From the minute dawn broke, a constant stream of Song Thrushes flew past us, heading north. Within half an hour, several thousand had flown through. Not high overhead but low and often at eye level, in sizeable flocks of 30 to 50 birds, flying over the bushes and out over the dunes, then circling overhead before heading off north-west, high over Brownsea lagoon towards Poole.

Mo and I were perched up on the dunes behind the National Trust toilets at Studland. It was 16 October 2005, and birder and butterfly man Tom Brereton had co-ordinated a group of birders to count visible migration through Dorset. The idea was for Mo and I to see how many birds flew past in a two-hour period. I used my Telinga parabolic microphone to help make the high-pitched calls more audible, and to separate the short, less obvious Song Thrush calls from the longer, more obvious Redwing sounds. We kept counting for four hours, and by the end had seen 6,205 Song Thrushes and 2,896 Redwings. With 4 Ring Ouzels, 6 Blackbirds and 43 Fieldfares, it was to become one of the best thrush days on record in southern England.

As the thrush passage slowed a little, the first of 3,000 finches started coming through, in groups of 20 to 30, including 927 Linnets, 812 Chaffinches, 452 Siskins and 345 Greenfinches, all in the course of the morning. Accompanying them were eight different Sparrowhawks; adult males, and both young and adult females. A total of 48 Eurasian Jays made their way through the bushes, seemingly nervous to fly over the water, circling up and then returning over our heads, before hesitantly setting off over Brownsea.

Adding variety were two Crossbills, five Bramblings, a Woodlark, 11 Skylarks, two Redpolls, a Bullfinch, 35 Meadow Pipits, 92 White/Pied Wagtails, two Grey Wagtails, 54 Barn Swallows, 12 House Martins, 118 Starlings mixed in with the Redwings, and a record 34 Reed Buntings. The strange thing is that these migrants were all flying north, not the obvious direction for birds heading to the continent, and in some cases Africa.

The Song Thrush count was an excellent record. Some 1,100 passed Durlston on 30 October 1989, which had previously been the largest single day passage recorded either for Dorset or as far as I can tell, for Britain. In the Netherlands, where large numbers of migrating Song Thrushes are seen annually, the largest recorded passage has been over 30,000 in a day. Watching thrushes and other birds migrate in this way is well organised over there, and for several years now, counts from a large number of migration watchpoints have been collated in a database at www.trektellen.nl (Trektellen).

Song Thrush Turdus philomelos, on migration, Texel, Noord-Holland, Netherlands, 29 September 2010 (René Pop)

Recently, this system has been expanded to a number of other European countries including Britain. Some keen migration watchers here have entered their older data. So, looking on this site we can see that in October 2005, watchers from Scotland and northern England recorded very little migration of Song Thrushes. However, in the week leading up to our British record, Dutch coastal watchers saw huge numbers with a peak of over 30,000. By 16 October, Dutch sites were back to reporting them in low numbers.

The Migration Atlas (Wernham et al 2002) sums up ringing data collected by the BTO. Reading their summary on Song Thrushes ringed in autumn in Britain and controlled in spring enables us to make an educated guess that ‘ours’ were from the Nordic countries and had flown in overnight from Holland. So that’s probably where they came from, but where were they going?

Nowhere. At least not for a little while, they had just arrived at their destination. That morning the weather had delayed and concentrated them, and we had witnessed the ensuing spectacle. Ringing records suggest that Song Thrushes are consistent in their habits, and slowly move west across southwest Britain and Ireland during the winter (Alerstam 1990, Wernham et al 2002).

The count of 2,896 Redwings was another record for the harbour, although we know that large numbers pass unseen high overhead during migration. Unlike the Song Thrushes that regularly winter in our area, the Redwings’ destination appears to be a lottery.

Leaving Norway, Sweden and Finland, they decide which direction to fly more or less on take off, depending on the wind. If they find a tail wind that takes them east, they end up wintering around the Black Sea. If it blows them our way they winter in the west of England, Ireland and France and down the Atlantic seaboard as far as Morocco.

Migration from Scandinavia normally starts just after a depression has passed. The Redwings sense that the time has come to move, and tens of thousands lift off from a huge area around 40 minutes after sunset. They call to each other as they climb upward at a rate of 75 m per minute while searching for a good tail wind (CD1-56). In the dark, the individual Redwings listen to each other’s calls and gauge the speed of the birds above and below them, joining them if they are moving faster. This concentrates their numbers, but they don’t fly in dense flocks and can be 50 m apart even on a busy night (Alerstam 1990). Sometimes we can hear these passing birds’ calls as we make our way to the pub, and we dream of seeing them in their thousands, passing overhead the next morning.

CD1-56: Redwing Turdus iliacus Fair Isle, Shetland, Scotland, 18:30, 17 October 2005. A mass exodus of migrants at dusk, on a windy autumn day. Background: European Golden Plover Pluvialis apricaria. 05.027.MR.02400.02

Once on the go, those coming our way travel fast. Recently, birds likely to include Redwings were recorded flying over the Netherlands at 100 km/h by radar. A few nights later, birds were detected arriving directly from Norway at an average speed of 90 km/h (Hans van Gasteren pers comm).

Wind directions vary at different heights above the ground, and by comparing them we can learn something about the bigger picture. Watch a column of smoke rising from a factory chimney and you will see a kink at the point where it reaches the crosswind. If you are watching birds in the morning from a headland on a windy day, try the following method of weather forecasting. Find an exposed spot and stand with your back to the wind. Look up and watch the direction of the clouds. You may be surprised to see them scudding from your left to your right. If this is the case, you need to get under cover as the weather is deteriorating. If on the other hand the clouds are passing from right to left, the weather is improving (Watts 1968).

Watching visible migration or ‘vismig’ started innocently enough when in the summer of 1998 I took Mo out for a romantic dinner and after a few glasses of wine, I asked her if she had ever seen the glory of finch migration. Graciously, with tears of laughter in her eyes, she replied, “No I haven’t. That would be lovely.” I explained how on breezy October days, I had watched the steady passage of flocks of finches and wagtails passing the coast at Durlston. I started to wonder where I could take Mo inside the harbour to see the same.

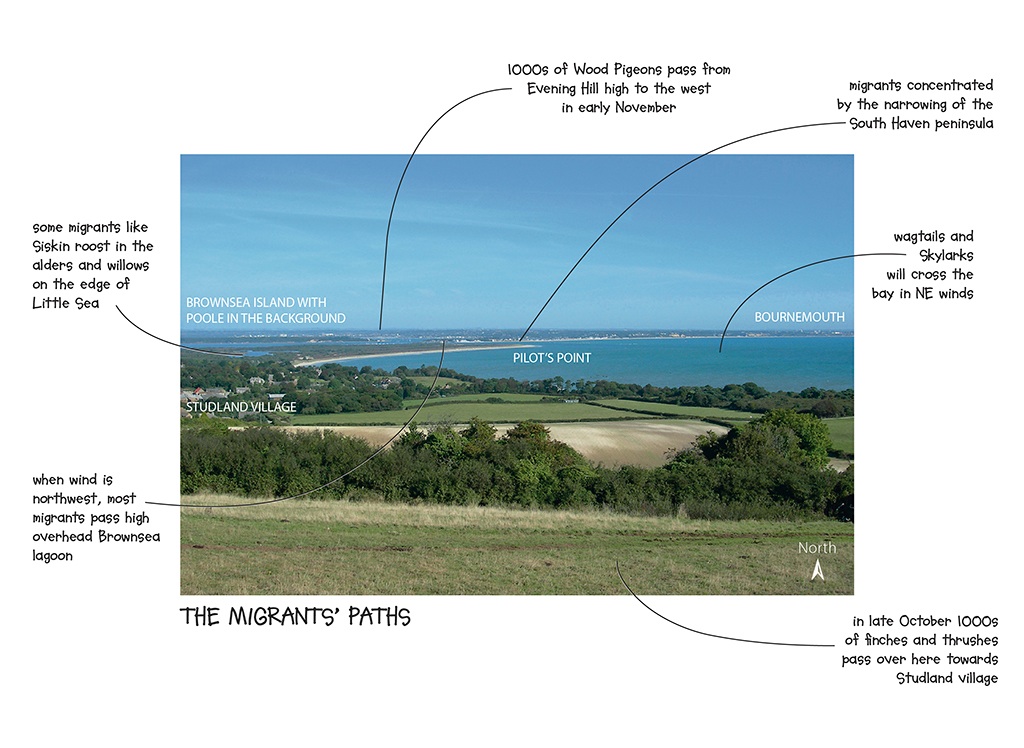

When I got home I took my maps out. I explained earlier about my maps marked up with rarities. Now I drew the potential flight line of finches as they might follow the coast flying into the harbour, having left Durlston and Swanage Bay, and came up with a line that passed across the ridge at the top of Ballard and down to the east of Glebelands, then over Studland village. If I was right, the flight line would pass somewhere around the trig point.

In a northeasterly wind on 4 October 1998, Mo and I went to investigate straight after dawn. There it was, the glory of finch migration, mixed in with the last of the thrushes finding cover after flying through the night. It seemed fantastically busy, with thrushes dropping out of the sky and making their way down into the village: 25 Blackbirds, 22 Redwings, five Mistle Thrushes, three Song Thrushes and thrilling as always, three Ring Ouzels. Then groups of finches were all around us: Chaffinches, a Brambling, Greenfinches, Goldfinches, Siskins and Linnets. After an hour or so, the final tally was over a thousand birds and also included Skylarks, Meadow Pipits, Tree Pipits, Pied Wagtails, a Yellow Wagtail, Sand Martins, House Martins and Barn Swallows. All streaming down the fields towards Poole Bay. Mo thought it was lovely.

Finches are far more predictable than the thrushes. Take Chaffinches for example. Having passed down through Denmark, Germany and Holland every October, at least 30,000 will make landfall on the Dorset coast. In easterlies, some of these birds will fly high and cross the c 180 km from the Low Countries to Norfolk, having flown at around 40 km/h for several hours each morning. But with westerly winds ‘our’ Chaffinches will fly low and continue along the French coast to Cap Gris-Nez or beyond to approach Dorset from the south.

Migrating birds suffer the same problems as a marching army. Napoleon for example, well known for putting his men far ahead of his supply lines, relied on finding local provisions and billets for the men. Having a division of 20,000 men to look after, the quartermasters would have to spread them over a large area (Chandler 1995). Our army of Chaffinches has the same problems, having reached the coast and finding their fat reserves running low, they then make their way inland looking for food and shelter. Some will settle in Dorset for the winter, but there are far more of them than the local area can support, so most have to keep moving on, many continuing northwest to Wales and across the sea to Ireland.

Chaffinches, Goldfinches and other day-migrating birds tend to have less reliable food sources than the night migrants, because of big annual fluctuations in the size of seed crops. Southeast Dorset is unusual among migration sites for its large numbers of Goldfinches, with up to 35,000 passing through Durlston in most Octobers. Unlike the Chaffinches, the Goldfinches are British birds that will winter to the south and west. By migrating during the day, they can find local food and connect with Goldfinches that have been around longer. This way they can follow these birds to a safe roost. The next morning they again follow the more purposeful Goldfinches to rich local feeding sites.

European Goldfinches Carduelis carduelis and other passerines on migration, Ballard Down, Dorset, 12 October 2010 (Nick Hopper)

Shaun’s garden is well stocked each evening with niger seed. Like roast pig is to Napoleon’s old guard, so niger is to Goldfinches. However at Shaun’s there’s no such thing as a free lunch and he catches the visiting Goldfinches, rings them and sets them free. Most of us watching our local garden birds would imagine that they are the same fellows each day. Shaun has caught around 50 birds and hasn’t retrapped any. More food disappears when he is at work during peak visible migration days than quiet ones. Shaun calls it the Napoleon Index.

Large roosts are common for most birds. Staying together through the night reduces predation and as we’ve seen, enables

visitors to get to know the best feeding sites. Two of the species that use communal roosts are great ambassadors for birds. Pied Wagtails in Poole move their winter roosts around, sharing the spectacle among schoolchildren at Poole Grammar School, senior citizens at the nursing home and Christmas shoppers at Falklands Square in the town centre. Even more noticeable are the starling roosts.

In 2010, Pete Miles stood on Poole High School’s playground with his sons, watching 50,000 Starlings. The flock filled the sky, one moment looking like a swarm of bees, the next a shimmer of herring foming a bait ball high over their heads. Splitting into fragments, the swarm streamed over the school buildings, across the railway line and poured into the conifers lining it. As if there were some hidden signal, a blizzard of 10,000 birds vanished, each finding its perch in a split second. The birds immediately started to murmur to each other. “A wonder like that… and us just looking makes you think,” said Pete.

Common Starlings Sturnus vulgaris, Sterte Esplanade, Poole, Dorset, at dusk, 11 January 2011 (Richard Crease/Bournemouth Echo). ‘A starling roost so spectacular it intruded into people’s lives, they could not drive, they brought children to watch… such was the noise that teachers could not teach. People could only stand and stare.’ Starlings migrate into southern England in cold weather from northern Europe. Recorded in CD1-57.

They certainly make a lot of people think, with crowds gathering as they would to watch a firework display. Car drivers, queueing to get out of town in the evening rush hour, are thrilled by the sight of the wheeling flocks. We went there ourselves in early 2011 and recorded the spectacle. Magnus has edited out the worst of the traffic, but otherwise this is just how they sound if you are close enough to the roost when they come in (CD1-57).

CD1-57: Common Starling Sturnus vulgaris Poole High School, Dorset, England, 16:52, 9 January 2011. A flock of around 10,000 starlings coming to roost. At first you can hear a faint whisper of wings and the occasional low call, followed by a much louder fluttering of wings as they land, then a swelling tide of bickering as they compete for the best perches. Background: Common Blackbird Turdus merula and Eurasian Magpie Pica pica. 110109.MC.165200.33

There is one other bird that we see in huge flocks. Wood Pigeons. At Christchurch in late October, migration watchers were getting big numbers of Wood Pigeons. They must, I reasoned, be passing through the harbour too, but where? They didn’t seem to be flying over the harbour mouth. Mo and I started to look across Canford Heath to the north of the conurbation on suitable mornings, and at Corfe Castle. Then we had a verandah built at the top of the house and thought that this would be a great place to monitor pigeon flocks.

Come 1 November 2006, Mo and I were stationed at our new lookout. Just after dawn, a few aimless flocks of Wood Pigeons were milling round over the town. After a while they started to fly a little more purposefully, and we could see them join a much larger flock really high in the sky (around 300 m) over Brownsea. These birds flew a little way west, then turned and headed over the ridge towards the coast. Scanning back at the same height, we found another flock, and another. I had arranged with James and Graham to watch from South Haven, so that we could co-ordinate our efforts. They could see the same heavy passage of Wood Pigeons, but far higher than we normally looked, with a number of large flocks of over a thousand, and some lines of birds stretching across very long distance. James counted about 30,000 in total.

Then at 08:45 a Little Bunting announced itself to James and Graham with its distinctive call as it flew over the harbour entrance. That put paid to the counting of Wood Pigeons at South Haven for the morning, and was something of a shock to Mo and I up in our distant eyrie. We had counted 41,505 Wood Pigeons. Another 14,100 the next day and 6,000 the day after that added up to 61,605 migrating over the three days. Would we have swapped all these Wood Pigeon flocks for one flyover Little Bunting? Of course!

It didn’t put us off though, and in 2007 we were back up on the verandah again, managing 41,200 on 31 October, together with over 1,000 Stock Doves. This smaller species benefits considerably in speed and energy by moving within the Wood Pigeon flocks. Some 900 Jackdaws flying west beneath the ‘Woodies’ may also have been taking advantage of the mass movement in the same way.

The Wood Pigeons did help me solve one final puzzle. Why do so many migrating birds we see on the south coast fly into the wind, often going a different way each day? One particular morning, the morning before Bonfire night, Wood Pigeons were struggling. As is often the case when the nation plans its bonfire parties and little boys are looking forward to fireworks, the weather wasn’t perfect. There was a strong westsouthwest wind and heavy rain showers. You wouldn’t expect to see the Wood Pigeons on such a morning, because they normally move on clear calm days with no cloud. In fact Nick was lying in his bed, exhausted from chasing Firecrests around Studland the day before, so my 08:00 phone call wasn’t really welcome.

“The Wood Pigeons are moving, Nick.”

“Really? In this weather? I’m knackered. Claire has got the day off.” A good excuse that translates as, “I’m not allowed out. Let me know how it’s going.”

20 minutes later I called again, “Hi Nick, I’m watching a flock of a thousand, they really are moving.” I was worried it looked like a record day, and I explained to him that I had a date at 10:00, taking 80 school kids out on the bird boat. I entreated, but it was no use.

Nick was doing a corvid study for this book, so unrelentingly I called again at 08:30. “Jackdaws are moving. I’ve just seen 372. You really must come.” Suspecting he was being tricked out of bed, Nick exploded, “Can you guarantee me Jackdaws?”

No, I couldn’t guarantee the Jackdaws. I wasn’t even sure I could identify them at such a distance. They sneak past looking like Wood Pigeons in bright light, but smaller with a different size and flight. They don’t rise up like the Woodies, but prefer skimming the tops of the trees at Brownsea. So they are hard to do, Nick hardly believed my count. Still, he’d never believe me if I couldn’t get him over here to look. I added my count to Trektellen and Nick called. We apologised to each other, admitting the frustration of trying to be in the right place at the right time, watching the right thing, especially day after day.

That evening, I posted the Wood Pigeon numbers on our local web group, ‘Out and About’. I read of sites further west getting flocks of 1,000 Wood Pigeons, and the descriptions were like my own. “Long lines of birds stretching hundreds of metres.” The Woodies seemed to have gone as far west as Dawlish Warren, 103 km as the Wood Pigeon flies. I started thinking about that same old question: why do so many of the migrating birds we see in the harbour fly into the wind no matter which direction it takes them? The Napoleon theory doesn’t really help with Wood Pigeons.

At first I imagined that all these Wood Pigeons were continental birds coming from Holland, until Magnus explained that Wood Pigeons don’t migrate along the coast of Holland or Belgium but follow the border with Germany. I then pursued the idea that they were Norwegian birds coming down through Scotland, where the British co-ordinator of Trektellen, Clive McKay, had been counting many passing along the east coast. A phone conversation with him soon corrected that. The birds Clive sees are doing local movements, and none of the traditional Scottish migrant islands or North Sea oilrigs see any Wood Pigeon flocks in the autumn.

By a process of elimination we can deduce that they must be British birds moving south to join huge numbers from elsewhere, to winter in Spanish oak forests. Awkwardly, however, there are so few European recoveries of British-ringed birds that we can’t prove this theory.

Let’s assume that they roost in the millions of pines throughout the New Forest, then in early November when the temperatures drop about half an hour after dawn, they rise up and up, clearly wanting to migrate. Flying so high in the sky first thing in the morning, on a good clear day they should be able to see across the English Channel. More importantly, this test flight allows them to check the direction of the cross winds for something suitable.

On 7 November 2010, a local fishermen saw large pigeon flocks flying over his boat. Hardly surprising, because on that morning Mo and I hit a huge jackpot, counting 161,257 woodies moving across Poole Harbour in just a few hours. (I should mention that the numbers were counted more carefully at the beginning and end of the count, hence the 257, while they were estimated with practiced accuracy when in full flow.)

Suddenly it all came together when I remembered my last trip to Scilly, flying in a tiny plane out of Newquay. It was a squally day, and to make the ride as comfortable as possible the pilot was navigating around the obvious squalls. I realised that the Wood Pigeons on this day were doing something similar. That’s what they were looking for, the right spot to cross the channel. It’s not the distance across water that matters most. It’s the wind speed and direction, and the lack of rain. When truly migrating, the birds will go like the clappers, but they have to find the right spot in the weather system to cross water or risk drowning.

The principle that enables you to stand with the wind to your back, determining whether the weather is going to deteriorate or improve by watching the overhead clouds, works because the wind blows out of high pressure, and in towards low pressure. Perhaps it would be more appropriate to say it slips off the high pressure.

I realised then that all migrating land birds use this strategy when crossing the channel from the south of England during unpredictable weather, and that this was another reason why we often saw birds flying into the wind. Whether it intends to cross or forage locally, any finch, swallow, lark or in this case Wood Pigeon flying into the wind will always be flying towards better weather. Those that choose a different course may well perish.

Not even this theory got Nick out of bed. At that time he still didn’t approve of too much focus on migrating common birds. He preferred rarities.