Chapter 3: Marooned

Sometimes on pub night I’ve suggested that it would be interesting to know more about what is going on under the water. This has never been greeted with much enthusiasm. I’ve also tried chatting to the fisherman to try and find out which fish like to hang out where. Not that they are keen to part with their secrets. Botanists are more forthcoming, but they mostly want to talk about Spartina, whether it’s decreasing and by how much. Botanist John Mansell-Playdell found the first small clump of what was then an unusual cord grass at Ower on 17 July 1899. It was S x townsendi, a hybrid between a local cord grass and an American immigrant, and he thought it may have arrived, like other alien plants, on the bottom of transatlantic boats (Humphreys & May 2005). It was a botanical rarity until August 1907 when it appeared in “hundreds of spots”. The roots were able to attract and hold together the silt, and by 1924, nearly a third of the harbour’s intertidal areas were covered in this short green grass. It was great for breeding Redshank, but it also provided firmer ground for the hunters and their dogs.

One strictly underwater plant was the eelgrass Zostera, which formed meadows grazed by Brent Geese and Wigeon. While Spartina was changing the appearance of the harbour, the eelgrass was dying out. By 1925 it had almost completely disappeared, not just locally but throughout the whole of the North Atlantic. A parasitic microorganism was thought to be responsible. The combination of shooting and the disappearing eelgrass decimated the Brent Geese and by the ‘60s, Alan Bromby of Brownsea Island could write that he was only counting “up to four Brent Geese in the harbour during January and ten there on 27th December” (Bromby 1963). By 1966, they were no longer regular visitors, only being recorded in twos and threes on odd occasions (Dixon 1966).

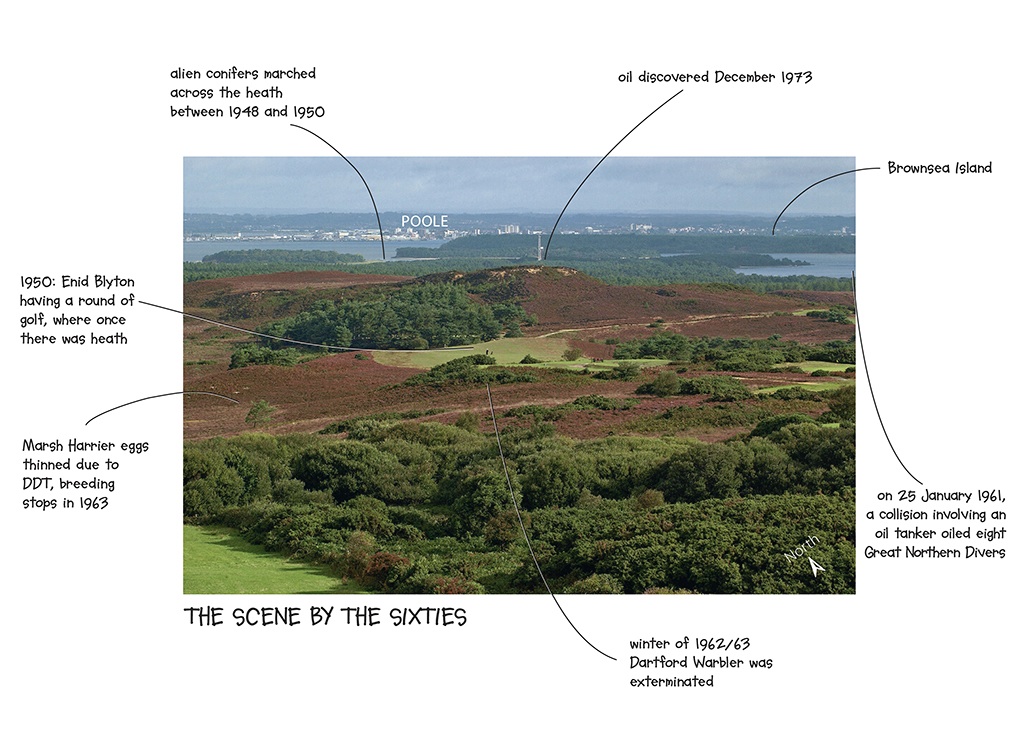

Rempstone heath and Enid Blyton golf course, Dorset, 24 August 2004 (René Pop). Looking north from Studland heath viewpoint.

Many other birds were considered a nuisance or just fair game. Crows were routinely poisoned, and the local Ravens that had been at Corfe for centuries finally vanished. Rooks were barely tolerated, and their young were taken annually. Even Barn Owls were shot and stuffed, as were any scarce or rare birds. Thomas Hardy made numerous references to Dorset bird-catchers snaring and selling wild Goldfinches, Bullfinches and Yellowhammers. Bird feathers in hats, and bird skins as clothes were routine.

I would have hated seeing all this carnage and capture, and I despise the argument that landowners will only look after the wildlife on their land if it has a commercial purpose. The RSPB was in its infancy, having been started as The Plumage League by Emily Williamson and a group of ladies as an anti-plume hunting activist group. In 1927, Mary Bonham-Christie, a radical pioneer who hated cruelty to animals, bought Brownsea Island. Wanting absolutely no human interference at all, she proceeded to evict all the islanders. The island’s population that had stood at 270 in 1881 was down to just five in 1961.

Popular English children’s writer Enid Blyton immortalised Bonham-Christie’s Brownsea for children, when she called it ‘Keep-Away Island’ (Blyton 1962). Even the scouts, whose founder Baden Powell had organised their first camp on Brownsea in 1907, were banned. Bonham-Christie is reported to have said of them, “I many times stopped them ill treating without cause older people’s dogs and cats, stealing the eggs from the nests of birds and killing with a catapult birds in trees” (Moore 2003). (Mo was in the guides in the ’60s, and can remember the girls’ outrage at seeing boy scouts catapulting birds.)

Unsurprisingly, Bonham-Christie’s actions created resentment, and when the last family was finally evicted a fire was started that raged across the island for three days. This was bad news for the several pairs of Dartford Warblers on the island, although changes in pesticide use in Dorset gave them more serious problems. Chemical fertilisers and pesticides were replacing the tons of horse dung, and this enabled heath to be ‘improved’ to create Studland golf course, for example, which was owned by Enid Blyton and her husband, and Greenlands farm below it.

I was at school while this was going on. Enid Blyton’s books were frowned upon there, while Shakespeare was encouraged. I remember auditioning for The National Youth Theatre by reading the scene in Macbeth where the forest of Birnam marched on Dunsinane. Something similar happened here when fertilisers enabled foresters to plant conifers across our heathland. Between 1948 and 1950, pines advanced across 5000 acres of heath all around the golf course, covering an area from Corfe Castle to Goathorn and only stopping at Greenlands farm. The concept of forest renewal was also taught at our school, although the birdsong-filled Scots Pines, oaks, elms, limes and alders our forefathers had been removed were now being replaced by silent rows of Corsican Pines. While some birds like Siskin, Coal Tit (CD1-07) and the various vocal types of crossbill increased, on the whole you visited a commercial pine forest for silence. By the ‘60s, two thirds of Dorset’s heathland had gone. Dartford Warblers were now in serious decline.

CD1-07: Coal Tit Periparus ater Rempstone, Poole Harbour, Dorset, England, 10:11, 30 March 2008. Song of two rival males in a Corsican Pine plantation, with very high rattling calls heard frequently in the second half of the recording. Background: Common Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs. 080330.MR.101100.01

At that time all the estates around the harbour employed gamekeepers, so birds of prey were routinely snared or poisoned and hung nearby to show diligence. Egg collecting was a popular hobby, and in the ‘50s the heaths were a favourite destination for amateur birdwatchers searching out nests and taking home an egg or two. Ilay Cooper’s Purbeck revealed (2004) contains his memories of birds and birding in the harbour. Children were far more active then, and he tells a tragic story about himself and a friend clambering, aged 14, over the cliffs a little short of Ballard Point. He and Keith MacDonald used to go out along the cliffs looking for gulls’ eggs or simply birdwatching. On one expedition when Keith had climbed down at the highest stretch of cliff, “The large piece of rock which he was gripping gave way and he fell to his death.”

Fortunately, not all children’s adventures ended this way. In 1943, the children from Bryanston School Natural History Society recorded three sightings of a female or juvenile Marsh Harrier at Swineham. At the time, there had only been three records in the past 40 years. Three years later a male was seen carrying reeds, and in 1949 the first signs of breeding were observed at Keysworth. By 1954, five pairs were breeding in the harbour at Little Sea, Keysworth, Middlebere, The Moors and on ‘Keep-Away Island’. Up to 22 adults and 12 young were seen that year. Sadly, by 1963 breeding had stopped. It was thought that human intrusion, egg collecting, shooting, and flooding of nest sites caused a decline from which the birds never recovered, then fragile eggs caused by the toxic pesticide DDT dealt the final blow.

Cooper (2004) describes another catastrophe that happened on 25 January 1961, when there was a collision at the harbour entrance during gale force winds. The harbour was full of birds when two ships collided… “one carrying red paint the other carrying blue paint. Apparently, all the seamen were marooned,” commented Nick while helping with the text. He was finding all this doom and gloom a little depressing. If you also think the story is a little too Shakespeare and not at all Enid Blyton don’t worry. There are only a couple more pages to go before it cheers up.

Sadly, then, it wasn’t colourful paint but a mass of crude oil that was spilled, and the shore was littered with oiled birds, dead and dying. “We caught what we could,” writes Cooper. “In our warm kitchen my mother tolerated two guillemots, two black-necked grebes, a great northern diver and a little purple sandpiper. Part of an organised survey, we patrolled the shore, marking each dead beak with red nail polish to avoid double counting.” The whole of the area south of Brownsea Island was covered in oil, as were 300 birds of 32 different species. Worst were 10 dead and eight oiled Great Northern Divers.

Then came the worst winter weather for 223 years. 8 cm of snow fell on 26 December 1962, with a further 23 cm three days later, this time accompanied by northeast gales. These blizzards piled snow into 2-3 m deep drifts, and in some exposed places it was 6 m deep. The thaw was a long time coming. January and February were dominated by heavy frosts, allowing the snow to remain intact for a further 70 days, with most lasting until 6 March.

“Bitterns and Woodcock were reported dead or dying in an emaciated state and in areas close to houses where they would not normally be seen. Black-tailed Godwit and Redshank seem to have suffered the heaviest losses… Victims of the freeze up include many Shelducks”, wrote county recorder J C Follett (1963).

H G Alexander (1974) takes up the tale. “The most extraordinary assemblage of waders was found by Trev Haysom and myself on the three-mile-long sandy beach to the north of Studland on 7th February. The frost had gone so deeply into the sea that masses of razors and other shell-fish from the shallow seas had been frozen and thrown up dead all along the beach. This had attracted crowds of gulls and waders. The gulls we reckoned at approximately 5000; the waders at 2000.” In the Bird report for 1963: “Goldcrest complete or almost complete absence …Wren drastically reduced in all areas…Stonechat numbers considerably reduced.” Dartford Warblers were thought to be down to four pairs for the whole of Dorset.

These were desperate times. DDT had been replaced by a new range of chemicals: organochlorides like dieldrin, aldrin and heptachlor. They were very effective at eliminating fungi from grain, moths from cloth, and scourge from sheep. Unfortunately they drained from the fields into the watercourses and up the food chain to fish and eels. In this way they also killed otters and herons. Pigeons and pheasants that ate the grain were also poisoned, along with the foxes that predated them. Among the most obvious victims were the local Peregrines. I remember reading in 1973 of a leading local environmentalist and broadcaster Kenneth Allsopp, who died of a drug overdose after writing for the Sunday Times on the loss of the last breeding Peregrines in Dorset.

Peregrine Falcon Falco peregrinus, Old Harry Rocks, Ballard Down, Dorset, 17 November 2009 (Nick Hopper). ‘This species was the most obvious victim of organochlorides in the ‘60s.’

Chemical manufacture in Britain had its beginnings in Poole, with alum and copperas for ink being produced at Evening Hill. Now it had moved into the centre of town, on the edge of the harbour. I had a conversation with the man who was responsible for maintaining the pumping equipment at this local chemical works. He told me that in the ‘60s, the hydrochloric acid would corrode the pipe work and hundreds of gallons would regularly leak into Holes Bay. Years later, the chemical works blew up on a pub night and 2,500 people were evacuated. A passing van shot into the air, traffic lights melted, the blast blew a man off his bike and I could see chemical drums hurtling through the air. Anglers three miles out to sea were splattered. We postponed the pub to the following week, and the chemical works moved inland.

Back in April 1961, Mary Bonham-Christie died aged 98, and things looked bleak. Shooting syndicates prepared to buy Brownsea Island, while her son applied for permission to build 400 houses there.

Poole’s birds needed protection. Thankfully help was at hand, and although many conservationists helped to save the day, three clear heroes emerged.

One of them was birder Helen Brotherton. In 1961 she became the secretary of the appeal to save Brownsea. Arguing in favour of its qualities as a nature reserve, she was part of a small team who defeated the housing suggestion and persuaded the nation to take Brownsea in lieu of Bonham-Carter’s death duties, giving it to the National Trust. Helen also helped start the Dorset Naturalists’ Trust, which took over the management of the lagoon and a third of the Island. When Arne came up for sale, Brotherton alerted the RSPB, liaising and encouraging them into buying the peninsula and setting up the first Dorset RSPB reserve in 1966.

The second was renowned amateur conchologist Captain Cyril Diver, who was also clerk to the financial committee of the House of Commons. In both roles, he had a reputation for being thorough and coping with a lot of detail. Diver made two painstaking ecological surveys of Studland during the ‘30s. He wrote a detailed paper that led to the creation of The Nature Conservancy (Diver 1947), and then he became its first director general.

The third was Ralph Bankes, who inherited the Bankes estate and in the tradition of eccentric landowners, lived in just three rooms of Kingston Lacey, the family’s stately home. His son John Bankes lived even less ostentatiously in Fulham. The estate was vast at over 8,000 acres, and included 12 working farms, Corfe Castle, all of Studland, the Ballard peninsula, the harbour shore at Middlebere and the Purbeck Hills, in other words many of the best birding sites. In 1954, Diver and Bankes made Hartland Moor one of the first National Nature Reserves, starting a series of reserves and alliances that were to encircle the harbour. They then went on to create what was described at the time as Britain’s second largest reserve out of Studland peninsula, which Diver’s own intimately detailed studies had certainly shown had some of the highest biodiversity in Britain. Ralph Bankes became ill, and his son John seemed poorly qualified to run the estate, so in 1981 Ralph bequeathed it all to the National Trust. It was a massive gift. John Bankes died in 1996 and lies in Studland churchyard.

James Lidster, in hide at Middlebere Farm, Middlebere channel, Poole Harbour, Dorset, 24 August 2004 (René Pop)

In 1981 Holton Heath was added to the protective ring around the harbour, when Diver made it a National Nature Reserve. All these reserves form a substantial area of habitat managed for wildlife. Today this combination of heath and wetland makes Poole Harbour the most important natural area in the county, and happily it also ranks as one of the most successfully conserved areas in Britain. The birds have never had it so good, at least not in the last 150 years, and the birding has got so much better. In CD1-08, you can hear a typical scene at one of our favourites among the places protected by the likes of Bankes, Brotherton and Diver.

CD1-08: Middlebere at dawn, Poole Harbour, Dorset, England, 04:54, 14 May 2010. Canada Goose Branta canadensis, Common Pheasant Phasianus colchicus, Water Rail Rallus aquaticus, Common Wood Pigeon Columba palumbus, Common Cuckoo Cuculus canorus, Eurasian Wren Troglodytes troglodytes, Common Blackbird Turdus merula, Song Thrush T philomelos, Eurasian Reed Warbler Acrocephalus scirpaceus, Common Whitethroat Sylvia communis, European Blue Tit Cyanistes caeruleus, Common Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs and European Goldfinch Carduelis carduelis. 100514.MC.045400.01

If you have been wondering what a conchologist does, Captain Diver was really keen on snails, well, snails and taxonomy. He made a study of the snails in the trenches while on active service in the First World War and on his return was considered an authority on the importance of fossil records for geneticists. He was also an expert on sinistrality, the way snails with left handed whorls on the shell cannot mate with those with right handed whorls. Had he been alive today he would have known that this difference has come down to a single gene and is the basis for much of modern taxonomy.