Killian Mullarney

Text by Magnus Robb.

Beneath the Topkapi palace in central Istanbul, Turkey, where the Ottoman sultans used to live, I stop to glance across the Bosporus. On the far side of the channel, a tight flock of about 20 waders flies south into the Sea of Marmara. Raising my binoculars, I expect to see curlews, or something of similar size. But when they emerge from behind a ship, I realise my mistake. Brown-backed and stiff-winged, they power on to the southwest, disappearing into the glare of the afternoon sun. These were Yelkouan Shearwaters, their course straight and wader-like because of the complete lack of wind.

The old Greek name Bosporus means the same as ‘Oxford’ in England or ‘Coevorden’ in the Netherlands. But this is no shallow waterway, and it would take a hardy ox to survive the crossing. The distance from Europe, where I am standing, to Asia, on the other side, is just under 2 km, but twice a year, almost the entire world population of Yelkouan Shearwaters passes through this gap, going to and from the Black Sea. One popular theory holds that the Bosporus was formed around 7600 years ago, when the rising waters of the Mediterranean and the Sea of Marmara breached the 29 km of land separating them from the Black Sea, then a fresh water lake (Pitman & Ryan 1999). The mind boggles. Never mind the deluge, catastrophic torrents of seawater gouging out a 36-124 m deep channel all the way from the Sea of Marmara to the Black Sea. What about the Yelkouans? How long did it take them to discover the new sea? Did they simply follow schools of small fish through the gap, or had they even been visiting the huge freshwater lake for millenia?

Now, in mid-November, Yelkouan Shearwaters are streaming back out; entering the Sea of Marmara, then passing a second gate, the Dardanelles, into the Aegean and beyond, returning to wherever else in the Mediterranean they might breed. Two Yelkouans in the Black Sea were found with rings originating from as far away as Malta (Bourne et al 1988), and some passing through the Bosporus may come from Corsica, Sardinia or the Provence coast of southern France. By contrast, the Strait of Gibraltar at the other end of the Mediterranean seem to be a gate Yelkouans are very reluctant to pass. They were often recorded in the Strait in the 1980s, and observations have been claimed beyond, for example in north-western Spain. But hard evidence in support of Yelkouans in the Atlantic is still lacking (Gutiérrez 2004). Instead, it is Balearic Shearwater that exits through the Strait of Gibraltar. After a breeding season on Formentera, Ibiza, Mallorca or associated islets, Balearics head off west, passing through the Strait from May to July. This east-west migratory divide is perhaps the most striking difference between Balearic and Yelkouan.

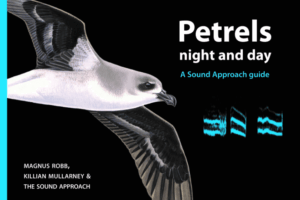

Yelkouan Shearwater Puffinus yelkouan, Bosporus, Turkey, September 2006 (Luc Hoogenstein)

I have only once visited a Yelkouan Shearwater colony, in May 2002. A few weeks after recording Barolo Shearwaters in the Azores, I found myself among Cinereous Vultures Aegypius monachus, Syrian Woodpeckers Dendrocopos syriacus and Eastern Orphean Warblers Sylvia crassirostris in north-eastern Greece. Reluctantly, I tore myself away from the fantastic Dadia forest, close to the Turkish border, and drove west and south. New moon was approaching, and I had finally realised its importance for recording shearwaters. All I had to help me find Yelkouans in Greece was a list of Important Bird Areas (Heath & Evans 2000). The island of Alonissos in the northern Sporades looked like my best bet. Not only were Yelkouans “common” there, but the island was fairly straightforward to reach. Arriving at the quay of Patitiri on the high speed Hellas Flying Dolphin, I bought a map to locate the steepest cliffs on the island. Two hours after sunset I was recording a concert of Yelkouans at the island’s northern end, pointing my parabolic dish down towards caves and crevices about 110 m below. The shearwaters sounded for all the world like great bellows, stoking the fires of hell (CD1-53).

CD1-53: Yelkouan Shearwater Puffinus yelkouan Alonissos, northern Sporades, Greece, around 21:30, 12 May 2002. Probable non-breeders calling in flight around two hours after sunset. 02.025.MR.03135.01

Yelkouan Shearwaters streaming through the Bosporus were once thought to be souls of the damned, and this belief was taken so seriously that there was a prohibition on harming them (Stanley 1902, cited in Warham 1996). Their sombre plumage may partly explain this belief, and perhaps also their infernal calls. But Yelkouans have other associations with the deceased that are calmer, more idyllic and peaceful. In Ancient Greek myth, Alcyone was the daughter of the wind god Aeolus, and wife of Ceyx. Alcyone warned her husband against making a sea voyage to consult the oracle of Delphi. When Ceyx was killed in a shipwreck, Alcyone learned of his fate in a dream, and threw herself into the sea. Out of compassion, the gods changed them both into mythical seabirds called halcyons. When Alcyone tried to make her nest, waves threatened to destroy it. Her father restrained his winds and calmed the waves during seven ‘halcyon’ days each winter, so she could lay her eggs. In the course of two and a half millennia, ‘halcyon’ may or may not have led to modern ‘yelkovan’, the Turkish name now used for the shearwater (Andrew 1990, 1991, Bourne 1990, 1991, Seslisozluk 2007). One of the other meanings attributed to the Turkish word ‘yelkovan’ is ‘spirit of the wind’ (Bourne et al 1988).

Halcyons have also been associated with kingfishers, but the mythical creatures may have been a composite of several real ones, like satyrs or gryphons. If any shearwater can claim, at least in part, to fit the myth, then surely Yelkouan is the best candidate. They spend their entire life in one of the world’s calmer seas, and some attend their colonies in winter. Perhaps the ancient Greeks, seeing them feeding near the shore on calm days, thought there was a magical connection: shearwaters had power over the wind.

Yelkouan Shearwater was first described in 1827 by Giuseppe Acerbi, an Italian ornithologist best known for his writings about Lapland. The specimen he described as Procellaria yelkouan came from the Bosporus, where he must have been informed about the bird’s local name. The species name yelkouan has stuck, but the genus name Procellaria now denotes a group of large, shearwater-like petrels from the southern hemisphere. Balearic Shearwater was not described until the early 20th century (Lowe 1921), but Manx Shearwater was described much earlier, in 1764, by Morton Thrane Brünnich of Copenhagen, Denmark.

The night I visited the colony on Alonissos, the Yelkouan Shearwaters were working their magic, and there was hardly a breath of wind. I could hear hell’s bellows all right, but I could not feel its breath. The shearwaters were calling from the rocks, as well as in flight. The first one in CD1-54 is a male on the wing, and you can hear the vibrato effect caused by its wingbeats, modulating the pitch of its calls.

CD1-54: Yelkouan Shearwater Puffinus yelkouan Alonissos, northern Sporades, Greece, around 21:30, 12 May 2002. The first caller in this track is a male. Note the clear-sounding exhaled note followed by a shorter, harsh inhaled note. 02.025.MR.00341.01

Sexing in Yelkouan Shearwater works in the same way as in Balearic Shearwater. The tone or timbre of the sexes is diametrically opposed: clear in male exhaled notes where the female is harsh, and vice versa for inhaled notes. Bourgeois et al (2007) have discovered an additional and useful rule. They studied sexual differences in the calls in some detail, based on individuals whose sex had been verified by molecular means. The louder, longer exhaled notes in male calls are always higher pitched than the quieter, shorter inhaled ones in females. This means you can sex Yelkouan calls by the pitch of the clearer note, regardless of whether it is inhaled or exhaled. The cut-off point identified by Bourgeois et al was 678.4 Hz, with male exhaled notes always above and females inhaled always below this.

In CD1-55, the first bird to call is a female. Besides the differences in pitch and timbre, her phrases are also considerably shorter than those of the male at the start of CD1-54. Towards the end of this recording, you can hear some insomniac Alpine Swifts Apus melba flying around in the dark. Their loud, excited trills add some higher-pitched devilry to the soundscape.

CD1-55: Yelkouan Shearwater Puffinus yelkouan Alonissos, northern Sporades, Greece, around 21:30, 12 May 2002. The first caller in this track is a female. Note the harsh-sounding exhaled note followed by a shorter, clearer inhaled note. Background: Alpine Swifts Apus melba 02.025.MR.00019.00

Male calls are far more variable than female calls, especially in the length of the exhaled note. When they are advertising their burrows, males need to be conspicuous and individually recognisable so that females can choose among them from the air. The down side of this individual variation is that it blurs the distinction between Balearic and Yelkouan Shearwaters. There is a great deal of overlap between these species in the lengths and frequencies of their calls.

Hearing differences between the two species is not straight-forward. If you compare them in the recordings accompanying this book, I am sure you will agree that they sound very similar. I confess that until I did a thorough analysis, I had no clear idea how to tell them apart. But after a couple of days comparing sonagrams, measuring lengths and frequencies of calls given in flight, I found that, on average, their calls were not the same.

Yelkouan Shearwater, the smaller bird, averages higher pitched than Balearic Shearwater. Male exhaled notes of Yelkouan in my sample were on average 9.5% higher, and female inhaled notes 6.8% higher than same sex Balearic. A bigger surprise was that Yelkouans tend to have longer calls. Male phrases were on average 7%, and females phrases 14.6% longer than in Balearic. These differences in frequency and timing proved to be statistically significant (George Sangster in litt).

Yelkouan Shearwater Puffinus yelkouan, Viareggio, Toscane, Italy, 8 September 2007 (Daniele Occhiato)

Female calls of Balearic Shearwater differ slightly in rhythm from those of female Yelkouan Shearwater, and this was something I might have picked up by listening. In female Balearic, the exhaled note averages just a third longer than the inhaled note, but in female Yelkouan it averages nearly two thirds longer. Imagine the females dancing to their own rhythm. If I may exaggerate a little, female Balearics march, while female Yelkouans waltz. Compare the female Balearic at 0:05-0:10 in CD1-50 (two roughly equal ‘beats to the bar’), to the female Yelkouans at the start of CD1-53 and CD1-55 (long-short rhythm, roughly approximating to three ‘beats to the bar’). In reality of course, individual shearwaters are free spirits, and not all of them dance to the same rhythm. But if you listen to females of the two species for any length of time, you will find that this difference works for many.

Balearic and Yelkouan Shearwater have similar tastes in breeding habitat, preferring caves, fissures and screes, with a bit of soil to burrow in. They avoid nesting on bare rock, unlike Scopoli’s Shearwater Calonectris diomedea, which can tolerate a lack of soil. Breeding starts much earlier than in Manx, because Mediterranean waters are most productive in the colder half of the year (Zotier et al 1999). Balearic lays in late February or early March (Miguel McMinn pers comm), and Yelkouans in the south of France lay nearly a month later (Bourgeois & Vidal 2005). Breeding so early allows them to finish rearing their single nestling before food becomes scarcer in the Mediterranean summer. It also explains why Balearics turn up in northern Europe so early, even while Manx are still incubating in June and July.

Yelkouan Shearwater Puffinus yelkouan, Bosporus, Turkey, September 2006 (Luc Hoogenstein)

One of the peculiarities of Balearic and Yelkouan Shearwaters is that, unlike Manx, they are primarily coastal feeders. This is particularly true of Balearics, which rarely forage more than 15 km from the shore. Yelkouans venture slightly further afield, but still prefer to feed in waters less than 100 m deep (Yésou & Patterson 1999). In northern European seas, this niche is exploited by auks, but shearwaters have no such competition in the Mediterranean (Zotier et al 1999). Some of the most nutrient-rich coastal areas include estuaries; I have seen large flocks of Yelkouans off the Nestos Delta in northern Greece. One of the fish Yelkouans prey on, the Black Sea Sprat Clupeonella cultriventris, migrates to the lower reaches of rivers to spawn. In late summer and autumn, a few Yelkouans apparently follow them into larger rivers such as the Danube (Nankinov 2001). In the mid-19th century, one even flew up the river as far as Vienna, and made it onto the Austrian national list (Bauer & Glutz von Blotzheim 1966).

Should you start thinking of Yelkouan as a lightweight among shearwaters, with a cushy life in a largely storm-free Mediterranean, think again. Spare a thought for the ones that winter in the north and east of the Black Sea, where coastal waters may freeze in winter. They may even prefer severe winters, when there can be large concentrations of European Anchovies Engraulis encrasicolus along the eastern Black Sea coast (Nankinov 2001). At the same time as Yelkouans are braving this cruel continental winter, Scopoli’s, Cory’s C borealis and Manx are basking in the southern hemisphere summer, and most Balearics are spending the winter in mild conditions off the north-eastern coast of Spain.

‘Mediterranean shearwaters’: known breeding distribution.

Recording locations indicated by arrows.

Balearic Shearwater Puffinus mauretanicus (red dots).

Recordings: Mallorca, Balearic Islands.

‘Menorcan shearwater’ Puffinus mauretanicus / yelkouan (purple dot).

Recordings: La Mola, Menorca, Balearic Islands.

Yelkouan Shearwater Puffinus yelkouan (blue dots).

Recordings: Alonissos, northern Sporades, Greece.

Yelkouan Shearwaters breed mainly in central and eastern parts of the Mediterranean. The Aegean is one of their strongholds, but they also breed in the Adriatic, the Sicilian channel, on islets around Corsica, Sardinia and Sicily, and off the southern coast of France. Strangely, breeding in the Black Sea has been documented only once (on an islet belonging to Bulgaria; Snow & Perrins 1998), despite Yelkouans being numerous there during the breeding season. In some countries, notably Turkey, breeding is very poorly documented, and this is why BirdLife International (2006) estimated the world population at anything between 14 750 and 52 300 pairs.

In 2006, a very large colony estimated at thousands of pairs was discovered on the Italian island of Lampedusa between Sicily and Tunisia (Andrea Corso in litt). This is quite exceptional; in keeping with most other Mediterranean seabirds, Yelkouan colonies are generally no larger than a few hundred pairs. The Mediterranean is not a particularly productive sea, but there are very rich fishing grounds in the Sicilian channel.

Some 875 km to the north-west of Lampedusa, a fortified peninsula called La Mola on the Balearic island of Menorca forms the easternmost point of Spain. About 10 years ago, Rafael Meliá López and his family moved there from the nearby town of Mao, and became the only inhabitants of the peninsula. Every morning, Rafael and his family are the first Spaniards to greet the rising sun.

With its strategic position, overlooking a sizeable chunk of the Mediterranean, Menorca has always attracted military attention. Even the Turkish navy, all the way from the Bosporus, found reason to destroy Mao and the other main town, Ciutadella, back in the 16th century. Other attackers approached through the Strait of Gibraltar. In 1708, the British captured Mao during the War of the Spanish Succession, and founded a naval base there. The French pinched it from the British twice, before it was ceded to Spain in 1802. The Spaniards had no intention of losing it, so they built a series of impressive defences. However, this would not be sufficient to save them from internal trouble and strife.

When Arnoud, Miguel and I went to Menorca in March 2007, we paid Rafael a visit, and he told us a remarkable story. At the beginning of the Civil War in 1936, the fort was occupied by a garrison whose officers wanted to join Franco on the Nationalist side. However, the lower ranks stayed loyal to the Republic, and they captured and imprisoned 87 of their superiors in the fort. One dark night, all the officers were shot. Among the dead was the second in command of the naval base of Mao. His wife, fearing for her life, tried to take a boat to the mainland, hoping to cross the front into Nationalist territory. She was caught just before boarding, with documents from the naval base in her possession. At this point in the story, we enter the realms of myth. Nobody disputes that she was taken to La Mola and thrown over the cliff. Some say she was shot first and then thrown. The Nationalist version, embellished for propaganda purposes, had her tortured by the Republicans first, thrown over the cliff alive and put out of her misery by a passing fisherman from the deck of his boat three days later.

After the war, with the fort back in Nationalist hands, a steady stream of conscripts from all over Spain came to do their national service. Many from central Spain had never seen the sea. Disembarking on their arrival from Barcelona, some knelt down on the shore to quench their thirst. All over the world, newly recruited or conscripted soldiers are subjected to imaginative initiations, and Menorca was no exception. The regular soldiers at La Mola would wait for a particularly dark night, then take the newcomers outside, at 03:00 or 04:00 in the morning. Reaching the little cross at the top of the cliff, they told them the story of the naval officer’s wife. It would not be many nights later before one of the conscripts, serving on watch duty, reported seeing her ghost. If the darkness of the night and the sound of wind and waves were not enough to fire the imagination, then what about the weird cries of shearwaters coming from the base of the cliffs? With every new batch of conscripts, the ghost’s notoriety grew. Sometimes, when half-visible ‘spirits’ sailed past, their appalling cries echoing from the cliffs, rifle shots were even fired into the night.

La Mola, Menorca, Balearic Islands, 12 March 2007 (Arnoud B van den Berg). The shearwaters breed mainly in caves and crevices where the cliffs meet the steep slopes. This is where CD1-56 and CD1-57 were recorded.

From the isthmus separating La Mola from the rest of Menorca, we walked round to the cliffs on the north side, then clambered over the fallen rocks on the steep slopes below. Arnoud decided to wait near the entrance of a funnel shaped cave. It had a well-worn little path along one side, leading to a bottleneck seven metres further in where no man could follow. Miguel brought me to another hotspot, some way further along the cliff base, where he showed me some small caves and crevices where the shearwaters nest.

The weather had been rough for several days, and we were really unsure what to expect. Menorcan shearwaters breed to a schedule that runs two or three weeks later than Mallorca, so these birds would not lay until the end of March. When it was already quite dark, the first shearwater landed close to where I was sitting. It scurried over the ground towards me, then disappeared into a narrow crevice just to my right where I lost it in the darkness. Over the next 15 minutes or so, a procession arrived, all doing exactly the same thing, and all remaining silent.

Eventually, I began to hear faint cries coming from the depths of the crevice beside me. Realising that this was not going to be a night of shearwater-filled skies, I decided to cut my losses and see if I could record anything down below. The crevice was really a narrow pit, only just wide enough for me to fit in, and the bottom turned out to be two metres under the ground. As I squeezed myself and my equipment through the gap, I wondered if I would be able to get back out. The seaward side was formed by a huge block of rock. Underneath it, there seemed to be enough room for several nests, and I could make out three shearwater-sized holes. I was unable to get my head down there to look through them, so I crouched as low as I could, positioned the microphones in one of the holes, and listened with headphones to what was going on.

Menorcan shearwater’ Puffinus mauretanicus / yelkouan, upon arrival at cave, La Mola, Menorca, Balearic Islands, 12 March 2007 (Arnoud B van den Berg)

Every minute or so, a half-hearted call from one of the birds provoked a weak response from another, and there were enough little grunts and groans to tell me that at least they were not falling asleep. After quite some time, three latecomers arrived in fairly quick succession. I could hear the flurry of wings, followed by a clambering of claws, and braced myself for what I knew would happen next. Sure enough, each time one dived into the crevice, it landed on top of my head. They soon recovered their wits, scampered down over the large foreign object, and disappeared into one of the three holes. Their arrival helped to liven up proceedings down below, and finally, when I had been down there for the best part of two hours, I recorded some vigorous interchanges between males and females of several different pairs (CD1-56).

‘Menorcan shearwater’ Puffinus mauretanicus / yelkouan, upon arrival at cave at night, La Mola, Menorca, Balearic Islands, 12 March 2007 (Arnoud B van den Berg). A different individual to the one above.

CD1-56: ‘Menorcan shearwater’ Puffinus mauretanicus/yelkouan, La Mola, Menorca, Balearic Islands, 22:44, 12 March 2007. Males and females calling beneath a huge rock, two metres under the ground. 070312.MR.224456a.00

When I caught up with Arnoud, sometime after midnight, he also had a story to tell. The cave had been recommended to him by Miguel, who thought it would offer good oppor-tunities for photography. When darkness fell, at least 40 shearwaters landed, one by one, at the entrance to the cave. They scurried up the little path along the wall, losing no time in heading towards the bottleneck at the back. Arnoud was fully prepared, armed with camera and flashlight, and he photographed about half of the astonished shearwaters as they made their way towards their nests.

‘Menorcan shearwater’ Puffinus mauretanicus / yelkouan, arriving at cave after dark, La Mola, Menorca, Balearic Islands, 12 March 2007 (Arnoud B van den Berg)

Like me, Arnoud heard no flight calls that night. In fact, he did not hear calls of any description. Every single shearwater that shuffled into the far depths of the cave simply disappeared without a trace. Remember I wrote that there was a bottleneck where no man could follow? Well, Arnoud is not one to leave anything to chance. By the time I found him he was a bit dishevelled, and his green jacket was stained a suspicious reddish brown. Later, we stopped at a 24-hour petrol station to buy a drink and a sandwich, and he disappeared without trace for a long time. When he eventually emerged from the lavatory, his hair was combed, his jacket damp and green again, and he had a satisfied twinkle in his eye. Nevertheless, our hire car smelled strongly of petrel when we both nodded off to sleep.

Breeding of shearwaters on Menorca was suspected for a long time, but first documented only as recently as the 1990s. Subsequent fieldwork soon led to the realisation that Menorcan shearwaters are different from typical Balearic Shearwaters. For a start, Miguel and Ana, who probably know them better than anyone else, tell me that not just some, but all of the Menorca birds have a paler, essentially Yelkouan-like plumage. In measurements, they average smaller than Balearics from Formentera, Ibiza and Mallorca (Genovart et al 2007). Ana has commented that she needs two hands to hold a Balearic from Mallorca, but a Menorcan shearwater will easily fit in one.

Arnoud’s photographs of about 20 individuals in the cave confirmed that these shearwaters essentially look like Yelkouans. This applies not only to their plumage: they also have a more Yelkouan-like head-shape, with a slightly steeper forehead. So are they in fact Yelkouans? Before genetic work was carried out, this was where Miguel was putting his money. When 10 individuals were trapped in ‘Arnoud’s cave’ at La Mola, and their mtDNA analysed, five were of a Balearic genetic type and five appeared to be Yelkouans (Genovart et al 2005). There was a 1.6% sequence divergence between the two groups, lower than the 2.2-2.9% difference previously reported between Balearics from Mallorca and Yelkouans from the eastern Mediterranean (Heidreich et al 1998). So Genovart et al (2005) concluded that the Balearic and Yelkouan Shearwaters were breeding side by side in the same cave.

Several observations argue against this apparently straight-forward interpretation of the genetic results. Miguel has not found a single ‘classic-looking’ Balearic Shearwater during his fieldwork at La Mola or elsewhere on Menorca. Menorcans are not only homogenous in appearance; they also breed in synchrony, laying in late March or early April, about three weeks later than Balearics from Mallorca and closer to the breeding schedule of Yelkouan Shearwater. When three Menorcans were satellite tagged, they flew into Yelkouan territory off the south of France (Ruiz & Martí 2004), rather than the normal feeding grounds of Balearic off the eastern coast of Spain (Louzao et al 2004). Unfortunately, nothing is yet known about where Menorcan shearwaters go outside the breeding season, but I would not be at all surprised if they head for the Bosporus.

In a follow-up study, 24 birds were trapped at La Mola, of which 11 had Balearic Shearwater, and 15 Yelkouan Shearwater mtDNA (Genovart et al 2007). Birds of both genetic types were measured and found not to differ in size. Both were significantly smaller and more variable in size than Balearic of the same sex from the rest of the archipelago. Curiously, Genovart et al (2007) lumped the entire Menorcan population under Balearic, despite their smaller size and the majority of Yelkouan genotypes.

My own approach to this problem was to make some recordings. Part of the reason for our visit to La Mola was to find out which species Menorcan shearwaters most resembled in their voice. But their behaviour on the night of our visit gave me a problem. All the Menorcans I recorded were in crevices under the ground, while I had only recorded Yelkouans in flight. Unfortunately, shearwaters in burrows often call differently compared to shearwaters in flight. The physical effort of calling may help to explain why. Mackin (2004) discovered that there was a trade-off between frequency, length and loudness in male Audubon’s Shearwater calls. Louder, higher pitched calls tend to be shorter, while quieter, lower calls are longer and often contain more notes. More air is expelled when producing higher, louder notes, so they tend to be shorter. Flight requires effort, even in shearwaters, putting an additional strain on the lungs. Presumably, when more oxygen is needed to power the wings, this affects length, loudness and pitch.

When I compared calls of Balearic Shearwaters in flight and in burrows, the frequency was considerably lower and the phrases were much longer in burrow calls. Sometimes as an outburst died down, the exhaled notes broke down into several very short ones, something I have also heard from Balearic Shearwaters in burrows, but never from Balearic or Yelkouan in flight. You can hear Menorcans doing this several times in CD1-57. For example, the first male call series breaks down at 0:08.

CD1-57: ‘Menorcan shearwater’ Puffinus mauretanicus/yelkouan, La Mola, Menorca, Balearic Islands, 22:58, 12 March 2007. Interchanges between several duetting pairs beneath a huge rock, two metres under the ground. 070312.MR.225800.00

When I compared shearwaters from Menorca with Balearic Shearwaters, the rhythm and length of the calls were very similar in both groups. However, there were considerable differences in frequency. Menorcans were much higher pitched than Balearics from Mallorca, both in male exhaled and female inhaled notes. The difference was 14% in males, but as much as 31% in the very small female sample. In frequency at least, Balearic and Menorcan in burrows seem to differ in the same way as Balearic and Yelkouan in flight. Perhaps Menorcans and Yelkouans are both higher pitched than Balearic because they are both smaller. It would be interesting to compare more individuals of all three groups, including Yelkouan Shearwaters, and also to compare their calls in flight.

What exactly would the world lose, if the ‘Menorcan shearwater’ became extinct? Their plumage, smaller size, feeding ecology, breeding phenology and perhaps their sounds argue that they are Yelkouan Shearwaters. Several experienced birders, seeing Arnoud’s photographs, were adamant that was what they were. But the presence of both Balearic and Yelkouan mtDNA puts a spanner in the works. Simply lumping them with Balearic Shearwater, as Genovart et al (2007) did, seems the least satisfactory solution of all. A great deal of effort has been spent, comparing Menorcans with 89 Balearic Shearwaters from the rest of the archipelago. But so far, their genes have been compared with just four gene sequences of Yelkouan Shearwater, collected on Crete at the other end of the Mediterranean (Genovart et al 2007, Heidrich et al 1998). In order to gain a clearer picture of shearwater diversity in the Mediterranean, Yelkouan genes from throughout the breeding range should be sequenced. As an important first step, Menorcans should be compared with their neighbours on the southern coast of France.

‘Menorcan shearwater’ Puffinus mauretanicus / yelkouan, after landing near cave at night, La Mola, Menorca, Balearic Islands, 12 March 2007 (Arnoud B van den Berg)

The fortress of La Mola was only built in the 19th century. During the few hundred years before that, successive waves of military invaders came from the east, some from as far as the Bosporus, while others arrived from the west, beyond Gibraltar in the Atlantic. Expand the time frame to a million years, with a succession of Ice Ages, and it is not difficult to imagine shearwaters doing the same thing. Probably, the Menorcan shearwater population owes something to Balearic and Yelkouan Shearwaters, a result of colonisations from either side. They may have hybridised on Menorca in the past, but there is no evidence that they do so at present (Genovart et al 2007). The answer to the question of who got there first is lost in the mists of time, but there are suggestions that a Yelkouan-like shearwater may have lived there for at least a few thousand years.

Not long ago, a tibiotarsus of a small Puffinus shearwater was found in Upper Pleistocene deposits from a cave near Ciutadella, at the western end of Menorca (Seguí et al 1998). Miguel helped to translate the Catalan paper for me, and put the information into context. The bone could be dated to before 1930 BC, because it was found with remains of the endemic Cave Goat Myotragus balearicus, a species that became extinct shortly after human colonisation. It belonged to a shearwater somewhat smaller than those breeding on Menorca in our time. Miguel commented that size may have varied over the course of millennia, depending on the availability of food. This has been observed on the westernmost Balearic island of Ibiza, where shearwater remains are very common.

What a sad end it would be, if the shearwaters of La Mola were wiped out, before we had really worked out what they are. Cats are already doing their best to deprive us of the opportunity. When we arrived at the cave where Arnoud was to spend much of the night, feathers from a recent kill were strewn over the slopes outside. Sadly, later in the 2007 breeding season, no nestlings could be found in this cave. Miguel is hoping to build fortifications that will keep cats away from the colony, if the local government will allow it. He will not be needing artillery and ramparts. A sturdy, well-positioned fence should be enough to keep them out.