Migrants in strange places

By Magnus Robb (with Nick Hopper and Paul Morton)

The ancient São Domingos mine complex in south-eastern Portugal, close to the border with Spain and some 52 km from the Algarve coast, is home to various rock and crevice-loving species of birds. Picture old mineshafts, buildings on the point of collapse and pools of very dodgy looking fluids. From White-rumped Swifts Apus caffer to a Eurasian Eagle Owl Bubo bubo that claimed a songpost where I had been hoping for a Western Black-eared Wheatear Oenanthe hispanica at dawn, I have had some great experiences at these mines. All with a smell of sulphur dioxide in the air and a mild sense of danger.

One night when I was trying to record Common Barn Owls Tyto alba breeding in the old mineheads I heard some strange whistling sounds approaching. At first I had no idea what I was hearing, except that this was clearly a flock. The sound made me think of ducks or waders. The whistles were slightly descending, about a tenth of a second long, and towards the upper range of what I can whistle with my lips. I was leaning towards some kind of duck, several of which have whistling calls, and then when the flock was right overhead I finally remembered where I had heard them before: Mývatn lake in northern Iceland. These were Common Scoters Melanitta nigra taking a short cut across the Iberian interior. I found this very surprising.

Common Scoter Melanitta nigra, Mina de São Domingos, Mértola, Portugal, 22:03, 12 March 2012 (Magnus Robb). A flock migrating overland, with only male calls audible. Background: Eurasian Eagle Owl Bubo bubo and distant village dogs.

Common Scoter Melanitta nigra, Mina de São Domingos, Mértola, Portugal, 22:03, 12 March 2012 (Magnus Robb). A flock migrating overland, with only male calls audible. Background: Eurasian Eagle Owl Bubo bubo and distant village dogs. 120312.MR.220305.11

Three years later I was in the same area just one day earlier in the calendar when I heard Common Scoters again. I was staying the night at a steppe reserve called Vale Gonçalinho, and my microphones were set up for a pair of Little Owls Athene vidalii. This time there were only four whistles, and had it not been for my previous experience, I might have dismissed them as distant midwife toads Alytes or something else.

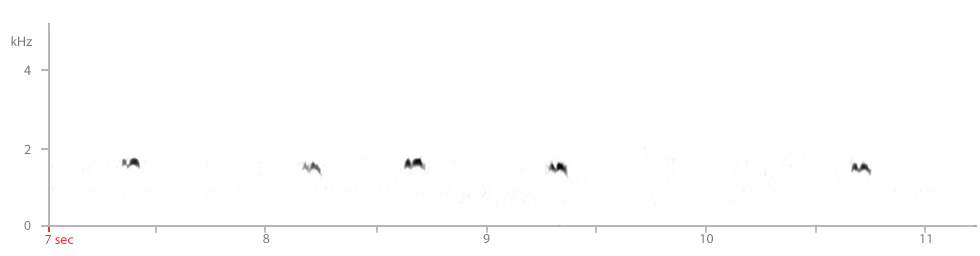

Common Scoter Melanitta nigra, Vale Gonçalinho, Castro Verde, Portugal, 21:25, 11 March 2015 (Magnus Robb). Four male-type calls. Background: Southern Tree Frog Hyla meridionalis.

In Sweden I have recorded migrating Common Scoters in spring on two occasions, but there the phenomenon is much better known. So much so that on 18 April 2012, Håkan Delin told me we could probably expect migrating scoters during the ‘wee hours’ of the morning. It would take them that much of the night to fly from the Swedish west coast, bordering the North Sea, to where we were in Uppland, close to the Gulf of Bothnia. He was right. A flock passed just before 02:00.

Common Scoter Melanitta nigra, Möklinta, Uppland, Sweden, 01:47, 14 April 2012 (Magnus Robb). Background: Ural Owl Strix uralensis.

Locations of the two Portuguese recordings of nocturnally migrating Common Scoter Melanitta nigra, showing assumed direction of travel. 1) Mina de São Domingos, Mértola, Portugal, 22:03, 12 March 2012; 2) Vale Gonçalinho, Castro Verde, Portugal, 21:25, 11 March 2015.

Common Scoter breeds in tundra and northern taiga from Ireland, Scotland, eastern Greenland and Iceland through Scandinavia and across a broad swathe of northern Russia eastward almost as far as the Lena river. It winters at sea in coastal areas from the Baltic Sea, the North Sea and Atlantic coasts from the Lofotens in Norway to Western Sahara. A small population also winters in northernmost parts of the Mediterranean but on the whole, migrations of this species are more east-west than north-south. A very large part of the world population passes through southern Fennoscandia and the Baltic twice a year, traveling between breeding grounds in northern Russia and wintering grounds to the south-west.

Finland is probably the country where you can hear nocturnal migration of Common Scoter at its most impressive. For about two weeks in May each year, this species and Long-tailed Duck Clangula hyemalis account for the great majority of all birds flying over southern Finland at night. Bergman & Donner (1964) studied the phenomenon with radar, both day and night. Many of the scoters commence this leg of their journey at the Bay of Riga, flying over about 120 km of Estonia before crossing the Gulf of Finland. Reaching the south coast, they have to decide whether to turn east along the coast or fly over land. At sea, Common Scoters fly with a mean air speed of 84 km/hour. Over land, where they tend to fly much higher in less dense air, they achieve speeds around 10% faster. With a tailwind, they have even been known to reach ground speeds of up to 170 km/hour.

Breeding and non-breeding range of Common Scoter Melanitta nigra in the Western Palearctic region.

That first time I heard Common Scoters in Portugal they passed at 22:03, having flown a minimum of 52 km from the coast. There was no wind to speak of, and they were not flying high. Assuming a ground speed close to 84 km/hour, based on the low altitude, they would have departed the coast around 37 minutes previously at c21:26. In fact they may have followed the river Guadiana most of the way to where I was. The other time I heard them, I was 73 km from the south coast and they flew over me at 21:25. For sake of argument let’s assume that their air speed was around 84 km/hour again, a conservative estimate for overland flight. At that speed they would have left the coast around 52 minutes previously, at c20:33.

With sunset on the south coast just after 18:30 at that time of year, these flocks’ departures from the coast took place three and two hours after sunset, respectively. Where they actually began their flights is anyone’s guess. It may even have been the Atlantic coast of Morocco. And what about the rest of the night? If they continued until sunrise (c 6:15), the first flock would have flown another 8 hours and 12 minutes and the second flock 8 hours 50. Assuming they gained height and attained a speed closer to 92 km/hour (their mean air speed over land in Finland; Bergman & Donner 1964) they could have flown c754 km and 812 km by sunrise, respectively. The minimum distance from either recording location to the Bay of Biscay is just over 650 km. So even allowing for a sizeable error, an all night flight would be more than enough to cross the entire Iberian peninsula from south to north in a single night. Wow!

With such capabilities, it seems unlikely that Common Scoters restrict overland migration to the Nordic countries and the Iberian peninsula. The species is a well known diurnal passage migrant along the English channel in spring, but Nick Hopper has also recorded nocturnal passage over Portland Bill and Stoborough, Dorset, England, which lies 8 km inland. Between 18 March and 19 April (various years), he has made seven recordings at Portland and one at Stobrough. This is later than either of my two Portuguese inland records but much earlier than the main passage in Finland. Nick also made one recording in autumn, on 6 September 2016.

Interestingly, all but one of Nick’s spring flocks passed by between 23:00 and 00:45 (GMT). This suggests that they may have all flown a roughly similar distance before passing Portland, perhaps coming from the Bay of Biscay. Here is a flock flying over his microphone at Portland on 18 March 2015, at 00:45.

Common Scoter Melanitta nigra, Portland, Dorset, England, 00:43, 18 March 2015 (Nick Hopper). Calls of flock migrating at night.

How many flocks of Common Scoter are passing unnoticed over the British Isles and western France at night? Studying the maps, it seems likely that there could be many.

Comparison with Velvet Scoter and Northern Pintail

Are there any other nocturnal migrants that we could confuse with Common Scoter? Velvet Scoter M fusca is a notoriously silent species; we have struggled to record any of its sounds at all. Males seem to have very inconspicuous calls that sound nothing like Common. The single weak, short call in the following recording seems to be virtually all that males ever produce.

Velvet Scoter Melanitta fusca, Utö, Varsinais-Suomi, Finland, 05:04, 1 June 2015 (Killian Mullarney). Single weak, short ‘cough’ of a displaying male. Background: Common Cuckoo Cuculus canorus, European Robin Erithacus rubecula, Common Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs and Common Reed Bunting Emberiza schoeniclus.

Female Velvet Scoters have much louder calls with a rolled “r” quality about them. Here is a recording from Utö, one of the outermost islets of south-western Finland. In migrating Common Scoter flocks, female calls tend to be conspicuously absent. We have not knowingly recorded females in any of our migration recordings. Having said that, we have not yet recorded any migrating Velvet Scoter at all, let alone Surf Scoter M perspicillata or even rarer scoters from outside Europe. However, we are well aware that American Scoters M americana have much longer whistles than Common Scoters, as you can hear in the recording below.

Velvet Scoter Melanitta fusca, Utö, Varsinais-Suomi, Finland, 05:29, 14 May 2009 (Mark Constantine). Rolled “r” calls of a female in flight. Background: Common Redshank Tringa totanus, Common Gull Larus canus, Arctic Tern Sterna paradisaea and White Wagtail Motacilla alba.

American Scoter Melanitta americana, Seward peninsula, Alaska, USA, 10:36, 2 June 2004 (Arnoud B van den Berg). Whistling display calls of males. Background: Red-necked Phalarope Phalaropus lobatus, Wilson’s Snipe Gallinago delicata, Grey-cheeked Thrush Catharus minimus and Sooty Fox Sparrow Passerella unalaschcensis.

American Scoter Melanitta americana, pair (sound-recorded), Nome, Alaska, USA, 2 June 2004 (Arnoud B van den Berg)

American Scoter Melanitta americana, pair (sound-recorded), Nome, Alaska, USA, 2 June 2004 (Arnoud B van den Berg)

In a European context, the only species that has migration calls likely to cause confusion with Common Scoter is Northern Pintail Anas acuta. Whistles of males are roughly similar in pitch and length to those of Common Scoter. The clear difference, however, is that pintail whistles are disyllabic, recalling a lower-pitched Common Teal A crecca. In sonagrams, you can see a clear difference in shape. At closer range we can hear strange wheezing sounds that accompany the whistles; Common Scoter has nothing remotely similar. Here is a recording of a flock of pintail passing over the Old Town listening station in Poole, Dorset, recorded by Paul Morton.

Northern Pintail Anas acuta, Old Town Poole, Dorset, England, 00:07, 11 March 2017 (Paul Morton). Calls of males in a migrating flock.

Conclusion

Common Scoter is one of those species that helps explain why people can become obsessed with nocturnal migration. It came as a major surprise to hear them so far from the sea in Portugal. However, we now realise that overland flights are something they do regularly. By listening and sound recording at night, we can detect Common Scoters in places where we would never find any during the day, a long, long way from the sea.

References

Bergman, G & Donner, K O 1964. An analysis of the spring migration of the Common Scoter and the Long-tailed Duck in southern Finland. Acta Zoologica Fennica105: 1-59.