Chapter 4: If that’s a Bibby’s Warbler I’ll eat my hat

Killian Mullarney

After researching the first chapters I asked the fellows down the pub the big question. Why isn’t the English Dartford Warbler a species? We’ve been able to see how Dartford Warblers arrived in what is now Poole Harbour between 9,000 and 7,000 years ago as a warming climate pushed the ice back. Perhaps they came up the Atlantic coast with Nick’s ancestors from a refuge in Spain or Portugal. As his ancestors cleared the trees, the Dartford Warblers exploited the resulting heathland.

Then came the formation of the English Channel, effectively stranding these non-migratory birds. On their isolated northern outpost, they became exposed to a fluctuating climate, facing some serious challenges during the colder spells. However, right up until the 1900s there was no shortage of habitat. Maps from around 1750, show that the Poole area was covered in heathland, and in the warmer periods the population would have reached a peak. It must also have been these same large amounts of suitable habitat that enabled them to survive the cold periods.

Bournemouth and Poole expanded, and modern pesticides and fertilizers enabled the local heath to be ‘improved’ into farmland, commercial forests and golf courses. By 1960, two thirds of our heathland had gone. The depleted Dartford population struggled to survive. After the seriously cold winter of 1962/63, there were thought to be just four pairs for the whole of Dorset, all on the fringes of Poole Harbour.

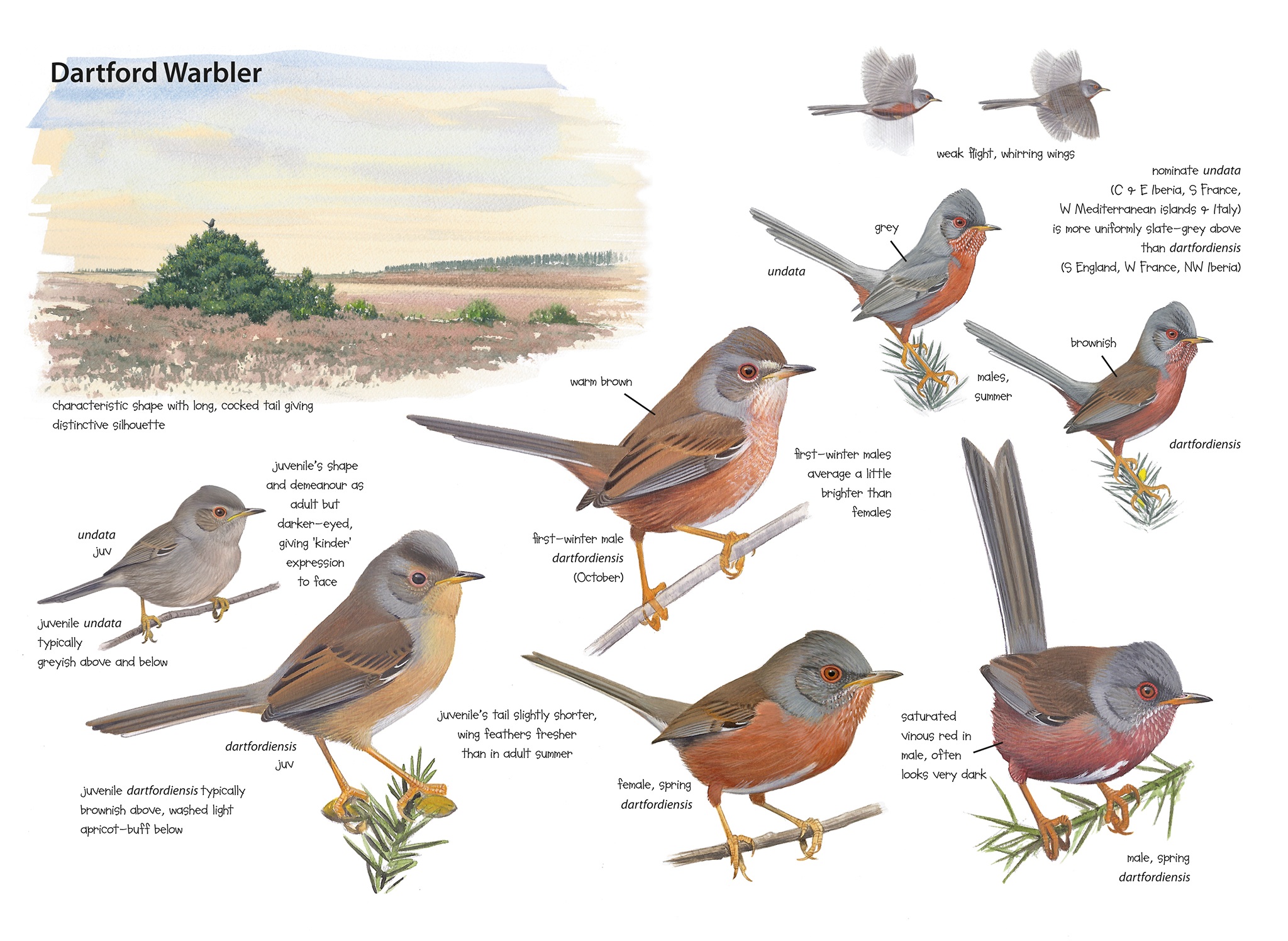

It is generally accepted that there are three subspecies of Dartford Warbler. Dartfordiensis is the one we have in England, the largest group, undata is found in the rest of southwest Europe, from about halfway down through France, and the third, toni, is found in North Africa. However, in a recent monograph on the Sylvia warblers (Shirihai et al 2001), a detailed analysis of Dartford Warbler skins from museums throughout Europe struggled to establish exactly where the ranges of the three subspecies of Dartford Warbler began and finished.

Dartford Warbler is closely related to Balearic Warbler and slightly more distantly related to Marmora’s Warbler. The common ancestor of all three split from Spectacled Warbler just over five million years ago, around the time when the waters of the Mediterranean returned after a long period of drought, creating many of the islands familiar to us today (Voelker & Light 2011). The details have yet to be worked out, but it seems likely that Dartford, Balearic and Marmora’s subsequently evolved on separate islands in the western Mediterranean, and Balearic and Marmora’s have remained isolated there until today.

In most field guides, Dartford Warblers are illustrated with a slate-grey back, but if you glance across at Killian’s plate you’ll notice that dartfordiensis has a brown back. This makes it even easier to separate from male Marmora’s and Balearic Warblers, which like undata have grey backs. Juvenile dartfordiensis are also distinctive when compared with undata.

Killian Mullarney

Killian sketched dartfordiensis on Hartland Moor, where Colin Bibby made his series of classic studies that set him on the path to become the head of conservation science for the RSPB, and later head of BirdLife International’s research team. Killian avidly read Bibby’s papers on Dartford Warbler, having developed a particular interest in the species following his discovery of the third record for Ireland when he was 14 years of age.

Colin Bibby was 20 when he started his study of Dartford Warbler ecology (1977). The work, for which he gained a PhD, looked carefully at the status and habitat needs of the species, translating the results into a plan for its conservation. He showed that Poole Harbour’s Dartford Warblers were dependent on dry, open heathland with mature gorse, and needed the right management to thrive. It was 1968 and there were 31 pairs. Not many, but 50% more than in 1967. It was Bibby who pointed to Stonechats associating with Dartford Warblers. He believed that the Dartfords took advantage of the Stonechats’ vigilance.

Colin Bibby died in 2004, and his obituary in the Daily Telegraph mentioned his reputation for being brusque. “Once, during a study of merlins (small, normally ground-nesting falcons), a team member telephoned to report finding a nest in a tree. Bibby replied: ‘If that’s a merlin’s nest, I’ll eat my hat.’ After seeing for himself that at least one pair had indeed built a nest in a tree, he joined the team for a meal, and a hat was brought to him on a silver salver. He promptly bit off a chunk, chewed and swallowed it.”

Bibby found that Dartfords don’t go far in their lives. He followed this up with a study starting in September 1974, again at Hartland, where he colour-ringed adults and metal-ringed young for two years. He discovered that once paired, the adults will be faithful to the breeding site through snow and fire, and it is the young males that venture further afield. Most often they turn up along the coast in Kent and Sussex, rather than risking a sea crossing. Adults only move a few metres from a favoured gorse bush, and this may explain why their numbers get hammered each bad winter.

Breeding ranges of Atlantic Dartford Warbler (‘Bibby’s Warbler’) Sylvia undata dartfordiensis (red), Mediterranean S u undata (green) and North African S u toni (purple) (after Gabriel Gargallo in Shirihai et al 2001). In shaded areas, it is unclear which of two taxa occurs. It should be stressed that this map is a rough sketch and that, in most coloured areas, the species has a patchy distribution, not being widespread but occurring locally in certain habitats and in numbers that vary from year to year.

So dartfordiensis doesn’t travel far, and has at times been reduced in numbers to a mere handful of birds. This is the classic mechanism for the evolution of an endemic species. Killian jokingly called it ‘Bibby’s Warbler’. Meanwhile I had Greensleeves playing in my head as I thought about the Holy Grail: a real English endemic…. ‘English Warbler’.

However, there is a problem with our new English ‘endemic’. There are quite a lot in France. Distribution maps vary, and it is difficult to know where dartfordiensis stops and undata begins, but Arnoud investigated and it seems that dartfordiensis is the western, maritime race, going right down the Atlantic coast. Curious, Magnus and Killian visited Eugene Archer, a birder friend living in Nantes on the west coast, to find out whether the Dartfords there sounded the same as in Dorset. They found the brown-backed dartfordiensis occupying small patches of habitat much the same as in Dorset (only now they were in the company of Melodious Warblers and Cirl Buntings). Next, Magnus and Killian flew down to Portugal, taking a road trip from Cabo da Roca on the west coast to Monfragüe in central Spain. They found no dartfordiensis, but watched and sound recorded obvious undata in the company of Sardinian Warblers, Spectacled Warblers and Griffon Vultures.

Back home, Magnus was able to analyse sonagrams from a large number recordings of both dartfordiensis and undata. He found some interesting differences. The main call of Dartford Warbler is a low, descending churr, typically a single note, or a two-note call with the second shorter and slightly lower than the first. Much less commonly, three or four-note versions can be heard. The calls vary in pitch, length, number of notes and how frequently they are repeated, depending how excited the bird is.

Dartford Warbler Sylvia undata dartfordiensis, male (at back) and female (pair), Pornic, Loire-Atlantique, France, 28 May 2011 (Killian Mullarney)

Dartford Warbler Sylvia undata undata, juvenile, Monfragüe, Extremadura, Spain, 2 June 2011 (Killian Mullarney)

Dartford Warbler Sylvia undata undata, juvenile, Monfragüe, Extremadura, Spain, 2 June 2011 (Killian Mullarney)

Dartford Warbler Sylvia undata undata, juvenile, Sintra, Portugal, 30 May 2011 (Killian Mullarney)

Dartford Warbler Sylvia undata undata, juvenile, Sintra, Portugal, 30 May 2011 (Killian Mullarney)

Comparing calls of dartfordiensis and undata, Magnus limited himself to males in their second calendar-year or older, to make sure any differences he found were not a matter of sex or age. This left him with 13 recordings of dartfordiensis from Dorset and western France, and 34 of undata calls from Iberia, southern France and Corsica. The result was that male dartfordiensis calls average lower-pitched and slightly longer, with a more gradual descent in pitch and a slightly more ‘grainy’ timbre. Listen to these two examples from the UK (CD1-09) and France (CD1-10), and compare them with calls of undata from Portugal (CD1-11). Male undata calls average slightly higher pitched and shorter, with a steeper descent in pitch and a less grainy timbre. The latter two characteristics give them a somewhat more whining quality. The differences are subtle, and dartfordiensis can sound more like undata when excited.

CD1-09: Dartford Warbler Sylvia undata dartfordiensis Pilot’s Point, Poole Harbour, Dorset, England, 12 May 2002. Calls of a male. Background: Meadow Pipit Anthus pratensis, Eurasian Wren Troglodytes troglodytes, Dunnock Prunella modularis and Common Linnet Linaria cannabina. 02.010.MC.11800.32

CD1-10: Dartford Warbler Sylvia undata dartfordiensis Donges, Loire-Atlantique, France, 11:40, 29 May 2011. Calls of a male. Background: Eurasian Skylark Alauda arvensis and Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica. 110529.MR.114022.01

CD1-11: Dartford Warbler Sylvia undata undata Sintra Cascais Natural Park, Lisboa, Portugal, 10:51, 30 May 2011. Calls of a male. Background: European Stonechat Saxicola rubicola, Sardinian Warbler Sylvia melanocephala. 110530.MR.105134.00

Dartford Warbler Sylvia undata dartfordiensis, juvenile, Donges, Loire-Atlantique, France, 29 May 2011 (Killian Mullarney)

A more basic problem is to tell Dartford Warbler from Common Whitethroat calls. Listen to the whitethroat in CD1-12 and see if you can hear what sets it apart from Dartford. The most helpful difference is the level pitch, not descending as in Dartford, and another important difference is that whitethroat calls are never doubled in the way that Dartford calls often are. Calls of undata are less whitethroat-like, being higher pitched and purer, so less likely to be confused.

CD1-12: Common Whitethroat Sylvia communis Cabo Espichel, Lisboa, Portugal, 08:02, 13 September 2009. Calls of an autumn migrant. Background: wing sound of a Peregrine Falco peregrinus stopping at a pigeon, yellow wagtail Motacilla, Common Nightingale Luscinia megarhynchos and House Sparrow Passer domesticus. 090913.MR.080242.10

We were curious to know whether we could tell calls of males and females apart. When Magnus compared calls of both sexes in three undata pairs, along with a pair of dartfordiensis, it soon became clear that an often-quoted difference in pitch between males and females (V C Lewis in Cramp et al 1992) is unreliable. The only consistent but very subtle difference he found was that males had a clearer voice while the females were more husky or hoarse-sounding. Listen to female dartfordiensis (CD1-13) and undata (CD1-14) and see if you agree.

CD1-13: Dartford Warbler Sylvia undata dartfordiensis Pilot’s Point, Poole Harbour, Dorset, England, 12 May 2002. Calls of a female. Background: Meadow Pipit Anthus pratensis, Dunnock Prunella modularis, Common Blackbird Turdus merula and Common Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs. 02.010.MC.10640.03

CD1-14: Dartford Warbler Sylvia undata undata Monfragüe, Extremadura, Spain, 13:47, 2 June 2011. Calls of a female. The weaker calls in the background are probably a juvenile. 110602.MR.134722.02

Adult Dartford Warblers also have some other important call types besides contact calls. We already mentioned that they vary the number of notes in a call according to how excited they are. Well, when they are really alarmed, eg, by the presence of humans or potential predators near their brood, you start to hear short but rather loud rattles interspersed with the usual calls. Typically, the final note of a normal two-note or three-note call is replaced by a rattle, which can be the length of the replaced note, or up to a second long (CD1-15). Occasionally the first note is omitted altogether, so you just hear a series of short, loud rattles.

CD1-15: Dartford Warbler Sylvia undata undata Rosmaninhal, Beira-Baixa, Portugal, 08:28, 31 May 2011. Rattling alarm calls of a male near nestling or fledglings. Background: Eurasian Hoopoe Upupa epops, Thekla Lark Galerida theklae, song of another male Dartford Warbler, and Corn Bunting Emberiza calandra. 110531.MR.082848.01

Alarm rattles are typically heard at the height of the breeding season, but another, much quieter and generally shorter, twittering trrrt… trrrt... can be heard at any time of year. This can be heard in a variety of contexts, typically from rather excited but not especially alarmed birds, and is often given during short flights. In CD1-16, both members of a pair are giving them. Magnus and Killian also heard these calls from a male repeatedly making short flights, trying to persuade his brood to follow him away from the human intruders.

CD1-16: Dartford Warbler Sylvia undata dartfordiensis Soldier’s Road, Poole Harbour, Dorset, England, 17:00, 5 January 2006. Twittering calls of a pair at dusk, responding to song of a neighbouring male (not heard). Background: European Robin Erithacus rubecula and Common Blackbird Turdus merula. 05.032.MR.11027.12

When following families of Dartford Warblers during the summer, it can be difficult to tell who is who. Some calls of juveniles can be similar to adults. However, when they are begging for food, juveniles use some quiet calls that give away their age. In CD1‑17, listen to the long, low, churring notes, followed by higher-pitched, whining notes. It is the frequent alternation of these two types of sound that readily identifies a juvenile.

CD1-17: Dartford Warbler Sylvia undata dartfordiensis Ham Common, Poole Harbour, Dorset, England, 1 September 2002. Calls of a juvenile begging for food from an adult female, which calls twice at 0:20. Background: European Robin Erithacus rubecula and Common Linnet Linaria cannabina. 02.040.MR.02517.02

The song of Dartford Warbler, both dartfordiensis and undata, is very fast with many notes squeezed into a short song that is surprisingly low-pitched for a bird of Dartford’s small size. Here is a typical example of dartfordiensis, recorded in Poole Harbour (CD1-18).

CD1-18: Dartford Warbler Sylvia undata dartfordiensis, Middlebere, Poole Harbour, Dorset, England, 12 May 2002. Song of a male. Background: Mediterranean Gull Larus melanocephalus, Eurasian Wren Troglodytes troglodytes, Common Blackbird Turdus merula, Common Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs, European Greenfinch Chloris chloris, Common Linnet Linaria cannabina and Yellowhammer Emberiza citrinella. 02.010.MC.04030.02

Stonechat song can sound superficially like Dartford Warbler but is higher-pitched, more whistled, less hurried, and typically sounds a bit slurred. Stonechat also has shorter songs than Dartford. Have a listen to this Stonechat recorded in the dunes along the Dutch coast (CD1-19), followed by another example of Dartford Warbler, this time a dartfordiensis from western France (CD1-20).

CD1-19: European Stonechat Saxicola rubicola, Kennemerduinen, Noord-Holland, Netherlands, 07:46, 20 March 2011. Song of a male. Background: Greylag Goose Anser anser, Great Spotted Woodpecker Dendrocopos major, Dunnock Prunella modularis, Carrion Crow Corvus corone, European Greenfinch Chloris chloris and Common Reed Bunting Emberiza schoeniclus. 110320.AB.074632.02

CD1-20: Dartford Warbler Sylvia undata dartfordiensis Pornic, Loire-Atlantique, France, 11:40, 28 May 2011. Song of a male, recorded from less than 2 m distance. Background: Melodious Warbler Hippolais polyglotta. 110528.MR.110700.11

In southern Europe, other small Sylvia warblers add to the challenge of identifying Dartford Warbler song. For example, the range of undata is almost exactly the part of Dartford’s European range that overlaps with Sardinian Warbler. The two can often be found together, and at times their songs can be difficult to distinguish. Sardinian usually has a drier, more staccato quality, sings slightly less hurriedly and with clearer articulation, and nearly always starts the song with a high-pitched, fairly pure-sounding whistle, which seems to be optional in Dartford. Here is a typical example of Sardinian Warbler song from Portugal (CD1-21).

CD1-21: Sardinian Warbler Sylvia melanocephala Castelo Branco, Beira Baixa, Portugal, 08:29, 13 May 2009. Song of a male. Background: Common Wood Pigeon Columba palumbus, European Turtle Dove Streptopelia turtur, Great Tit Parus major and Cirl Bunting Emberiza cirlus. 090531.MR.082928.01

Undata can sometimes sound rather like Sardinian Warbler, and may even adopt rattles of Sardinian Warbler in its songs. So one way to tell undata songs from dartfordiensis may be to listen for similarities to, or borrowings from, Sardinian Warbler. For example, undata may have a slightly more generous scattering of high-pitched notes and rattles in the song CD1-22 is an example of undata song, recorded at Monfragüe in central Spain, at a location where both species occur in good numbers.

CD1-22: Dartford Warbler Sylvia undata undata Monfragüe, Extremadura, Spain, 11:08, 2 June 2011. Song of a male. Background: Common Swift Apus apus and Spectacled Warbler Sylvia conspicillata. 110602.MR.110832.11

Like several other Sylvia warblers, Dartford has a specialised songflight that it uses in moments of higher excitement. The strophes delivered during these flights tend to be longer than in perched song. Greater length can be achieved by including many repetitions (near or exact) of short fragments. The dartfordiensis in the next recording (CD1-23) gives a songflight 38 seconds into the recording, which lasts for 5.5 seconds. Typical song lengths when perched are in the order of 2-3 seconds, though much shorter songs in flight can also sometimes be heard.

CD1-23: Dartford Warbler Sylvia undata dartfordiensis Glebelands, Poole Harbour, Dorset, England, 09:48, 4 April 2008. Song of a male, with the long final strophe being delivered in flight. Background: Common Pheasant Phasianus colchicus, Eurasian Skylark Alauda arvensis, Eurasian Blackcap Sylvia atricapilla, Common Chiffchaff Phylloscopus collybita and Carrion Crow Corvus corone. 080404.MR.094808.31

Now listen to the undata in CD1-24, which performs a 4 second songflight, with more whistles than its English counterpart.

CD1-24: Dartford Warbler Sylvia undata undata Sintra Cascais Natural Park, Lisboa, Portugal, 12:42, 30 May 2011. Songflight of a male. 110530.MR.124254.21

Dartford Warbler Sylvia undata undata, male, Sintra, Portugal, 30 May 2011 (Killian Mullarney). Recorded on CD1-11 and CD1-24.

Dartford Warbler Sylvia undata undata, male, Sintra, Portugal, 30 May 2011 (Killian Mullarney). Recorded on CD1-11 and CD1-24.

Dartford Warbler Sylvia undata undata, male, Sintra, Portugal, 30 May 2011 (Killian Mullarney). Recorded on CD1-11 and CD1-24.

Dartford Warbler is a species that sings through most of the year, and it is common to hear song in late summer and autumn. At this time, many of the singers are young of the year. In CD1-25, a first-winter in mid-September in Portugal, you can hear a slow transition from a very quiet, hesitant and indistinct subsong to a more confident plastic song. Typically for plastic song, there are many imitations, here including very brief fragments of Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica, Eurasian Wren Troglodytes troglodytes, and two species that can also be heard in the background: Sardinian Warbler and European Greenfinch Chloris chloris. Now listen to another recording of a first-winter in Portugal, made in mid-October (CD1-26). It contains several imitations of Meadow Pipits Anthus pratensis, which arrive in Portugal around the beginning of that month.

CD1-25: Dartford Warbler Sylvia undata undata Cabo Espichel, Lisboa, Portugal, 09:43, 19 September 2008. Song of a first-winter male, slowly changing from hesitant subsong to more confident plastic song. Background: Sardinian Warbler Sylvia melanocephala and European Greenfinch Chloris chloris. 080919.MR.094322.32

Dartford Warbler Sylvia undata dartfordiensis, male, Arne, Poole, Dorset, 9 May 2009 (David Larcombe)

Despite having lost any hope of an English endemic, I still find it an amazing story, these maritime dartfordiensis apparently having stayed close enough to the sea to cling to life despite hard winters and heath fires in the summer. The plumage and sound differences between them and undata certainly merit further investigation. And should dartfordiensis ever be split, it would be nice to think that a future researcher might honour Colin Bibby. It would be a tragedy to call it Nantes Warbler.