Killian Mullarney

Text by Magnus Robb.

On 28 May 2006, while birding in the Bay of Biscay, Jean-Marie Durand and Gregory Gomez discovered a first for the Atlantic. Under the wooden veranda of a holiday villa in a suburban pine- wood near the mouth of the Arcachon basin, Gironde, France, they found two breeding pairs of Scopoli’s Shearwater. This was remarkable not only because it constituted the first known breeding outside the Mediterranean, but also because the birds were not breeding on an island (Mays et al 2006).

Since the mid-1970s, birders had noticed concentrations of ‘Cory’s Shearwaters’ at the mouth of the Arcachon basin, and further south along the Biscay coast (Campredon 1976, Yésou 1982), and in the summer of 1986, they started to notice behaviour suggestive of breeding (Mays 1986). As the nearest known Cory’s bred in the Berlengas, Portugal, about 1100 km by the shortest sea route, this was an exciting development. Then when eight were trapped and measured in 1988, they turned out to be Scopoli’s Shearwaters. The surprising news was apparently never published, or simply disbelieved, and even the French authors of the BWP Update on Cory’s and Scopoli’s described the Biscay shearwaters as “of unknown origin” (Thibault et al 1997). On 2 August 2004, a pelagic trip off the Isles of Scilly documented the first Scopoli’s for Britain (Fisher & Flood 2004). Even now, few British birders are aware that there are breeding Scopoli’s Shearwaters only 700 km to the south-east of Scilly.

Prior to their discovery in spring 2006, Durand and Gomez received a tip from shore-based anglers who said that for several years, they had been hearing nocturnal songs of large birds coming from the sea. When they checked this out on 10 May 2006, they found six Scopoli’s Shearwaters displaying at dusk over a villa garden. Keeping a close watch for the next few days, they observed copulation at sea, a few hundred metres from the shore. From 18 May, the shearwaters’ appearances became more irregular, and on some nights they were absent (in retrospect, this could be explained as the pre-laying exodus). After their return on 27 May, some were seen disappearing into a gap underneath the villa’s wooden veranda. Finally, on 28 May, a spotlight revealed two nests: an egg in one and a brooding adult on the other. Another burrow containing a nestling was later found at the foot of a nearby pine tree, bringing the total to three pairs.

Even before the captures back in 1988, calls heard at Arcachon led to the belief that the summering shearwaters were Scopoli’s. There are diagnostic differences between calls of Cory’s and Scopoli’s Shearwaters, which are easy to learn. Elsewhere, call differences have also been used to identify a Cory’s visiting the island of Skellig Michael in Kerry, Ireland, 1400 km north of the Berlengas. I heard this male myself in August 2006, two years after it was first discovered. So far, it has not been caught or seen in daylight, so calls have been the only way to exclude Scopoli’s.

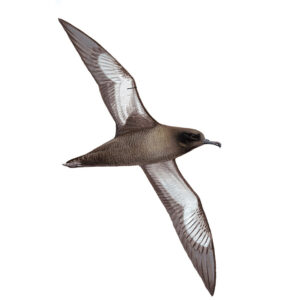

Scopoli’s Shearwater Calonectris diomedea, Arcachon basin, Gironde, France, 13 August 2006 (Jean-Marie Durand). One of the first known to have hatched in an Atlantic colony.

To learn more about call identification, I obtained permission to visit a medium-sized colony of Scopoli’s Shearwaters on a tiny island just off north-western Mallorca. Miguel McMinn, a friend who works with seabirds in the Balearic Islands, took me there by zodiac in the evening and agreed to pick me up at dawn. Before it got dark, I searched for the main concentrations of nests. Some could be found under dwarf palms and low scrub, but most were among boulders on the west side, facing out into the Mediterranean. I found a quiet valley, sheltered from the slight breeze, where the slight surf was out of earshot. When the first shearwaters arrived after dark, it was their wing sounds that gave them away. CD1-23 and CD1-24 were recorded about an hour later. Many shearwaters were still calling from the air, but others had landed and were calling on the ground. On this moonless night, waves of intense activity erupted every few minutes.

CD1-23: Scopoli’s Shearwater Calonectris diomedea Mallorca, Balearic Islands, 23:25, 25 July 2006. Sound of a colony a day after new moon, and an hour after the first individuals arrived. The first call series (0:01-0:08) is delivered by a male, and a female soon joins in (0:06-0:13). Both sexes can also be heard on the ground. 060726.MR.232531a.01

CD1-24: Scopoli’s Shearwater Calonectris diomedea Mallorca, Balearic Islands, 23:25, 25 July 2006. This cut begins with the close approach of a female. On the left, one male’s calls become markedly higher-pitched from around 1:21, a sign that things are getting fairly heated. 060726.MR.232531b.01

When you compare these Scopoli’s to the Cory’s Shearwaters in CD1-17 you can hear that, like for example Carrion Crow Corvus corone and Rook C frugilegus, they sound superficially rather similar. In both cases, the recordings were made with exactly the same equipment, and a mixture of flying and grounded birds are calling within a few metres of the stereo microphones. The most striking difference from Cory’s is that Scopoli’s tends to deliver its loud notes in twos, then ends with a breath note, whereas Cory’s usually delivers them in threes. In addition, the two notes of Scopoli’s are longer, and consequently their delivery sounds more laid back. A third difference is that there are prominent high-pitched, inhaled ‘hiccup’ sounds between the two loud notes of Scopoli’s. If you listen carefully to Cory’s, you may occasionally hear inhaled ‘hiccups’ between their three exhaled notes, but these are rarely prominent. When you consider these differences together, it is possible to separate Cory’s and Scopoli’s confidently, just by listening to their calls.

CD1-17: Cory’s Shearwater Calonectris borealis ‘Captain Kid’s Cove’, Selvagem Grande, Selvagens, 19:00, 27 June 2006. Thousands flying over a large colony by daylight. The first one to fly past at close range (0:02-0:06) is the male shown in the sonagram. 06.008.MR.01626.01

Bretagnolle & Lequette (1990) compared the calls of Scopoli’s Shearwaters from Porquerolles and Frioul islands in the French Mediterranean, with Cory’s Shearwaters from the Selvagens, and confirmed that there were significant differences for both sexes in the number of notes, note length, and the length of the gap (including the ‘hiccup’) between notes. Frequency also differed, but only in males: calls of male Scopoli’s averaged slightly higher-pitched than male Cory’s.

All these characters are subject to individual variation. In Scopoli’s Shearwater, before going into two-note couplets, a series of calls may ‘warm up’ with one or two rather long notes. You can hear a male do this at the start of CD1-23. Cory’s Shearwater may also give one- or sometimes two-note calls, but nearly always progress to three-note calls by the end of a series. Equally, birds of either taxon may sometimes have too many notes. You can hear a couple of four-note Cory’s in CD1-17 and the occasional three-note Scopoli’s in CD1-23.

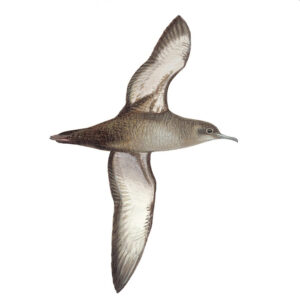

Scopoli’s Shearwater Calonectris diomedea, between Mallorca and Menorca, Balearic Islands, 12 March 2007 (Arnoud B van den Berg)

According to Thibault & Bretagnolle (1998), only 1-3% of Scopoli’s Shearwaters have three-note calls. When over 400 males from both shearwaters were analysed, none showed two call characters of the other, such as number of notes plus note length, at the same time. For example, the minority of Scopoli’s with three-note calls still have longer notes and a slower delivery than Cory’s Shearwater, as well as more prominent ‘hiccups’ between the notes.

Researching less well-known species pairs is always a little contentious at first. But we are now comfortable with the existence of Eurasian Rock Anthus petrosus and Water Pipits A spinoletta, for instance, or even Balearic P mauretanicus and Yelkouan Shearwaters P yelkouan. The first time many birders became aware of Scopoli’s Shearwater was when the Dutch committee for avian systematics (CSNA) split it from Cory’s Shearwater, based on differences in biochemistry, voice and morphology (Sangster et al 1998, 1999). Not long afterwards, Gutiérrez (1998) published a paper on separation in the field. He showed that in Cory’s, the primaries are usually all-dark on the underside of the wing, contrasting strongly with a rounded white panel formed by the primary coverts. In Scopoli’s, each primary typically shows a prominent white wedge on its inner web, projecting well beyond the coverts. Seen from a distance, this creates quite a different underwing pattern, with the white area less sharply defined, and reaching further into the wingtip. Studies on skins of known provenance have shown that the differences are statistically significant (R Gutiérrez pers comm), although individuals certainly exist that are not easy to assign to one or the other species.

There is also considerable variation in size. Scopoli’s Shearwater shows a marked cline from east to west, from the smallest ones breeding near Crete, to the heaviest ones breeding in the Columbretes off Spain (Thibault et al 1997). Curiously, the Biscay birds are as small as Scopoli’s from the eastern Mediterranean (Mays et al 2006). Cory’s Shearwater averages considerably heavier, and shows no such east-west cline in size. If anything, there is a north-south cline, with the largest birds in the Azores and the smallest ones in the Canary Islands.

Cory’s Shearwater Calonectris borealis, male (Edward Soldaat)

Scopoli’s Shearwater Calonectris diomedea, female (Edward Soldaat)

Cape Verde Shearwater Calonectris edwardsii, unsexed adult, probably female (Edward Soldaat). All three skulls shown at same scale.

Gómez-Díaz et al (2006) looked at the biometrics and DNA of Calonectris shearwaters, and attempted to reconstruct their evolution and biogeography. Their analysis was based on 12 colonies of Cory’s, 14 of Scopoli’s, one colony of Cape Verde C edwardsii and one of Streaked Shearwater C leucomelas from the western Pacific. When various measurements were combined statistically, four clear-cut ‘morphospecies’ emerged, corresponding to the four known taxa, with Cory’s and Scopoli’s the most similar.

For the genetic part of their study, Gómez-Díaz et al examined two different segments of the ring-shaped mitochondrial DNA molecule (mtDNA). The ‘cytochrome b’ gene is a more slowly evolving segment, which allows scientists to reconstruct lineages between 0.1 to 30 million years ago, while the ‘control region’ is a more rapidly evolving segment, more useful for resolving recently diverged lineages (Maclean et al 2005). For Calonectris shearwaters, Gómez-Díaz et al obtained the same clear-cut phylogeny from both segments of mtDNA. Nobody was surprised to learn that Streaked Shearwater is the most divergent member of the group, both genetically and geographically. Much less expected was the finding that Scopoli’s Shearwater is more closely related to Cape Verde Shearwater than to Cory’s Shearwater, and that these three branches of the phylogenetic tree diverged around the same time.

Sometimes when DNA studies come up with surprising results, they seem to invite ridicule. Although this may be warranted at times, sceptics may be overly influenced by visible characters. In many bird families, plumage and structural differences evolve rapidly and play an important role in sexual attraction. In pelagic seabirds like petrels, where there is a limited range of optimal designs, structure and coloration may be similar across a wide range of species. Plumage patterns are thought to be correlated with feeding techniques and foraging group sizes at sea, rather than courtship displays (Bretagnolle 1993). Petrel sexual activity takes place mainly on land and at night, so sounds are more important than visual displays of plumage.

Scopoli’s Shearwater Calonectris diomedea.

Recording location indicated by arrow: Mallorca, Balearic Islands.

The Calonectris shearwaters are thought to be closely related to the large Puffinus shearwaters, including Great Shearwater P gravis and Sooty Shearwater P griseus (Nunn & Stanley 1998). Most of the Calonectris and large Puffinus shearwaters have two-note calls. This includes Scopoli’s, Cape Verde and Streaked Shearwaters, but Cory’s Shearwater is an exception. Presumably, the common ancestor of all these shearwaters had two-note calls, which were retained by the first Calonectris. After Streaked split from the group, the common ancestor of Cory’s and Scopoli’s/Cape Verde still had two-note calls. Sometime after these two branches separated, Cory’s must have evolved a three-note call, but Scopoli’s and Cape Verde retained the two-note call of their ancestors. This actually tells us nothing about the relationship between Scopoli’s and Cape Verde, but it does reinforce the idea that Scopoli’s and Cory’s are less closely related than they appear.

Gómez-Díaz et al devoted much thought to the historical biogeography of Calonectris shearwaters. According to their reconstruction, this group probably diverged from other shearwaters in the Atlantic more than five million years ago, the age of the oldest Cory’s Shearwater-like fossils from South Africa and South Carolina, USA. The separation from Streaked Shearwater must have taken place around three million years ago, when the Panama land bridge separated the Atlantic from the Pacific. Genetic studies date the separation of Cory’s and the Scopoli’s/Cape Verde Shearwater ancestor to about one million years ago, while Scopoli’s and Cape Verde diverged about 300 000 years later.

Scopoli’s Shearwater Calonectris diomedea, Viareggio, Toscane, Italy, 8 September 2007 (Daniele Occhiato)

In the present day, Scopoli’s Shearwaters leave the Mediterranean to winter in seas from South Africa to the equatorial mid-Atlantic. This has recently been confirmed by pelagic surveys off South Africa (Camphuysen & van der Meer 2001) and satellite tracking of four adults from Crete (Ristow et al 2000). So, a high percentage of Scopoli’s pass the Cape Verde Islands region twice a year. If this migration route is an ancient one, colonisation of these islands by a Scopoli’s-like ancestor becomes easier to understand.

This brings us back to the Arcachon basin on the French Atlantic coast, where a similar colonisation event may be taking place now. The new colony should satisfy adherents of the biological species concept, who hold that a lack of interbreeding, rather than a separate evolutionary history, is the key to defining a species. Scopoli’s Shearwaters making their way to Arcachon from their known wintering grounds, or from the Mediterranean, pass colonies of Cory’s Shearwaters in the Berlengas, Portugal. Although there are isolated cases of hybridisation elsewhere (Thibault & Bretagnolle 1998, Martinez-Abrain et al 2002), the fact that Scopoli’s have founded a new Atlantic colony of their own suggests that they no longer recognise Cory’s as potential mates.

For a flirting seabird at night, looks are irrelevant, but a sexy voice is a must. None have voices as sexy as Calonectris shearwaters. From a human point of view, they seem to have got it the wrong way round. In Scopoli’s Shearwater, as in Cory’s Shearwater, males are high-pitched, while the females are lower-pitched. In fact, this is the polarity in most petrels. At the start of CD1-23, you heard a male and female duetting in flight: first the male and then the female. The sexual difference is even more striking in Streaked Shearwater. Males pitch their calls at around 4-5 kHz, as high as a Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos, while female Streaked sound much like male Scopoli’s.

Sexual dimorphism in voice is not always correlated to size. In all Calonectris, males are heavier than females, the opposite of what their voices suggest. The extreme degree of vocal contrast sets Calonectris apart from the other shearwaters. The large Puffinus shearwaters they share a common ancestor with also show sexual differences in the voice, but not to the same degree.

The male-female difference can be heard very clearly in the duets in CD1-25. These were recorded on another islet off Mallorca in March 2007, very early in the breeding season. Perhaps the male and female in the recording were renewing their pair bond for the first time this season. The male was usually the one who started the duet, often using a few single notes somewhat different from any I have heard in flight, and then the female joined in. Both male and female usually started and finished their call series with a phrase or two consisting of a single exhaled and a single inhaled note. The two-note calls in the first duet are rather well synchronised. Perhaps this was a long-established pair, very familiar with each other’s calls.

CD1-25: Scopoli’s Shearwater Calonectris diomedea Mallorca, Balearic Islands, 21:16, 9 March 2007. A male and a female duetting under a rock at the start of the breeding season. Background: Yellow-legged Gull Larus michahellis. 070309.MR.211631.00

During my July visit the year before, close synchronisation between males and females was much less in evidence. Most of the callers were probably non-breeders, and many were probably still looking for a mate. Some of the Scopoli’s Shearwaters I heard in the colony were very young indeed. Weak, high-pitched piping betrayed the presence of nestlings, most of which would have been little over a week old. The one in CD1-26 was giving ‘long begging calls’ very similar to those of the much older Cory’s Shearwater nestling in CD1-21. Both parents were present in the burrow, hidden from view beneath a large boulder. When the nestling stopped calling for a moment, I could hear that it was being fed. Sometimes there was a rattling sound as the bills touched (eg, 0:12), and I could even hear a liquid sound as fish soup was being served (0:36). The adult male called very quietly at times (eg, 0:31), giving muted calls I never heard except when a nestling was being fed.

CD1-26: Scopoli’s Shearwater Calonectris diomedea Mallorca, Balearic Islands, 23:14, 26 July 2006. An adult male feeds a nestling, which gives long begging calls. Rattling sounds of bill contact, and fluid sounds of feeding can be heard. Background: other individuals calling overhead. 060726.MR.231424.00

Scopoli’s Shearwater Calonectris diomedea, between Mallorca and Menorca, Balearic Islands, 12 March 2007 (Arnoud B van den Berg)

Looking back on this visit, being intimate with shearwaters so close to a popular tourist island was a great privilege. When activity died down over the next hour or so, I decided to look for a good place to get a few hours of sleep. The colony was crawling with large black nocturnal beetles. There were midges in sheltered spots, but I found a bare, flat rock in an open spot, several metres from the nearest nests, and cooled by a slight breeze. Making a kind of a pillow with my rucksack, and despite the lack of a sleeping bag, I was so tired I had no problem falling asleep.

I woke about 05:00 when a female Scopoli’s Shearwater flew so close, my chest resonated with her sonorous, throaty voice. Without even having to sit up, I could have reached out and touched her the next time she came round. The skies were already getting lighter, and the pre-dawn exodus was nearly over. Not far away, a nestling was calling from underneath a dwarf palm. The intensity of its calls told me that an adult was feeding it. The nestling kept demanding more, but soon the adult had given all it had. Dawn was beginning to break, and it was time for the adult to leave. I crept over to make a recording, just in time to catch the last begging calls of the night. Shuffling towards the fringe of the dwarf palm, the adult clambered over my microphone cables and flew forcefully out to sea (CD1-27).

CD1-27: Scopoli’s Shearwater Calonectris diomedea Mallorca, Balearic Islands, 05:28, 27 July 2006. Long begging calls of a nestling; its parent clambers over the microphone cables and departs. Background: other individuals calling overhead. 060727.MR.52834.00