Killian Mullarney

Text by Magnus Robb.

Barolo Shearwater Puffinus baroli is easily the most elusive shearwater in the North Atlantic. Not that this species is incredibly rare, although with just 3000 to 4400 pairs (Brooke 2004), it could hardly be described as common. Its population is twice that of Balearic Shearwater P mauretanicus, and yet Barolo is far more difficult to see. A typical view is from the rear, a tiny shearwater flying away from your boat as fast as its little wings will carry it.

During a recent pelagic trip with Killian in the Azores, Barolo Shearwater was, as usual, our most wanted bird. Towards the end of our second day out, we finally picked one up, flying away from us in travelling mode. We gestured wildly to our skipper Rolando, who immediately turned the inflatable and set off after it. The Barolo was beetling along at 60 km an hour. We know because that was how fast we had to go to keep up with it! Imagine the scene: shearwater glancing back over its shoulder and us trying in vain to keep camera and binoculars steady as we bounced over the waves. It was like something out of Wacky Races. The chase was brought to an abrupt end when our propeller hit a section of thick mooring rope that was floating on the high sea. Amazingly, we had another chance when a second chase began about five minutes later. At those speeds, it was amazing that Killian managed to get a presentable shot at all.

At night, Barolo Shearwaters can be pretty elusive too, and my quest to record them has been something of an initiation. In my previous life, before I had ever been to a petrel colony, nights were a time for sleeping. All this changed after I experienced my first Cory’s Shearwaters Calonectris borealis in April 2001, on Tenerife in the Canary Islands. Over the next few days, weeks and months, I embarked on a series of rather unsatisfactory nocturnal escapades, as I tried to work out how best to record some of the other species.

I knew that in the remote north-eastern corner of Tenerife, Bulwer’s Petrels Bulweria bulwerii were supposed to breed on an islet just 250 m offshore. I thought that, perhaps, Barolo Shearwaters might breed there too. When dusk fell, I followed the twisting road through the cloud forests on top of the Anaga peninsula, and down to the wild northern coast. In this corner of the island, the few settlements are small, and still largely untouched by tourism. A narrow dirt track snaked along the steep, rocky coast towards the tip of the peninsula. I followed it as far as I could, then parked at the last point where I could turn the car. A ghostly, pyramid-shaped islet glowed in the light of the full moon, about a mile further along the coast. Very few creatures were on the move. Geckos darted between the rocks, and rustling betrayed an occasional rodent. After nearly an hour’s walk in a vivid moonscape, I clambered down rocky slopes to the shore. The islet was so close, I even considered swimming out to explore it. Nothing moved but the surf, and no sound disturbed its gentle white noise. If any petrels or shearwaters were calling over the Roque de Tierra, I was unable to see or hear a single one.

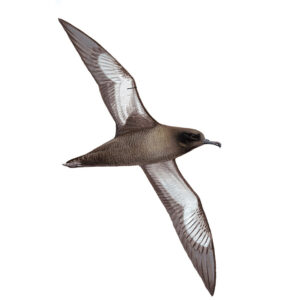

Barolo Shearwater Puffinus baroli, south-east of Graciosa, Azores, 27 May 2007 (Killian Mullarney)

The next night, I tried the viewpoint of La Quinta near the town of Santa Ursula. It turned out to be a high sea cliff topped by recently built holiday villas, most of which were empty. Their excess concrete had dried while spilling over the edge. I flushed a Barn Owl Tyto alba from the roadside. It landed in a nearby pine tree and hissed at me. Beyond the reach of the streetlights, I found some undeveloped ground, where I was able to listen for sounds from the cliffs below. I could make out some white patches in the moonlight, hinting at the locations of nests, but only a single Cory’s Shearwater called way down beneath me. Building activity might have disturbed this colony, or was there some other reason for my poor luck? April should have been a good month to hear Barolo Shearwaters, so I tried one more site. José Manuel Moreno (2000) had made close-up recordings at La Guancha, a newly discovered colony of some 20 pairs. In the western part of the northern coast, I found a town of this name. Some cliffs nearby looked suitable, but my attempt to hear Barolo here was also in vain. So what was I doing wrong?

Four months later, Roy Slaterus and I obtained permission to visit a Barolo Shearwater colony during a visit to Madeira. Thinking the problem on Tenerife had been not knowing exactly where to look, I was confident we would be successful this time. Ilhéu do Farol, an islet at the end of the Ponta de São Lourenço, was only a few hundred metres long, so displaying Barolos could never be far out of earshot. It turned out to be an excellent location for Bulwer’s Petrels and Madeiran Storm Petrels Oceanodroma castro but still not a single Barolo was heard, here or at Ponta do Garajau, another Madeiran site where they have been heard in the past (van den Berg & de Wijs 1980). By now this bird was becoming something of an obsession.

I had another try in early April 2002, when I visited Santa Maria, the most southerly island in the Azores. This island has a kinglet all of its own, Regulus azoricus sanctaemariae, my main target bird for the visit. I was also very interested in the islet called Ilhéu da Vila, about 300 m offshore, which has a colony of Barolo Shearwaters. At 50 pairs, it is one of the largest of the 30 or so colonies in the Azores (Monteiro et al 1996a, 1999). Towards the end of the day, I walked round as near as I could get to the islet. The skies were full of displaying terns that had just returned from their wintering grounds, not yet ready to reclaim their nests. Beyond the islet, rafting Cory’s Shearwaters waited to visit their burrows after dark. The light was fading, but I thought I could see some much smaller silhouettes flying in to join the Cory’s. An hour later, the islet had vanished under a raven-black sky. I was elated when the wild, high-pitched laughter of distant Barolo Shearwaters drifted across the channel.

The lady who served me breakfast next morning was married to a fisherman, who could take me to Ilhéu da Vila for a small fee. When I asked about permission to land, I was directed to the office of the local capitania. A week or two later he would have forbidden a visit, because of the important tern colony, but for now I was allowed. Later, I learned that I should have asked the Azorean environmental protection authorities. The fisherman agreed to take me to the islet before dusk in a rowing boat, then pick me up again around midnight. Landing involved a leap onto the rocks but fortunately, the weather was calm. I still had time to find the highest concentration of burrows before dark, while recording Roseate Terns Sterna dougallii displaying out over the sea. At 19:21, while Common Quails Coturnix coturnix announced the end of the day, a new lunar month began.

Roseate and Common Terns S hirundo chased each other over the sea into the night, soon to be joined by a chorus of Cory’s Shearwaters. An odd caller among them had me scratching my head. I suspected it of being a Madeiran Storm Petrel, but later it turned out to have been my first Sooty Tern Onychoprion fusca- tus. It was not long after dark when the Barolo Shearwaters joined the party. In the area with the highest density of nests, the ground pulsated with their calls. Others flew invisibly back and forth over the colony (CD1-35). In the pitch blackness of new moon, they were throwing all their inhibitions to the wind. I was enjoying this unique soundscape so much, it took me a while to realise that I had been jinxed once again. When I could no longer resist having a look, I discovered I had forgotten my torch.

This time, however, the Barolo Shearwaters were not going to have the last laugh. To share the elation of recording them at last, I called fellow Sound Approach recordist Mark Constantine. With the help of a pair of Barolos down a burrow, I left him his best voicemail ever. I hope he has forgiven me.

CD1-35: Barolo Shearwater Puffinus baroli Ilhéu da Vila, Santa Maria, Azores, 12 April 2002. Male and females calling in flight, on a dark night of maximum activity. Background: Cory’s Shearwater Calonectris borealis 02.016.MR.04113.31

So the puzzle was solved; when the moon is away, the shearwaters play. Since my visit to Ilhéu da Vila, I have always tried to visit shearwater colonies at new moon, and I am rarely disappointed. Even late in the breeding season, I have enjoyed surprisingly good results. If new moon finds me working at home, I am itching to visit remote islands. When the moon waxes and the nights get brighter, calling wanes and I can relax. Barolo Shearwater can turn a birder into a bit of a lunatic.

Most petrels limit their breeding activities to the hours of darkness, so I should have been quicker to realise they prefer to call on the darkest, moonless or overcast nights. Several species have been shown to arrive later on well-lit nights, when it takes longer for light levels to drop below a critical level (Brooke 2004). Among these is Audubon’s Shearwater P lherminieri (Trimm 2004), a close relative of Barolo Shearwater which breeds from the Caribbean to north-eastern Brazil. On Røst in the Lofoten islands, Norway, Leach’s Storm Petrels O leucorhoa go to much greater extremes. Because of the midnight summer sun, they delay laying until late August or even September (Anker-Nilssen & Anker-Nilssen 1993). Given 41-42 days incubation, and a fledging period of 63-70 days (Cramp & Simmons 1977), their young may not fledge until the winter solstice, when there is no daylight at all. When colonies are less strictly nocturnal, the importance of the moon is reduced. Among the crepuscular Cory’s Shearwaters breeding on Selvagem Grande, Selvagens, moonlight has no effect on activity, hour of arrival at the colony, or the time spent inside the burrow (Granadeiro et al 1998a). Non-breeders, however, visit the colony less frequently at new moon (Bretagnolle 1988).

Magnus Robb, trying to record Boyd’s Shearwaters Puffinus boydi on a moonlit night when he should have known better, Santo Antão, Cape Verde Islands, 24 February 2007 (Ilse Schrama)

Predation risk is usually thought to explain the preference for darkness in so many petrels. On high-latitude islands, they often fall prey to gulls and skuas, which hunt by sight long after sunset. Slaty-backed Gulls Larus schistisagus hunt for Leach’s Storm Petrels at night on islands off Hokkaido, Japan. On moonlit nights in May and June, fewer petrels visit, arriving later after sunset, but in August and September they seem unaffected by the moon. May and June are months when predation by the gulls is relatively high, but the risk becomes lower as the summer progresses and the gulls finish breeding (Watanuki 1986). On Kerguelen Island in the southern Indian Ocean, Brown Skuas Stercorarius antarcticus prey heavily on Blue Petrels Halobaena caerula at night. Mougeot & Bretagnolle (2000) removed all prey remains from nine skua nests every morning from October 1992 to March 1993. When the full moon was not obscured by clouds, the skuas caught about three times as many petrels as they did at new moon. This was despite precautions taken by the petrels, which called much less on moonlit nights.

Unable to find nocturnal predators in colonies around northern New Zealand, Imber (1975) developed another theory to explain why fewer petrels visited on moonlit nights. Many feed on bioluminescent creatures such as krill and squid that migrate from the depths to the surface at night. How close these come to the surface, and to the reach of petrels, depends on light levels, and is thus affected by the state of the moon. At new moon, feeding conditions are best, while at full moon, despite better visibility, food is harder to find. Imber reasoned that well-fed petrels at new moon can more easily afford to visit the colony, but they will continue to look for food when the moon is full. Squid is an important food for Barolo Shearwater too (Monteiro et al 1996b), so nocturnal foraging may be one reason why the moon affects this shearwater so strongly.

Barolo Shearwater was included in a study of the effect of the moon on the petrels of Selvagem Grande (Bretagnolle 1988). Vocal activity in Barolo normally peaked at the start of the night. However, if the moon was present at this time, vocal activity was practically nil, and the concert was delayed until after moonset. “When there is no moon they call continuously, but the moment the moon rises or if a bright torch is shone into the area vocalizations cease” (Zino & Biscoito 1994). Smaller species tend to be the ones most strongly affected by moonlight, probably because they are more vulnerable to predation. On Selvagem Grande, Yellow-legged Gulls L michahellis mainly feed on smaller petrels (Bretagnolle 1988), so predator avoidance is likely to be the main reason Barolo prefers the dark.

Shearwater colonies at full moon are not necessarily devoid of birds. Breeders need to incubate eggs and feed their young, so they may come into the colony without calling. This is exactly what a Canadian study found in a colony of Manx Shearwater P puffinus (Storey & Grimmer 1986). Non-breeders are more strongly affected by moonlight. They spend more time above ground and are thus more exposed to danger. Not having any duties, they can more easily afford to skip a few nights around full moon, and studies have shown that this is exactly what they do (Bretagnolle 1988). This may also allow them extra foraging time on well-lit nights, when food is harder to find.

I now started to wonder, could the moon influence movements of vagrant Barolo Shearwater along the coasts of northern Europe? Should seawatchers revere the dark side of the moon? When I asked Killian if he had ever seen a Barolo in Ireland, it turned out he had found his only one while seawatching at the Bridges of Ross, Clare, on 25 August 1995, during what must count as one of the most gripping European seawatches of all time. Besides the Barolo, they saw 11 Cory’s, 9 Great P gravis, 9 Balearic P mauretanicus as well as the usual Manx and some Sooty Shearwaters P griseus. Not to mention a Fea’s-type petrel Pterodroma and a Wilson’s Storm Petrel Oceanites oceanicus, with a supporting cast of a Leach’s Storm Petrel, countless British Storm Petrels Hydrobates pelagicus, 4 Long-tailed Jaegers S longicaudus and 13 Sabine’s Gulls Xema sabini. The next day, seawatching in the west of Ireland continued to be excellent with, for example, two further sightings of Fea’s-type petrels in Kerry. In fact, the whole period from 24 to 28 August 1995 was considered exceptional (Dempsey 1995). When I looked up the lunar tables, it turned out that new moon was right in the middle, on 26 August.

Was this coincidence? A handy list of other contenders for ‘best seawatch of all time’ is not available, but I do have the dates of the other 13 accepted Irish records of Barolo Shearwater. When I checked them against the lunar tables, no clear pattern emerged. The chances of seeing a Barolo during the less moonlit half of the lunar cycle were no greater than during the more moonlit half. Other effects such as weather, weekend bias and the late August peak in seawatching make it difficult to assess the importance of the moon. In August 1995, new moon not only coincided with the most popular seawatching weekend of the year, but also with the first good blow of the autumn.

In 1981-82, a Barolo Shearwater visited the island of Skomer, Wales. It was discovered by Paul James, who was studying petrel sounds at the time (James 1986). He first heard it on 26 June 1981, five nights before new moon, dismissing it as a Eurasian Oystercatcher Haematopus ostralegus, until he noticed the sound was coming from underneath a boulder. When he moved some rocks and saw a bit of a shearwater, he assumed it was an odd-sounding Manx Shearwater, and left it at that. Three nights later, hearing the sound again, he realised it was very different from the Manx that could be heard flying all over the island. The mystery bird was caught quite easily at the edge of a pile of boulders. Half the size of a Manx, with pale blue legs, it had to be a Barolo. For several nights it continued to be heard, calling in flight or from its burrow. Sound recordings were made on 1 July, the night of the new moon. By the time the bird was ringed on 7 July, it had furnished its burrow with a little vegetation. On 10 July, a day after first quarter, it was heard for the last time that year.

At new moon in June 1982, the next year, seabird workers on the island were delighted when the same ringed bird turned up again. It was subsequently heard calling during most nights of the next new moon period in July. On 3 May 1983, with the moon approaching last quarter, a different, harsher-sounding Barolo Shearwater was heard on Skomer. Its calls were not recorded, and to the best of my knowledge, only one Barolo has been heard calling in Britain or Ireland since.

To continue their work on petrel sounds, Paul James and Hugh Robertson visited the Selvagens in July 1983. Among other things, they discovered that the voice of Barolo Shearwater is sexually dimorphic, something that was already known for Calonectris and Manx Shearwaters. Following the usual pattern, males had clearer, higher-pitched voices, while females sounded lower and harsher (James & Robertson 1985c). This made it possible to sex the two Barolos heard on Skomer retrospectively. The one with the oystercatcher-like voice in 1981 and 1982 was a male, and the less musical one in 1983 was a female.

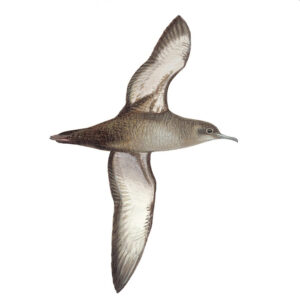

Barolo Shearwater Puffinus baroli, Ilhéu da Vila, Santa Maria, Azores, 27 August 2003 (Elena Gómez-Díaz). Taken in the breeding colony where CD1-35 to CD1-38 were recorded.

When I visited Ilhéu da Vila, in the Azores, I found it fairly straightforward to tell the difference between male and female calls. In CD1-36, you can hear an example of two males calling in flight. The next track, CD1-37, begins with a prominent female, followed by a couple of more distant males. Further females can be heard at 0:21 and 0:43. The difference between males and females is not just a question of pitch and harshness; female calls also average shorter and tend to have more notes, resulting in a more hurried delivery. When I measured 72 male and 24 female call phrases in sonagrams, female phrases turned out to be 6% shorter, with an average of 4.9 exhaled notes, as opposed to 4.2 notes in males.

CD1-36: Barolo Shearwater Puffinus baroli Ilhéu da Vila, Santa Maria, Azores, 27 June 2006. Two males calling in flight. Background: Cory’s Shearwater Calonectris borealis. 02.016.MR.03945.00

CD1-37: Barolo Shearwater Puffinus baroli Ilhéu da Vila, Santa Maria, Azores, 12 April 2002. Calls in flight, with prominent females at the start, then at 0:21 and 0:43. Background: Cory’s Shearwater Calonectris borealis. 02.016.MR.03604.01

In CD1-38, you can hear both male and female Barolo calling in their burrows.

CD1-38: Barolo Shearwater Puffinus baroli Ilhéu da Vila, Santa Maria, Azores, 12 April 2002. Several males and females calling from their burrows. Background: Cory’s Shearwater Calonectris borealis. 02.016.MR.04713.00

The faster tempo of the harsher females is striking. Female calls are shorter and faster in most Puffinus shearwater species (Warham 1996). These include Great (Brooke 1988), Sooty (Warham 1996), Short-tailed P tenuirostris, Manx (James 1985a), Balearic (chapter 6), Yelkouan P yelkouan (Bourgeois et al 2007), Audubon’s (Trimm 2004) and Tropical Shearwaters P bailloni (Bretagnolle et al 2000). On the other hand, male and female Calonectris shearwaters seem to show little if any difference in call length (Bretagnolle & Lequette 1990). Perhaps there is no need, because the contrast in their frequency and timbre is already so extreme.

One of the reasons so little is known about Barolo Shearwater may be that breeding ends when the summer fieldwork season begins. On Selvagem Grande, laying takes place in January and February, hatching in March and April and fledging in May and June (Mougin et al 1992). The very last juveniles leave between 22 and 30 June (Jouanin 1964). So when Killian and I visited Selvagem Grande on the night of 27/28 June 2006, the timing for our most wanted species was rather poor. The two or three Barolos we heard that night were a tiny fraction of a population estimated at more than 1000 pairs (Zino & Biscoito 1994). Had it not been for the new moon, we might have heard none at all.

Moulting adults can be numerous on the island in July (Jouanin 1964), when there can be quite a respectable chorus, but we were a little too early to hear this. From July onwards, calling is probably heard on most dark nights at the colony, until the next breeding season starts in the winter. It is curious that the Skomer male, which was not in moult, was found almost 25 years to the day before our visit to the Selvagens. I now realise that this is about the least likely time of year for a Barolo Shearwater to visit land. Probably, it was attracted by the din of the 100 000 or so pairs of Manx Shearwaters breeding on the island, which would have peaked at the June new moon.

At the southern limit of the Western Palearctic, Boyd’s Shearwater P boydi of the Cape Verde Islands has served as a taxonomic shuttlecock ever since Mathews first described it as “a puzzling race” back in 1912. It has been knocked back and forth continuously between ‘Little Shearwater’ and ‘Audubon’s Shearwater’, two messy ‘polytypic species’ with up to 40 ‘subspecies’ assigned to them.

Little shearwaters: known breeding distribution.

Recording locations indicated by arrows.

Barolo Shearwater Puffinus baroli (red dots).

Recordings: Ilhéu da Vila, Santa Maria, Azores.

Boyd’s Shearwater Puffinus boydi (green dots).

Recordings: Raso, Cape Verde Islands.

Audubon’s Shearwater Puffinus lherminieri (blue dot).

Only the colony closest to the Western Palearctic is shown; the main centre of distribution of this species is in the Caribbean.

A recent DNA study of the smaller shearwaters has started to clear things up (Austin et al 2004). It shows that Boyd’s Shearwater belongs to a distinct North Atlantic group, along with Barolo Shearwater and ‘the original’ Audubon’s Shearwater P lherminieri, which breeds from the Caribbean to north-eastern Brazil. This North Atlantic group is less closely related to the small shearwaters of the southern, Indian and Pacific Oceans than previously thought.

Barolo and Boyd’s Shearwaters are not only geographical neighbours, but also each other’s closest relatives. Boyd’s is diagnosably distinct, and has already been elevated to species status by some authorities (eg, Hazevoet 1995). The BOURC taxonomic subcommittee (Sangster et al 2005) decided not to split Barolo and Boyd’s for the time being, “pending study of recently collected sound recordings”. Now you can listen to the recordings in question, which were made on Raso, Cape Verde Islands, on 13-14 February 2004 and supplemented on 20-23 March 2007.