Paradise lost and then regained fits my view of these birds in Poole Harbour. It would be so sad to see paradise lost again as the last local breeding Atlantic Great Cormorants are exterminated, hanging dead from the channel posts, waiting for fishermen to cut off their tails for a bounty.