In the opportunity of a lifetime, Magnus finally went to the island of Bugio near the Madeira archipelago to record Desertas Petrels Pterodroma deserta in 2011, several years after completing Petrels night and day. This recording probably includes a significant proportion of the world population of fewer than 200 pairs.

Magnus talks about his experience sound recording Desertas Petrel in Madeira

Killian Mullarney

Text by Magnus Robb.

Almost everything we know about the breeding biology of ‘Fea’s Petrel’ actually refers to Desertas Petrel, which breeds on the island of Bugio in the Desertas. In deserta, eggs are laid in July-August, about five months before feae, which lays in December and January in the Cape Verde Islands. These two populations are not only separated in time; their breeding colonies are 2000 km apart, so it seems most unlikely that interbreeding takes place. Desertas averages larger in several measurements, and its average bill depth is greater than Fea’s, almost to the same extent that Fea’s is greater than Zino’s Petrel (Bretagnolle 1995). It seems likely that Desertas and Fea’s have been reproductively isolated for some time. Indeed, Ratcliffe et al (2000) thought they were “probably cryptic species”. Results from two teams investigating DNA have yet to become known, but as we will see, differences in their sounds suggest that Desertas may actually be the most divergent member of the group.

Bugio is a long, narrow island, shaped for the most part like a jagged comb, but with plateaux at either end. There are no easy places to land, because its precipitous slopes plunge straight into the sea on all sides. When the north-east trade wind blows, and the waves are not too high, it is sometimes possible to land near the southern end of the island. The main Desertas Petrel colony is on the southern plateau, which is nowhere more than 50 m wide. The island is not only wild, inaccessible and treacherous to climb; it is also fiercely protected. While the world’s only breeding Desertas Petrels would easily justify strictly limited access, Bugio is also home to an extremely rare mammal. About 30

Bugio is a long, narrow island, shaped for the most part like a jagged comb, but with plateaux at either end. There are no easy places to land, because its precipitous slopes plunge straight into the sea on all sides. When the north-east trade wind blows, and the waves are not too high, it is sometimes possible to land near the southern end of the island. The main Desertas Petrel colony is on the southern plateau, which is nowhere more than 50 m wide. The island is not only wild, inaccessible and treacherous to climb; it is also fiercely protected. While the world’s only breeding Desertas Petrels would easily justify strictly limited access, Bugio is also home to an extremely rare mammal. About 30 of the world’s 600 or so Mediterranean Monk Seals Monachus monachus live in its sea caves. There is a marine exclusion zone around Bugio to give this shy species some peace and quiet. Wardens based on the neighbouring island of Deserta Grande will chase away anybody who has no business to be there.

The ship that was to take René Pop and me to Deserta Grande, from where we hoped to go to Bugio, was a 292 ton Portuguese navy patrol boat called the NRP Save, which relieves the wardens every two weeks. But we learned the evening before that we would be unable to land. Permission had been granted by the conservation authorities, but the weather gods were against us. A rare south-west wind was strengthening day by day, and it eventually reached force 10. Still, the navy allowed us to go along for the ride, on the understanding that we returned with the ship in the evening. In the freshening wind, the flight of the Desertas Petrels was fast and spectacular. They moved in great arcs, towering high above the waves, switching the angle of their wings with incredible speed, and hardly flapping at all. At the top of an arc, the wings were stretched briefly in the vertical position or beyond, and their black underwings took the full force of the wind. Then they would switch back and glide down into the next trough, showing the grey upperside of the wings before disappearing.

Could some of these petrels have been Zino’s Petrels? On 20 October 2006, numbers of Desertas Petrels were close to their peak. Not only would most breeding adults be present, but many young non-breeders would be around too. October tends to be the top month to see Desertas in good numbers, and strong winds show them at their best. Meanwhile, all the young Zino’s would have fledged, and the adults would have departed for their unknown wintering grounds. We saw about 50 gadfly petrels that day, presumably all Desertas. While this was exciting, and René got some nice photographs, it was little help to me or our sound project.

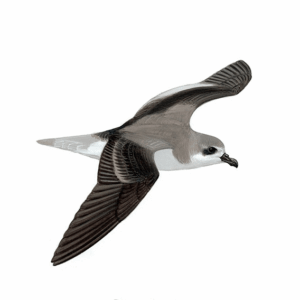

Desertas Petrel Pterodroma deserta, near the Desertas, with Porto Santo in the background, Madeira, 30 June 2006 (Killian Mullarney)

On returning to Madeira, I went to visit Frank and Buffy Zino at their home, and we talked about recordings of Desertas Petrels that had been made on Bugio in the past. These included the ones made 40 years ago by Alec Zino, which had played such a crucial role in the rediscovery of Zino’s Petrel. I was afraid to play the historic original tape for fear that it might disintegrate, so we agreed to have the tape sent to the USA to be professionally restored and copied. The cost turned out to be seven bottles of Van Wees cinnamon liqueur, because the restorer’s favourite tipple is distilled close to my home in Amsterdam!

Desertas Petrel Pterodroma deserta, near the Desertas, Madeira, 30 June 2006 (Killian Mullarney)

The Desertas Petrels you can hear in CD1-10 were recorded during the night of 28/29 September 1967. The birds arrived towards 20:00, calling beautifully, and fell silent by about midnight. A waning crescent moon rose just before 03:00, and sometime afterwards Alec was able to observe the pre-dawn exodus (Jouanin et al 1969). The beating of wings was perfectly audible, but the petrels departed without a single call. At this stage in the breeding cycle, the earliest nestlings would be a few days old, and indeed one was seen in a burrow that night. Most of the birds calling would have been non-breeders, performing their courtship display flights in preparation for future breeding attempts. Most of these calls are moans, clearly equivalent to the moans of Fea’s and Zino’s Petrels. Some of the shorter, single-note calls sound a bit like whimpering, because they rise so sharply in pitch. Examples can be heard at 0:27 and 0:36. A proper three-note Desertas Petrel whimpering call can be heard in the distance at 0:53. However, the whimperings in Alec’s recordings of Desertas are never as fully developed as in my own recordings of Zino’s.

CD1-10 Desertas Petrel Pterodroma deserta, Bugio, Desertas, Madeira, 28 September 1967. Moaning calls, the majority of which are of the low type. A distant whimpering call can be heard at 0:53. Background: Cory’s Shearwater Calonectris borealis and Grant’s Storm Petrel. Paul Alexander Zino.

CD1-06: Fea’s Petrel Pterodroma feae Chã Dura, Santo Antão, Cape Verde Islands, 20:25, 18 February 2007. Moaning calls of a presumed courting pair in spectacular nocturnal display flights, using the entire airspace of a precipitous gorge. 070218.MR.202509b.01

In fact, a rise in pitch at the end of a call is a strong characteristic of most Desertas Petrel calls. More than 75% of their moans, both high and low variants, end with a rapidly rising squeak, which typically sounds like -wik. Sometimes this inflection is less obvious, for example when the call has been recorded from a distance. In the sonagram taken from the start of CD1-10, you can see it as the slight upward flick at the end of each call. There is also a very high pitched component, too high to show in these sonagrams. In Fea’s and Zino’s Petrels, only a minority of moans have –wik endings, although both of the high calls in the sonagram from CD1-06 do have them.

Another key difference I noticed when comparing with Fea’s or Zino’s Petrels was that moans of Desertas Petrel drop less in pitch over the main part of the call, as you can see more clearly in the zoomed-in sonagram taken from the start of CD1-11. Compare it to the zoomed-in sonagrams of the other two gadfly petrels: in Fea’s and Zino’s the descent is steeper and more curving.

CD1-11 Desertas Petrel Pterodroma deserta, Bugio, Desertas, Madeira, 28 September 1967. Moaning calls, with a distant whimpering call at 0:31. Background: Cory’s Shearwater Calonectris borealis and Grant’s Storm Petrel. Paul Alexander Zino.

To find out whether these differences were genuine, I analysed sonagrams of 312 calls of Desertas, Fea’s and Zino’s Petrels, both high type and low type moans. The much higher proportion of –wik endings and the smaller drop in pitch over the main part of the call in Desertas were confirmed. I also noticed that high and low moans of Desertas differ more from each other in fundamental frequency. Curiously, all three characteristics bring it a little closer to Cahow. Moans of this western Atlantic petrel are always inflected at the end, descend only slightly in pitch and, judging by ear, there is an even greater difference between high type and low type calls than in Desertas. Recordings of the Cahow can be listened to online, at www.animalbehavior.org, the website of the Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York, USA.

Desertas Petrel Pterodroma deserta, near the Desertas, Madeira, 30 June 2006 (Killian Mullarney)

If Cahow, Black-capped or another West Atlantic petrel was the ancestor of the Macaronesian gadfly petrels, as has often been suggested, then the Azores were probably the first archipelago to be colonised. Killian and I saw a Black-capped Petrel there in May 2007, and a vagrant Cahow was recently discovered prospecting in a petrel colony in the east of the archipelago. It was first trapped and photographed on 17 November 2002 (Bried & Magalhães 2004), and has subsequently been observed on the same islet in 2003 and December 2006. Cahow was thought to be extinct for 300 years, until a colony was rediscovered on an islet off Bermuda, in 1951 (Murphy & Mowbray 1951). Since then, the tiny Bermuda population has been tended with loving care, but there were still only 72 breeding pairs in 2005 (www.birdlife.org), making the record from the Azores all the more remarkable.

With all this in mind, it is perhaps less surprising that the Azores may be home to a tiny population of Desertas Petrels. Gadfly petrels trapped here in 1990, 1993 and 1994 had measurements at the upper end of the range for deserta (Monteiro & Furness 1995). Two were also heard and one of them was trapped in August 1999. Whether these were prospecting breeders originating from Bugio or relicts of a once larger Azores population is a matter of guesswork, but there are hints that a gadfly petrel may have been commoner here in the past. A bird called the ‘boeiro’ is mentioned in historical chronicles from the 16th and 17th centuries. Said to have been a burrowing seabird the size of a Manx Shearwater Puffinus puffinus, it was harvested mainly from October to December, ie, the chick rearing period of Desertas, on the western islands of Corvo and Flores (Monteiro et al 1996a).

Desertas Petrel Pterodroma deserta, near the Desertas, Madeira, 30 June 2006 (Killian Mullarney)

Gadfly petrels certainly had a much wider distribution in the north-eastern Atlantic in the past. Harald Pieper has found bones of Desertas Petrel on Deserta Grande, Madeira itself, and its north-eastern outlier Porto Santo, where a specimen was collected in July 1889 (Zino & Zino 1986). Pieper found no Pterodroma remains in a small sample of petrel bones from Selvagem Grande, Selvagens, 230 km south of Madeira. However, during the nights of 19 and 20 June 1983, ‘soft-plumaged petrel’ calls were heard there by two observers who were on the island to record and study petrel voices (James & Robertson 1985b). It is a shame they made no sound recordings of the calls they heard. Despite the regular presence of observers familiar with the voices of Desertas and Zino’s Petrels, no Pterodroma has been heard there since.

Curiously, there is only one record of a calling gadfly petrel from the Canary Islands, between Madeira and the Cape Verde Islands, despite plenty of apparently suitable breeding habitat. One was heard calling on three occasions in the Barranco del Agua, La Palma, in June 1998 (Martin & Lorenzo 2001). However, the westernmost island of the Canary Islands, El Hierro, once had a Pterodroma of its own (Rando 2002). Bones have been discovered in the Cueva de El Curascán in the north-east of the island, about 300 m above sea level. Several well-preserved skeletons were slightly larger in all measurements compared to Desertas Petrel. So far, they have not been dated more precisely than the cave itself, which is up to 50 000 years old. Atlantic trade winds were much stronger during the Pleistocene than during warmer periods such as the present. Together with cooler sea temperatures, this would have produced stronger upwellings, and a greater abundance of marine life, able to sustain a larger species of gadfly petrel. When the seas warmed and winds dropped at the end of the Pleistocene, the large El Hierro petrel may have gone into terminal decline.

Perhaps the biggest surprise concerning the past distribution of North Atlantic petrels is the recent discovery of Pterodroma remains in northern Europe. Finds are known from both sides of the Kattegat, separating Denmark and Sweden, and from a Roman settlement at Valkenburg, Zuid-Holland, the Netherlands (Leopold 2005). In Scotland, bones of Desertas/Fea’s Petrel have been found on North Uist and Islay, Western Isles, and on Rousay, Orkney (Serjeantson 2005). These were discovered in middens at archaeological sites dating from the first millennium AD. It is hard to conceive how gadfly petrels could have been trapped for human consumption, other than at breeding colonies in the vicinity. Climate change is not just a recent phenomenon, and perhaps the Scottish seas were more suitable for gadfly petrels in the past, before some change took place about 1000 years ago. Perhaps my ancestors were directly responsible for their decline, taking a ‘case e ase’ attitude, like the Cape Verde islanders of our own time.

Desertas Petrel Pterodroma deserta and its breeding island Bugio, Desertas, Madeira, 4 July 2005 (Filipe Viveiros)

2006 was the year that Fea’s Petrel was officially added to the contemporary British list, based on some excellent photographs of birds encountered near the Scillies in July and August 2001 (Fisher & Flood 2006, Lees 2006). In the same issue of British Birds, a paper by the rarities committee entitled “Do we know what British ‘soft-plumaged petrels’ are?” (Steele 2006), quietly swept the problem of Desertas Petrel versus Fea’s under the carpet. The answer to this question has to be: “no we don’t”, because at the present time nothing is known for certain about the respective movements of these two petrels away from their breeding grounds. Frank Zino has bought transmitters to fit onto Desertas from Bugio and follow their migration, but we may have to wait a year or two for the results.

Given that Desertas Petrel nests on Bugio in late summer, we can make an educated guess that British and Irish ‘Fea’s’ seen at that time are indeed feae, belonging to the Cape Verde population, which are off duty until late autumn. Fea’s Petrel is the more numerous of the two, with a breeding population estimated at about 500 to 1000 pairs (Ratcliffe et al 2000). Desertas numbers in the region of 170-260 pairs (BirdLife International 2004), making it only about two or three times less rare than Zino’s Petrel. The time has come for Desertas to be treated as a species in its own right, given that it differs from Fea’s Petrel in breeding phenology, size and sounds. It certainly deserves the strictest protection, and a search for new colonies is worth considering for anyone planning an autumn trip to the Azores.