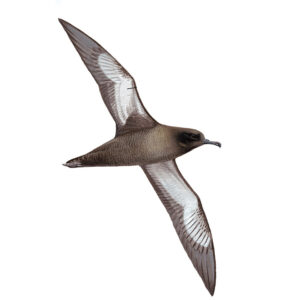

Killian Mullarney

Text by Magnus Robb.

When the moon set below the horizon, I made my way through the night towards the ridge of rounded hills in the northern part of Raso. Tired from stumbling over boulders in the dark, I was relieved to find a small rocky outcrop, where I could shelter from the wind for a while. I lay down on my back and listened to the Boyd’s Shearwaters filling my headphones with their brilliant calls (CD1-39). Just at that moment, it seemed they were as numerous as the stars. For some reason, the much more numerous Cape Verde Shearwaters were very quiet at this hour.

CD1-39: Boyd’s Shearwater Puffinus boydi Raso, Cape Verde Islands, 23:22, 22 March 2007. The evening peak of calling, 40 min after moonset. Most of the individuals are calling in flight. Background: Cape Verde Shearwater Calonectris edwardsii. 070322.MR.232201.11

At only 7 km2, Raso is similar in size to St Mary’s in Scilly, England. A sparsely vegetated, boulder-strewn plain of old lava, sand and small, dry streambeds forms the southern half of the island. In the north, the hills reach an elevation of 164 m. Although there are Boyd’s Shearwaters scattered all round the island, the greatest concentration is to be found in these hills.

Few birders spending the night on Raso have reported Boyd’s Shearwaters in recent years, perhaps because they visited on moonlit nights. Back in 1922 however, José Gonçalves Correia from the Azores, who was collecting for the American Museum of Natural History, found a “great population of them” on the island: “every night these birds fluttered and criss-crossed over their breeding grounds, chattering continuously” (Murphy 1924). When Mathews formally described Boyd’s in 1912, he named it after Boyd Alexander, the ornithologist we met before. During two separate expeditions, this Englishman had visited nearly all the islands and islets of the archipelago. The Raso Lark Alauda razae was his most important discovery (Donald & Brooke 2006), but from the hundreds of specimens Boyd Alexander collected in the Cape Verde Islands, no less than 11 new taxa were named in his honour (Hazevoet 1995). It was on Ilhéu de Cima, north of Brava, that he collected the type specimen of Boyd’s Shearwater in 1897:

“When the night shadows began to brood vaguely over this lone waste of an island, the petrels came abroad and filled the still air with their weird cries. They mustered strongly, flitting to and fro over the low-lying ground in hundreds. Among the number the most noticeable was Puffinus assimilis [the little shearwater], as it glided like some large soft-winged bat over the small sand hills, and even sometimes brushing past our camp fire, for ever uttering its weird cry ‘karki-karrou, karki-karrow, karki-karrou’… As the night wore on, the cries of these petrels died away, only to recommence, however, with redoubled energy just as dawn arrived, and then, as soon as the dusky light waxed clear, these voices ceased as suddenly as they had commenced, indicating that their owners had crept noiselessly into their dark retreats, there to remain till the heat had once more abated.” (Alexander 1898).

Magnus Robb, exploring breeding habitat of Boyd’s Shearwater Puffinus boydi, Raso, Cape Verde Islands, 22 March 2007 (Pim Wolf)

Alexander’s expeditions to the Cape Verde Islands were the first of many he was to make, but his life was cut short in 1910, during a foray into East Africa, when he was shot and clubbed to death by some locals, after refusing to go with them to see the local sultan (Mearns & Mearns 1988). Barolo Shearwater was described half a century earlier by Carlo Bonaparte, a nephew of the Emperor Napoleon, who gave it the scientific name baroli, after an Italian called Carlo Barolo.

On 13 February 2004, Arnoud van den Berg and I recorded Boyd’s Shearwaters in another part of the northern hills of Raso. On that night, we heard no other species of seabird at all. The roar of surf about half a kilometre away was muted to a whisper by features of the landscape, and a ridge sheltered us from the prevailing north-eastern wind. It was fantastically quiet, and the long, pregnant silences between calls made the sudden outbursts all the more dramatic (CD1-40).

CD1-40: Boyd’s Shearwater Puffinus boydi Raso, Cape Verde Islands, 13 February 2004. Presumed male and female calling in flight, with others heard calling in the distance. 04.003.MR.04020.11

We can assume that the higher pitched, purer sounding, slower callers are males, while the lower pitched, coarser and faster callers are females. In CD1-40, you can hear a male at 0:02, and a female at 0:13. Sexual differences along these lines have been proven in Barolo Shearwater (James & Robertson 1985c), and also in Audubon’s Shearwater (Trimm 2004). In Boyd’s, the reliability of sexing by voice has yet to be tested against other methods, and strictly speaking, it should be regarded as provisional.

Differences between the calls of Barolo and Boyd’s Shearwater can be found in pitch, timing and the number of exhaled notes. In both species, each five to seven second call consists of a repeating phrase of several exhaled notes (the second of which is often accented) followed by an audible breath note. As I listened on Raso, each phrase of Boyd’s seemed to contain fewer notes, which were delivered more slowly. When I compared them later, I noticed that the pitch of the inhaled breath note was lower in Boyd’s than for the corresponding sex of Barolo, typically by more than a musical semitone. Careful analysis of sonagrams has supported these observations. Statistical tests on the vocal data show that these differences between baroli and boydi are significant (George Sangster in litt). We can safely say that, on the whole, the sounds of these two taxa are subtly distinct.

Boyd’s Shearwater Puffinus boydi, female at night, clambering towards nesting hole, Raso, Cape Verde Islands, 14 February 2004 (Arnoud B van den Berg)

Whether individual birds can safely be assigned to one species or the other is more difficult to say. For example, would a vagrant Boyd’s Shearwater be reliably distinguishable by its sounds in a colony of Barolo Shearwaters? Most Boyd’s have three-note calls while Barolo typically has three, four, five or more exhaled notes in their faster calls. In my sample of 72 male and 24 female calls, only 31% of male Barolo had three-note phrases (and just 8% of females). However, none of these three-note callers had phrases more than a second long, while only 18% of male Boyd’s had phrases of less than a second.

I suspect it would be easier to pick out a vagrant Barolo in a colony of Boyd’s Shearwaters. Not one of the Boyd’s in my sample, male or female, had a five-note call. Among my Barolos, 26% of males and 62% of females had five or more exhaled notes, and one male even had eight. The number of notes is a character that can easily be assessed in the field. But it is important to listen to pitch and timing too. If a particular bird seems odd on all three points, then it would be sensible to make a sound recording, and to try to see the bird.

Boyd’s Shearwater Puffinus boydi, São Nicolau, Cape Verde Islands, 25 March 2007 (René Pop)

Identification of small shearwaters becomes much more tricky when the possibility of a vagrant Audubon’s Shearwater is considered. This third member of the North Atlantic clade looks very similar to Boyd’s Shearwater but is slightly larger and has pink feet. I have not had the opportunity to record Audubon’s, but William Mackin kindly supplied me with a set of recordings he made during his fieldwork, from which he has published measurements (Mackin 2004). Because most of his measurements were taken from calls in burrows, it would have been inappropriate to compare them with mine of Barolo and Boyd’s Shearwaters in flight. However, the impression I get from listening to his recordings is that Audubon’s has the same number of notes per phrase as Boyd’s but with shorter phrases and a faster delivery.

Most keen seawatchers in the Old World imagine that the nearest breeding Audubon’s Shearwaters are way over in the Caribbean, and come no nearer than New England, USA, outside the breeding season. But Audubon’s have been found breeding much nearer to the Western Palearctic than that. In fact they breed on the island of Fernando de Noronha, off the north-eastern coast of Brazil (Austin et al 2004), ‘only’ 2200 km from the Cape Verde Islands. This is roughly the same distance as from Madeira to the south-west of Ireland.

Boyd’s Shearwater Puffinus boydi, São Nicolau, Cape Verde Islands, 25 March 2007 (René Pop)

During our stay on Raso in 2007, there was a thin crescent moon above the horizon. While the moon was visible, only occasional calls could be heard. Each night the moon set a little later, and it was reassuring to note that vocal activity always peaked after the moon set. Sometime after moonset on the second night, I found a crevice in a cliff, which led to several Boyd’s Shearwater nests. Every now and then, a wave of vocal activity passed, then everything died down to complete silence again. As you can hear, calls given in the nest are quite variable, especially in their volume. In CD1-41, a powerful outburst can be heard at the start. This sounds so close and personal, you get the feeling you are actually in the burrow.

Boyd’s Shearwater Puffinus boydi, at night near nest, Raso, Cape Verde Islands, 22 March 2007 (René Pop)

CD1-41: Boyd’s Shearwater Puffinus boydi Raso, Cape Verde Islands, 23:24, 21 March 2007. Calls from nesting crevices, which are more variable than calls given in flight. Background: Cape Verde Shearwater Calonectris edwardsii. 070321.MR.232409b.00

In the same crevice, I could hear some very weak calls of a nestling, somewhere deep in the darkest recesses. In another nest nearby, under some jagged blocks of lava, I found a nestling that was quite easily visible from outside its nest. This was the same one that René Pop photographed a day later. Smaller than a tennis ball, it can hardly have been more than a few days old. In CD1-42, you can hear it communicating with one of its parents. First you hear the adult, then at 0:04 the nestling starts to call. There are short bursts of ‘rhythmic begging calls’, and the single notes separate from these are probably ‘long begging calls’ (Quillfeldt 2002).

CD1-42: Boyd’s Shearwater Puffinus boydi Raso, Cape Verde Islands, 01:19, 21 March 2007. Calls of an adult briefly at the start, followed by begging calls of a very young nestling, the one shown in the photograph. Background: Cape Verde Shearwater Calonectris edwardsii. 070321.MR.211908.01

Boyd’s Shearwater Puffinus boydi, nestling, Raso, Cape Verde Islands March 2007 (René Pop). The one heard in CD1-42.

From the tropical Cape Verde Islands to the Azores more than 20 degrees further north, little shearwaters breed in the same January to June period (Mougin et al 1992), and most Boyd’s

Shearwaters, it seems, hatch in the latter half of March. We found one or two other nestlings that had hatched too, and René saw an adult that was still brooding its single egg. Boyd’s, like Barolo Shearwater, are absent from the colony for only a short period at the end of the breeding season. As early as late August, Bourne (1955) found adults in moult on Ilhéu de Cima.

Boyd’s Shearwater Puffinus boydi, São Nicolau, Cape Verde Islands, 25 March 2007 (René Pop)

After three nights on Raso and one on Branco, we sailed back to São Nicolau. We had low expectations of seeing shearwaters during the crossing, because in the middle of the day we thought they would all be far out to sea. It was quite rough, so we sheltered from the spray under the cabin roof for most of the way back, watching one of the crew members gutting a series of small sharks they had caught. As we approached the leeward side of São Nicolau, the wind began to drop, and we clambered back up onto the bow. We had seen a couple of Fea’s Petrels P feae in this area on the way out, and almost immediately, one shot past at lightning speed, accompanied by whoops of excitement from all except René, who was having battery troubles. Just for a moment, he was not his usual cheerful self.

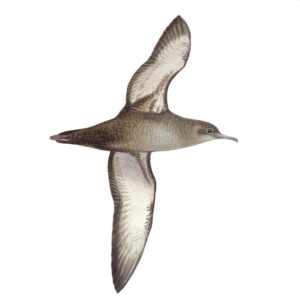

A couple of minutes later, René had replaced his batteries, and we were elated when he picked up a Boyd’s Shearwater feeding at very close range. None of us had seen one well at sea before, so this was a real bonus. The bird had a very particular way of foraging, spending most of the time with its wings spread, hanging just centimetres above the surface. It was clearly following something that we were unable to see, and sometimes it settled and ducked its head under the water, or dived for a second or two. After feeding near the boat for several minutes, it flew away with rapid wingbeats. When its wings took the full force of the wind, it sheared past the boat in small arcs, like a miniature Manx Shearwater. A few minutes later we had excellent views of another. The look of sheer delight on Killian’s face was priceless.

Boyd’s Shearwater Puffinus boydi, São Nicolau, Cape Verde Islands, March 2007 (René Pop)

We decided to hire the boat again the next morning, so we could spend more time in this area. In total we saw about 20 Boyd’s Shearwaters, sometimes feeding together on the surface in groups of three or more, nearly always using the same combination of low, slow flight, hanging in the wind, and short, shallow dives. Boyd’s and Barolo Shearwater both have relatively short wings for their size, making them efficient swimmers underwater (Warham 1990). Alexander (1898) observed that “at intervals one of them would disappear and swim after some small fish just underneath the surface of the water, after the manner of a Penguin”, and José Gonçalves Correia noted that when feeding “they spend much time below, sometimes emerging at a great distance from the spot at which they had disappeared” (Murphy 1924). Audubon’s Shearwaters are accomplished divers too; a male from San Salvador Island, Bahamas, reached a maximum depth of 46 m (Trimm 2004).

The amount of time spent near and below the surface may be one reason why Barolo and Boyd’s Shearwaters are so hard to find. Even when they are not feeding, they can still be difficult to see, because they tend to fly low in the troughs between waves. Neither species is thought to travel far, and Boyd’s has never been recorded in Europe. Away from its breeding grounds, Boyd’s has only been seen in small numbers off Senegal (Hazevoet 1997), and in 1976, one was trapped on St Helena, just south of the equator (Bourne & Loveridge 1978). A small shearwater found prospecting in a garden on Ascension Island in 2002 strongly resembled Boyd’s, although when a photograph was published on the internet (www.oceanwanderers.com), a whole range of alternatives were proposed. We hope that the illustrations, photographs and sounds in this book will help make the identification of Boyd’s less contentious in future.

Little shearwaters: known breeding distribution.

Recording locations indicated by arrows.

Barolo Shearwater Puffinus baroli (red dots).

Recordings: Ilhéu da Vila, Santa Maria, Azores.

Boyd’s Shearwater Puffinus boydi (green dots).

Recordings: Raso, Cape Verde Islands.

Audubon’s Shearwater Puffinus lherminieri (blue dot).

Only the colony closest to the Western Palearctic is shown; the main centre of distribution of this species is in the Caribbean.