4 – The Fourth

What to do when your two trips up river teaching folk about bird songs are cancelled due to circumstances. Write about last year.

Cetti’s Warbler Cettia cetti Texel, Noord-Holland, Netherlands, 8 April 2020 (Jos van den Berg).

At the end of April 2019, I was guiding on a beautiful boat trip organized by Paul Morton to teach bird song. As we gently pushed up the River Frome I was pointing out songs of the various Cetti’s Warblers Cettia cetti that live along the riverbank when a woman asked me if I knew that the 4thmovement of Beethoven’s 2ndsymphony was based on the song of Cetti’s Warbler? Well, yes, Bryan Bland had mentioned something on a previous trip. This brings me into dangerous territory. You know, the same territory where birdy talk and other handy mnemonics live.

I am listening to the 4thmovement as I type and yes, the repeated four notes do sound a bit like it, but surely not if you listen carefully. Beethoven wrote it in Heiligenstadt, an Austrian spa resort where he had gone for his health in 1802. Although it is reasonable to think that he could still hear Cetti’s Warbler, despite his worsening deafness, they weren’t there then (or now). He may have remembered them from elsewhere. Meanwhile, in what is described in Wikipedia as “an example of musicologist overreach”, Robert Greenberg of the San Francisco Conservatory of Music describes the highly unusual opening motif as a hiccup, belch or flatulence followed by a groan of pain”. According to him the motifs are supposed to be inspired by, and represent, Beethoven’s stress-driven digestive issues and flatulence, and give a whole new meaning to ‘the expression’ of the 4thmovement.

Well at least I thought it was Beethoven’s second symphony fourth movement until, just now, Bryan phoned me up to talk about upcoming boat trips, and by the by he told me that it’s the 2ndmovement of Beethoven’s 4thpiano concerto. This not only ruins a beautiful story, but proves my point even more.

Back on the boat, I explained that each ferocious and explosive song of a male Cetti’s Warbler is a little different to the next male’s song, and it stays constant throughout his life. In one study of 250 different males, only two had identical songs. Although superficially close enough to each other for us to recognize them immediately as Cetti’s, not only are each of these songs specific to the individual, but each male and female in the typically polygamous group will recognise a stranger if it sings in the group’s territory.

Cruising up the river, we listen carefully together to each male as it demonstrates my point,and my classically educated guest says she canhear the differences.

Meanwhile I feel that rather than having been illuminated through science I have behaved like Captain Hook from Barrie’s Peter Pan, and that somewhere along the riverbank a fairy has died. What do I mean by that… I have to admit if you want to walk the plank tell me that a Common Blackbird Turdus merula song always reminds you of your grandfather whistling, then add joyfully that the song of European Robin Erithacus rubecula sounds like a little boy also imitating him walking behind him heading to the allotment. I can’t bear the imprecision.

Cetti’s Warbler Cettia cetti in fresh first-winter plumage, Lesvos, Greece, 19 August 2013 (Killian Mullarney).

Cetti’s Warbler Cettia cetti in fresh first-winter plumage, Lesvos, Greece, 19 August 2013 (Killian Mullarney).

It’s not as if authors haven’t been trying to inject a little precision into descriptions of bird song for some time; the authors of Witherby’s Sound Guide (North & Simms 1958) first suggested that you can represent: “… comparative pitch… by what is known as the ‘vowel scale’, where ee, for instance, indicates a note of high pitch, ah of mediumpitch and oo of low pitch. If the syllables are whispered it will be found that the vowels do in fact sound according to this scale, and a whisper is itself of high pitch and thus likely to approximate to the pitch of a bird-call better than the human voice. … These usually sound silly, but are so useful that the silliness is worth putting up with”.

I think my problems with this all come back to one thing. If I suggest that Cetti’s Warbler song goes twack twack… diddlediddle… twack twack, apart from sounding silly this implies that the species sings only one song. As I have explained, however, if you listen carefully it doesn’t.

It was during a holiday with my family in Cyprus that I first started really listening to bird sounds. It was Easter 1994, and I had never recorded a bird sound before. I have a good friend, Jeff Osment. Just to show how good, he wrote a book about our friendship (The Road to Pelindaba, 2018). Jeff is a filmmaker and he had sound recording gear, which I borrowed to see how I got on with bird sound recording

I took a villa with my family in the hills above the Baths of Aphrodite on the island of Cyprus. Not knowing much about my own family history, I always had a romantic notion that with a name like Constantine I probably had Greek-speaking forbears, possibly from Cyprus. Jeff’s book based on the exploration of my family tree sorted that out; my forebears come from Bolton but hey, he hadn’t written the book back then.

At the back of the villa was a deep, dry riverbed in a stony gulley. During the day it was a great place to hear migrants fly over – Greater Short-toed Larks Calandrella brachydactyla, Tawny Pipits Anthus campestris, yellow wagtails Motacilla sp and Ortolan Buntings Emberiza hortulana – while Great Tits Parus major and European Goldfinches Carduelis carduelis were singing in the pines scattered along the gulley. Intrigued by the differences between calls of Thrush Nightingale Luscinia luscinia and Common Nightingale L megarhynchos, and curious to hear how Cyprus Scops Owl Otus cyprius and Eurasian Scops Owl O scops differed, I would sit out after dark listening and now recording.

Using Jeff’s tape recorder and gun microphone, suddenly I could hear the strange gulping sound Common Quails Coturnix coturnix make before their wet-my-lips, then there was all that amazing detail in Eurasian Stone-curlew Burhinus oedicnemus calls and wow, that noise like a coffee machines steamer must be one of the calls of Common Barn Owl Tyto alba. I got very excited on hearing a deep series of hoots roughly one every three seconds. For three nights I was up recording what I assumed was a Long-eared Owl Asio otus in the pines.

After a few nights of hooting I searched for physical signs of the owls, walking the gulley right down to the sea. I stopped to watch Common Ostriches Struthio camelus displaying at a local ostrich farm. Their displays were silent and extremely flouncy, but I started to wonder if they got noisier after dark. That night I revisited, and sure enough their visual displays had been replaced with repetitive deep hoots.

Having solved my first sound mystery, I moved on to another. An hour or so before dawn there was this song, a sort of fast Chip chip didy chip given repeatedly around six or seven times a minute, with a call note here and there. After several mornings I traced it to a Cetti’s Warbler, but why wasn’t it singing ‘normally’. That mystery took 25 years to solve.

Magnus asked me the other day if I have been listening differently since my weeks with the Don. No not really, that happened way before I met him. In the last article I mentioned Don Kroodsma’s book The Singing Life of Birds (2005). What I didn’t say was that I have imagined being invited onto BBC Radio 4’s Desert Island Discs and having got through my ten favourite bird songs, choosing this as my only book. If I could only take a few pages, it would be where he describes listening as pre-dawn songs of Chestnut-sided Warblers Setophaga pensylvanica sweep over the forested hills of Berkshire, Massachusetts.

In it, Don listens to song after song, comparing as the birds sing pre-dawn from their densely packed territories. Typically, he marks the sequence in which new song phrases appear or return using A, B, C and so on, thereby working out how songs are structured and varied, and how each individual Chestnut-sided Warbler’s song differs from its neighbour’s. While this is true before dawn, half an hour later they all converge on any of just four variations of the more stereotypical pleased.. pleased.. pleased.. to meetcha.

So Chestnut-sided Warblers sing pre-dawn songs just like my Cetti’s Warblers on Cyprus. But why haven’t I heard Cetti’s pre-dawn song in Poole or Weymouth where they abound?

I was brought up in Weymouth. Not so interested in birds then, I preferred pond life. The best place for pond dipping, especially for the rare, nasty and much sought-after Water Scorpion Nepa cinerea, was Chafeys Lake, a marshy area at the top end of the Radipole RSPB reserve. While Cetti’s Warbler was arriving from France and colonising Chafeys Lake so Mo, Jeff and I moved from Weymouth to London, and by 1978 when we moved back, there were 12 singing males.

Cetti’s Warbler Cettia cetti Lesvos, Greece, 14 April 2015 (Ian Lewington).

Doug Ireland took over as warden of the reserve in the seventies, and he started to study the new arrival with a team of volunteers. Magnus and I met a couple of them decades later, and they told us of nights spent in the field proving that Cetti’s sing during the night. They observed that a fair proportion of the Cetti’s there were polygamous with up to three or four females to each male. The complexity of the relationships was described in glorious detail (Bibby 1982).

Birds don’t listen quite as we do. They perceive pitch well, but loudness less well. We humans can determine a difference in the intensity of a sound of around 1 dB, whereas a bird typically requires a difference of 2-4 dB before it notices (Dooling 2004). It’s an intriguing thought that a Cetti’s Warbler may not even realise that it’s shouting.

As time passed, Killian recorded Cetti’s Warblers in Lesbos singing the predawn song. However we couldn’t find examples in the great marshes of Mallorca. We started to wonder if it might be a feature of the eastern sub-species orientalis or even a hint of speciation. Magnus recorded a marvelous sequence in Mallorca where the two males went through their entire vocabulary, fanning their wings at each other, but still we didn’t get to the bottom of the puzzle.

1) Cetti’s Warbler Cettia cetti Parc Natural S’Albufera, Mallorca, Spain, 5 April 2003 (Magnus Robb). Intense conflict between two males. Background: White-throated Wagtail Motacilla cinereocapilla. 03.008.MR.12746.00

Then Don agreed to visit us in Mallorca and Holland to explore old world warbler songs. I have spent a lot of time in North America and I realised that our warbler songs are much more complex that theirs, so to break him in, and perhaps to see if we could solve the riddle of predawn singing, I suggested we started with Cetti’s.

Each morning before dawn Don, Janet, Mo and I went to the northern corner of Albufera where Cetti’s Warblers abound, and waited until they started singing after 07:00.

Don liked his territories to be lined up. He recorded birds on either side of a bridge but gave up. We found a line further along which he recorded. Afterwards we sat in the villa where he analysed his recordings while I went through BWP’s (Cramp 1992) vocal section for Cetti’s Warbler with a highlighter pen. We worked hard but even with Don as a talisman we didn’t achieve enlightenment.

Magnus solved it for me in the end when he recorded pre-dawn singing at 01:20 and 02:31 on 10 March along the River Guadiana in Portugal. Then I recorded it from the River Piddle in Dorset, and he made another recording of it from a small river in the north of Mallorca.

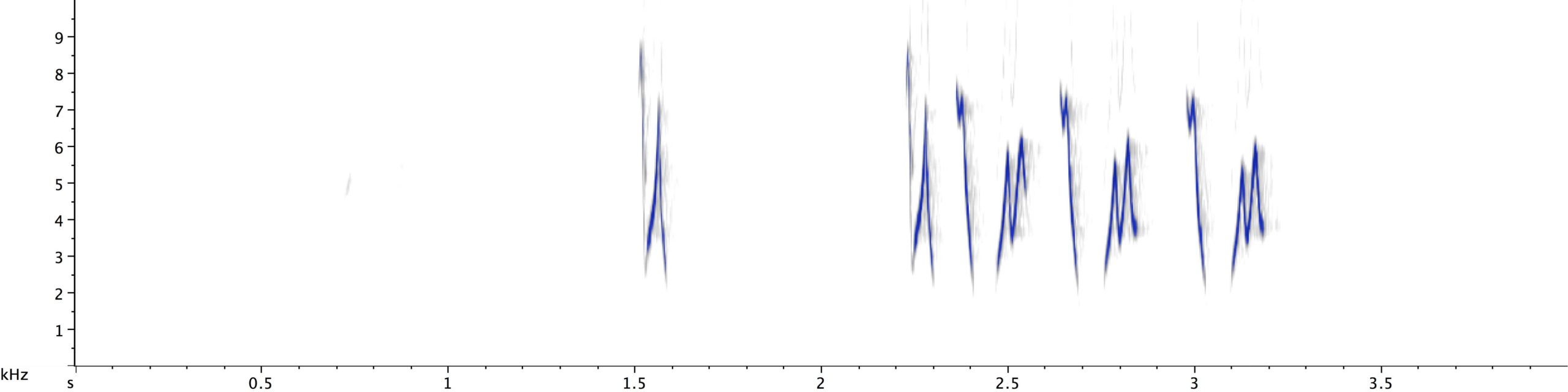

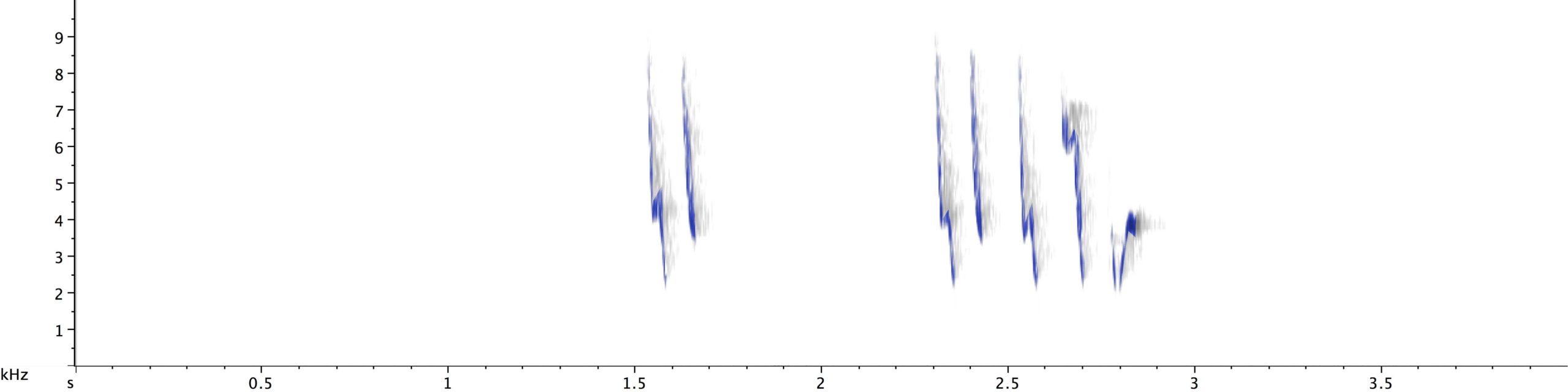

Listening more closely to Cetti’s Warbler pre-dawn song, it starts with an emphatic sound then a gap followed by four or five more emphatic sounds. Reading that description you could think I was describing normal song, but pre-dawn song is much softer and repeated far more frequently. This, and the fact that the recordings in the digital version do not correspond with the sonagrams in the book, no doubt led us to misunderstand BWP, which describes it rather obliquely as a mate attraction song.

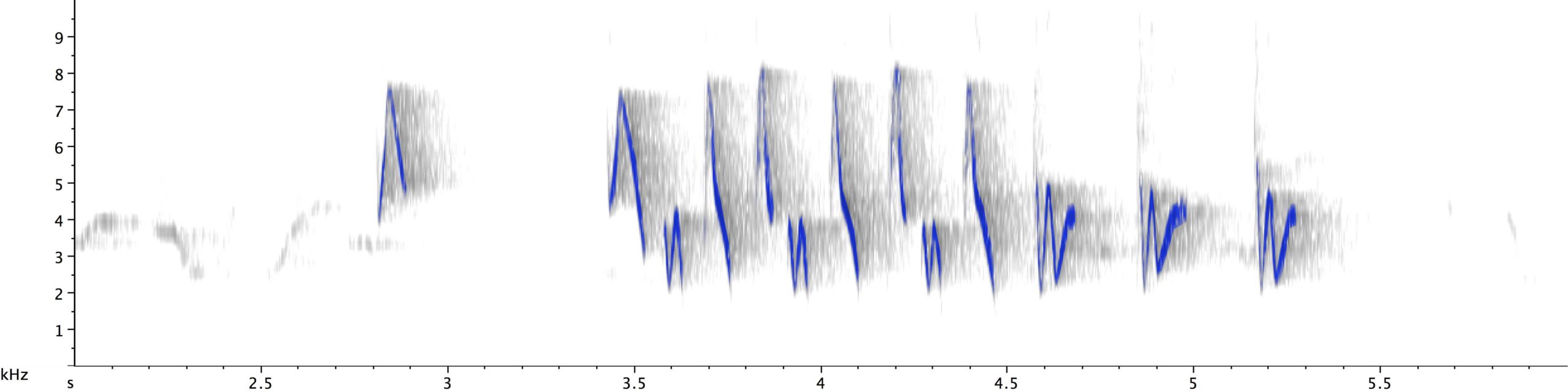

Let us put you out of your misery. Here are recordings of four different Cetti’s Warbler songs with the usual long gaps (2 – 5), and two examples of predawn song (6 & 7).

2) Cetti’s Warbler Cettia cetti Port de Pollença, Mallorca, Spain, 08:57, 10 May 2016 (Magnus Robb). Territorial song of a male, answering a neighbour some distance away. Background: Eurasian Blackcap Sylvia atricapilla, Mediterrean Flycatcher Muscicapa tyrrhenica, European Goldfinch Carduelis carduelis and European Serin Serinus serious. 160510.MR.085728.01

3) Cetti’s Warbler Cettia cetti Middlebere, Dorset, England, 09:48, 29 April 2011 (Mark Constantine). Territorial song once. Background: Canada Goose Branta canadensis, Common Cuckoo Cuculus canorus and Common Chiiffchaff Phylloscopus collybita and Eurasian Reed Warbler Acrocephalus scirpaceus. 110429.MC.094801.01

4) Cetti’s Warbler Cettia cetti Parc Natural S’Albufera, Mallorca, Spain, 06:38, 24 March 2014 (Mark Constantine). Territorial song of several different individuals. Background: Common Moorhen Gallinula chloropus, Eurasian Coot Fulica atra, Little Ringed Plover Charadrius dubius and European Serin Serinus serinus. 140324.MC.063800.02

5) Cetti’s Warbler Cettia cetti Donges, Loire Atlantique, France, 09:35, 29 May 2011 (Magnus Robb). Territorial song. Background: Melodious Warbler Hippolais polyglotta. 110529.MR.093513.01

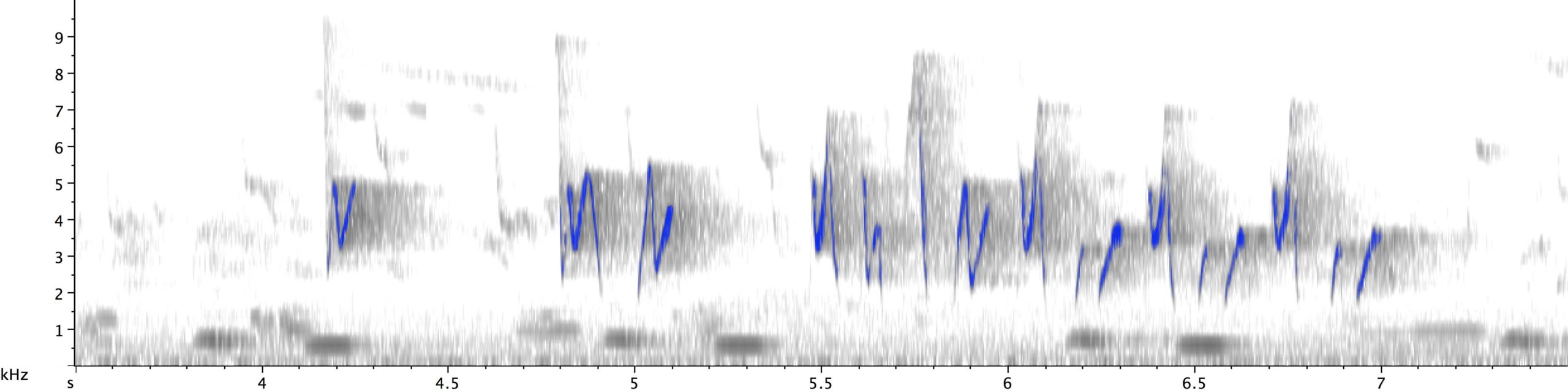

6) Cetti’s Warbler Cettia cetti Asprokremnos dam, Paphos, Cyprus, 06:00, 7 April 2000 (Magnus Robb). Pre-dawn song. Background: Chukar Alectoris chukar, Little Grebe Tachybaptus ruficollis, Eurasian Coot Fulica atra and Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica. 00.013.MR.04929.01T

7) Cetti’s Warbler Cettia cetti Skala Kallonis, Lesvos, Greece, 02:30, 27 April 2001 (Killian Mullarney). Pre-dawn song. Background: Water Rail Rallus aquaticus. 01.008.KM.02421.11T

In the end we agreed with BWP and assume it is unattached males that produce pre-dawn song. Cetti’s Warblers in Britain can’t really sustain living along a river all year and have to retreat to reed beds to winter. We assume that in reed beds territories are soon filled, and males can even afford multiple females, whereas at the edges of linear territories males may actually need to put in some effort to attract a mate. Even if that conclusion is wrong we do know that pre-dawn song is not exclusive to Cyprus and so not as important as we first thought.

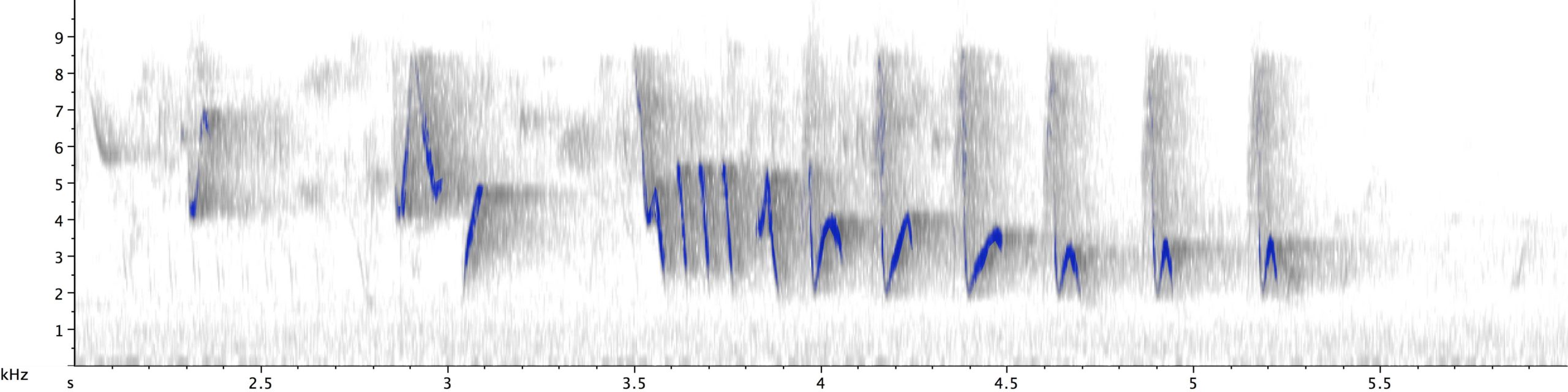

Before I go, I’ve asked Magnus to choose examples of some of the other sounds of Cetti’s Warbler for you to hear. It’s amazing how many of them were in the recordings he made of that conflict sequence on Mallorca in 2003. One of those was recording 1 above. Here is another recording from the same situation.

8) Cetti’s Warbler Cettia cetti Parc Natural S’Albufera, Mallorca, Spain, 5 April 2003 (Magnus Robb). Song duel of two males, with soft hui calls presumably given by an unseen female. Background: Eurasian Coot Fulica atra and Zitting Cisticola Cisticola juncidis. 03.008.MR.12312.00T

These two males really pulled out all the stops. For a start, we can hear both of the song types I have already mentioned: loud strophes normally delivered at a rate of about two per minute, and a shorter more chattering strophes delivered with much shorter gaps, quite often before dawn in the morning. The first strophes in the above recording (8) are of this second type. At 0:23, there is a rattling sound, similar to a call that can often be heard separately. Here is an example of a pair of Cetti’s Warblers in the Netherlands (9), where the rattle was almost certainly being given by a female, followed by a song from the male. Then another example where a rattle is delivered in isolation (10).

9) Cetti’s Warbler Cettia cetti Napoleonhoeve, Zeeland, Netherlands, 15 April 2006 (Magnus Robb). Rattle of a female, followed by song of a male. Background: Common Shelduck Tadorna tadorna and Common Chiffchaff Phylloscopus collybita. 06.007.MR.04715.01

10) Cetti’s Warbler Cettia cetti Napoleonhoeve, Leziria Grande, Vila Franca de Xira, Portugal, 18:26, 14 April 2019 (Magnus Robb). A single loud rattle. Background: House Sparrow Passer domesticus. 190414.MR.182615.01

According to Cramp (1992), both sexes make this rattle, but females perhaps more often. Cramp also mentions another call type that is commonly given by females in the presence of males, a soft hui. You could also hear it in recording 8, and here it is on its own.

11) Cetti’s Warbler Cettia cetti Parc Natural S’Albufera, Mallorca, Spain, 5 April 2003 (Magnus Robb). Soft hui calls of a female. 03.008.MR.12312.20T

Perhaps the commonest call of Cetti’s Warbler throughout the year is a rather hard plek. In winter, this is often the only way to detect one’s presence. It differs from similar calls of Savi’s Warbler Locustella luscinioides in being lower-pitched with a slight hint of a spotted woodpecker Dendrocopos.

12) Cetti’s Warbler Cettia cetti Herdade da Alfaróbia, Elvas, Portugal, 10:25, 16 June 2019 (Magnus Robb). Plek calls at close range. Background: Eurasian Blackcap Sylvia atricapilla. 190616.MR.102520.01

There is a rather sparrow-like chink in the repertoire of Cetti’s Warbler that is normally heard in the context of song. Here however is a sequence where a bird used this call without any other song-like sounds before or after. It could easily be mistaken for a sparrow Passer.

13) Cetti’s Warbler Cettia cetti Parc Natural S’Albufera, Mallorca, Spain, 06:00 10 April 2002 (Mark Constantine). A series of chink calls used outside the usual context of song. 008.MC.10230.11T

It has taken me 28 years, and hours spent listening to and recording Cetti’s to content myself, and yet I still think Cetti’s have more sound secrets. I suspect that the reason they have such an array of calls is that the females may use them to show who is the dominant and who the supplicant in their complex web of relationships. As a consequence, Cetti’s Warbler is one of those species that not only has an abundance of calls but that uses them throughout the year.

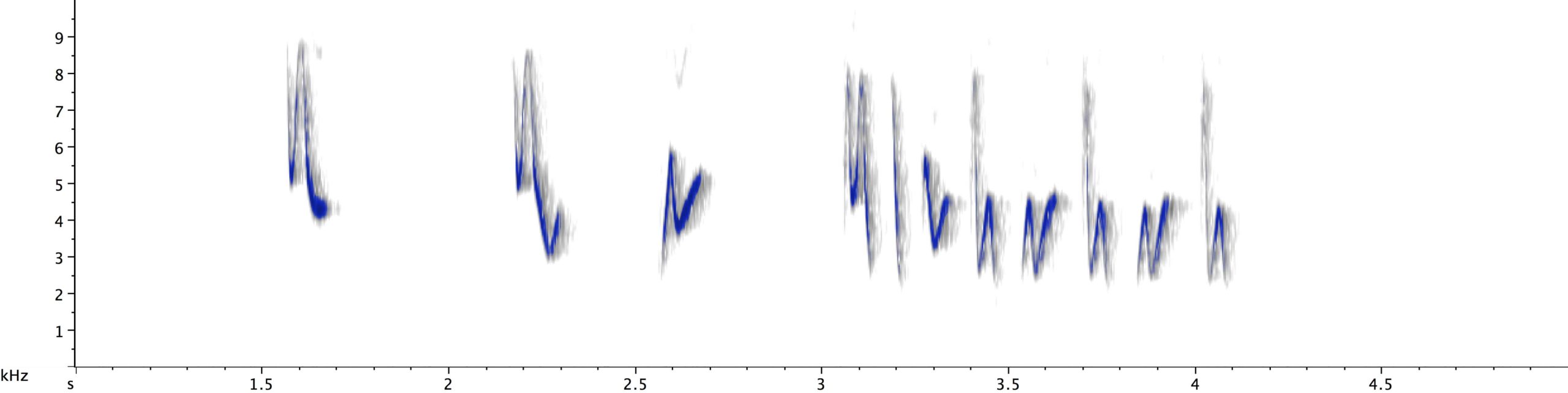

Listen to this plastic song of an immature bird in November. It includes more Savi’s Warbler-like versions of the plek call, as well as some very high-pitched almost bunting Emberiza-like squeaks.

14) Cetti’s Warbler Cettia cetti Leziria Grande, Vila Franca de Xira, Portugal, 10:56, 13 November 2018 (Magnus Robb). Plastic song, presumably from a first winter male. Various less commonly heard calls are embedded within this sequence. 181113.MR.105646.21

Yesterday my friends Jeff and Geri called us on Facetime us to chat about the birds he hears on his daily walks from his house by the river, as he tries to photograph them. We talked of the Common Chiffchaffs Phylloscopus collybita singing everywhere, and how to tell the difference between Eurasian Reed Warbler Acrocephalus scirpaceus song and Sedge Warbler’s A schoenobaenus. I knew Cetti’s breed there but Jeff hadn’t noticed them. Shows that even if you shout, you don’t always get heard.

Constantine & The Sound Approach 2006. The Sound Approach to birding. Poole.

Cramp, S 1992 (ed). The birds of the Western Palearctic. 6. Oxford.

Dooling, R 2004. Audition: can birds hear everything they sing? In: Marler, P & Slabbekoorn, H (eds). Nature’s Music. The science of birdsong. New York.

Bibby, C J 1982. Polygyny and breeding ecology of the Cetti’s Warbler Cettia cetti. Ibis 124: 288-301.

Kroodsma, D 2005. The singing life of birds. Boston.

North, M & Simms, E 1958. Witherby’s Sound Guide. Book re-issued in 1969 with two 33rpm records. London.

Osment, J 2018. The Road to Pelindaba. Poole.