The buzz of ‘nocmig’

Originally published as: Robb, M. & The Sound Approach (2018). BB eye: The buzz of ‘nocmig’. British Birds 111 360–364

As recently as October 2015, I knew of no clear evidence that Goldcrests Regulus regulus and Firecrests R. ignicapilla call while migrating at night. The possibility had occurred to me years before, when I began to question what migrants besides waterbirds and thrushes I might be able to hear in the dark. I knew that most Old World warblers lacked flight calls but that ‘crests’ were different. By day you can see Goldcrests migrating from bush to bush, or flying out boldly across large bodies of water. Without fail, these birds are calling. Tantalisingly, my friend Roy Slaterus described a migrant Firecrest dropping out of the sky on the Dutch coast at dawn in autumn – it too was calling. But do the these two species call at night and, if so, which calls do they use? Might they sometimes fly low enough for a ground-based listener to hear them?

Migrant Goldcrests where I live, near Sintra in Portugal, are scarce, perhaps on a par with Wrynecks Jynx torquilla in the UK, and in some years they are absent altogether. Firecrests are common, but mostly resident. I have been recording nocturnal migration regularly from my back garden since 2009, and for the first six years I had no unambiguous recordings of either crest species to show for it. I was struggling to answer my questions about the crests. Fortunately, by autumn 2015, Nick Hopper was recording night migration at Portland Bird Observatory and Paul Morton was setting up his gear on a rooftop in the old town centre of Poole, also in Dorset, and in the end we cracked it together. Amazingly, I was the first to get one that autumn. On the night of 6th/7th October, early for Portugal, I recorded two ‘sip’ flight calls of a Goldcrest. Despite heralding the start of a decent influx, this was to be my only nocturnal crest that year. Over the following weeks, however, both Nick and Paul recorded many Goldcrests when a great wave of them erupted from Scandinavia. Since then, we have recorded both crests in both countries. While some years produce more than others, between us we have detected them every autumn since. So now there are clear answers to my questions. Yes, they do call at night, using the same calls as migrants by day; and yes we can pick them up.

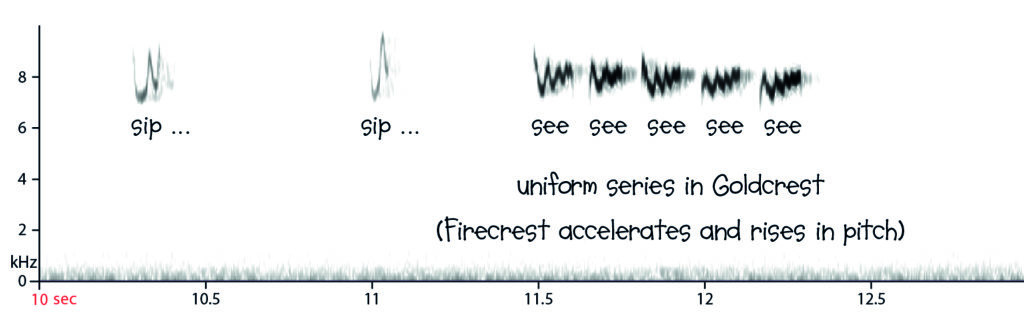

Fig. 1. Goldcrest Regulus regulus, Old Town Poole, Dorset, 01.44 hrs, 30th October 2017 (Paul Morton). Two types of nocturnal flight calls from a passing migrant.

Firecrest Regulus ignicapilla, Martinhal, Vila de Bispo, Portugal, 01.24 hrs, 4th October 2017 (Magnus Robb). Nocturnal flight calls from a passing migrant nearing the sea, apparently about to leave Europe.

By 2017, Paul had been recording for several autumns, and he was familiar with most of the regular UK night flight calls (or NFCs). Then, on the night of 27th/28th October, a strange passerine had him stumped. It sounded like a Robin Erithacus rubecula, but somehow more forceful, showing a curious arched shape in sono- grams. He sent it to me and I recognised it straightaway. In fact I had recorded three in Portugal, six nights earlier. Paul found two more and by the time I replied, he also knew what they were. They were Hawfinches Coccothraustes coccothraustes. It turned out that nocturnal migration enthusiasts were suddenly recording them in numbers, from Azerbaijan to the Atlantic. Prior to last autumn, only Ralph Martin, in Germany, had ever reported having recorded flight calls of Hawfinches at night.

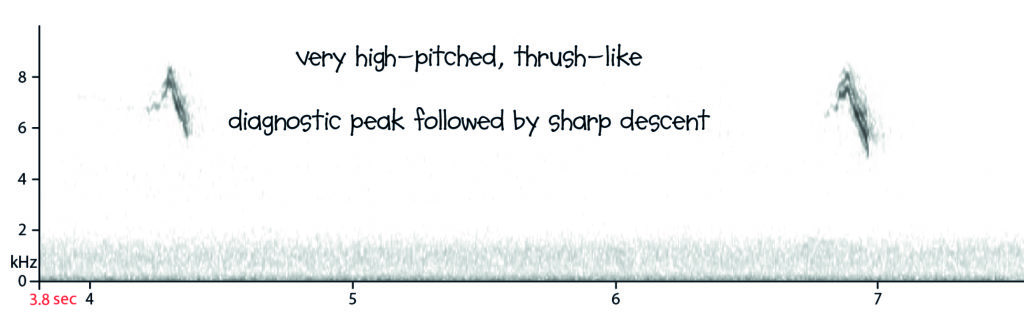

Fig. 2. Hawfinch Coccothraustes coccothraustes, Old Town Poole, Dorset, 01.32 hrs, 28th October 2017 (Paul Morton). Flight calls of a nocturnal migrant.

The delight of the unexpected and the excitement of detecting common but previously incognito night migrants helps to explain what must have been a hundred-fold increase in the number of people recording nocturnal migration in western Europe during the last couple of years. ‘Nocmig’ is in vogue, and even after the novelty wears off, I am sure it will be here to stay, developing in ways we can only imagine just now.

The challenges for a ‘nocmig’ enthusiast include: 1) to record as much as possible from the sky and as little as possible from ground level; 2) to have enough battery power to record many hours, preferably entire nights; and 3) to analyse the recordings accurately and without taking all day. Recording sound quality sufficient for correct identification can be achieved without spending vast sums on equipment. Where you put your gear is just as important. The diversity of species you identify in your recordings depends very much on how well prepared you are to recognise it. Serendipity is the name of the game.

My personal aim is first and foremost to learn, but in the longer term also to help others less experienced than myself. For this I need to make recordings that can serve as clear illustrations. Working for The Sound Approach, I have access to good-quality equipment. I use a Sound Devices MixPre3 recorder connected to a USB powerbank. In my experience, 12500 mAh or more will power the recorder all night. In quiet places with very little wind or ground-level noise, I use ultrasensitive Sennheiser MKH-20 omni- directional mics in a SASS binaural casing (Constantine et al. 2006). Features of the sur- roundings – a natural hollow, a bank or a wall, for example – can help to block out ground-level noise. In noisier places, I use a directional Telinga parabolic microphone, pointing it up at the sky. Both options record in stereo, allowing me to hear movement, which helps to assess the numbers of passing migrants more accurately.

The time-saving trick is to flick through sonograms at an appropriate resolution, say 20 seconds per screen and at 0–8 kHz, as a way of locating the calls. For this I use Raven Pro 1.5 software, but cheaper options include Amadeus Pro and Audacity. Flight calls show up as clearer traces than sounds from ground level, ‘unsmudged’ by reflections from build- ings, trees and other objects, and generally at higher frequencies. Once I find a possible NFC, I listen to it and zoom in if necessary, looking at finer details. If I am unsure about the identification – and believe me this happens a lot – then I ask myself what it sug- gests to me, within the realms of the reason- ably possible. Then I compare it with other recordings of confirmed identification and compare details such as the length, frequency range, shape, etc.

It is important to know what species are more likely to be calling at a given time of year, and to take every opportunity to learn their calls during the day. While some migrants, notably warblers, are silent, many species use the same flight calls day and night. A few, such as chats and flycatchers, use flight calls only at night. At the time of writing there is very little published reference material for European NFCs in particular. The Sound Approach intends to start work on an online NFC guide for Europe in the near future. We have already published a number of blog posts on specific groups, and there are references to these below. For migration flight calls generally, see van den Berg et al. (2003) and Constantine et al. (2012). Exam- ples of most species’ flight calls can also be found on www.xeno-canto.org but beware of possible misidentifications, especially of birds recorded at night.

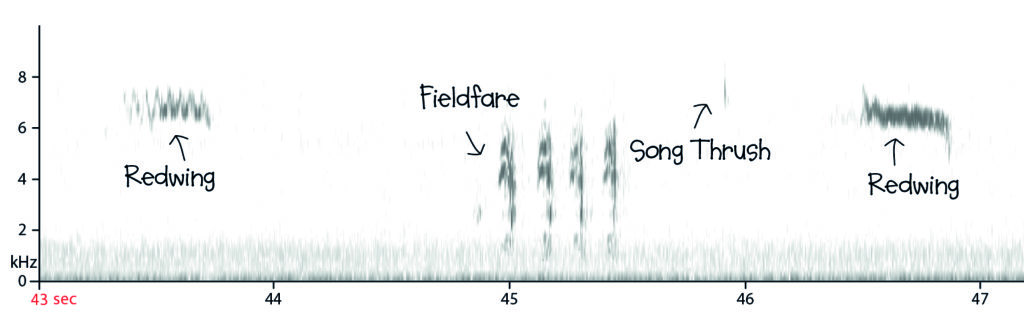

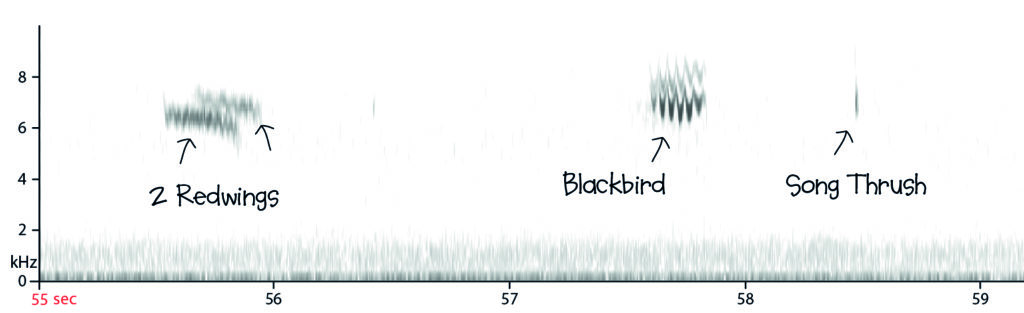

Typical early autumn nocturnal migrants include various herons, waders, rails, Tree Pipit Anthus trivialis and Pied Flycatcher Ficedula hypoleuca; Spotted Flycatcher Muscicapa striata is much less vocal (Robb 2017b). Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana is an outside possibility in the UK, occurring in greater numbers than previously suspected (Robb et al. 2016, 2017). Mid to late autumn is the time of greatest numbers and variety, dominated by thrushes (except for Mistle Thrush T. viscivorus, which rarely calls), Robins and to a lesser extent Skylarks Alauda arvensis. Wildfowl and late waders such as Northern Lapwing Vanellus vanellus and European Golden Plover Pluvialis apricaria are also likely. Spring may also produce some good thrush movements, and is the best time for rails, Little Grebe Tachybaptus ruficollis and, even well inland, Common Scoter Melanitta nigra (Robb 2017a).

Figs 3 & 4. Blackbird Turdus merula, Fieldfare T. pilaris, Song Thrush T. philomelos and Redwing T. iliacus, Old Town Poole, 29th October 2016 (Paul Morton). A night of intense thrush migration is a treat that no birder should be denied.

I love it when my preconceptions take a battering. While Hurricane Ophelia was bringing saffron skies to Ireland and southern Britain last autumn, I was in Shetland, just beyond a front that spiralled anticlockwise into Ophelia’s eye. As it moved slowly north, a powerful but narrow easterly airstream reached Sumburgh, at the south end of the archipelago. Thrush numbers built up there during the day and for the first time in nearly a week conditions looked promising for night migration. At dusk on 17th October, as I set up my equipment, I heard four species of thrush in the space of a minute. I left the site soon after, but my recordings told me what had happened next. The thrushes soon cleared off and were not replaced. A few quiet hours followed while the wind gradually calmed. Odds and ends passed: a Skylark or two, a Golden Plover. Then from midnight onwards there was a real surprise. Meadow Pipits Anthus pratensis started to trickle in, having presumably departed Norway at dusk. The trickle gained momentum, and by the hour before dawn there was a constant stream. While Tree Pipits are long-distance migrants, commonly travelling both at night and during the day, I had only ever recorded a handful of Meadow Pipits at night before, and now there were hundreds. I even picked up my first three nocturnal Rock Pipits A. petrosus, surely belonging to the Scandinavian race A. p. littoralis.

Meadow Pipit Anthus pratensis, Sumburgh Head, Shetland, UK, 05.39 hrs, 18th October 2017 (Magnus Robb). Nocturnal flight calls of a passing migrant. 171018.MR.053900

Better still was a pipit I recorded one night in Portugal in 2010. My first October visit to the tiny island of Berlenga coincided with a big fall. The island has only three ‘trees’, figs in sheltered inlets below the cliffs. Migrants are easy to see there, and so many entertained me within sight of the pier that I failed to climb to the island’s plateau during the first day. That night, however, I climbed to the highest point and sat near the lighthouse for a while, recording nocturnal migration. Pied Flycatchers passed now and then, and I remember a late Ortolan going by. At one point a single sharp and slightly impure, descending call rang rarity bells in my head. I wondered about a Catharus thrush and made a mental note to listen to my recording again after the session, but I forgot. The next day when I recorded and photographed Portugal’s second Blyth’s Pipit A. godlewskii on the plateau, the penny finally dropped.

Blyth’s Pipit Anthus godlewskii, Berlenga, Peniche, Portugal, 23.28 hrs, 12th October 2010 (Magnus Robb). Nocturnal flight call of a vagrant, at the time the farthest west ever.

I still record a few new NFCs in Portugal every autumn, although the learning curve is gradually levelling off. So I take every oppor- tunity to record at night during my travels. Cape May, New Jersey, in late autumn 2017 blew my mind. North American night migra- tion is so much richer than ours, since their warblers all have flight calls, and it is under- standable that American birders are years ahead in learning their NFCs (for example Evans & O’Brien 2002). But Palearctic night migration is well worth the extra patience required, and we are beginning to catch up.

On my return from a recent owling trip to the United Arab Emirates, the discovery of a new nocturnal migrant picked up by the recording equipment had me thrilled. I had been working in the arid Al Hajar Mountains. At dusk my friends and I set up recording gear in three different wadis in the same area, then listened for a few hours before retiring to our accommodation after midnight. A week later, back home in Portugal, I was checking for owl activity during the rest of that night when I came across an unidentified flock of migrants. Partly drowned out by a plane, they took a couple of minutes to pass, triggering vague thoughts of sandgrouse Pterocles and godwits Limosa. I soon eliminated both possibilities. Listening a few more times, I realised I had heard those sounds before, on the mudflats of Barr Al Hikman in Oman: they were Crab-plovers Dromas ardeola. Soon afterwards, I found that they had also passed a second set of my microphones a few kilo- metres farther on, several minutes later and without the plane. How about that! A flock of one of the world’s strangest waders, breeding in tunnels under the sand, recorded taking a short cut from the Indian Ocean to the Persian Gulf from deep inside not just one but two mountain wadis.

Crab-plover Dromas ardeola, Dibba mountains, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, 03.10 hrs, 16th April 2018 (Magnus Robb). Nocturnal flight calls of a passing flock.

There is so much more to tell, and so much more to learn. I am still waiting for my first nocturnal Dotterel Charadrius morinellus or Snow Bunting Plectrophenax nivalis. The challenge is to remain focused, stay realistic, and not be overwhelmed by the many mystery calls recorded. Each one is an opportunity, and if you save it for later, the pleasure of solving it may still be yours.

References

van den Berg, A. B., Constantine, M., & Robb, M. 2003. Out of the Blue. Audio CD & booklet, available online at soundapproach.co.uk/1833-2/

Constantine, M. & The Sound Approach. 2006. The Sound Approach to Birding. The Sound Approach, Poole.

Constantine, M. & The Sound Approach. 2012. Catching the Bug. The Sound Approach, Poole.

Evans, W. R., & O’Brien, M. 2002. Flight calls of migratory birds. CDR, available online via oldbird.org/

Robb, M. 2017a. Common Scoters in strange places. soundapproach.co.uk/common-scoters-strange-places/

Robb, M. 2017b. Nocturnal flight calls of flycatchers, robins and chats. soundapproach.co.uk/nocturnal-flight- calls-flycatchers-robins-chats/

Robb, M., Hopper, N., & Morton, P. 2016. Things that go plik in the night. Part 1. Nocturnal autumn migration of Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana in Dorset, England, and southern Portugal.

Robb, M., Hopper, N., & Morton, P. 2017. Things that go plik in the night. Part 2. Nocturnal migration of Ortolans in Dorset and southern Portugal. soundapproach.co.uk/things-go-plik-night-part-two/