The next wave of folk who came to the pub started with local lad James Lidster, who Mo and I met while birding. He told us he had a forklift license, so despite him being a birder and potentially unreliable, he came to work with us. A great rarity finder, he pinned down the first twitchable Icterine Warbler on Ballard. I was delighted, and was sitting there trying to sketch it when Nick Hopper wandered up and looked over my shoulder. He cheekily asked me which bird I was drawing. It was 9 September 1997, a Tuesday, which says a lot about both of us. Nick had just moved to Poole, having run up too many unpaid parking tickets in Bath, and I invited him down to the pub. James had a close birding friend called Ian Stanley who had also moved into the area, and this completed the trio. They shared a flat together on Poole High Street.

When Nick was little, his mum took him to church a couple of times and he tried Sunday school once but didn’t like it. As a boy, I was primarily educated at a Church of England school and sang in the church choir twice on Sundays. He seems to have a better grasp on prehistory than I do. Had I been asked down the pub, “what is the age of the earth?” the first answer that popped into my head would have been, “about 6,000 years plus seven days”. This is a creationist view that was subtly introduced to churchgoers of my age, and could be worth a spin if it weren’t for Ian Lewis’s Wikipedian superpowers. He could point out, and has, that the current scientific consensus on the age of the earth seems to be around 4.5 billion years. I can remember him explaining how ‘climate change’ was a constant reality with the temperatures varying from Arctic to Mediterranean, and that before the current worries about warming we thought we were heading into an ice age.

I must also admit to thinking that the ice age was just that, a period of time when everything was ice (and by everything I mean Poole Harbour). Now I realise that you have to go back around 640 million years to find our area completely covered in ice.

Anyway, I’m not a creationist in this religious debate. I also believe that Poole’s climate has constantly changed. I find it a bit harder to believe that scientists can calculate accurately something as complex as man’s influence on the earth’s weather, or that politicians can co-operate enough to control it, but that’s another subject. Climate scientists often seem to have little in common with meteorologists, and in many ways they seem closer to archeologists. For example, they use compilations of 26,000 years of tree ring history to work out the ancient changes in the weather. They also take deep samples of soil deposits, analysing the grains of pollen to reconstruct the dominant vegetation and likely temperatures stretching back thousands of years into the past.

We can also learn much about the ancient climate from bird bones, fossilised insects, and teeth from a variety of creatures, all of which can be identified and carbon dated. Take the crocodiles. They became extinct in Poole Harbour 100 million years ago. We know that crocs were out there, because when you search Poole Harbour mud you can still find their teeth.

For more recent time scales, the picture is less muddy and to imagine birding in Poole in the last 100,000 years we recommend Birds and Climate Change (1995) where John Burton, a modern Sherlock Holmes, describes the amazing changes to Britain’s birdlife over the millennia. When we read Burton’s book alongside The History of British Birds by Yalden & Albarella (2009), the amazing list of birds for Poole Harbour makes Nick and me hyperventilate.

Evidently, 65,000 years ago Willow Grouse and Little Bustard would have been here. Their remains were found just west of us at Tornewton cave in Devon. Some 45,000 years ago, the climate became far warmer. Poole’s acid soil isn’t perfect for preserving tiny skeletons, and the nearest discovered remains from this period were further north, where there were White Stork, Alpine Swift and Crag Martin.

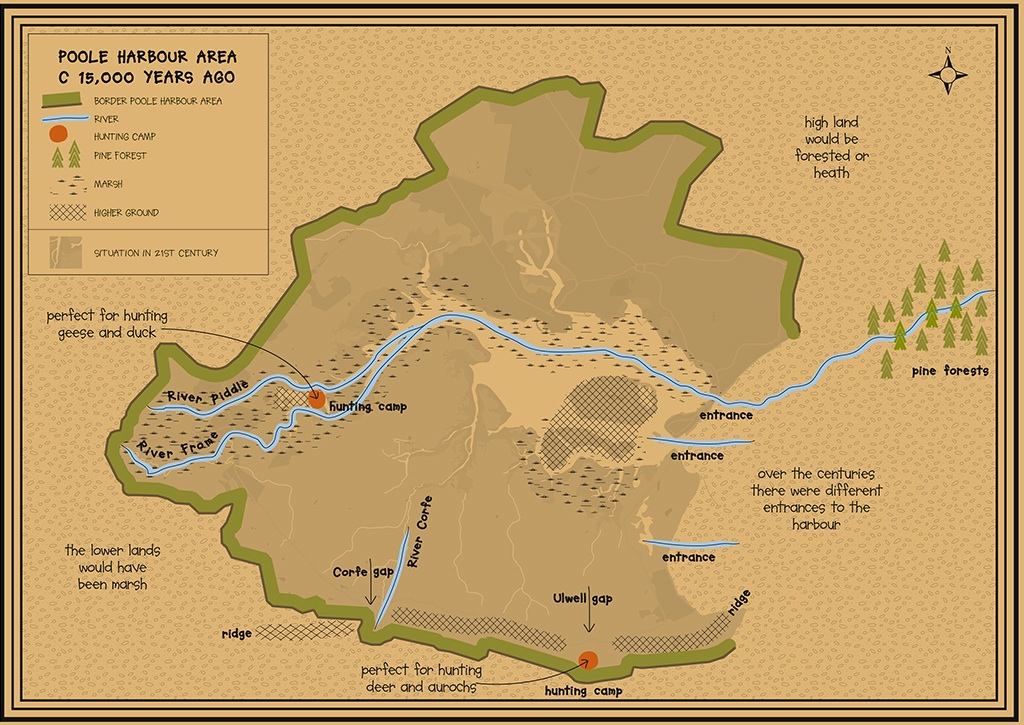

Between 22,000 and 17,000 years ago came another spell of cooling temperatures. This was the ‘Last Glacial Maximum’, which saw an ice sheet extend southwards to within 500 km of Poole. Massive amounts of seawater were ‘locked up’ in the ice caps, lowering sea levels by an estimated 127 m. At this time, Britain was a part of a large continental land mass and the area that is now Poole Harbour was just a floodplain with a river running through it, a tributary to another more distant river. Not only the harbour, but also the English Channel and much of the North Sea were dry land.

Our local patch, like all of southern Britain, had become a semi-polar desert, uninhabited by man and home to birds and beasts you would now associate with the far north. Arctic Fox, Woolly Mammoth and Collared Lemming remains dated to this period have been found in nearby counties. Presumably, Rock Ptarmigan, Gyrfalcon, Snowy Owl and Snow Bunting would have been around, and some northern waders would have bred in the area.

The continuing cold pushed deciduous woodland, its birds and mammals (including mankind) further and further southwards, concentrating them into ever shrinking areas that eventually became a few isolated pockets. These pockets or ‘refugia’ included the Iberian Peninsula, the Balkans and Ukraine. During this period of isolation, the birds in each ‘refugium’ essentially formed ‘island populations’, following their own independent evolutionary course. When the climate eventually warmed up, as the bird populations spread from their separate refugia and reunited, they were often no longer compatible. Over the course of several glacial cycles, this led to new species being formed.

By 13,000 years ago, the last ice age was fast losing its grip and the ice sheet was retreating back northward, taking its Arctic conditions with it. Poole Harbour was now no longer a semi‑polar desert, but at least partly covered in forest, with scattered lakes and bogs, a landscape akin to today’s Finland and with birdlife to match. Nick loves the list of rare birds that would have been hanging around the area, with Nutcrackers occupying his garden up Nutcrack Lane, and other gems like Willow Grouse, Hazel Hen, Hawk Owl and Tengmalm’s Owl nearby.

Humans also spread north after the last ice age. There was a population explosion, and Britain was repopulated with hunters. Stephen Oppenheimer specialises in a new branch of science called phylogeography, or whose ancestors came from where, and when. In The Origins of the British (2006), he describes his research into our genes. He suggests that my south coast ancestors were most likely Paleolithic hunter-gatherers who had been successfully killing mammoths in the treeless steppe tundra of what is now Ukraine. Since there was no English Channel, they could have walked in a straight line all the way. In practice they preferred to move along watercourses, hunting and fishing like ancient strandlopers. Nick’s Somerset ancestors most probably came up the Atlantic coast from a human refugium in the Basque country, along with those who settled in Wales and Ireland. Nick loves the sea, and both his granddad and great granddad were in the navy, so he feels at home with this idea. Oppenheimer also suggests that despite repeated invasions, the genes of these early arrivals typically still predominate close to where they settled.

Lillian Ladle and her fellow archeologists ran one of Britain’s longest running amateur digs near Wareham. At Bestwall between the rivers Frome and Piddle, they found the remains of one of the early settlers’ camps, dating from around 11,000 years ago. The semi-nomadic hunters had dug holes through to the gravel and worked the flint nodules into sharp stone tools and arrowheads. They made the most of the fishing, collected shellfish, and hunted Red-breasted Mergansers, Great Bitterns, Great Crested Grebes, Little Grebes and Common Cranes (Ladle & Woodward 2009).

Over the next few thousand years, things got drier and temperatures continued to increase until they peaked at between 9,000-7,000 years ago. Strawberry Tree, Spotted Slug, European Bee-eater, Eurasian Hoopoe and Dartford Warbler appeared with this Mediterranean climate. Around the time, the gradual melting of the ice had raised sea levels to the point that the land connection between Britain and France disappeared. Then about 8,000 years ago, a huge undersea landslide off the Norwegian coast caused a massive tsunami. This almost certainly contributed to the disappearance of low‑lying Doggerland, the last remaining dry land in the southern North Sea (Weninger et al 2008). Britain became an island, and Poole was now on the coast.

The shallow dish of the Stour and Piddle flood plain formed a huge harbour, the silt forming deep and treacherous mud flats between the hilltops, which were now islands poking out of the water. Over time, the surrounding ridge of hills gradually eroded away, leaving the chalk stacks called Old Harry and his wife, a gap that is Poole Bay, and 24 km east of Old Harry, the corresponding chalk stacks of The Needles on the newly formed Isle of Wight. The soft sandy cliffs along the new seashore soon crumbled and deposited tons of sand, and over the next 7,000 years this formed the beaches and harbour mouth. This is how Poole Harbour was formed, the largest and shallowest natural harbour in Europe.

Climate change concerns more than just temperature and is really about the changes in weather patterns created by the relative distribution of sea and land, ice packs and deserts. Now that Britain was surrounded by water, its weather became more anticyclonic. All this disrupted the birds’ habits. It also stranded the Dartford Warbler.

Dartfords would have bred in the bush undergrowth on the edge of pines or in scrub along the harbour shores. There were no open heaths yet according to soil deposits. Pollen samples taken at the Bestwall dig showed how at first junipers were common, then birch arrived and was succeeded in turn by pine, oak and elm as the climate became warmer, while lime and alders grew along the wetter meadows. This creates a glorious picture of bird-filled forests with very few people, and Dartfords singing along the margins.

Starting around 5,000 years ago, our ancestors felled the forests to farm the crops that began to account for half the pollen samples in the deposits. Evidently, 3,500 years ago the land was divided into fields where barley, wheat and beans were cultivated and sheep and cattle kept. Red Kites, Ravens, Carrion Crows, Jackdaws and Starlings would have thrived as they learnt to exploit our husbandry. Most of the soil outside the richer river valleys was soon exhausted, and it was this environmental catastrophe that left us with Poole’s heathland.

Poole Harbour 2,000 years ago would have been more like an estuary than today, with three entrances to the harbour: one south of Pilot’s Point and a second in the middle near today’s entrance. A third recently discovered entrance is now deep under Panorama Road, a couple of hundred yards before it reaches the chain ferry, where the North Channel flowed out into Poole Bay (Dyer & Darvill 2010).

An archeological dig on and around Green Island was televised on Channel 4’s Time Team (Taylor 2004). It found evidence of a thriving trade and most exciting for us, in amongst the pots and amphoras, the remains of a White-tailed Eagle. Around 2,200 years ago, the area nearby would have had an industrial feel with shale working, iron working, clay mining and pottery production, and salt production centred on Ower. Cross-channel boats would have been moored to a substantial dock between Ower and Green Island. The archeologists also discovered that pigs were slaughtered, butchered and salted, so maybe this attracted the eagle. The leftovers would certainly have fed hundreds of large gulls.

In fact salt production was to become a major feature around the southern shores of the harbour for some time to come. The warm climate was ideal, and saltpans were soon popping up all over the place. There were around 50-100 acres at Arne alone with many more in Brand’s Bay and at least 32 pans in Studland Bay. One can assume it was a typical Mediterranean scene with breeding Red-crested Pochards, Black-winged Stilts, Kentish and Little Ringed Plovers, and Black Terns. Although the climate did subsequently cool, salt production was able to be maintained for the next thousand years by heating the water with shale.

The best addition to our ancient bird list has to be the Dalmatian Pelican. With a colony only 80 km away on the Somerset Levels, I think we can assume a few young birds would have investigated the fishing here.

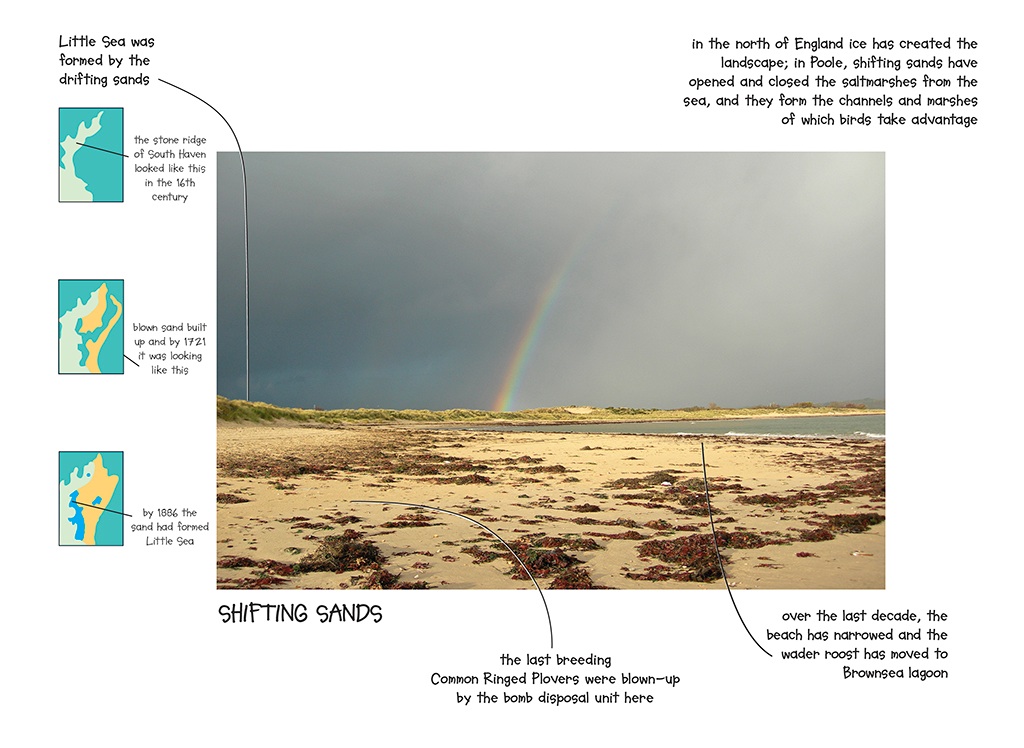

Shell Bay, Studland, Dorset, 25 November 2009 (Nick Hopper). Looking north-west. ‘Shifting sands: God forming Shell Bay on a Saturday.’

Poole’s first written bird record was made by the area’s first birder. He was literally a saint, St Aldhelm (639-709), and he wrote of more familiar birds like Wood Pigeon, Swallow, Nightingale and Chaffinch (Prendergast & Boys 1983). During his lifetime, better weather prevailed again. This was the start of the medieval warm period that lasted until 1250. Summer temperatures rose to around 1-2°C higher than today, bringing back the warmth-loving birds, and in AD 998 we suspect that birds such as Quail, Eagle Owl, Hoopoe and Golden Oriole were in Poole Harbour.

From a bird’s point of view, people weren’t such an issue in the 10th century as there were so few. Poole had a couple of fisherman’s cottages. Wareham had a population of a few hundred tending fields of garlic, with a handful of people at Studland, Ower, Goathorn, Arne and Hamworthy. Brownsea was owned by the church until 1539, and seldom had more than a hermit or two living there. Ravens were common, and referring to the year 1635, Denis Bond wrote in his chronicle “A Raven bred som tym before Christ dyd this yeare in Corfe Castell” (Cooper 2004). The fortress was rendered useless by Parliamentarian explosives in 1646, but Ravens still breed in its ruins today.

Around this time, major geographical changes were unfolding in the Studland area. Longshore drift was shifting sand along the beach and slowly closing the harbour mouth. By 1700, the drifting sand had formed dunes, which managed to cut off the open sea behind Pilot’s Point entirely, isolating Little Sea and making it one of the most recent naturally formed lakes in England.

By 1750, most of Dorset and all of the areas surrounding Poole Harbour were heathland. Only the river valleys and the harbour shores were more fertile. A person living on the edge of Wareham then would be heating their home with peat, while on the edges of the heath the scrubby trees, the heather and gorse had to provide him with fodder, fuel and building materials. This management stopped trees encroaching and kept the gorse in perfect condition. It would have been ideal for the Dartford Warblers, whose population must have peaked around this time.

Poole was built by fishermen and merchants. Their focus was the sea, especially the newly discovered cod fishing at the Grand Banks off Newfoundland, Canada. They built the port and their business by taking salt and other provisions to Newfoundland, where over time many of them settled. Poole had more ships trading with North America than any other English port, and while the men were busy sailing the seas, the birds flourished.

By 1820, the golden age of the Newfoundland trade had ended, prices for cod had halved and bankruptcies and ruin followed. The Napoleonic wars were over, and although smuggling was still profitable, it didn’t pay as well as it had. The weather had become far colder and the men of Poole who had hardly been home for 200 years had to look to Poole Harbour’s natural resources for an income, starting with water birds.