Part 2: Put it all together and what have you got?

Magnus, cows and Baillon’s Crake Porzana pusilla, Polder Achteraf, Noord-Holland, Netherlands, 18 August 2005 (Phil Koken). One bird of the pair with young on CD1-43.

When you put timbre, pitch and timing together and give them a stir you get structure and syntax. It has taken me a full 15 years to realise that all the modern approaches to bird identification rely on structure. Moult, topography, biometrics: they are all about structure. Bird sound has structure but you can only see it in a sonagram. Learn to read a sonagram and you are on the road to success.

I learnt many American bird songs from Bruce over several years of competing in the World Series of Birding in New Jersey. He was very good with them, and it was a long time before it dawned on me that because we were well south of his native Newfoundland, he had little experience of many of the songs he was teaching me. “Sonagrams”, he said when I asked him his secret. He had learnt the songs from the tiny sonagrams in the Golden field guide (Robbins et al 1983). Now I’m more familiar with them, it’s still impressive. Not many people do it, but rather like a magician’s trick, once you know how easy it is to do, you want to do it yourself.

Sonagrams are simply graphic illustrations of sound, in the same way that graphs can illustrate a company’s share price. In these and many other kinds of graphs, the lower axis represents time, scanning from left to right. Instead of variations in share price, a sonagram traces the ups and downs of sounds across time. The higher on the page, the higher the pitch; the closer to the base line, the lower the pitch. That’s it! Once you’ve grasped that, everything else is just a luxury.

Most published sonagrams are produced at compatible scales. In this book, we have made them with a scale from 0 to 8 kHz on the vertical frequency axis, or from 0 to 12 kHz when we wanted to include very high frequency sounds. In two further instances we have used 6 kHz and 16 kHz scales to show low and even higher sounds, respectively. In the days before personal computers, published sonagrams tended to cover 2 to 4 seconds on the horizontal time axis, because this was approximately one turn of the cylinder of the original Kay Sona-Graph. Nowadays, to fit everything in without a squeeze, the time on the horizontal can be as long or as short as needed. We have used a variety of time scales throughout the book, but taken care to ensure that sonagrams being compared are at exactly the same scale. As extras, we use colours to help in interpreting the sonagrams, and we can magnify some details to take a closer look. Simple warbler calls are a good start when learning sonagrams. In these four examples of various Phylloscopus warblers, the first has an upward inflection, the second upwards with a kink, the third is flat and the last has a downward inflection.

Simple calls

This first sonagram shows huit calls of a Common Chiffchaff (CD1-13), regularly used by adults. Each call has three layers, and all of them start low to the left and end high to the right, so the call rises in pitch. The three layers are, from the bottom up, the fundamental, first harmonic and second harmonic. These add a little ‘colour’ to the sound, a slight impurity which is very hard to describe, but very easy to hear and see.

CD1-13: Common Chiffchaff Phylloscopus collybita collybita Lascowiec, Podłaskie, Poland, 18:30, 1 May 2005. Calling from deep in roadside bushes, one of two birds. Background: European Robin Erithacus rubecula, Willow Warbler P trochilus and Common Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs. 05.005.MR.14636.01

The corresponding call of a Willow Warbler P trochilus in the next sonagram was recorded when Magnus and Roy Slaterus were looking for a Hazel Grouse Tetrastes bonasia beside the Siemianowka reservoir in north-eastern Poland (CD1-14). This sonagram shows a single, weak harmonic; compared to the chiffchaff’s call this is a purer-sounding whistle. Look at the sonagram and listen for the sudden rise in pitch at the end. This is the best way to tell a Willow Warbler’s from a Common Chiffchaff’s call.

CD1-14: Willow Warbler Phylloscopus trochilus Siemianowka, Podłaskie, Poland, 20:30, 16 June 2005. Typical calls of a bird foraging at dusk. Background: Common Blackbird Turdus merula, Song Thrush T philomelos and Great Reed Warbler Acrocephalus arundinaceus. 05.015.MR.12835.01

Next comes the sonagram of the equivalent calls of wintering Siberian Chiffchaff P tristis recorded at Bharatpur in India (CD1-15). You won’t see any clear inflection in pitch: the sound is flat. These distinctive calls are quite high-pitched, and their harmonics are much less prominent, so when you listen to the recording, you will hear that the tone is a much purer-sounding whistle.

CD1-15: Siberian Chiffchaff Phylloscopus tristis Keoladeo Ghana national park, Bharatpur, Rajasthan, India, 15 January 2002. Typical calls of a bird wintering in bushes along a ditch. Background: juvenile Painted Storks Mycteria leucocephala on the nest. 02.002.MR.11934.01

These typical calls of Iberian Chiffchaff P ibericus (CD1-16) were recorded in a beautiful pine forest along the ancient pilgrim’s path to Santiago de Compostela in north-western Spain. They are distinguished from calls of other chiffchaffs occurring in western Europe by their smooth downward inflection. These calls start at a higher pitch, more or less where the others finish, then drop to where the Willow Warbler starts.

CD1-16: Iberian Chiffchaff Phylloscopus ibericus Erro, Navarra, Spain, 09:19, 26 June 2002. An adult that had been feeding fledged young, calling in open mixed woods with quite a lot of pines on a high hill ridge. Background: Common Wood Pigeon Columba palumbus, Eurasian Wren Troglodytes troglodytes and Common Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs. 02.026.AB.04133.01

Simple song

The first time I realised that I could make my own sonagrams on a lap-top computer I had this shown to me by Swedish birders, Lars Jonsson and Urban Olsson, at the 1993 conference on English bird names organised by Birding World at Swanwick in Derbyshire, England. Urban took his Mac from the hotel safe and Lars whistled the song of a Common Rosefinch Erythrina erythrina (CD1-17) into its mic, and then Urban produced a sonagram. In this case, we’ve had to make do with a real Common Rosefinch as we can no longer afford Lars and Urban. The simple traces on the sonagram are typical of the way song phrases show up on a page.

CD1-17: Common Rosefinch Erythrina erythrina Täktom, Hanko, Uusimaa, Finland, 08:30, 2 July 2003. Song of an adult male. Background: Common Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs. 03.003.DF.13035.11

Inspired by this, I bought a Mac lap-top, and was producing my own sonagrams a short time later. I won’t pretend I found it easy, but it was very satisfying. It meant I could make sound recordings in the field, analyse them at home, and compare them with published recordings and sonagrams. Difficult identifications could be confirmed within hours. If you have a go, don’t forget to use the same scale when comparing any two sonagrams. Once I had started to learn how to use the computer to produce sonagrams, I wanted to use it to answer all the other birding mysteries. What was the difference between Richard’s A richardi, Blyth’s A godlewskii and Tawny Pipit A campestris flight calls? What about Blyth’s Reed A dumetorum, Marsh A palustris and European Reed Warbler calls? Siberian Stonechat Saxicola maurus? Semipalmated Plover C semipalmatus? How did the different gulls sound, and what could I see in their sonagrams? I can’t quite remember how I first started talking to Paul Holt about it all, but I do remember that he had quite a few of these precious recordings that weren’t available on ‘Teach yourself bird sounds’. Blyth’s Pipit flight calls and a variety of Yellow-browed Warbler P inornatus sounds come to mind. But even he didn’t have most of the desired recordings, and we started to talk about a new project, dreaming about collecting all these exciting sounds and publishing something. He came up with the name ‘The Sound Approach’, which with his Burnley vowels seemed to have a w where the u is. Then he went birding in China and hardly came home again.

Now The Sound Approach has many of the recordings Paul and I craved back then, and Magnus and I have chosen a few of our favourites, some intriguing and some just rare examples that illustrate different types of sonagram and, I hope, take bird sound identification a little further. Being able to see small features you hadn’t noticed just through listening is one of the advantages of looking at sonagrams.

‘Curlews’ and proportions in sonagrams

Sitting out at dusk drinking red wine and listening to Stone-curlews Burhinus oedicnemus on a Mediterranean island in the spring, has to be one of the great pleasures in the world. Even more so for sound buffs, for whom noises of the night are always an attraction. The secretive Stone-curlews are often hidden in an orchard or deep grass during the day, and surprise when they call to each other straight after darkness falls. They have varied repertoires and at home, before I had as much experience, I mistook them for Eurasian Oystercatchers Haematopus ostralegus, Eurasian Curlew Numenius arquata and Little Owl Athene noctua. The first call they usually give after sunset is the one that gave them their name. Comparing these two sonagrams shows you the difference in proportions between the commonly heard and sometimes confused sounds of Eurasian Curlew with those of the unrelated Stone-curlew. You can see (and hear) that Eurasian Curlew starts with a long, low note and ends with a short high one (CD1-18), whereas Stone-curlew is the opposite, starting with a short lower one and with a longer, high note at the end (CD1-19).

CD1-18: Eurasian Curlew Numenius arquata Slikken van Bommenede, Zeeland, Netherlands, 20:30, 10 April 2005. Well-spaced currrli calls of a single bird flying over. This individual was not sexed but nearly all of the birds passing through on this date were females. Can be heard after dark. Background: Common Shelduck Tadorna tadorna, Kentish Plover Charadrius alexandrinus, Common Snipe Gallinago gallinago, Sandwich Tern Sterna sandvicensis and Willow Warbler Phylloscopus trochilus. 05.002.MR.11853.01

CD1-19: Stone-curlew Burhinus oedicnemus Kalloni salt pans, Lesvos, Greece, 15 April 2002. Typical cr-leee calls at close range, with some more complex calls of a second bird. Normally heard after dark. Background: Crested Lark Galerida cristata, Tree Pipit Anthus trivialis and Corn Bunting Emberiza calandra. 02.003.KM.12159.01

Kite and pipit calls illustrate modulation

Red Kite Milvus milvus are migrants in Schwaben, Bayern, Germany, and the locals look forward to their return in the way other Europeans wait for Common Cuckoo Cuculus canorus. I stayed with Diana Krautter who can whistle the ‘Milan’ into circling her as she watches from her garden. This bird was following the plough and calling to passing birds. The modulation in this Red Kite’s call (CD1-20) is very slow and easy to hear (aye aye aye) and visible in the sonagram.

CD1-20: Red Kite Milvus milvus Near Bodensee, Germany, 17:00, 31 May 2005. Calling while following the plough. Background: House Sparrow Passer domesticus and Common Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs. 05.012.MC.01220.31

This Black-eared Kite M lineatus (CD1-21) was recorded in the north of Japan where in winter many roost on the edge of frozen lakes. Japanese fishermen carve fishing holes in the ice and the kites hope for scraps. They often mob the Steller’s Sea Eagles Haliaeetus pelagicus and White-tailed Eagles H albicilla as they all look for fish remains. This note has a much faster modulation that sounds like a neigh of a horse.

CD1-21: Black-eared Kite Milvus lineatus Nimuro, Hokkaido, Japan, 9 February 2005. Calling just after dawn. Background: a pair of Steller’s Sea Eagles Haliaeetus pelagicus and some Jungle Crows Corvus macrorhynchos japonensis. 05.001.MC.04928.02

The flight sounds of Richard’s, Tawny and Blyth’s Pipits are like three quizzes with beginner, intermediate and advanced: Richard’s Pipit has a diagnostic call used in flight that makes it very good to learn. Let’s call it squonk. The great thing about Richard’s Pipit is that when it passes overhead you can hear it coming a long way off and disappearing for quite a while so you can get your mind around the sound (CD1-22). This sound doesn’t vary much; it can be given singly or in twos or threes, and most of the variation you hear is caused by distance. As you can see, sonagrams give us several additional characters to look and listen for. In this case, how ‘buzzy’ it sounds is a reflection on the modulations in the call: much faster than either of the kites. The buzzy quality is especially coarse and obvious in Richard’s, where this has pronounced modulation, showing as ‘shark’s teeth’ on a sonagram.

CD1-22: Richard’s Pipit Anthus richardi IJmuiden, Noord-Holland, Netherlands, 09:04, 29 October 2005. Typical calls of a bird migrating along the Dutch coast: squonk. Background: European Robin Erithacus rubecula, Goldcrest Regulus regulus, Great Tit Parus major, European Blue Tit Cyanistes caeruleus and Common Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs. 05.029.MR.11126.23

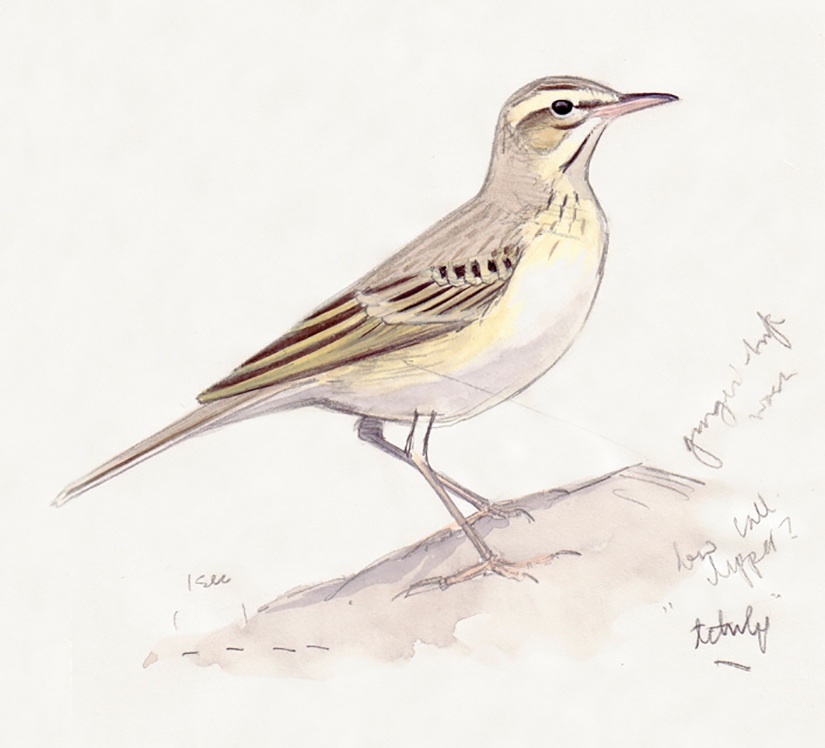

Tawny Pipit Anthus campestris, adult, Eilat, Israel, 12 November 1992 (Killian Mullarney)

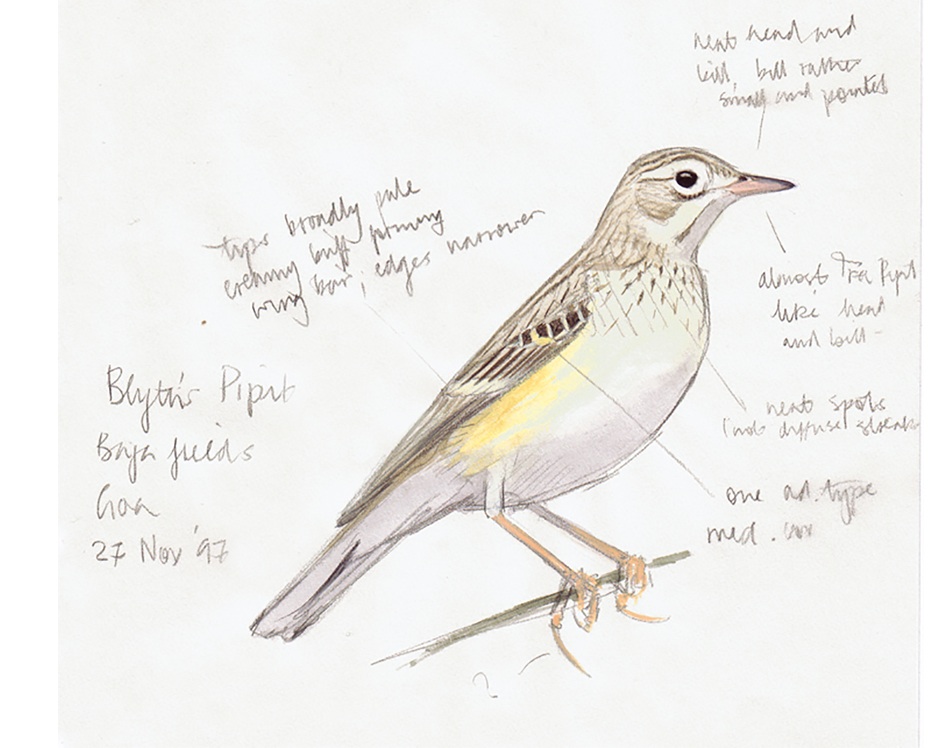

Blyth’s Pipit Anthus godlewskii, first- winter, Goa, India, 27 November 1997 (Killian Mullarney)

Tawny Pipits can be a little trickier, as they show a lot more variation (CD1-23). The next two recordings were made by Killian whose field notes describe the equivalent call of Tawny as “a strongly downslurred tsleeuu, a fuller, slightly longer note than a similar call of House Sparrow, reminiscent of Yellow Wagtail but not really confusable with it”. This is the call he associates most with birds in full flight; “flushed birds may give it too, but it is often preceded or interspersed with a rapid series tchilp-tchelp-tchilp.. notes, not unlike the usual take-off call of Short-toed Lark”. Now check the sonagram; first notice the variation in sounds, the downslurred shape of the sound, then the pitch compared to Richard’s Pipit. In Tawny’s tsleeuu the modulated bits are so brief that they have very little bearing on the timbre of the call as a whole, leaving the sound slightly musical as an attractive note, or as Killian referred to it “a real call”.

CD1-23a: Tawny Pipit Anthus campestris Sohar Sun Farms, Al Batinah, Oman. 27 October 2003. Tsleeuu calls of a bird in flight. 03.016.KM.05500.02

CD1-23b: Tawny Pipit Anthus campestris Sohar Sun Farms, Al Batinah, Oman. 20 October 2003. Two types of calls on flushing, a single tsleeuu, then a series of short chip calls. Background of both recordings: Crested Lark Galerida cristata. 03.014.KM.13135.12

One of the reasons Blyth’s Pipit counts as advanced is that it’s extremely rare throughout the Western Palearctic, and conse-quently much sought after. Like Tawny Pipit, Blyth’s has a variety of sounds it uses in flight (CD1-24). Comparing Blyth’s to Tawny, Killian added: “most of the time it’s just an unobtrusive and extremely Tawny Pipit-like typp typp typp typp every half second or so. If you are lucky enough to hear the full call, when it gets into its stride, its squonk equivalent is an emphatic speuu, a little higher-pitched than Richard’s”. You can see this on the sonagram and that the modulation is so rapid and fine that it results in a wheezing quality, or as Killian describes “not so throaty as Richard’s, cleaner, more like Yellow Wagtail”.

CD1-24: Blyth’s Pipit Anthus godlewskii Baga fields, Goa, India, 16:00, 10 November 2001. First longer speuu calls, then short calls like chip of Tawny Pipit. Background: House Crow Corvus splendens. 01.011.KM.02835.01 & 01.011.KM.03900.01

Broadband and Trumpeter Finches

Having looked at modulations, time for some fun. In the first sonagrams of the book, we already noted that adding layers of harmonics to a simple, pure-sounding linear whistle changes the timbre, but what happens when this is taken to extremes? When we started The Sound Approach, one of the most exciting prospects was to make recordings of Western Palearctic species that had never been included in audio publications before. Mongolian Finch Bucanetes mongolicus was one of these. It has various songs, and the most lyrical one recorded at the ruined Ishak Pasha palace in eastern Turkey near the border with Iran (CD1-25) sounds like a cross between a Common Linnet Linaria cannabina and a Common Rosefinch. In the sonagram you can see several layers of harmonics, giving it a somewhat squeaky timbre, but this is nothing compared to the amazing timbre of a Trumpeter Finch B githagineus, its desert counterpart (CD1-26). This was recorded in India in January 2002, close to the Pakistani border, with the two countries on the brink of war and Magnus trying to look unobtrusive, despite the parabola in hand, every time a military vehicle passed by. The Trumpeter Finch sounds as if he saw the funny side of all this. Look at the incredible profusion of layers in the sonagram: this cool little desert creature has been into ‘broadband’ for thousands of years.

CD1-25: Mongolian Finch Bucanetes mongolicus Ishak Pasha palace, Agrı, Turkey, 8 June 2002. Song of an adult male. Background: Corn Bunting Emberiza calandra and souslik Spermophilus. 02.033.MR.13641.11

CD1-26: Trumpeter Finch Bucanetes githagineus Wood Fossil Park, Jaisalmer, Rajasthan, India, 24 January 2002. Song of an adult male. Background: Common Babbler Turdoides caudatus. 02.005.MR.04255.03

Shapes and Yellow-browed

comparisons

Few people get Yellow-browed Warblers in their garden, so Arnoud was lucky when he recorded this one in a Bird Cherry Prunus padus in his garden at Santpoort-Zuid, the Netherlands (CD1-27). Compare the sonagram with one of a Coal Tit Periparus ater recorded at nearby IJmuiden, as it perched briefly before continuing on a migration flight (CD1-28). These two sounds are commonly confused; both are high-pitched and show a V-shape in sonagrams. As you can see, however, the Coal Tit’s calls are a shorter, more rounded V-shape and it tends to double its calls, whereas the Yellow-browed does not. Now compare both to a Pallas’s Leaf Warbler P proregulus recorded by Arnoud, surrounded by curious children, in the middle of town near Rotterdam (CD1-29). The harmonics you can see in the sonagram create a similar quality to chiffchaff, but the rapid descent at the start, gives it a more of a t– or ch– sound. Both these qualities also separate it from Yellow-browed and Coal, and it is also lower-pitched. All a bit technical? Try Anthony’s and Killian’s more artful description, dreamt up when they first heard Pallas’s Leaf Warbler in China; they compared Pallas’s calls to “the twang sound when you skid a piece of ice across a frozen pond”.

Yellow-browed Warbler Phylloscopus inornatus, first-winter, in suburban garden at Santpoort-Zuid, Noord-Holland, Netherlands, 7 October 2000 (Arnoud B van den Berg). Same bird as on CD1-27.

CD1-27: Yellow-browed Warbler Phylloscopus inornatus Santpoort-Zuid, Noord-Holland, Netherlands, 15:05, 7 October 2000. Typical calls by a first-winter migrant recorded in, less typically, a suburban garden 6 km inland. Background: Great Tit Parus major. 00.009.AB.04333.01

CD1-28: Coal Tit Periparus ater IJmuiden, Noord-Holland, Netherlands, 21 September 2005. Calls of two birds perched briefly in a willow before continuing on their migration flight. The birds were heading north, part of an invasion that allegedly originated in central Europe. Background: Dunnock Prunella modularis, European Blue Tit Cyanistes caeruleus and Eurasian Magpie Pica pica. 05.025.MR.15406.02

CD1-29: Pallas’s Leaf Warbler Phylloscopus proregulus Vlaardingen, Zuid-Holland, Netherlands, 11:35, 1 April 2002. Typical calls by a presumed first-winter male in, less typically, a suburban street. Background: Great Tit Parus major. 01.002.AB.00725.01

M shapes in Common Ringed and Semipalmated

In the summer of 2004, we sent Magnus to Siberia, Russia. He liked it so much he missed his plane home and had to wait five days for the next one. This gave him the opportunity to make lots of Common Ringed Plover recordings. A few weeks earlier, Arnoud travelling with René Pop through Alaska, USA, found, photographed and sound recorded a Semipalmated Plover sitting beside the old road from Nome to the Eskimo village of Teller. Look at the sonagram as you listen to the sounds. These Common Ringed calls (CD1-30) have a simple rising inflection as you can see. In Semipalmated, the equivalent call is higher-pitched, has stronger inflections, and is M-shaped with a downward dip in the middle (CD1-31). Looking at the sonagram and listening to the CD does really help in understanding these differences but it is hard to put them into words.

CD1-30: Common Ringed Plover Charadrius hiaticula tundrae Tiksi, Yakutia, Russia, 2 July 2004. Calls of ‘flight call’ type; an adult standing its ground on its breeding territory. Background: Common Snipe Gallinago gallinago, Coues’s Arctic Redpoll Acanthis hornemanni exilipes and Snow Bunting Plectrophenax nivalis. 04.036.MR.10124.01

CD1-31: Semipalmated Plover Charadrius semipalmatus Between Nome and Teller, Seward Peninsula, Alaska, USA, 10:46, 4 June 2004. Calls of ‘flight call’ type; an adult recorded near a nest with eggs, first standing its ground, then taking off. Background: Long-tailed Jaeger Stercorarius longicaudatus. 04.015.AB.01950.10

Semipalmated Plover Charadrius semipalmatus, adult female, between Nome and Teller, Seward Peninsula, Alaska, USA, 4 June 2004 (René Pop). Same bird as on CD1-31.

Separating stonechats by inflection

European Stonechat S rubicola has a variety of calls, and the most common are a chat, often compared to the sound of two stones being tapped together, and a whistled weet with an upward inflection (CD1-32). These are easy to see on a sonagram: the chats are vertical lines and the weets diagonal. The two are often given in alternation, with chat tending to take over from weet in the autumn. While in Kazakhstan, Magnus thought he noticed that the whistled sound in Siberian Stonechat had a downward inflection: wiu (CD1-33). The sonagram confirms the point nicely and the recordings support these observations. You can see the vertical trace produced by chat sounds interspersed with upward and downward inflected weet and wiu calls, respectively

CD1-32: European Stonechat Saxicola rubicola North Hoy, Orkney, Scotland, 5 July 2001. Weet and chat calls of adult male, with more distant female. Background: Eurasian Curlew Numenius arquata and a colony of Common Gulls Larus canus. 01.030.MR.00433.00

CD1-33: Siberian Stonechat Saxicola maurus Steppes near Korgalzhyn, Aqmola Oblast, Kazakhstan, 25 May 2003. Wiu and chat calls of an adult male. Background: Common Quail Coturnix coturnix, White-winged Lark Melanocorypha leucoptera, Eurasian Skylark Alauda arvensis, Sykes’s Blue-headed Wagtail Motacilla flava beema and Booted Warbler Acrocephalus caligatus. 03.021.MR.12120.11

Rattles of Red-breasted Flycatchers

Rattles show in sonagrams as a series of the vertical chat or tick traces you’ve just learnt. These three sonagrams show the differences between rattling calls of Eurasian Wren Troglodytes troglodytes, Red-breasted Flycatcher Ficedula parva and Taiga Flycatcher F albicilla. In Red-breasted Flycatcher (CD1-34), the individual ticks are very evenly spaced; in Eurasian Wren (CD1-35), the ticks are not evenly spaced, but closer together at the start of each rattle. The flycatcher’s rattle is also slower, in other words its ticks are spaced further apart. We can also use sonagrams to separate Red-breasted from Taiga Flycatcher (CD1-36), its recently split counterpart breeding from the Urals eastwards and occurring as a vagrant in Europe. In both flycatchers, the rattle is of roughly similar length, but in Taiga it contains many more ticks with much shorter gaps between them, and it slows down slightly towards the end. The resulting rattle is so different from that of Red-breasted that, as you can see in the sonagrams, Eurasian Wren fits in between.

CD1-34: Red-breasted Flycatcher Ficedula parva Keoladeo Ghana national park, Bharatpur, Rajasthan, India, 16 January 2002. Very neat and regular rattling calls, a male more than one year old on the wintering grounds. Background: Gadwall Anas strepera, Rose-ringed Parakeet Psittacula krameri, Olive-backed Pipit Anthus hodgsoni, Bluethroat Luscinia svecica, Purple Sunbird Nectarinia asiatica and voices of rickshaw drivers. 02.003.MR.05646.01

CD1-35: Eurasian Wren Troglodytes troglodytes IJmuiden, Noord-Holland, Netherlands, 30 October 2002. Typically varied rattling calls. Background: migrating Eurasian Skylark Alauda arvensis. 02.051.MR.13058.01

CD1-36: Taiga Flycatcher Ficedula albicilla Keoladeo Ghana national park, Bharatpur, Rajasthan, India, 17 January 2002. Typical creaking rattles of a bird on the wintering grounds. Background: Rose-ringed Parakeet Psittacula krameri, White-throated Kingfisher Halcyon smyrnensis and Oriental Magpie Robin Copsychus saularis. 02.003.MR.12423.01

Gull long calls

Gull sounds are always with us, at least in western Europe, and for me living by the sea they can change a rather boring meeting into something quite bearable. Male and female Herring Gulls Larus argentatus stand on the roof opposite my office in Poole, Dorset, and pass opinion on every bird flying overhead. The most helpful sound to listen for is the long call, effectively the song of a gull. It can be heard at any time of the year, but particularly from adults and near-adults in late winter and during the breeding season. This one was recorded in March at a quiet spot in the Netherlands (CD1-37). These sonagrams are more complex than any you have tried so far. Cut them into pieces and they are much easier to understand. There are three separate stages to the long call, each with the gull adopting a different stance, and I hope that visualising these will help when reading the sonagrams. First, there are a few fairly low, short notes as the bird stretches its head a little forward. Then some longer, comparatively high-pitched notes are produced with the head pointing downwards. Finally the head is jerked upwards (in Herring Gull around 45º above the horizontal) and a long, loud series of fairly short, trumpeting notes are belted out.

CD1-37: Herring Gull Larus argentatus Northern shore of Grevelingen, Zuid-Holland, Netherlands, 26 March 2003. Long call of an adult. Background: Mallard Anas platyrhynchos, other Herring Gulls and Dunnock Prunella modularis. 03.006.MR.15807.30

In April 2003, Jacek Betleja took a group of us with him as he checked the breeding colony of Caspian Gulls L cachinnans at Babice in southern Poland (CD1-38). Having criticised field guide authors earlier on for their use of adjectives, I am going to have a go at describing something most of them ignore: Caspian Gull sounds. Caspian is the tenor to Herring Gull’s alto and as you can see in the sonagram Caspian’s long calls have the same three stages but the notes are deeper and richer in harmonics. After a few introductory calls, the long screamed notes of the second part sound as if it is straining for the Herring Gull’s higher pitch while bowing much deeper. Next, the head is thrown all the way up to the vertical as it ‘laughs’ (cachinnans means ‘laughing’). After the screamed middle, this diabolical cackling adds to the call’s grotesque character. This is because of the speed of the notes, which you can compare with sonagrams of Herring and Yellow-legged Gulls L michahellis. Unlike both, a standing Caspian often opens its wings in an albatross-like posture while performing the long call. The recording was an adult giving two long calls while flying over its breeding colony. Long calls sound the same whether they are given in flight or on the ground.

CD1-38: Caspian Gull Larus cachinnans Babice, Chrzanow, Poland, 14:52, 25 April 2003. Long calls in flight. Background: Black-headed Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus. 03.009.AB.02150.01

Jacek Betleja and Bruce Mactavish ringing an adult Caspian Gull Larus cachinnans at breeding colony, Babice, Jankowice, Chrzanow, Poland, 25 April 2003 (Arnoud B van den Berg)

Caspian Gull Larus cachinnans, adult, Babice, Jankowice, Chrzanow, Poland, 25 April 2003 (Arnoud B van den Berg). Regularly making the long call in flight while circling above its breeding colony on an islet along the Wisla river.

Apart from cheering up a dull meeting, another reason for listening to the gulls at work is that there is always a chance that I’ll hear a Yellow-legged Gull, as Poole is its only British breeding site. In summer we get a good influx here; the local pie factory and surroundings are home to over a hundred, and they substantially outnumber Lesser Black-backed Gulls L fuscus. Yellow-legged (CD1-39) has a long call that is uniformly deeper than that of Caspian Gull, with softer introductory notes and a far slower delivery, replacing all the maniacal qualities with sounds delivered at a pace you would expect from a bird that sits around eating pies all summer. The long call gestures are similar to Caspian but less exaggerated. Again, the sonagram gives you an impression of the speed of delivery. The length of long calls varies considerably in all gull species, while the speed of delivery and pitch do not.

CD1-39: Yellow-legged Gull Larus michahellis Islote de Benidorm, País Valenciano, Spain, 7 August 2002. Long calls of a flock, mainly adults, socialising in flight before going to roost. 02.037.MR.14101.01

Finally, here is a sonagram of a long call from a Lesser Black-backed Gull (CD1-40) for you to practice.

CD1-40: Lesser Black-backed Gull Larus fuscus IJmuiden, Noord-Holland, Netherlands, 10:18, 25 August 2000. A pair with one offspring flying past: long calls of an adult, kow calls of the other and whistled begging calls of the juvenile. 00.045.MR.00000.01

Loudness and intensity

The final measurement of bird sounds that we will consider is their loudness or quietness. In the same way that pitch relates to frequency, loudness is a word for how we perceive intensity, which is measured in decibels or dB. How loud a sound seems depends not only on the effort put into making it, but also on its pitch, and the prevalent acoustics, including any other sounds audible at the same time.

Loudness is shown in a sonagram by the depth of black in the tracing. When the sonagram is set to ‘greyscale’, a quiet whistle will show as a narrow, light grey line, whereas a loud one will be thicker and blacker. When judging loudness in a sonagram, it is wise to use the darkness of the tracing comparatively – and thus judge the louder parts of a song or call only in comparison with other parts of the same sonagram. A sonagram from another recording may not have been made from the same distance, or with the same equipment.

A helpful graph for illustrating loudness and timing is an oscillogram. It measures the sound waves. Their size above or below the horizontal axis tells us how loud the sound is. As usual, their change over time is read from left to right. Because a 1 kHz sound has 1000 waves per second, you have to zoom in a very long way to see that kind of detail. We don’t need to see the individual waves; we can use oscillograms to see how the patterns of loudness change over time, and the rhythm or timing of the sounds.

Comparing woodpecker drums by oscillogram

Listen to typical drums of male Great Spotted Woodpecker Dendrocopos major (CD1-41) and male Lesser Spotted Woodpecker D minor (CD1-42). Compare what you hear: the differences in duration, the way loudness changes or stays the same over the course of the drum (the envelope), and the strike-rate in the individual drums. Now check these elements against the oscillogram. An additional difference not visible on these oscillograms is the length of the pauses between drums, which is much longer in the Great Spotted.

CD1-41: Great Spotted Woodpecker Dendrocopos major Biebrza marshes, Podłaskie, Poland, 07:21, 22 April 2003. Drumming of a male. Background: Common Wood Pigeon Columba palumbus, Common Chiffchaff Phylloscopus collybita, European Blue Tit Cyanistes caeruleus and Common Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs. 03.008.AB.05644.00

CD1-42: Lesser Spotted Woodpecker Dendrocopos minor Biebrza marshes, Podłaskie, Poland, 18:30, 1 May 2005. Drumming of a male. Background: Blackcap Sylvia atricapilla, Wood Warbler Phylloscopus sibilatrix, Common Chiffchaff P collybita, European Blue Tit Cyanistes caeruleus, Great Tit Parus major and Common Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs. 05.005.MR.14339.01

Baillon’s Crakes’ emotions

Birds produce strong and weak sounds depending on the distance their message is intended to travel and the meaning they want to convey. Most birds produce weak, short-distance sounds when subsinging, copulating or comforting young, for example. Stronger, long-distance sounds are used to advertise for a mate, defend territory, contact others or mob a predator. Emotion always plays a part in this and many bird sounds increase in strength and change pitch depending on the emotional state. Listen to the recording of an adult Baillon’s Crake Porzana pusilla (CD1-43), leading its young along a ditch. The continuously repeated weak tuc… tuc… tuc… calls it uses to keep the brood together gradually morph into louder (from 0:31) tak! calls as it senses danger (in this case the danger was Magnus). These louder calls are presumably not only intended for its young less than a metre away, but also for its mate about 10 m further along the ditch.

Baillon’s Crake Porzana pusilla, Polder Achteraf, Noord-Holland, Netherlands, 18 August 2005 (Phil Koken). One bird of the pair with young on CD1-43.

CD1-43: Baillon’s Crake Porzana pusilla Polder Achteraf, Noord-Holland, Netherlands, 08:11, 18 August 2005. An adult leading about four tiny calling young along a ditch. You should be able to hear them move from left to right. Background: Greylag Goose Anser anser. 05.024.MR.01234.11

The power of a Thrush Nightingale

How loud a given sound seems to be depends on the acoustic conditions and the distance from the bird, as well as the direction the bird is facing. Describe each sound separately, and try to avoid unqualified use of the words ‘loud’ and ‘soft’. Powerful, moderate and weak are more meaningful words to describe the power at which sound is produced. A flock of Greater Canada Geese Branta canadensis, with their low-pitched calls, flying over a house at dawn could wake the inhabitants, whereas the loud, high-pitched calls of a large flock of Redwings T iliacus would not, even if they were much closer. The calls of both species in flight can be described as loud, but only Greater Canada calls can be described as powerful. Listen to this Thrush Nightingale Luscinia luscinia as it sings from a small island in a pond in the town park of Białowieza, Poland (CD1-44). The power of the song dominates over even closer songs of Eurasian Wryneck Jynx torquilla, Common Wood Pigeon C palumbus, Eurasian Collared Dove Streptopelia decaocto, Great Reed Warbler A arundinaceus and Common Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs. It held my attention so well I didn’t notice the Icterine Warbler Hippolais icterina song that you can hear in the recording.

CD1-44: Thrush Nightingale Luscinia luscinia Białowieza village, Podłaskie, Poland, 05:44, 3 May 2005. Song; ambient recording with dawn chorus. Background: Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos, Eurasian Collared Dove Streptopelia decaocto, Eurasian Wryneck Jynx torquilla, Great Reed Warbler Acrocephalus arundinaceus, Icterine Warbler Hippolais icterina, Common Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs and European Greenfinch Chloris chloris. 05.007.MC.11241.01

It is also worth noting that sounds learnt from published tapes and CDs can often give the wrong impression regarding the loudness of the sound; the birds invariably seem weaker when heard in the field. Previous bird sound publications have often been ‘mastered’ by people who did not have any field experience of the sounds, and set them all to play at the same volume.