Killian Mullarney

Arnoud’s heart sank. Had he and René really come all the way to Marettimo to record Mediterranean Storm Petrels H melitensis, only to be told that their breeding cave was impossible to reach? None of the fishermen wanted to risk their boat by moving in close to the cave. They were full of admiration for the clever little storm petrels, nesting where no right-minded human being or other mammal would dream of disturbing them.

And yet ringers had somehow been visiting the cave for years. This was why Sicilian birder Andrea Corso had recommended it. Marettimo is the westernmost of the Egadi islands, just beyond Sicily’s western end. Andrea had put Arnoud and René in touch with Renzo Ientile and Nino Di Lucia, who make a ringing expedition for migrant passerines to the small but high, rocky and beautifully vegetated island for several weeks every spring. Renzo’s storm petrel ringing expedition takes place later in the year when the sea temperature is high enough for a long swim into the pitch dark cave, with a torch strapped onto his head. He also carries a spare torch since, without a light, it is considered almost impossible to find a way out of the cave. Andrea must have said kind things about the visitors from the north, because they were given the best beds in the house, and soon the red wine was flowing. Such a warm welcome was wonderful, but not exactly the night entertainment Arnoud and René had in mind.

The next morning, after enlisting the help of Vito, the island’s ‘mayor’, a fisherman called Giovanni was persuaded to take them to see the cave by daylight, to find out if it was really all that bad. Much to Arnoud’s relief, the sea was calm, and as they sailed north from the small fishing port, the island’s pine woods and spring colours were a beautiful sight. Although Arnoud and René could understand very little Italian, Giovanni was full of stories, including one that somehow linked Homer’s Odyssey with the origin of the word ‘procellaria’ (petrels). After they passed Punta Troia, a cape with a Norman tower on top, the scenery became more jagged and rocky, with hardly any signs of humanity. On the western side of the island there were quite a few caves of different sizes. When they had been at sea for an hour or so, Giovanni pointed the boat towards the highest and steepest cliff, which dwarfed a tiny grotto, way down at the bottom.

Marettimo, Egadi islands, Sicily, 17 April 2007 (René Pop). The cave where CD2-22 to CD2-26 were recorded.

As they sailed closer, a petrel scent wafting towards them confirmed that this was the right cave, but there was nowhere for them to land. It soon became clear why the ringers always entered by swimming. When Giovanni sailed close enough that the boat was actually inside the entrance to the cave, Arnoud noticed a rock on the right that he was able to jump onto. Using all four limbs, he climbed up to a tiny, table-sized plateau. Giovanni was horrified, and called him back, but Arnoud carried on. Tracking the strongest petrel scent behind a large rock, he sniffed his way through a large crevice and into complete darkness. When he switched on his torch, it looked like the inside of a giant’s brain. The rocks had a texture like cerebral cortex, although they were deceptively hard. Around the edge of the chamber, several storm petrels were sitting around in pairs under slimy-looking stalactites of various colours. He slipped back out and called René up to join him.

For the next hour, they listened to the peculiar sound of Mediterranean Storm Petrels calling in total darkness, right in the middle of the day. Despite being paired, these storm petrels were not calling from spots in the cave where you would expect them to lay an egg. The calling never really became intense, although it included quite a variety of calls. Listen to the petrels calling, as the sea echoes throughout the cave (CD2-22).

CD2-22: Mediterranean Storm Petrel Hydrobates melitensis Marettimo, Egadi islands, Sicily, 12:01, 17 April 2007. Various calls of presumed pairs in a completely dark cave at midday. These include chatter calls, aborted bouts of purring, and a wheezing sound resembling the breath note in purring calls. 07.015.AB.01526.11

Since there was a chance that they might not be able to return, Arnoud recorded as much as he could. Eventually, the sound of Giovanni’s motor could be heard again, and it was time to leave. The boatman made it quite clear that there was no question of attempting to land them in the cave in the dark. Too risky for his boat, an important part of his livelihood, and besides, a sirocco all the way from the Sahara could blow up at any time, stranding them in the cave for days on end. But the weather was calm, excellent even, so Arnoud and René made some more enquiries. Eventually, a fisherman called Leonardo was found, who was willing to bring them at night for a somewhat inflated fee, but not until the next night.

Leonardo was not afraid of the cave, and he happened to own the smallest boat in the harbour, ideal for getting close to the rocks. When they got to Punta Troia, they would assess the strength of the wind coming from the south-west. Arnoud and René crowded into the tiny boat, and they left the harbour behind them. Rounding the cape, the wind was not too bad, so they continued to the cave, arriving at dusk. Leonardo retreated to a distance where his motor could not be heard, having arranged to pick them up a couple of hours later.

Soon it was totally dark, both inside and outside the cave. Just a day after new moon, there was a high level of activity among the storm petrels. In a constant stream, they were arriving, then disappearing into the recesses of the 200 m deep cave. Many also flew into the chamber Arnoud had discovered in the daytime. It turned out that there was a small, football-sized hole at the back, which the storm petrels were piling into. When Arnoud went there to listen, he heard a chorus of males purring away in an inaccessible chamber, somewhere down below. You really must listen to CD2-23 through headphones, to experience the sea pushing in through the cave entrance while birds arrive and clamber past Arnoud and his microphones, with others calling from all sides.

CD2-23: Mediterranean Storm Petrel Hydrobates melitensis Marettimo, Egadi islands, Sicily, 20:56, 18 April 2007. Chatter calls, wingbeats and a chorus of purring males, recorded at a small hole, leading to an inaccessible part of the cave. 07.016.AB.02251.20

On reflection, it seems quite amazing that the storm petrels are able to make their way into the cave in total darkness, avoid the stalactites, and find a hole the size of a football, leading to another chamber. How do they do it? Ranft & Slater (1987) investigated the possibility that British Storm Petrels might echolocate with very high frequencies, like bats or dolphins. However, when they took their ultrasound receivers along to colonies on Skokholm, Wales, and Mousa, Shetland, they were unable to detect any ultrasonic calls. Might storm petrels do the same as several species of swiftlets Apodidae, which use audible calls, below the ultrasonic range, for echolocation? European storm petrels give rather few calls in flight, however, so this is probably not how they find their way in the dark.

Mediterranean Storm Petrels Hydrobates melitensis, Marettimo, Egadi islands, Sicily, 17 April 2007 (René Pop). Inside cave at noon.

Another possibility is that storm petrels use their sense of smell to locate their nests, just like Arnoud had done. An experiment with Mediterranean Storm Petrels in Spain gives strong support for this idea. De León et al (2003) tested the ability of storm petrel nestlings to identify their own scent, using a T-shaped tunnel. The nestlings could enter the tunnel at the ‘foot’ of the T, and scents could be placed at the two extremities of the T’s crossbar. When the nestlings came to the T-junction, most of them went in the direction where their own scent had been impregnated, proving they were capable of distinguishing their own from the scent of another nestling. Under natural conditions, this would enable them to relocate their own nest in a dense network of crevices. It seems reasonable to assume that adults can do this too.

Arnoud and René’s visit to Marettimo took place early in the breeding season, around the time when the very first eggs are laid (Mínguez 1994), so most of the Mediterranean Storm Petrels visiting the cave would have been breeders. Almost all of the calls recorded came from birds sitting on the cave floor, or hidden away in crevices. Only one bird was heard calling in flight, a series of wick-wick-wick calls very similar to those of British Storm Petrel. The time for hearing chatter calls and purring in flight may be later in the season, when the majority of non-breeders arrive.

Mediterranean Storm Petrel Hydrobates melitensis, large nestling, Cabrera, Balearic Islands, 10 August 2005 (Miguel McMinn)

Chatter calls of Mediterranean Storm Petrel differ markedly from those of British Storm Petrel. As in British, they typically have three parts, with the longest note in the middle. The most typical variant can be transcribed as Do-errr-chik. Perhaps the most striking characteristic of Mediterranean chatter calls is the way that the notes tend to be slurred together. A short, sharply articulated note at the start is slurred to a longer, weakly articulated note in the middle. There is always a short gap, however, before the chik note at the end. A typical example of a Mediterranean chatter call can be heard at 0:01 in CD2-24. Compared to British, the first note is more prominent and there is not nearly so much accent on the longer syllable in the middle. In addition, chatter calls of Mediterranean are somewhat shorter.

CD2-24: Mediterranean Storm Petrel Hydrobates melitensis Marettimo, Egadi islands, Sicily, 21:07, 18 April 2007. Several individuals chatter calling and purring. The one giving the typical chatter call at 0:01 later turns out to be a male, when it starts purring at 0:29. 07.014.AB.01505b.11

Mediterranean Storm Petrels Hydrobates melitensis, Marettimo, Egadi islands, Sicily, 18 April 2007 (Arnoud B van den Berg). Piling into small hole at back of chamber in cave at night.

A number of variations can be heard in Mediterranean Storm Petrel chatter calls, none of which overlap with British Storm Petrel. For example, Mediterranean sometimes doubles the chik note, which I have never heard in British, despite listening to hundreds of individuals. This can be heard in the second and third calls of CD2-25, and at various points later in the same track. In the same recording, you can also hear chatter calls with more than one short note slurred together at the start. British never seems to have more than one clearly articulated short note at the start, and sometimes it has none at all.

CD2-25: Mediterranean Storm Petrel Hydrobates melitensis Marettimo, Egadi islands, Sicily, 21:07, 18 April 2007. Chatter calls and purring of several individuals, most of which are males. Some chatter calls, eg, the second and third in the recording, have a double chik note at the end. These are given by a bird of unknown sex. 07.014.AB.01505a.11

Chatter calls lacking the final chik note are particularly prominent in CD2-26, where you can hear a long series of them. It seems likely that variations in chatter calls are required for individual recognition. A similar degree of variability can be heard in calls of Manx Shearwater Puffinus puffinus, where this is known to be important. Other storm petrels, such as Cape Verde Storm Petrel O jabejabe, also have quite variable chatter calls, although the variability seems to be less noticeable when the call contains a larger number of notes.

CD2-26: Mediterranean Storm Petrel Hydrobates melitensis Marettimo, Egadi islands, Sicily, 21:07, 18 April 2007. A long series of chatter calls of a male, often with several notes slurred together at the start, and lacking the final chik note. 07.014.AB.01505c.11

It was a relief for me to hear Arnoud’s recordings from Marettimo, because they confirmed the strong impression I had when I first heard Mediterranean Storm Petrels on Benidorm island in Spain. In The Sound Approach to birding (2006), we boldly stated that chatter calls of British and Mediterranean Storm Petrels differed, although at the time this was based on a sample of just a few Spanish individuals. Arnoud’s recordings were made in April, but my visit to Benidorm island took place in early August, a time when piercing begging calls of nestlings dominated the sound of the colony. Thanks to Arnoud’s recordings I now know that Mediterranean has the same diagnostic calls not only in two colonies 1065 km apart, but also at opposite ends of the breeding season. Listen to chatter calls from Benidorm (CD2- 27), and see if you agree that these birds sound far more like the other melitensis from Marettimo (eg, CD2-24) than to pelagicus from the Atlantic (eg, CD2-16).

CD2-27: Mediterranean Storm Petrel Hydrobates melitensis Benidorm island, Alicante, Spain, 7 August 2002. Chatter calls and purring of adults, with high-pitched rhythmic and long begging calls of well developed nestlings in the background. 02.038.MR.03333b.00

CD2-24: Mediterranean Storm Petrel Hydrobates melitensis Marettimo, Egadi islands, Sicily, 21:07, 18 April 2007. Several individuals chatter calling and purring. The one giving the typical chatter call at 0:01 later turns out to be a male, when it starts purring at 0:29. 07.014.AB.01505b.11

CD2-16: British Storm Petrel Hydrobates pelagicus Skellig Michael, Kerry, Ireland, 00:13, 26 August 2006. A male on the left gives chatter calls and snatches of purring song, while a possible female on the right responds with chatter calls. 060826.MR.01357.00

I must admit that when I first heard purring calls of Mediterranean Storm Petrel on Benidorm island, they did not strike me as very different from British Storm Petrel. Later however, with more experience and a much larger sample of recordings to listen to, I noticed that Mediterranean has higher pitched breath notes. To verify this, I compared purring of 11 British from Mousa and Skellig Michael with 12 Mediterraneans from both Benidorm and Marettimo. The maximum frequency of the breath note averaged 426 Hz in British, but 637 Hz in Mediterranean, which is 50% higher. Only one British had breath notes above 500 Hz, and only one Mediterranean had breath notes below this. To hear the difference for yourself, listen to the high-pitched breath notes in CD2-28, then compare them with the British in CD2-18 and CD2-19.

CD2-28: Mediterranean Storm Petrel Hydrobates melitensis Benidorm island, Alicante, Spain, 7 August 2002. Purring calls, with higher pitched breath notes than British Storm Petrel. Background: calls of nestlings. 02.038.MR.03140.00

CD2-18: British Storm Petrel Hydrobates pelagicus Skellig Michael, Kerry, Ireland, 02:35, 27 August 2006. Purring song of up to seven males, in a high wall just beside the entrance to Skellig Michael’s 7th century monastery. Background: rhythmic begging calls of nestlings. 060827.MR.23503.01

CD2-19: British Storm Petrel Hydrobates pelagicus Mousa, Shetland, Scotland, 23:18, 11 July 2001. Purring song of several males, in the walls of an Iron Age fort. 01.032.MR.11706.00

As far as I am aware, only one author, Vincent Bretagnolle, has compared British and Mediterranean Storm Petrel calls before. However, Bretagnolle only published statistics about the degree of difference, and no information about the nature of these differences. Bretagnolle did include the results of some interesting playback tests. Both British and Mediterranean showed significantly higher response rates to purring calls of their own taxon (Bretagnolle 1998). This is important, because purring is used by males to attract a mate. A lack of interest in each other’s purring calls could well prevent interbreeding, should British and Mediterranean ever occur in the same colony.

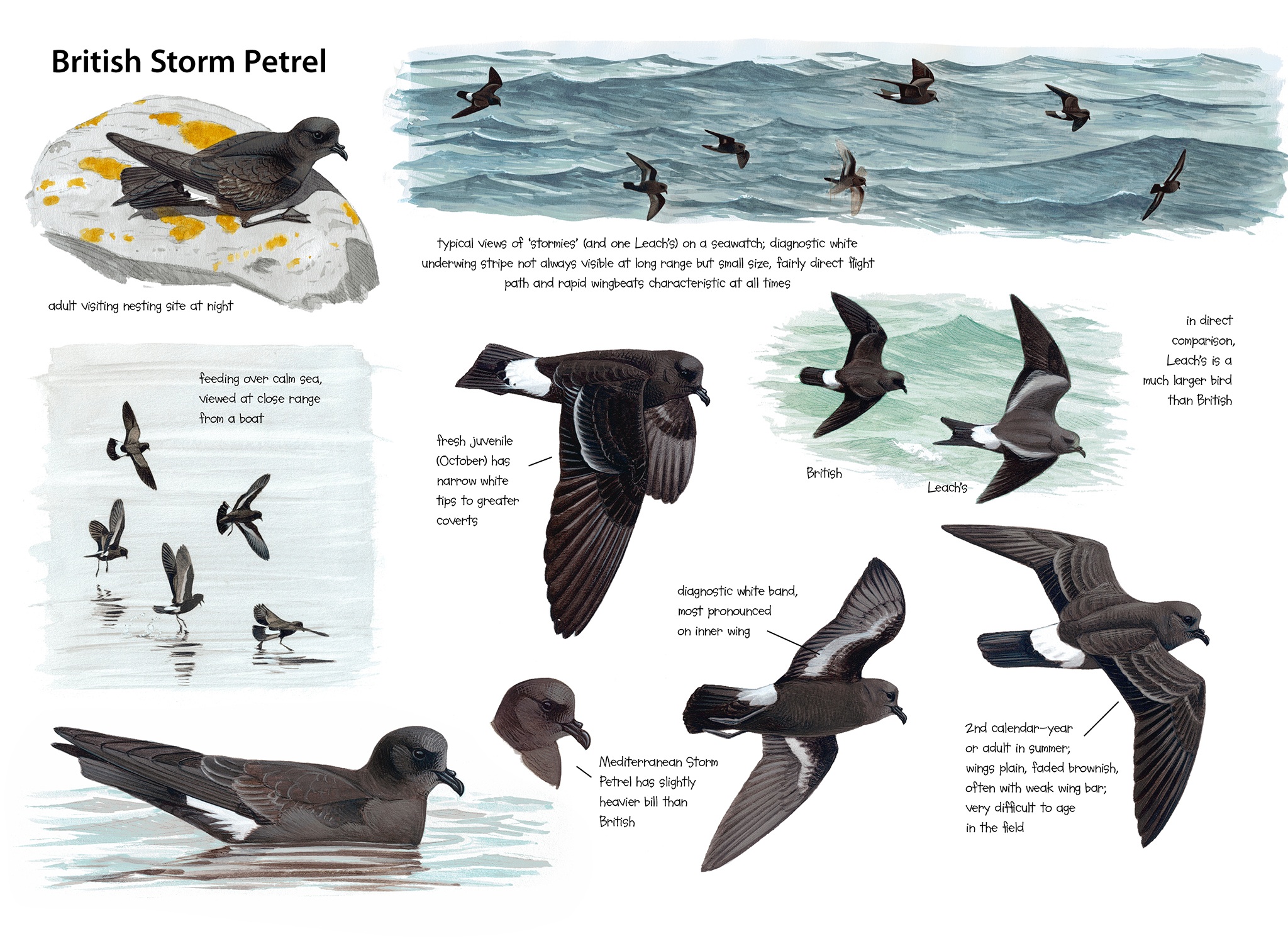

What other differences are there between British and Mediterranean Storm Petrels, besides these vocal ones? At present, no field characters are known that can be used to separate them easily at sea. However, when Killian saw photographs that Arnoud and René brought back from the cave on Marettimo, he was immediately struck by the heavy bill. Killian was unaware that, more than 20 years ago, French and Italian ornithologists published papers showing that Mediterranean is a slightly larger bird, and that a more voluminous bill is the best way to separate them from their Atlantic counterparts, at least in the hand (Hémery & Elbée 1985, Massa & Catalisano 1986a, 1986b).

Mediterranean Storm Petrel Hydrobates melitensis, Marettimo, Egadi islands, Sicily, 18 April 2007 (René Pop). Inside cave at night.

Mediterranean Storm Petrel Hydrobates melitensis, Marettimo, Egadi islands, Sicily, 18 April 2007 (René Pop). Inside cave at night.

Killian also noted that most of the storm petrels in the photographs showed a very uniform, blackish wing, lacking the somewhat browner coverts and more or less prominent narrow wing bar usually shown by British, formed by pale tips to the greater coverts. Photographs taken by René on Skomer on 8 June, a similar point in the moult cycle of British, show much more contrast in the wing. Melitensis was originally described by Antonio Schembri (1843) on the basis of differences in colour. But these were later dismissed as erroneous, explained merely by fresh and worn plumage (Mayaud 1941, 1949). Perhaps now it is time for a critical reappraisal of potential differences in colour.

Because Mediterranean Storm Petrels breed about a month earlier than their Atlantic counterparts, they follow an earlier moult schedule. Primary moult starts on average as early as 25 June on Benidorm, where most juveniles fledge in August, but 22 July in a colony of British Storm Petrels on the Atlantic coast of Spain, where fledging occurs in early September (Arroyo et al 2004). In southern Wales, primary moult starts on average a month later still, and most juveniles fledge in October (Scott 1970). A bird I photographed in the hand in the Balearic Islands in late July was well into its primary moult, which is normal for Mediterranean at this time, but would be uncommon in a colony of British. Because immatures, non-breeders and failed breeders moult earlier than breeders, however, moult is a tricky character to use in the field.

Mediterranean Storm Petrel Hydrobates melitensis, Marettimo, Egadi islands, Sicily, 18 April 2007 (René Pop). Inside cave at night.

British Storm Petrels breed later than Mediterranean Storm Petrels, even as far south as the Canary Islands, where laying takes place in late June and July (Nogales et al 1993), a schedule similar to colonies in the British Isles. Moreno (2000) included two recordings of purring in his CDs of Canary Islands bird sounds, allowing me to check whether they were pelagicus or melitensis. Because the lowest frequencies had been filtered away, I had to deduce the fundamental frequency of the breath notes from their harmonics. The maximum averaged 370 Hz in one bird and 430 Hz in the other, which means that their purring is not dissimilar to that of other Atlantic populations. Moreno’s description of chatter calls – ap-cheer-chip – suggests to me that the accent is on the second note, which also fits better with British, rather than Mediterranean.

If genes were something you could see or hear in the field, then identifying a Mediterranean Storm Petrel would be a rather straightforward matter. Cagnon et al (2004) studied the mtDNA of 65 British and Mediterranean Storm Petrels from five different localities, which did not include the Canary Islands. Two different methods were applied, and both came up with the same result. Atlantic and Mediterranean populations represent two well differentiated lineages and there is no evidence of gene flow between them. The time when these two lineages diverged was estimated at 550 000 years ago, but Cagnon et al were rather timid when it came to the taxonomic implications of their work. Without explaining why, they used their results to justify maintaining two ‘subspecies’. Personally, I would draw a different conclusion, based not only on their DNA work, but also the vocal differences I have detected, Hémery & Elbée’s work on bill sizes, and Bretagnolle’s playback tests: British and Mediterranean Storm Petrels are best treated as separate but closely related cryptic species.

To seabird enthusiasts in northern Europe, identification of Mediterranean Storm Petrel might seem like a rather abstract and meaningless challenge. After all, you just need to know where, geographically, you are seawatching and the problem is solved! Until recently, there was no evidence of Mediterraneans leaving the confines of their own sea. Could the geography of storm petrels really be that simple? A storm petrel found dead on a North Sea beach on 15 September 1989 suggests otherwise. The bird, which was found on Ameland, one of the Frisian islands strung along the northern coast of the Netherlands, had been ringed on 10 July 1971 in a colony in Malta. Although it was reported to the Dutch ringing centre at the time, this record only came to light after the news was published in a Maltese ringing report 16 years later (Il Merill 31: 39, 2005). So far, efforts to find out more about this potential first for the Netherlands have proved fruitless, and the specimen appears not to have been preserved. Further digging in the Maltese ringing annals revealed that another Mediterranean Storm Petrel was recovered on the Atlantic coast of France. Ringed on Malta on 24 May 1986, it was found on the Côte Sauvage, La Tremblade, Charente-Maritime, on 2 February 1990 (Il Merill 28: 71, 1995). Unfortunately, neither of these storm petrels was ringed as a nestling, so in theory they could have been Atlantic vagrants visiting a Maltese colony when they were trapped.

Observations in the Strait of Gibraltar suggest that the number of Mediterranean Storm Petrels venturing into the Atlantic cannot be very high. After sailing 407 transects between Algeciras in Europe and Ceuta in North Africa from August to December, Hashmi & Fliege (1994) estimated that only 1100- 1700 storm petrels left the Mediterranean during the period of their research. Surprisingly, however, an estimated 6300-9500 entered the Mediterranean during the same period. Most arrived during October and November, roughly the period when British Storm Petrels from further north are starting to migrate south. Some if not most of the departing storm petrels may have been Atlantic birds too, having entered the Mediterranean and found it not to their liking.

Definite proof that Mediterranean Storm Petrels occur in the Atlantic only came while I was writing this book. Reading a weblog about ringing migrating storm petrels in the Algarve, Portugal (stormies-online.blogspot.com), I learned that an Italian-ringed bird had been trapped there on the night of 26/27 May 2007. I wrote to Rob Thomas, leader of the ringing group, to tell him about the Dutch and French recoveries, then put him in touch with Renzo Ientile, our friend from Marettimo. Sure enough, the bird had been ringed on 16 July 2004 in the very cave visited by Arnoud and René. The fact that it was ringed as a nestling confirmed that it was Italian by birth, and therefore the first indisputable record of melitensis for Portugal and the Atlantic Ocean.

European storm petrels: known breeding distribution.

Recording locations indicated by arrows (red dots).

British Storm Petrel Hydrobates pelagicus.

Recordings (north to south): Elliðaey, Vestmannaeyjar, Iceland; Mousa, Shetland, Scotland; Carnsore Point, Wexford, Ireland; Skellig Michael, Kerry, Ireland.

Mediterranean Storm Petrel Hydrobates melitensis (blue dots).

Recordings (west to east): Benidorm island, Alicante, Spain; Marettimo, Egadi islands, Sicily.

Mediterranean Storm Petrel is not a common bird. There are only thought to be around 20 000 pairs (Hernández Gil 1997), with the largest colonies in the Balearic Islands, on Fiflia, Malta, and on Marettimo (Massa & Sultana 1990, Mínguez 2004). Meanwhile, British Storm Petrel is thought to number around half a million pairs, with the largest colonies in the Faeroes and south-western Ireland (Brooke 2004). Being 20-30 times more common, it is no great surprise that pelagicus outnumbers melitensis at the Strait of Gibraltar in autumn. With so many British able to find their way into the Mediterranean, it is all the more remarkable that gene flow between the two species is not taking place.

Mediterranean Storm Petrels are in need of protection, and I was encouraged to see that SEO/BirdLife Spain declared 2007 the ‘year of the storm petrel’. Eduardo Mínguez, the man who showed me around the colonies on Benidorm island, is the storm petrel’s best friend in Spain. He even speaks their language. Eduardo explained to me that one of the biggest problems facing these birds is light pollution from tourist developments, lighting up their breeding habitat in the dark and making them more vulnerable to predation. The cave where I made my recordings was a case in point, lit up by the promenade of Benidorm town. Yet colonies like the one on Marettimo give hope that there still may be sizeable populations waiting to be discovered, hidden away in little, dark grottos that nobody ever even noticed.

Benidorm island, Alicante, Spain, 7 August 2002 (Magnus Robb). The tourist hotels of Benidorm town on the mainland, seen from the cave where CD2-27 and CD2-28 were recorded.