Killian Mullarney

Text by Magnus Robb

Imagine the thrill of being alone at dusk on a tiny islet, certain that you are about to be blown away in a blizzard of White-faced Storm Petrels Pelagodroma marina. Sitting watching the sun go down over the north coast of the Cape Verdean island of Boavista on 1 March 2004, I could hardly wait for the night to begin. Soon the little holes excavated in the sand, all over the islet, would be bustling with activity. I turned seaward and watched an Osprey Pandion haliaetus settling down to roost on a distant rock. Brown Boobies Sula leucogaster emerged above the distant horizon at intervals, then disappeared again behind crests of the waves. Beyond them, the nearest land was Dakar in Senegal, some 580 km to the east.

After the great volcano of Fogo, where I had recorded Fea’s Petrels Pterodroma feae a few days before, the almost flat island of Boavista, with its sand dunes and palm-lined oases, seemed like a lost fragment of the Sahara. I had wasted no time in trying to visit Ilhéu dos Pássaros, because the moon was already past first quarter. As usual, the people of this friendly archipelago helped me to get something organised. The owner’s son at Residencial “Bom Sossego”, where I was staying, drove me to the village of Norte to assist in organising a boat ride. Successful negotiations in the Cape Verde Islands often involve beverages, and always take time. After a while, being unable to follow the nuances of Cape Verde Creole, I sneaked off to record the song of a male Iago Sparrow Passer iagoensis, endemic to the Cape Verde Islands, chirping from the eaves of the roof. I should have known better. Before long half the village was watching me at work. The commotion helped to round off the negotiations and I shook hands and paid Pepe, the tall, phlegmatic owner of the boat. It was to be skippered by Francisco, a bright, enthusiastic young fisherman, who brought me down to the shore.

In a hybrid of English, accidental Spanish and something resembling Portuguese, I tried to explain the itinerary I had in mind. Besides Ilhéu dos Pássaros just 800 m offshore, I wanted to visit the more distant Ilhéu Baluarte for Brown Booby and, just maybe, a Magnificent Frigatebird Fregata magnificens. I asked if we could go to Baluarte first, then return to Pássaros to spend the night there. When Francisco insisted that Pássaros, despite its name, was birdless, I thought it prudent to have a quick look there on the way out.

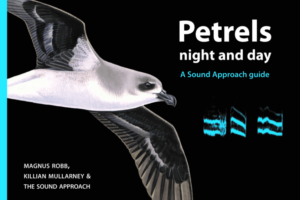

White-faced Storm Petrel Pelagodroma marina, adult arriving in its breeding colony at night, Branco, Cape Verde Islands, 14 February 2004 (Arnoud B van den Berg)

After we loaded my gear and launched the 4 m long wooden dinghy, Francisco seemed to be having great trouble getting the little outboard motor to start. Suddenly, he dived into the water and swam back ashore, returning with a short length of tubing in his mouth. Once he had shaken out the sea water and inserted it somewhere into the motor, he pulled hard at a cord to get the motor spinning and off we went. In no time, Francisco carefully manoeuvred us into the shallows surrounding Ilhéu dos Pássaros. Wading to dry land, I discovered that the islet was round; a flat, sandy central part just 80 m in diameter was surrounded by a narrow, rocky rim. One glance at the surface confirmed that, underneath a thin layer of ankle-high, salt-tolerant vegetation, the sand was riddled with storm petrel burrows.

White-faced Storm Petrel Pelagodroma marina, ecstatic feeding dance, near the Selvagens, 26 June 2006 (Killian Mullarney)

When I started wading back out to join Francisco and head off to Ilhéu dos Baluarte, he signaled me to wait. Vigorous sweeping movements of his right arm told me the motor was playing up again. I stood for a few minutes, up to my knees in the water, while he drifted further out. Finally, the boat spun around and Francisco was off like a shot, heading back towards Boavista without me, but carrying all my recording gear. He made some gesture I failed to understand. The optimist in me hoped that he was just going back to get another mouthful of tubing, or perhaps even a different outboard motor. I politely asked the pessimist in me not to think at all. For distraction, I had another quick look at the petrel burrows, finding a couple of fresh feathers, a desiccated storm petrel corpse, and some fresh white droppings on the sand. To my great relief, Francisco reappeared again fairly quickly. Proceeding to Baluarte while I was already in a perfect location seemed foolish, so I offloaded my gear and asked him if we could postpone that until the morning. And, by the way, would he mind bringing two outboard motors the next time, just in case?

Half a moon earlier, in the company of Arnoud van den Berg, I had visited my first White-faced Storm Petrel colony on Branco, the islet west of Raso. In the light of our torches, we saw them sailing up the sandy beach, wings outstretched in the stiff wind, bouncing off the sand by using both feet as they do at sea. We knew that White-faced were silent in flight, but the wind was so strong we didn’t hear a single call from the ground either. With very little vegetation for support, the Branco colony is particularly fragile. For me, the experience was marred by the discovery that a burrow could collapse where you were not even aware there was one. On Ilhéu dos Pássaros, the situation was much better for both petrels and recordist. There were enough burrows near the rocky rim that I could get sufficiently close to listen while keeping my weight off the sand.

For the first hour or so after dark, it seemed as if my bad luck was about to be repeated, but not for a lack of storm petrels. Every now and then, when I switched on my light for a moment, I could see that there were many flying over the islet. Once or twice a wingtip brushed against my face. Sometimes I noticed a petrel landing nearby, and scurrying down into a burrow. When this happened close enough to solid rock, I put my ear to the ground, but in vain. All around me were storm petrels, and yet I was unable to hear a single call. Eventually, I struck on the idea of scanning the ground with my parabolic microphone, and this saved the night. Storm petrels were calling in their burrows all right, but muffled by the sand and masked by the surf, I had simply missed them. In CD2-07 you can hear how they sounded from about a metre, with a non-directional microphone placed on the ground between several burrows. Their calls really are weak.

CD2-07: White-faced Storm Petrel Pelagodroma marina Ilhéu dos Pássaros, Boavista, Cape Verde Islands, 1 March 2004. Calls of three individuals, recorded from outside their burrows. Background: surf less than 20 m away. 04.009.MR.02810.11

All the White-faced Storm Petrels I have ever heard in the field, and in most published recordings, produced variations on essentially the same diagnostic call, which I call their ‘rhythmic call’. Most notes are a kind of hoot or bark, not dissimilar to the sound of Bulwer’s Petrel Bulweria bulwerii, which has a completely different speed and rhythm. The exact timbre varies between individuals and according to the acoustic surroundings. A rhythmic call series consists of several three-second phrases, each repeating a simple, consistent pattern. Listen to a clearer recording of the rhythmic call, this time recorded when I placed my microphone just inside the entrance to a burrow. The occupant seemed unperturbed, and gave a couple more series of typical rhythmic calls (CD2-08).

CD1-08: White-faced Storm Petrel Pelagodroma marina Ilhéu dos Pássaros, Boavista, Cape Verde Islands, 1 March 2004. A series of rhythmic calls recorded at very close range: a ‘bird’s ear’ perspective. 04.009.MR.00000.00

The level of calling in the colony was pretty low, and the petrels I was recording soon seemed to lose interest. After a while, I discovered a way to keep them talking. From outside the burrow, I imitated their calls as best as I could. The response was immediate, and sometimes a White-faced Storm Petrel came right up to the microphones to deliver it. In CD2-09 you hear my imitation first, muffled because the microphones were slightly inside the burrow entrance. Then you hear the response of the storm petrel, loud and ‘in your face’ at the start, but more muffled the next two times as it moves further down its tunnel in the sand.

CD2-09: White-faced Storm Petrel Pelagodroma marina Ilhéu dos Pássaros, Boavista, Cape Verde Islands, 1 March 2004. A little conversation with a storm petrel, recorded from just inside a burrow entrance; my imitations of rhythmic calls sound muffled and distant, and are followed by a much closer response from the occupant of the burrow. Different individual from CD2-08. 04.008.MR.13500.00

The rhythmic calls I recorded varied in timbre, speed of delivery, and the length of the hoots. These variations may be evidence of strong individual variation, or there could be differences between the sexes (CD2-10). All we know is that when both members of one pair in a burrow on Selvagem Grande had been sexed tentatively, based on measurements, the female’s calls were delivered more slowly. Both the notes and the gaps between them were shorter in the male, which had a slightly higher fundamental frequency (James 1984b). It would be unwise to draw too many conclusions from just one pair, but differences in timing clearly deserve further investigation. In the closely related Wilson’s Storm Petrel Oceanites oceanicus, these differences are largely the reverse. In females, the ‘grating call’ is clearer in tone, higher pitched and given at a faster tempo than in males (Bretagnolle 1989).

White-faced Storm Petrel Pelagodroma marina Ilhéu dos Pássaros, Boavista, Cape Verde Islands, 1 March 2004. Rhythmic calls of another individual. 04.008.MR.14832.11

White-faced Storm Petrels whose calls were prompted by my imitations were clearly on the defensive. Their vigorous response, especially the loud notes at the start, sounded like a show of strength in the face of a challenger. In the Cape Verde Islands, laying takes place from late January to March (Mougin et al 1992), so at the time of my visit, most breeders probably had eggs. The main period of courtship had already passed when I made these recordings, and on this half-moonlit night, the number of non-breeders would not have been particularly high. It would be interesting to record breeders closer to the start of the season. Perhaps calls vary depending on whether a partner or a rival is being addressed. I only had one night on Ilhéu dos Pássaros and little opportunity to advance our understanding. Nevertheless, I was delighted at least to have made recordings of these diagnostic calls.

Francisco turned up promptly at 09:00, and this time his boss was with him. Much to my relief, there was a reserve motor lying in the boat, although its condition looked even worse than the one that was in use. I sat in the bow, and it soon became clear that my clothes were going to get very wet. So I improvised a poncho for myself, made from a black bin-liner. The crew’s more ingenious solution was to wear hardly anything at all. Ilhéu de Baluarte turned out to be at least twice the size of Ilhéu dos Pássaros, elongated and rocky, and home to a healthy population of Brown Boobies. Francisco moved the boat in as close as he dared, but the waves made it impossible to get within jumping range of the rocks. Trusting blindly in my waterproof kayaking bag, I jumped into the sea and swam ashore with my recording gear under my arm.

Boatmen Francisco (left) and Pepe (right), Ilhéu Baluarte, Cape Verde Islands, 2 March 2004 (Magnus Robb)

A little later, the boat was somehow tied up to the island after all. While Francisco and Pepe relaxed in the sun, I recorded the croaks and hisses of boobies, including a downy white young as large as an adult. They seemed to be the only birds breeding on the islet. One adult was so tame that I was able to photograph it from just a metre or so, brooding on its nest. The rocky surface of Ilhéu de Baluarte, which had very few crevices, seemed an unlikely place for breeding petrels. There was no sand, so there were certainly no White-faced Storm Petrels. Just as we were about to leave, something dark eclipsed the sun. A huge male Magnificent Frigatebird, one of only about five in the eastern Atlantic, passed less than 10 m above me. My heart stood still as it flew once around the islet, showing off the loose, bright red skin on its throat, then it headed back out to sea as silently as it had arrived.

Pushing the boat off the rocks, we drifted gently while Francisco wrestled with the motor. It barely chugged into action, so we were in for a long ride back. Following some discussion I couldn’t follow, the scruffy old outboard was taken off and replaced with the even scruffier reserve one. Francisco did his familiar arm exercises, but there wasn’t even a splutter. By now we were drifting out of the lee of the islet and into choppier waters.

While Francisco was doing his best, Pepe’s voice took on a whining and accusing tone. The first motor went back on, and the cord-pulling resumed at a faster pace. The longer we drifted, the more heated the language became, and eventually I realised why. Between us and the mainland was a long line of breaking waves. A narrow reef several hundred metres long ran out diagonally from the white sands of Boavista, and the north-easterly wind was pushing us right towards it.

The fishermen began to sound desperate. When we were about 30 m off the reef, they both jumped into the sea. Holding onto the boat, they started kicking as hard as they could, to push the boat away from the reef. Despite the futility of it, I jumped in and joined them, but no sooner had I done so than we all climbed back in. It was clear by now that we were going to hit the reef, which was only a few metres away. Frantically, they started lashing both the outboard motors onto the inside of the boat. If it was going to tip over, they didn’t want to end up without any motor at all. Likewise, I tried to attach the rucksack containing my gear and my White-faced Storm Petrel recordings onto something solid, but it was too late. Francisco and Pepe had already jumped over the side again, and were hanging onto either side. “Salto!”, cried Francisco, so I jumped in and hung onto the gunwale. Francisco clenched his fist and wished me “força!”.

Two seconds of foam and confusion, and we found ourselves on the calm side of the boiling reef. Everyone was unhurt, but the boat was half full of water. By hanging on, we probably stabilised it enough to prevent it turning over completely. At the point where we met the reef, the rocks were below the surface. A mighty wave lifted us right over them: boat, three bodies and six dangling legs. Now we climbed back in, and started bailing out with a sawn-off plastic water tub. 15 minutes later, we drifted onto the sandy shores of Boavista, a kilometre further on. If the wind had been blowing the other way, we might have washed up in Mauritania, goodness knows how many weeks later.

White-faced Storm Petrel Pelagodroma marina, near the Selvagens, 26 June 2006 (Killian Mullarney)

The colony on Selvagem Pequena is much larger than the one on Ilhéu dos Pássaros, and has been estimated at 25 000 pairs (Oliveira 1999). The surface is completely riddled with burrows. White-faced Storm Petrel is by far the most numerous species on the sandy and almost entirely flat island. The roots of Icicle plants Mesembryanthemum cristallinum and M nodiflorum help to stabilise the burrows, but cannot protect them from the weight of human feet (Zino & Biscoito 1994). Since 1993, the island has been wardened each summer from May until October. Before that, visiting fishermen and passing yachtsmen used to trample many nests. There is a well-marked path so that infrequent visitors, who must have permission from the Parque Natural da Madeira, can reach the warden’s hut without mishap.

Burrows of White-faced Storm Petrels Pelagodroma marina, Selvagem Pequena, Selvagens, 26 June 2006 (Luis Dias)

After my experiences on Ilhéu dos Pássaros, I knew what sound to listen out for, and I was confident that I would hear calls of White-faced Storm Petrels in their burrows along the path. Countless individuals were flitting in and out, but they all seemed to be mute. To my dismay, imitating their calls near burrow entrances had no effect, except to make me feel a bit of a twit. Eventually, later in the night, I did hear rhythmic calls of a single spontaneously calling individual, underneath an Icicle plant. The calling stopped before I was ready to record it, so to elicit the calls in CD2-11, I used an imitation.

Rhythmic calling, it seems, is rare this late in the breeding season. Luis Dias, our naturalist skipper, heard no White-faced Storm Petrel calling from burrows when he visited the Selvagens a year previously, although one that crashed into him gave rhythmic calls from his lap. Then as now the Ventura do Mar was visiting the Selvagens towards the end of the breeding season. The Selvagens colonies are attended from December, with most birds probably arriving to clean their burrows in January. Freshly laid eggs have been found from 17 March to 1 June, with a mean laying date of 8 April. Hatching takes place anything from 46 to 60 days later, so by the time of our visit in late June, most burrows would have contained young (Campos & Granadeiro 1999). If they did, we couldn’t hear them, though their weak calls may have been muffled by the warren of tunnels.

CD2-11: White-faced Storm Petrel Pelagodroma marina Selvagem Pequena, Sevagens, 00:50, 26 June 2006. Rhythmic calls: two series that were prompted by human imitations, which have been edited out. Microphones placed very close to a burrow entrance. 060627.MR.05050a.10 & 060627.MR.05050b.10

White-faced Storm Petrel is the only northern representative of a predominantly southern clade. This suggests a parallel with the Northern Fulmar Fulmarus glacialis, but White-faced still breeds in the southern oceans as well. Its closest relatives include Wilson’s Storm Petrel and the recently rediscovered New Zealand Storm Petrel O maorianus, which went missing for more than a century (Saville et al 2003). The southern storm petrels or Oceanitinae differ from the northern Hydrobatinae in having longer legs and shorter wings (Warham 1996). There are vocal differences too. Perhaps the most striking is that southerners lack the monotonously repeated purring calls that are such a characteristic sound of storm petrel colonies in the Northern Hemisphere. In addition, the Oceanitinae call mainly on the ground or in their burrows, whereas most Hydrobatinae are highly vocal in flight. Various lines of evidence, including mtDNA (Nunn & Stanley 1998), indicate that these two groups are only distantly related.

White-faced Storm Petrels from the North Atlantic were originally described as subspecies hypoleuca, the type speci-men of which was obtained at Tenerife, Canary Islands, around 1841. They differ from southern hemisphere White-faced Storm Petrels, especially higher latitude populations from New Zealand and Tristan da Cunha, in having a longer bill and tarsus and a shorter tail (Murphy & Irving 1951). Bourne (1953) further separated Cape Verde birds as ‘eadesi’, based on more white in the forehead and a more striking head pattern. After studying more specimens, he was more circumspect (Warham 1958), and Hazevoet (1995) found ‘eadesi’ and all five other ‘subspecies’ too poorly defined for recognition as valid taxa.

White-faced Storm Petrel Pelagodroma marina: known North Atlantic breeding distribution (red dots).

Recording locations indicated by arrows (north to south):

Selvagem Pequena, Selvagens;

Ilhéu dos Pássaros, Boavista, Cape Verde Islands.

I was curious to know whether sounds of White-faced Storm Petrels on the Selvagens would be different from the ones I had recorded in the Cape Verde Islands. But rhythmic calls of the two populations appear to be very similar. Recordings from Selvagem Grande, made by Alec Zino in June 1969, also contain rhythmic calls not obviously different from what I heard in the Cape Verde Islands (Palmér & Boswell 1973). While larger samples from each population might shed more light, on present knowledge there appear to be no vocal differences striking enough to strengthen the case for separating ‘eadesi’ and ‘hypoleuca’ as meaningful taxa.

One further North Atlantic population was recently discovered in the Canary Islands (Martín et al 1989). There are colonies on the islets of Allegranza and Montaña Clara off the northern tip of Lanzarote, and their combined population is estimated a no more than 70-80 pairs (Rodríguez et al 2003). Calls from Montaña Clara recorded by José Manuel Moreno on 6 April 1996 are quite different from the rhythmic calls I have heard in the field. At intervals of three to six seconds, there are identical hoots of descending pitch. I suspect this is a call-type shared by all populations of White-faced Storm Petrel, but only used early in the breeding season. Moreno made the recording on a date when White-faced on the nearby Selvagens have not yet laid, so these descending hoots could be associated with pair formation. This idea is supported by his observations of behaviour on Montaña Clara: “from nightfall, they arrive at the colony very silently, like bats; some enter their burrows and immediately start giving the cúu for a long period of time, while other individuals continue fluttering over the colony, attempting to localise the sounds being emitted”. In Wilson’s Storm Petrel, there are also two main call types (Bretagnolle 1989). One, the ‘grating call’ given by both males and females, appears to be equivalent to White-faced’s rhythmic call. ‘Chatter calls’, given only by males on the ground, are thought to be a male sexual advertising call, their function being to attract females to a calling male who owns a burrow. The repeated cúu hoots of White-faced are probably equivalent to chatter calls of Wilson’s.

White-faced Storm Petrels face a bizarre array of predators as they attempt to complete the breeding cycle. On the eastern Canarian islets, bones have been found in pellets of Slender-billed Barn Owls Tyto alba gracilirostris, and a more surprising enemy is the Canarian Shrew Crocidura canariensis, which preys heavily on nestlings (Rodríguez et al 2003). On Ilhéus do Rhombo, Cape Verde Islands, a ghost crab Ocypode ippeus preys mainly on the flesh of White-faced, ambushed as they enter their burrows at night (Murphy 1924). Elsewhere in the Cape Verde Islands, the endemic Giant Skink Macroscincus coctei, a lizard up to 65 cm long, almost certainly ate White-faced on Branco, until it became extinct about a century ago (Hazevoet 1995). On Selvagem Grande, introduced House Mice Mus musculus are a menace, mainly because they eat unattended eggs (Campos & Granadeiro 1999).

Luckily, introduced mammals never reached Selvagem Pequena, where the White-faced Storm Petrels have few predators to worry about. Only a small garrison of Yellow-legged Gulls Larus michahellis awaits their arrival. The night we visited the island, the storm petrels could fly freely, safe in the darkness of new moon. Attendance was high, probably including a good number of non-breeders. I listened to the whisper of wings passing within a few metres of my head. None of the storm petrels called, but with a little help from my imagination, I could follow their trajectories in the dark.