Starting in the late 1980s, the young Portuguese scientist Luís Rocha Monteiro studied mercury pollution in the marine environment of the Azores. After a few years, he recruited the help of seabirds. From mercury concentrations in their plumage and regurgitations of food, he was able to infer the health of the rest of the ecosystem. Among the birds he studied were band-rumped storm petrels Oceanodroma, which had only recently been proven to breed in the Azores.

Monteiro soon discovered that there were two populations in the islands, one present in the hot season (March to September) and the other in the cool season (August to March). During the early autumn, adults of the cool-season population could often be found in the very same burrows where nestlings of the hot-season population were still growing up. Striking differences in their mercury levels led Monteiro to believe that the two populations might differ in their feeding ecology, and subsequent research showed that they also differed in morphology and egg dimensions. Hot-season birds were smaller in most body measurements, particularly weight, but had longer tails, and proportionally longer wings. A detailed paper was published, raising the exciting possibility that hot- and cool-season populations in the Azores might be cryptic species (Monteiro & Furness 1998). Tragically, Monteiro never had the opportunity to follow the story through. He died in a plane crash on the island of São Jorge in December 1999, when he was still in his late 30s.

Eight years after his death, the dust is still far from settling over Monteiro’s discovery, and the number of different types of band-rumped storm petrel in the North Atlantic has risen to four. They form a classic example of a group of birds whose diversity went unnoticed due to similarity in plumage, despite differences in measurements, the timing of their annual cycle, and DNA. For us it has been a real adventure obtaining sound recordings of each band-rumped and listening to vocal differences. These are so clear that they readily support any appeals for an increased level of conservation for each one. Collectively, they can be referred to as ‘band-rumped storm petrels’. Madeiran Storm Petrel O castro is the hot-season breeder of the Madeiran archipelago, Selvagens and the Canary Islands. Cape Verde Storm Petrel O jabejabe breeds only in the Cape Verde Islands. Monteiro’s Storm Petrel is the hot-season breeder of the Azores, named after its discoverer Luís Monteiro; a formal description of this new taxon will be published shortly (Bolton et al 2008). Grant’s Storm Petrel (not yet formally described) is the cool-season breeder of the Azores, Berlengas, Canary Islands, Madeiran archipelago and Selvagens. This name was suggested by Steve Howell in conversation, in memory of the late Peter Grant who died in 1990.

Killian Mullarney

Text by Magnus Robb.

present as a breeding bird from March to September in the Azores.

At Ponta da Barca, the north-western point of Graciosa in the Azores, a lighthouse shines onto a tiny islet shaped like a whale. Shortly after dark on 25 May 2007, before the Roseate Terns Sterna dougallii had settled down for the night, Killian and I could hear chatter calls of Monteiro’s Storm Petrels displaying over this islet. Because of the distance, and the surf crashing on the rocks below, quieter parts of their calls were inaudible, but what I could hear sounded unlike any band-rumped storm petrel I had listened to before.

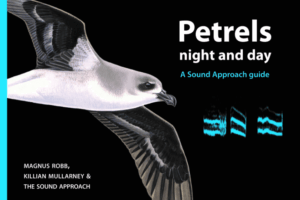

Presumed Monteiro’s Storm Petrels, south-east of Graciosa, Azores, 26 May 2007 (Killian Mullarney)

We spent the next three nights on nearby Praia islet, and I had ample opportunity to hear Monteiro’s Storm Petrels at close range. The best recordings were made on the last night, while sheltering from a strong westerly wind on a broad ledge of the island’s eastern cliffs. A three-quarter-lit moon was bright enough to silence all but a few of the island’s Cory’s Shearwaters. One of these hefty birds startled me when it landed on my knee, digging its claws into the top of my resting hand to steady itself. It sat there happily for a few seconds, until I reached slowly for my camera, when it bolted off into the night. Another mute Cory’s, perhaps buffeted by a strong gust, flew straight into a sheer section of cliff. “Tough as old boots”, said Killian, and we laughed as it fell into a heap beside us, then scurried off into a crevice. But the moon could not suppress the Monteiro’s. As the waves below shimmered in the moonlight, little dark shadows danced to their own cries, tracing wind eddies just below the edge of the cliff (CD2-47).

CD2-47: Monteiro’s Storm Petrel Praia islet, Graciosa, Azores, 22:40, 28 May 2007. Chatter calls of presumed males and females in flight, recorded from a cliff ledge on the eastern side of the islet. Background: Cory’s Shearwater Calonectris borealis. 070528.MR.224009a.00

Monteiro’s Storm Petrels breed only in the hot season in the Azores, and they sound quite different from cool-season Grant’s Storm Petrels. Playback studies have shown that Monteiro’s do not recognise Grant’s as potential mates (Bolton 2007). Genetically, Monteiro’s are distinct from any other population, and Friesen et al (2007) estimated that they last shared a common ancestor with Grant’s 110 000 to 180 000 years ago. A paper is currently in the works (Bolton et al 2008), in which Monteiro’s Storm Petrel will be described formally as a new species. For the sake of clarity, I have adopted this vernacular name here already, believing it is infinitely preferably to ‘hot-season Azores Madeiran Storm Petrel’, but the scientific name cannot be used until it has been published.

[update: In Bolton et al 2008, Monteiro’s Storm Petrel was formally described as Oceanodroma monteiroi]

Luis Monteiro, Graciosa, Praia, Azores, September 1993 (Robert Furness)

Mark Bolton, the lead author in the description of the new species, has already had a major impact on its conservation. Drawing on a grant awarded to Monteiro, Bolton and friends hid rows of artificial nest boxes under the rocks in the higher parts of Praia islet. These proved to be a great success, leading to a 28% increase in the size of the colony and a 2.9 times increase in breeding success in just two years, compared to birds using natural sites (Bolton et al 2004). CD2-47 was recorded on a cliff ledge underneath part of this ‘hotel’, where there was a high density of storm petrels calling in a limited area.

Praia islet, seen from Graciosa, Azores, 26 May 2007 (Killian Mullarney). CD2-47 to CD2-52 were recorded there.

Monteiro’s Storm Petrels have the simplest chatter calls of any Oceanodroma in the North Atlantic. There are typically just four to six notes, compared to the nine of Grant’s and nine or more of Leach’s Storm Petrels. In contrast to Grant’s, there are no l o n g -short, l o n g -short contrasts in the final flourishes, and in Monteiro’s these are a series of one to three yelps. In the middle section, Monteiro’s tends to have just one note, or even none at all. Sexing in Monteiro’s is presumed to be the same as in other band-rumped storm petrels, with males sounding clear and females harsh. However, until this has been confirmed for Monteiro’s, the sexing of the examples should be regarded as provisional. CD2-48 starts with a loud chatter call of a male, ending with two yelps. CD2-49 starts with a chatter call of a female, which ends with three yelps.

CD2-48: Monteiro’s Storm Petrel Praia islet, Graciosa, Azores, 22:40, 28 May 2007. Chatter calls in flight, starting with a loud call of a presumed male. Background: Cory’s Shearwater Calonectris borealis. 070528.MR.224009b.00

CD2-49: Monteiro’s Storm Petrel Praia islet, Graciosa, Azores, 22:40, 28 May 2007. Chatter calls in flight, starting with a loud call of a presumed female. Background: Cory’s Shearwater Calonectris borealis. 070528.MR.224009c.01

Presumed Monteiro’s Storm Petrels, south-east of Graciosa, Azores, 26 May 2007 (Killian Mullarney)

Not all calls given by Monteiro’s Storm Petrels in flight are chatter calls, and sometimes males give short bursts of aerial purring too. An example of one doing this can be heard in CD2-50, at 0:01, 0:05, 0:32 and 0:47. The flourish is much the same as in a chatter call, although there are just one or two yelps at the end. In CD2-50, the male giving aerial purring calls alternates them irregularly with normal chatter calls, a pattern I have also heard from other band-rumped storm petrels. You can hear some more examples of aerial purring calls in the other recordings of Monteiro’s.

CD2-50: Monteiro’s Storm Petrel Praia islet, Graciosa, Azores, 22:35, 27 May 2007. Aerial purring calls and chatter calls of a presumed male. Background: Cory’s Shearwater Calonectris borealis and Common Tern Sterna hirundo. 070527.MR.223536.01

More often, purring emanates from crevices and burrows under the ground, where it is heard in continuous sequences. Purring of Monteiro’s Storm Petrel differs from that of Grant’s Storm Petrel in having fewer loud notes in the flourish at the end of each breathing cycle. Typically, there is just one yelping note at the end, similar to the first yelp at the end of a chatter call. Grant’s, on the other hand, typically has three or four notes at the end of each purring cycle. In CD2-51, you can hear a male and female Monteiro’s purring together in a burrow. Only the male is heard at the start, but the female joins in from about 0:19 with a harsher version of the same call. As in CD2-45 (Grant’s), there is clearly some interaction going on, with each bird taking its turn to ‘flourish’. The male and female never end a cycle at exactly the same time.

CD2-50: Monteiro’s Storm Petrel Praia islet, Graciosa, Azores, 00:11, 28 May 2007. Purring calls of a presumed pair in a burrow. At the end, the female gives two chatter calls and the male one. Background: Cory’s Shearwater Calonectris borealis and Common Tern Sterna hirundo. 070528.MR.01127.00

CD2-45: Grant’s Storm Petrel Farilhão Grande, Berlengas, Portugal, 22 September 2003. A presumed male and female purring together as a ‘duet’, taking turns to deliver the final flourish. Background: Cory’s Shearwater Calonectris borealis. 03.036.MR.00000b.00

The ‘hotel’: artifical burrows which have greatly increased the breeding success of Monteiro’s Storm Petrel, Praia islet, Graciosa, Azores, 27 May 2007 (Magnus Robb). The round concrete roof can be lifted to examine the nest.

A male and female can also be heard purring in the background, slightly to the right, in CD2-52, while a much closer male also purrs intermittently on the left. Just before I pressed the record button, a male had landed left, next to the microphones, apparently attracted by all this purring. You can hear his loud chatter calls, first to the left, then to the right, as he paced around the microphones. Meanwhile, I was sitting just a metre away, hoping the sound would not distort at such close range. Purring is just as attractive to Monteiro’s as it is to other storm petrels, and indeed Bolton et al (2004) used playback of purring, powered by a solar panel, to speed up occupation of the artificial colony.

CD2-52: Monteiro’s Storm Petrel Praia islet, Graciosa, Azores, 23:14, 27 May 2007. Purring calls of two presumed males and a presumed female had just attracted a displaying male down from the sky. Its chatter calls are heard on either side of the microphones as it paces about outside the row of artificial nest boxes. Background: Cory’s Shearwater Calonectris borealis. 070527.MR.231422.00

These recordings were made during the last week of May, at a time when some of the nests already contained eggs. The first adults on Praia islet arrive at the end of March, and Monteiro’s Storm Petrels have the colony to themselves until early August when the first Grant’s Storm Petrels arrive. Monteiro’s lay from May until early July, fledging by mid-September, while Grant’s lay from about October to early December and fledge over a much more protracted period, from about January until March or even April (Bolton et al 2008, Granadeiro et al 1998b, Monteiro & Furness 1998).

One of the consequences of breeding four to five months apart is that Monteiro’s and Grant’s Storm Petrels are out of sync in all other aspects of their annual cycle. During the period when adults of both populations are present at the colony, moult is the best way of telling them apart (Bolton et al 2008). As in most storm petrels, adults of each population start moulting their primaries towards the end of the breeding season, and continue through much of the time they are absent from the colony. Monteiro’s start their primary moult in late summer, just as the very last Grant’s are completing theirs. Moult has been used to show that adult Monteiro’s visit the colony into late September and exceptionally even into October. At sea, moult may be somewhat less reliable for identifying individual storm petrels, because one-year-olds of some species are known to moult several months earlier than adults. Because they have only been trapped and examined at breeding colonies, which they do not visit until they are two years or older (Bried & Bolton 2005), nothing is known yet about the moult of one-year-old Monteiro’s.

When Killian and I watched Monteiro’s Storm Petrels during two evenings out at sea in the last week of May, none of them showed any primary moult. The only storm petrels we saw that did, turned out to be two early Wilson’s Storm Petrels Oceanites oceanicus. We were fortunate that Verónica Neves, who organised our trip, knew an excellent skipper called Rolando Oliveira with a spacious, fast inflatable, often used for whalewatching. When we asked him if he had seen any storm petrels recently, he brought us to an area several kilometres south-east of Graciosa, some distance beyond the other main Monteiro’s colony on Baixo islet.

Monteiro’s Storm Petrel: known breeding distribution (red dots).

Recording location indicated by arrow: Praia islet, Graciosa, Azores.

Our initial encounters with Monteiro’s Storm Petrels were brief, but exciting. The first one was in travelling mode, shearing in neat, regular arcs like a miniature shearwater. Rolando swung the boat round and we followed it, with Killian trying to steady his camera as the boat bounced along on the waves. Despite all the movement, I could make out a fork in the tail, and Killian’s photographs showed this too. Later, when we encountered several dozen feeding in a limited area, we were treated to really excellent views. The Monteiro’s showed us a great variety of different postures, but there was relatively little of the surface pattering typically seen when Wilson’s and British Storm Petrels are feeding, the Monteiro’s preferring to dip only for very brief moments. A tail fork was visible on almost every bird, though not in every posture or from every angle.

Before the existence of cryptic storm petrel species came to light, Michael O’Brien reported seeing hundreds of band-rumped storm petrels in the Gulf Stream, off the Atlantic coast of the USA, none of which had a discernible tail fork (Sangster 1999). While moult could temporarily alter or distort tail shape, one would hardly expect it to affect every single bird. The time of year when band-rumped are seen there, May until September, coincides with hot-season breeding, so most individuals in the Western Atlantic, many of which are in active primary moult, are probably post-breeders from a cool-season population. The main candidate for Gulf Stream birds is the geographically closer Grant’s Storm Petrel, but Cape Verde Storm Petrel is also partly a cool-season breeder. At the moment we can only guess how to distinguish between Grant’s and Cape Verde at sea. Monteiro’s Storm Petrels have longer tails with a fork averaging more than twice as deep as in Grant’s, although this fork is not in itself a diagnostic field mark, due to overlap in measurements (Mark Bolton in litt). Most Monteiro’s should have been in the Azores at the time of year when O’Brien was out in the Gulf Stream.

As we watched Monteiro’s Storm Petrel at sea off Graciosa, we noticed some subtle plumage patterns. In particular, many Monteiro’s seemed to have a more prominent diagonal wing bar than the presumed Madeiran Storm Petrels we had seen on the way to the Selvagens in June 2006. Instead of petering out long before reaching the carpal joint, at sea Monteiro’s’ wing bar looks prominent most of the way across, albeit more concentrated close to the body. We also felt that the white upper tail covert band was more prominent in Monteiro’s than in Madeiran. However, when Verónica started taking measurements, it soon became clear that the band’s width could vary enormously, with some birds having a band twice as wide as others. As far as we are aware, the corresponding ‘bandwidth’ of Grant’s and Madeiran has not yet been measured.

While Killian was lining up an approaching Monteiro’s Storm Petrel, a Black-capped Petrel Pterodroma hasitata shot through his view finder, only to disappear instantly, like an apparition. After a few moments of semi-disbelief, we relocated it rising up out of the wave troughs, coming back to inspect us. It is hard to think of a more exciting rare seabird in the eastern Atlantic. We were ecstatic, well aware that this species had only been seen alive once or twice in the entire Western Palearctic, and had never been photographed. Killian fired off a series of record shots while I admired the deep bill, unmistakeable underwing pattern, and the white neck and uppertail coverts. No bird I have ever seen gave me such an adrenaline kick, and it lasted for a long, long time.

Black-capped Petrel Pterodroma hasitata, south-east of Graciosa, Azores, 26 May 2007 (Killian Mullarney). This was the first for the Azores.

Black-capped Petrel is rare, and not just in the Western Palearctic. The world population, breeding in the Caribbean, is thought to be in the region of 600 to 2000 pairs (Lee 2000), and BirdLife International classifies it as ‘endangered’. But Monteiro’s Storm Petrel is actually much rarer. The three colonies off Graciosa, on Baixo, Baleia and Praia islets, are thought to hold about 230-250 pairs between them, and a further 50 or so are suspected of breeding on islets off Corvo and Flores, the westernmost islands of the Azores (Monteiro et al 1999).

During our last night on Praia, shortly after recording CD2- 47, I heard a storm petrel that sounded different from all the Monteiro’s Storm Petrels around it. I recognised it immediately, as I had heard hundreds a year previously, and first recorded its chatter calls back in August 2001. While preparing this book, I had listened to those recordings many times. The bird in question was a Madeiran Storm Petrel, the hot-season bird that replaces Monteiro’s from the Madeiran archipelago to the Canary Islands. It had never before been recorded in the Azores. My microphones captured four of its chatter calls as it flew along the cliff. The fact that it stood out among the Monteiro’s of Praia islet was a nice case of ‘the exception proves the rule’.