Things that go plik in the night (part two)

In part 1 of this article, we explained how to identify Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana flight calls by day and by night, and how we learned these calls. Part 2 looks in more detail at nocturnal autumn migration of Ortolans over two widely separated areas – Dorset, England, and Sintra, Portugal – in a particular year, 2016.

Part 2. Nocturnal migration of Ortolans in Dorset and southern Portugal

We will first put this in context by introducing the three main listening stations where each of the three authors has been recording.

Cabriz, Sintra, and various sites in southern Portugal – Magnus Robb

Magnus Robb took an interest in night migration recording after moving to Portugal at the end of 2008. While enquiring about good sites for diurnal migration, he heard that nocturnal migration could be impressive at Sagres, Vila do Bispo, near Cape St Vincent, the southwestern corner of the European mainland. An old fortress south of the town sits on a peninsula forming the last point of land for birds heading towards Morocco and beyond. At night, it is usually floodlit, which can disorientate migrants and make it more likely that they will call. MR started recording night migration there in early October 2009 and was surprised to record six Ortolan Buntings in the first five hours. Here is the second of those six.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, Sagres, Vila do Bispo, Portugal, 23:12, 3 October 2009 (Magnus Robb). Plik and tew calls of a passing nocturnal migrant. Recorded with Sennheiser MKH-20 microphones in an altered Crown SASS binaural casing.

During the rest of that autumn and the next, MR recorded other nocturnal Ortolan Buntings at Sagres and two other sites. Clearly, the audible migration of this species at night was a normal phenomenon in Portugal. At the end of 2010, he moved house from Lisbon to Cabriz, a village near Sintra, about 25 km northwest of the capital. The following autumn he tried his luck at the house and during one of the first recording sessions an Upland Sandpiper Bartramia longicauda flew over. Despite the neighbours having too many barking dogs, it certainly seemed worthwhile to persevere.

Cabriz is now MR’s main site for nocturnal migration, since no travel is required in order to record there. Due to cars, neighbours, dogs and other noise, sessions usually only start later in the evening when things have become quieter. However, occasional all-night sessions have shown that much fewer birds can be detected during the first half of the night. The same effect does not seem to occur at Sagres, where migration is typically worth recording throughout the night. MR rarely records on spring nights, since the results of a few trial runs have been very disappointing. This is presumably for geographical reasons. Many migrants that passed in the autumn are known to take a more easterly route through Spain when returning to their breeding grounds, and very few long distant land migrants have good reason to pass over the Portuguese west coast in spring.

At Cabriz, Ortolan migration is essentially a September phenomenon, with 79 nocturnal recordings from that month and only 6 from October. So far there are none from August, when MR is often away from home. Elsewhere in Portugal, he has recorded Ortolan twice in August, both times on the last day of the month. In September, Ortolan is among the species recorded most often, after Pied Flycatcher Ficedula hypoleuca and Tree Pipit Anthus trivialis, and the record for one session currently stands at 20 individuals, recorded between 00:20 and 06:41 on 20 September 2012. Occasionally, more than one Ortolan passes at the same time. Here is an example from 26 September 2011 with one near and one distant individual (the more distant one calls for the first time at 0:12).

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, Cabriz, Sintra, Portugal, 03:02, 26 September 2011 (Magnus Robb). Plik, tslew, tsrp and tew calls of two nocturnal migrants, one near and one far (the latter audible from 0:12).

Remarkably, MR has never seen or heard an Ortolan Bunting in the immediate surroundings of Cabriz during the day, although he has seen them migrating along the Atlantic coast just 7 km to the west.

Recording equipment used: Telinga Pro V parabola with stereo DATmic, recording onto Sound Devices 722 solid state recorder.

Old Town Poole – Paul Morton

Spurred on in part by what MR and Nick Hopper (see below) were recording, as well as by the sheer mystery of it all, Paul Morton started recording night migration in February 2015. His first listening station was his back garden in the rural village of Lytchett Matravers, four miles northwest of Poole Harbour, Dorset. During the course of the spring, wader passage was prominent and he also recorded night migrants such as Water Rail Rallus aquaticus, European Nightjar Caprimulgus europaeus and Ring Ouzel Turdus torquatus. Migration petered out in late spring, but waders started moving again in July. By August, passerines featured again, and on 17 August PM noted an unknown call of a bird that had passed at 00:12. He cut it out and filed it away without any real expectation of being able to identify it. A week later at the British Birdwatching Fair, he played the recording to MR who jerked back his head and said, “Where did you say you recorded this?” to which PM replied, “Over my house last week.” MR raised an eyebrow and said, “This sounds like an Ortolan Bunting to me.”

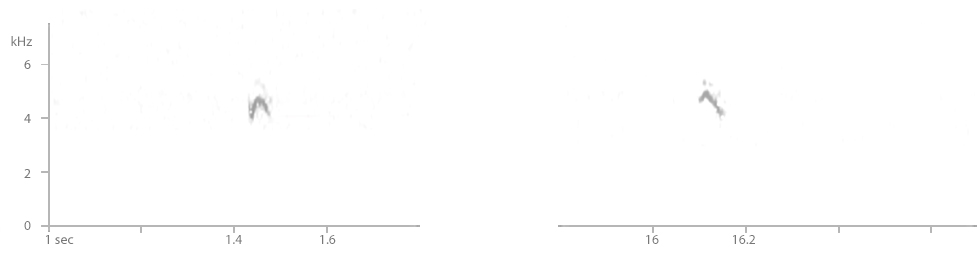

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, Lytchett Matravers, Dorset, England, 00:12, 17 August 2015 (Paul Morton). Single plik call of a nocturnal migrant.

The recording contained a single but entirely typical plik call. As we showed in part 1, plik is the commonest and most easily recognisable of the calls that Ortolan Bunting uses during nocturnal migration. Enthused but nevertheless convinced this would be a one-off, PM continued recording night migration over the following weeks. To his surprise, however, at 04:38 on 10 September he recorded another giving one plik and one tew call.

In 2016, PM decided to move his nocturnal listening station away to a site within Poole Harbour. This was partly to begin a study of night migration within the harbour area for the charity he runs called Birds of Poole Harbour, but also to allow him to place the listening station on a more prominent migration route. He hoped this would result in a wider variety of species and greater numbers of individuals. The new listening station is at the top of a four-story building in the centre of Old Town Poole, an urban environment with virtually no vegetation in the surrounding area to support either resident or migratory birds. Due to the lack of habitat locally, any birds recorded overhead during the night at the appropriate season are very likely to be migrants. Noise from traffic and the local ferry port can sometimes be infuriating, but the expectation of greater variety and numbers proved to be correct. Spring recording was productive with good wader passage and an unexpectedly large Redwing Turdus iliacus movement in March. Autumn recording commenced on 1 August and remained uneventful until 22 August when PM came across a single tew call of an Ortolan Bunting. Much better was to follow the next night when, as the clock struck two, he recorded a long medley of tew and tslew calls of an Ortolan approaching and flying low over the microphones.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, Old Town Poole, Dorset, England, 02:00, 24 August 2016 (Paul Morton). Tew and tslew calls of a nocturnal migrant passing at close range.

The following night, three Ortolan Buntings passed. This late August wave coincided with the first visual records for the autumn at coastal sites such as Portland Bill and Hengistbury Head, as well as other sites on the south coast. Between 25 August and 12 September, PM recorded a further eight Ortolans, bringing his 2016 total to 13 recordings in just 22 days. After this date there was no further sign of them in his night recordings, and visual records by day also tailed off. It will come as no great surprise that PM has never seen or heard an Ortolan near the Old Town Poole listening station during the day.

Recording equipment used: Telinga Pro 8 parabola with stereo DATmic, recording onto a Sound Devices 722 solid state recorder.

Portland Bill and Stoborough – Nick Hopper

Nick Hopper started recording nocturnal migration from the roof of his house in Stoborough, in the far southwestern corner of Poole Harbour, during the autumn of 2012 after being inspired by an email from MR detailing the species he had recently recorded in Portugal. His first thoughts were ‘what a great way to add species to your garden list!’ After persuading The Sound Approach to loan him some equipment, he was ready to go. The parabolic dish went on the roof, and the recorder in the bedroom, connected via some very long cables. All he had to do now was lie in bed with his headphones on and listen. He soon added species such as Common Moorhen Gallinula chloropus, Eurasian Coot Fulica atra and Water Rail Rallus aquaticus to the garden list, and after only three attempts struck gold when a Lapland Longspur Calcarius lapponicus flew over the house. Unfortunately ‘listening live’ proved to be a little anti-social and sessions were rather intermittent until NH adopted the more orthodox approach of leaving the recorder running through the night then checking the sonagrams the next day. The site, adjacent to the Frome Valley, has produced 72 species so far between nautical dusk and nautical dawn (ie, with the sun 12 or more degrees below the horizon). Waders and water birds are a regular feature as might be expected, along with plenty of passerines and oddities such as Mandarin Duck Aix galericulata, Common Scoter Melanitta nigra, Little Grebe Tachybaptus ruficollis, Sandwich Tern Sterna sandvicensis and Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana. In autumn 2014, NH started recording night migration from Portland Bill, Dorset. The volume and variety of migrants passing at Portland proved to be much greater, and NH has subsequently invested more time in this listening station.

The first time NH recorded Ortolan Bunting at night was at Portland Bill on the night of 25-26 August 2016. It was a promising-looking night with heavy cloud cover and occasional pulses of drizzly rain. These conditions together with the date were perfect for a strong audible passage of Tree Pipits Anthus trivialis, and the night’s total came to an incredible 1372 calls (with double and triple calls counted as one). NH spent the first few hours of darkness in the field and to his amazement heard two different Ortolans heading north over the Bill. Later analysis of the night’s recording revealed yet more birds.

Not wanting to push his credibility too far, he selected four examples separated by gaps of 30 minutes or more, and a few days later he uploaded the three best ones to the Portland Bird Observatory website. However, the total number of times that Ortolans passed his microphones that night was 10. Here is one that passed at 22:55. The recording was included in part 1, but it is well worth listening to again. Were these all different individuals? We will come back to this question later. However, since PM recorded three over urban Old Town Poole the night before, there seems no reason to doubt that NH could record an even higher number of them at one of the country’s top sites for Ortolan.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, Portland Bill, Dorset, England, 22:55, 25 August 2016 (Nick Hopper). Several tslew calls of a nocturnal migrant on a night of intense Tree Pipit Anthus trivialis migration.

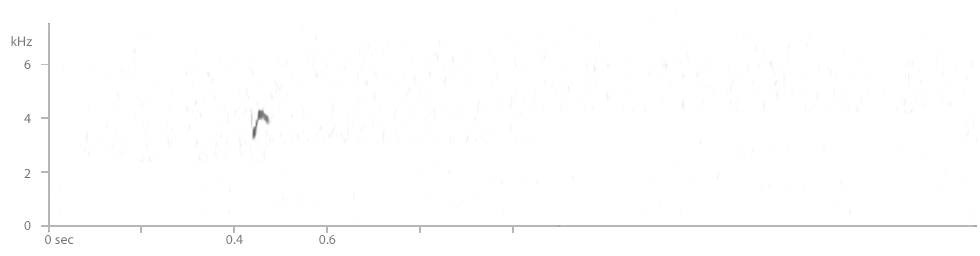

On the night of 30-31 August NH recorded two more Ortolans, this time at Stoborough. Here is one that passed at 01:03, giving a single plik followed by long series of tew calls.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, Stoborough, Dorset, England, 01:03, 31 August 2016 (Nick Hopper). A series of tew calls from a passing nocturnal migrant.

On the night of 2-3 September, another session at Stoborough produced no Ortolans and indeed very little of anything at all. Two nights later at Portland there were none, but the evening of 5 September produced another six Ortolan recordings. At 22:44, one flew over NH who was standing a couple of hundred metres away from his equipment at the time. Here is what was recorded a few moments later.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, Portland Bill, Dorset, England, 22:44, 5 September 2016 (Nick Hopper). Plik and two tslew calls of a nocturnal migrant.

Further sessions at Portland on 18-19 and 19-20 September, and at Stoborough on 23-24 September produced no further recordings. However, the odd Ortolan was still being seen during the daytime hours on Portland until 19 September. Portland has always been one of the best places in England to see Ortolan Bunting, and 2016 was a good year.

Equipment used: Telinga Pro 8 parabola with stereo DATmic, recording onto Tascam HD-P2 solid state recorder.

How we analyse the recordings

Anyone first hearing about our habit of making all-night sound recordings is bound to ask, when do we ever find the time to listen to them? The answer is that we don’t. We import the recordings into a software program that produces a sonagram: a visual image of the recording. We scroll through these quickly in search of tell tale shapes of flight calls, which we then listen to. We log species and numbers, archiving the more interesting recordings for future reference.

The software we use is Raven Pro, currently in version 1.5 (birds.cornell.edu/brp/raven/). The time it takes to go through the recording depends on how much migration has taken place through the night. A quiet night might take less than an hour, but a night with many challenging calls to be identified, counted and filed away can take many hours. It is often only some days later that we appreciate fully what went on during a given night, and this is why news sometimes gets out slowly.

Results

Ortolan Bunting nocturnal flight call recordings in 2016

Table 1. Medleys of Ortolan Bunting nocturnal flight calls, recorded by the authors during the autumn migration period in 2016. The abbreviations given under Loc (location) are as follows: OTP – Old Town Poole, Dorset, England; SB – Stoborough, Dorset, England; PB – Portland Bill, Dorset, England; OD – Odeceixe, Aljezur, Portugal; CZ – Cabriz, Sintra, Portugal.

| Loc | Date | Time | Medley of calls recorded |

|---|---|---|---|

| England | |||

| OTP | 22-aug | 22:47 | tsrp |

| OTP | 24-aug | 02:00 | tslew, tew, tew, tslew, tslew, tew, tslew, tslew, tslew |

| OTP | 24-aug | 22:40 | plik |

| OTP | 25-aug | 01:31 | plik, tew, tew, tsrp, tew, tew, tsrp, tslew |

| OTP | 25-aug | 03:08 | tew, tew, tew, tew |

| OTP | 25-aug | 22:27 | tew |

| OTP | 27-aug | 02:03 | plik |

| OTP | 29-aug | 21:37 | plik, tslew |

| OTP | 30-aug | 03:34 | tsrp, plik |

| OTP | 01-sep | 02:33 | plik, tew |

| OTP | 05-sep | 20:53 | tsrp, tslew, tslew, tslew |

| OTP | 07-sep | 02:46 | tsrp, tslew |

| OTP | 12-sep | 01:12 | plik |

| ST | 31-aug | 01:03 | tew, tew, tew, tew, tew, tew |

| ST | 31-aug | 02:11 | plik, tew |

| PB | 25-aug | 21:33 | tew, tew |

| PB | 25-aug | 21:55 | tsrp |

| PB | 25-aug | 22:35 | tsrp, tsrp |

| PB | 25-aug | 22:55 | tslew, tslew, tslew, tslew, tslew, tew, tslew, tew |

| PB | 25-aug | 23:25 | tew, tew, tew |

| PB | 25-aug | 23:27 | plik, tew, plik |

| PB | 25-aug | 23:29 | tew, tew, tew, tew |

| PB | 26-aug | 00:12 | plik |

| PB | 26-aug | 00:35 | plik, plik, plik, plik (possibly two individuals) |

| PB | 26-aug | 02:06 | tslew, tslew |

| PB | 05-sep | 21:17 | plik, tew |

| PB | 05-sep | 21:39 | plik |

| PB | 05-sep | 21:54 | tslew, tsrp, tsrp, tsrp |

| PB | 05-sep | 22:35 | tsrp, plik |

| PB | 05-sep | 22:40 | plik |

| PB | 05-sep | 22:44 | plik, tsrp, tsrp |

| Portugal | |||

| OD | 31-aug | 01:31 | tew, tup |

| CZ | 02-sep | 01:21 | plik |

| CZ | 03-sep | 03:26 | plik, puw, tslew, puw, tslew |

| CZ | 03-sep | 05:21 | plik, tsrp? |

| CZ | 03-sep | 05:32 | plik, plik |

| CZ | 17-sep | 00:06 | tew, tsrp, tew |

| CZ | 17-sep | 00:13 | plik, tslew? |

| CZ | 17-sep | 01:29 | tsrp |

| CZ | 17-sep | 01:46 | plik, plik, plik |

| CZ | 17-sep | 01:49 | tew, tew |

| CZ | 17-sep | 02:54 | plik, tsrp |

| CZ | 17-sep | 03:07 | plik, plik |

| CZ | 17-sep | 03:57 | plik, tew |

| CZ | 17-sep | 05:12 | plik |

| CZ | 18-sep | 23:18 | unclear, plik |

| CZ | 18-sep | 23:54 | plik |

| CZ | 19-sep | 00:44 | tew, tsrp, plik, tslew, plik, vin (two individuals) |

| CZ | 19-sep | 00:51 | tslew |

| CZ | 19-sep | 01:48 | tslew, tsrp? |

| CZ | 19-sep | 02:19 | plik, tup, tup, tup |

| CZ | 19-sep | 02:38 | plik |

| CZ | 19-sep | 22:50 | tew, tew |

| CZ | 06-okt | 06:24 | plik |

Do all the recordings in Dorset represent different individuals?

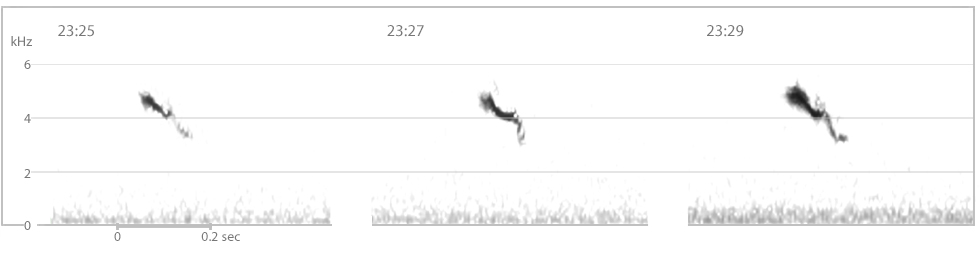

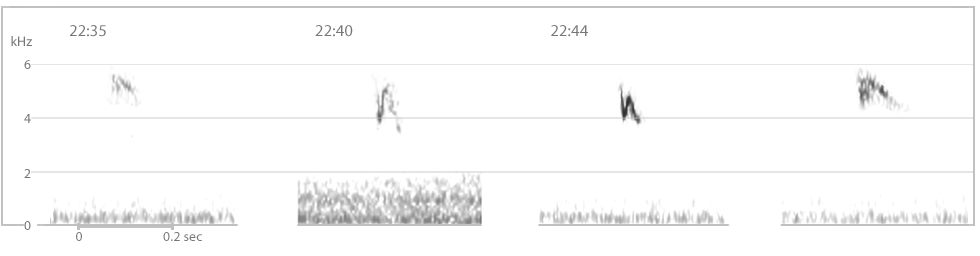

In late August 2016, when the news first emerged that we had sound recorded multiple Ortolan Buntings flying at night over Dorset, sceptics wondered whether this was all down to one or two birds flying circuits, and being responsible for multiple detections. At Old Town Poole this seems extremely unlikely because of the habitat – an urban centre – and besides, all recordings were separated by at least 97 minutes. At Portland Bill, however, there were a couple of obvious clusters of records: three detections in under five minutes on 25 August (23:25-23:29) and three detections in under 10 minutes on 5 September (22:35-22:44).

Several interpretations are possible. Perhaps in both cases a group of three took off from a feeding area at dusk, gradually became separated in the dark, and each individual ended up passing the Bill at a slightly different time. Alternatively, a single bird could have flown a couple of circuits of Portland Bill before deciding how to procede further. On 25 August, there was heavy cloud cover with occasional drizzle and the fog horn was in operation, conditions that could cause some disorientation. On 5 September, the sky was overcast but it was not raining.

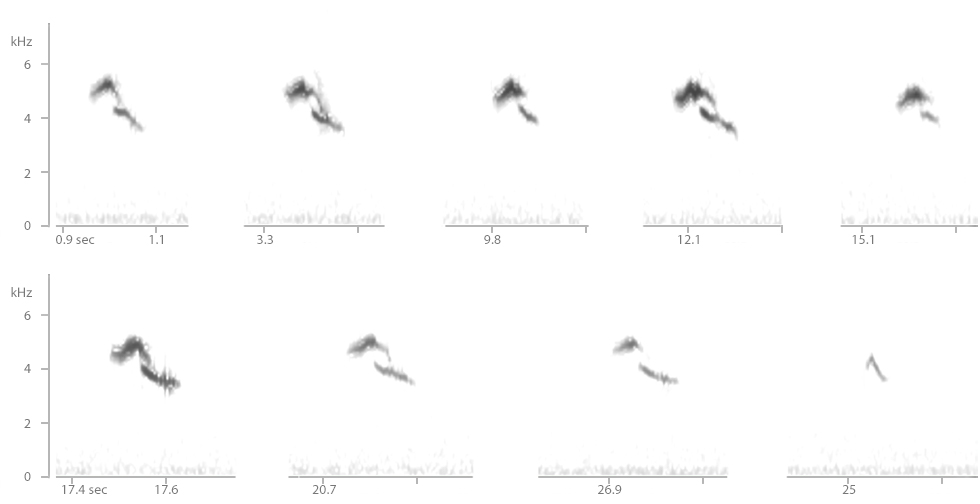

During such conditions it was also possible that birds could have been temporarily grounded for short periods of time during heavier bouts of rain. One way to shed some light on the problem is to consider the actual calls recorded. After viewing sonagrams of over 140 recordings of nocturnally migrating Ortolans, it seems clear to us that calls of a given type from the same individual are usually more similar than calls of the same type from two different individuals.

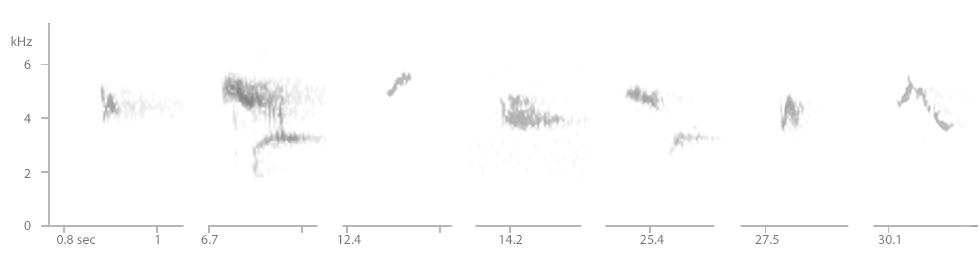

For this reason we compared each recording from Portland Bill with the two before and after on the same night. It was striking that the tew calls at 23:25, 23:27 and 23:29 on 25 August all had a very similar shape, even if the one at 23:27 was angled differently in its final, lowest part. It seems likely that the same individual was involved in all three.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, Portland Bill, Dorset, England, 23:25, 23:27 & 23:29, 25 August 2016 (Nick Hopper). Tew calls from three recordings made with gaps of two minutes between them. Probably the same individual was in all three.

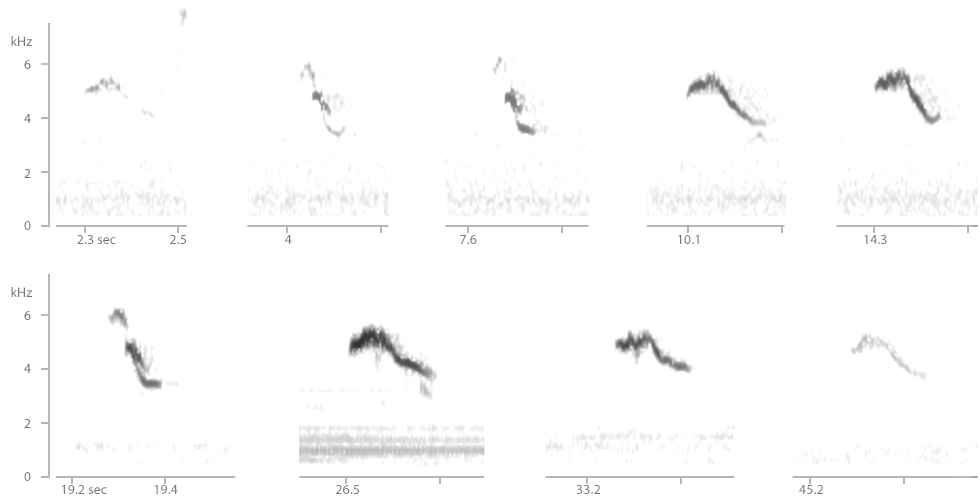

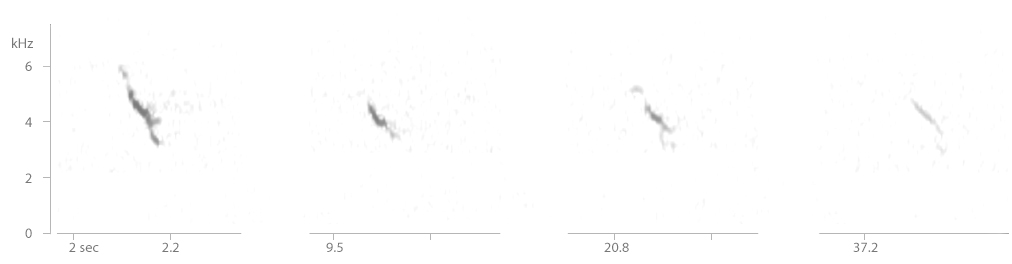

In the sequence of three detections in under 10 minutes on 5 September, the tsrp calls at 22:35 and 22:44 are very similar in pitch, timbre and shape, and the plik calls at 22:40 and 22:44 are similar in frequency range if not exactly in shape. Perhaps here also, the same individual was involved in all three.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, Portland Bill, Dorset, England, 22:35, 22:40 & 22:44, 5 September 2016 (Nick Hopper). Tsrp and plik calls from three recordings all made within 10 minutes and probably involving the same individual.

Based on the above we will err on the side of caution and propose 27 individuals from the 31 recordings of Ortolan Buntings detected nocturnally in Dorset in 2016.

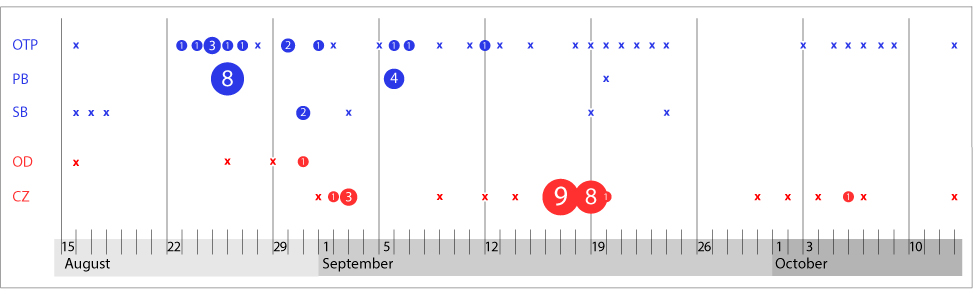

Phenology of nocturnal Ortolan Bunting migration at five listening stations. Numbers refer to estimated number of individuals, which may differ from the number of recordings. Nights when we recorded migration but detected no Ortolans are indicated with a cross mark. Dorset locations blue; Portuguese locations red.

Variable amounts of information in nocturnal recordings

In part 1, we showed how to identify eight different call types of Ortolan Bunting, seven of which we have also detected at night. As we showed, nocturnal and diurnal versions of these calls do not differ. Some, such as plik are highly distinctive, while others such as tsrp are more likely to invite confusion with other species.

Recordings of nocturnally migrating Ortolan Buntings can contain vastly different amounts of information. The main variables concern the number, variety and clarity of calls. It is undeniable that a recording with five different known Ortolan call-types, some of them repeated, and passing at close range can be more securely identified than one containing a single distant tsrp call.

With sound identification, just as with visual identification, the more features that point in the same direction, the better. In this respect Ortolan Bunting, with so many different call types, offers greater chances of secure identification than a species with few and rather undistinctive call types ever could. In 2016 the mean number of call types given by a passing nocturnal Ortolan was 1.56 (range: 1 – 5); 58% only gave a single call-type while within range of the microphones. Of the latter group, 16 used plik, 8 tew, 4 tsrp and 2 tslew.

What weather conditions are best for detecting Ortolans at night?

Stars are among the most important means by which birds navigate at night (Newton 2008), and on a clear night in autumn many birds will be migrating. When conditions are favourable for them many of these birds, particularly passerines, will be at a high altitude and therefore beyond the range of our listening equipment. We have found that nights with heavy cloud cover and even intermittent light rain often give the best results, presumably because birds are forced down to a more audible altitude.

During 2016, the best nights in Dorset were mild with dense cloud cover. Prior to 2016, NH chose to record only on nights with no or little cloud cover, since he was concerned that the expensive recording equipment might not be waterproof. During those times, although he recorded many species, passerine numbers were much lower than in 2016 and he detected no Ortolan Buntings.

The two best nights in Portugal in 2016 coincided with high pressure over the Iberian peninsula. MR associates good Ortolan nights with light tailwinds and cloudy conditions, although multiple individuals may also pass on clear nights. Northerly tailwinds are the norm in Portugal in late summer/early autumn. Indeed, it may be for this reason that so many Ortolans head so far west in autumn, to hitch a ride to subsaharan Africa on the prevailing northerly winds of the Iberian west coast.

Was 2016 an exceptional year in Dorset?

It is impossible to say whether, in terms of nocturnal migration, 2016 was an exceptional year for Ortolan Buntings in Dorset. We simply do not have comparable coverage from other years. In terms of visual sightings, however, it was a good year. The Portland Bird Observatory blog lists a minimum of 12 flighty individuals seen between 26 August and 19 September 2016. None were “pinned down and showing”, and only the very last one lingered long enough to be photographed. However, there was no obvious link between numbers seen during the day and numbers recorded during the night.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, Portland Bill, Dorset, England, 19 September 2016 (Martin Cade).

Why so many Ortolans at night?

Why is a species that is scarce or even rare during the day among the ones that we pick up most frequently at night, even in places where we have never seen or heard it during the day? It is not the only such species. Tree Pipit Anthus trivialis is another that manages to keep a very low profile during the day, even for observers very familiar with its calls. During the night, however, we sometimes detect heavy passage (eg, the 1372 calls at Portland Bill on 25-26 August 2016 referred to above). In North America, Catharus thrushes are notoriously difficult to detect as migrants during the day and yet, as nocturnal migrants they are available to anyone who makes the effort to listen for them, often passing locations where they have never been detected in any other way (Evans & O’Brien 2002). Is Ortolan simply a shy species like Tree Pipit and the Catharus thrushes, but highly vocal as a nocturnal migrant? Perhaps it really is that simple.

After learning to recognise calls of Ortolan Bunting, our experience has been that most autumn observations by day concern birds flying past or, much less often, flushed. Occasionally a bird flushed unexpectedly will perch on a nearby bush, allowing us perhaps brief views. However, opportunities for identifying them only by visual means are very limited. Even in Portugal where Ortolan is not particularly rare, you need enormous luck to chance upon a feeding site. If you do find one during the peak of migration, it may hold several 10s of individuals. MR knows of just two such sites in southern Portugal. Probably there are many more, in arable land not often frequented by birders.

There are many species we know to be much commoner night migrants than Ortolan Bunting, which we never or only very rarely detect during our listening sessions. An obvious group to mention here is the old world warblers, of which only Phylloscopus seem to give the occasional call in nocturnal flight (10 in eight years of recording: MR). Also, many but not all of the chats, such as Whinchat Saxicola rubetra and Common Redstart Phoenicurus phoenicurus, appear to migrate silently. Among buntings, Common Reed Bunting E schoeniclus is mysteriously rare in our nocturnal recordings, despite being a common migrant and calling frequently while migrating during the day. At night, Ortolans seem to feature disproportionately often in our recordings, compared to many other species. Why should this be?

One possibility is that Ortolan Bunting flies lower than other nocturnal migrants, increasing our chances of detecting it. Why might it do this? Migrants are thought to choose the height they migrate at based on the help they receive from wind strength and direction (Bruderer 1971, Richardson 1976). So there would have to be some major advantage to flying low, in order to compensate for the advantages of choosing a more aerodynamic stratum, usually higher in the sky.

Conclusion

We confess that we are still almost as amazed by the number of Ortolans we are detecting at night as we were when we first started detecting them. Who will join us in trying to shed more light on the phenomenon? Lets find out where else besides Dorset and southern Portugal they can be detected migrating at night, and where the numbers are highest. And having established that numbers migrating through England are higher than previously thought, lets try to work out where they are hiding during the day.

Meanwhile, what other surprises await discovery? Who will be the first to detect a Catharus thrush or an Olive-backed Pipit A hodgsoni migrating over a western European location at night? Or one of the eastern relatives of Ortolan Bunting: a Cretzschmar’s Bunting E caesia or even a Grey-necked Bunting E buchanani? Many exciting rewards are possible in this ‘new’ branch of birding, and they are open to anybody curious enough to give it a try.

References

Bruderer, B 1971. Radiobeobachtungen über den Frühlingszug im Schweizerischen Mittelland. Ornithologischer Beobachter 68: 89-158.

Evans, W R & O’Brien, M 2002. Flight calls of migratory birds. Eastern North American landbirds. CD-ROM. Old Bird Inc.

Newton, I 2008. The migration ecology of birds. London.

Richardson, W J 1976. Southeastward shorebird migration over Nova Scotia and New Brunswick in autumn: a radar study. Canadian Journal of Zoology 57: 107-124.