Killian Mullarney

Text by Magnus Robb.

St Kilda, a remote archipelago beyond the Outer Hebrides in Scotland, is home to a million seabirds. In the daytime, hordes of Northern Gannets Morus bassanus and Atlantic Puffins Fratercula arctica fill the skies. At night, St Kilda is the only place in the British Isles where four species of petrel can be heard calling together in large numbers. Insomniac Northern Fulmars Fulmarus glacialis cackle on their ledges, while crooning Manx Shearwaters Puffinus puffinus and chattering Leach’s Storm Petrels Oceanodroma leucorhoa flutter about in the dark, almost drowning out the sound of British Storm Petrels Hydrobates pelagicus purring quietly in their burrows.

Not long ago, my father asked me if I would like to join him on an expedition to St Kilda, to which the answer was, naturally, “yes”. I was interested in seeing the place where my parents had met, and the petrel colony they had told me about as a child. We travelled to St Kilda on a converted Norwegian rescue ship called the Hjalmar Bjørge, together with my father’s second wife Valerie, and Peter Nuyten, a friend and fellow sound recordist from the Netherlands. Peter and I landed on the main island of Hirta in the late evening, then wound our way up from the village just as it was beginning to get dark. An austere, vagrant Snowy Owl Bubo scandiacus watched us from a cairn, before disappearing into the gloom. On the brow of the hill, a pair of Great Skuas Stercorarius skua mobbed us half-heartedly. We started the difficult descent to Carn Mór, the steep boulder-field on the western slopes of the island, just as the first Manx Shearwater called. Small parties of half-wild Soay Sheep sneezed in alarm when they saw us, and scampered out of sight.

A couple of hours later, the night was overcast and the moon obscured. I could just make out the steep slope covered in huge, eroded boulders stretching down to the sea below. At the top there was a strip of grass, just below the highest section of cliff. I placed my microphones on the snout of a large, bear-shaped rock, where they could pick up the ambience from all sides. When the concert reached its climax about 01:25 in the morning, numerous Manx Shearwaters were hurtling past at breakneck speed. Their performance sounded all the more exotic, as Leach’s Storm Petrels were chattering and flitting about in their midst (CD1-43).

CD1-43: Manx Shearwater Puffinus puffinus Hirta, St Kilda, Western Isles, Scotland, 01:25, 24 July 2007. Calls of males and females in flight, in a colony of some 4500 pairs. Most of the callers in the recording are presumed non-breeders. Background: Leach’s Storm Petrel Oceanodroma leucorhoa. 070724.MR.012507.00

From the middle of the breeding season onwards, Manx Shearwater colonies are visited by hordes of adolescents. They start returning at about two years of age, and attendance increases with age. Breeding adults, usually about six years or older, arrive as early as February. They spend the first part of the season re-establishing the pair bond and spring-cleaning their burrows. Five-year olds may arrive soon after the adults and stay for most of the season, occupying a burrow and vocalising with their partners, but not actually breeding. Two-year olds may only visit during the new moon periods in June and July, roughly the latter part of incubation and the time when small chicks are being fed. These were important discoveries arising from a 12-year ringing study by Ronald Lockley (1942) on the Welsh island of Skokholm.

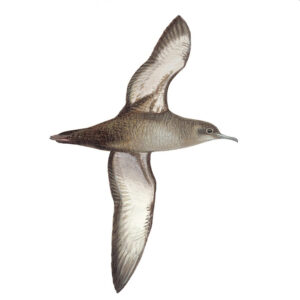

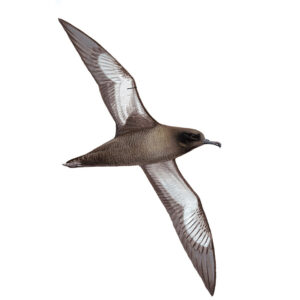

Manx Shearwater Puffinus puffinus, Carnsore Point, Wexford, Ireland, 6 September 2007 (Killian Mullarney)

A wide range of call variation can be heard in Manx Shearwater colonies, and you can hear plenty in CD1-43. Pitch and timbre vary from deep and coarse-sounding to high and crooning. Some callers seem more hurried than others. The rate of delivery varies from bird to bird. Michael Brooke (1978), the first scientist to study Manx calls with sonagrams, showed that individuals could be recognised night after night by their unique voiceprints. Individually recognisable signals explain much of the variation heard in Manx sounds, but there is much more to it than this.

To investigate call variation further, Brooke recorded calling Manx Shearwaters in their burrows during incubation, when they were likely to be alone, stimulating them to call by playing calls of other Manx. Then he took them out and identified the individuals. Their sex had been determined at the very start of incubation, when sexing is easiest. The calls of Manx he sexed as males contained clear exhaled notes with well-defined harmonics. Female exhaled notes generally lacked these clear sounds and had only harsh ones, especially when given at full volume. This was the first time anyone had proven sex differences in shearwater calls, so the discovery was an exciting one. Later research by James (1985a) showed that female calls are shorter than male calls in Manx, as in Barolo Shearwater P baroli and Boyd’s Shearwater P boydi. Not only the call as a whole but also the individual notes and the gap between one call and the next tend to be shorter in females, so the delivery of a typical series of three to five calls tends to sound subtly faster. Listen to CD1-44 for a series of male calls and CD1-45 for an example of a female.

Carn Mór boulder field, an important breeding colony of Manx Shearwater Puffinus puffinus and Leach’s Storm Petrel Oceanodroma leucorhoa, St Kilda, Western Isles, Scotland, 22 July 2007 (Peter Nuyten). CD1-43 and CD1-44 were recorded immediately below the high pinnacle in the centre of the photo.

CD1-44: Manx Shearwater Puffinus puffinus Hirta, St Kilda, Western Isles, Scotland, 01:36, 24 July 2007. A male calling in flight as he flies past at very close range, almost touching the microphones with his wings. Background: Leach’s Storm Petrels Oceanodroma leucorhoa. 070724.MR.013610.00

CD1-45: Manx Shearwater Puffinus puffinus Skellig Michael, Kerry, Ireland, 00:39, 26 August 2006. A female calling in flight as she flies past. Background: British Storm Petrels Hydrobates pelagicus. 060826.MR.03939.20

The discovery that Manx Shearwaters could be sexed in the field just by listening made it much easier to understand their courtship behaviour. This is what Paul James was studying on Skomer, Wales, when he discovered his Barolo Shearwater. His three-year study (James 1985b) confirmed that females are attracted to the voices of males and vice versa. Unpaired males find a burrow and advertise it by calling. Most of their calling is from the ground. Sometimes males call from the air too, but only if they are burrow owners. Unpaired females call mainly from the air, responding to and perhaps provoking male burrow owners, whether they are at home or in the air. By fitting small luminescent markers to the tails of sexed individuals, James was able to follow them with night vision optics. Burrow owners would call from their burrows or from the surface, then take off and call in flight for a few minutes. Interestingly, marked male burrow owners spent only 10.7% of their flight time calling, which suggests that listening was also very important to them. They were also very inquisitive about their neighbours, and when they left their own burrow, many would visit others nearby, even if they were already mated. By trapping Manx flying over the colony, James discovered that there were far more males in the air than their calls suggested. He reasoned that the silent males were immatures that had not yet secured a burrow, listening and assessing their chances in various parts of the colony.

Anne Storey (1984), working in the only North American colony on New Lawn Island, Newfoundland, Canada, tried to work out why male and female Manx Shearwaters differ vocally. She suggested that the greater variability of male calls in frequency, rhythm and their pattern of loudness made them more conspicuous, allowing females to find unpaired males and their burrows more easily. More conspicuous calls also mean greater predation risk, but males can afford this because they do most of their calling from the safety of a burrow. Interestingly, female Manx are able to recognise the voice of their mate, but males are not (Brooke 1978). This may be partly due to the individual distinctiveness of male calls, but female birds appear to be more discerning listeners generally.

Manx Shearwater Puffinus puffinus, Carnsore Point, Wexford, Ireland, 6 September 2007 (Killian Mullarney)

The first time I ever heard a Manx Shearwater was in humid laurel forest – laurisilva – on La Palma in the Canary Islands, on 11 April 2001. Los Tiles biosphere reserve is best known for its numerous Bolle’s Pigeons Columba bollii and Laurel Pigeons C junoniae, but in Moreno’s sound guide to Canary Islands birds (2000), I learned that Manx had been found breeding there too. Nesting in the Canary Islands was only confirmed in 1987 (Martín et al 1989), and Manx breed a month or two earlier there than they do further north. In Los Tiles reserve, they can be heard in the Barranco del Agua, a gorge about 5 km from the sea. This happens to be one of the best spots for recording the endemic pigeons, so I set off with my recording gear in the late afternoon, hoping to record pigeons before the shearwaters arrived.

Laurisilva is a type of lush subtropical forest that used to be widespread throughout the Mediterranean basin before the Ice Ages, but is now confined to the Atlantic archipelagos of the Azores, Madeira and the Canary Islands. It grows best on slopes that face into the prevailing wind, and in Macaronesia this usually confines it to north and north-eastern parts of the islands. Moisture easily condenses when trade winds hit the mountainsides, and as a result the forests on the windward side are humid and often misty. The most characteristic trees are evergreens, including laurels (Laurus, Ocotea, Persea and Apollonia), a holly Ilex perado, and a kind of heath the size of a small tree Erica arborea. Many inhabitants of the laurisilva, both plants and animals, are endemic, specially adapted to this unique habitat. La Palma even has it own blue tit Cyanistes palmensis, which occurs nowhere else in the world.

Breeding habitat of Manx Shearwater Puffinus puffinus, Los Tiles, La Palma, Canary Islands, 12 March 2006 (Jacob Gonzáles-Solís). CD1-46 was recorded near the far end of this gorge.

As I followed the path up the gorge at Los Tiles, I had barely the foggiest idea where I was going. The habitat looked great for laurel pigeons, but I could hardly imagine Manx Shearwaters breeding here. The trail started through a long, damp and very dark stone tunnel. Then it wound along the side of the wooded gorge, on slopes so steep that I could only record from the path. Canary Islands Chiffchaffs Phylloscopus canariensis and Palma Chaffinches Fringilla coelebs palmae were everywhere. Sometimes I stood in the shade of a Tree Heath, where I was able to record the song of Palma Kinglets Regulus teneriffae ellenthalerae. The languid song of the Laurel Pigeons seemed perfectly attuned to the primordial setting, long notes becoming longer still in the damp acoustics of the gorge.

A tix, tix, tix chorus of Common Blackbirds Turdus merula meant dusk was imminent, and it was time for me to head on up the winding path. I proceded another kilometre up the darkening gorge, further and further from the sea. Eventually, under the wooded ridge on the opposite side of the gorg

As I followed the path up the gorge at Los Tiles, I had barely the foggiest idea where I was going. The habitat looked great for laurel pigeons, but I could hardly imagine Manx Shearwaters breeding here. The trail started through a long, damp and very dark stone tunnel. Then it wound along the side of the wooded gorge, on slopes so steep that I could only record from the path. Canary Islands Chiffchaffs Phylloscopus canariensis and Palma Chaffinches Fringilla coelebs palmae were everywhere. Sometimes I stood in the shade of a Tree Heath, where I was able to record the song of Palma Kinglets Regulus teneriffae ellenthalerae. The languid song of the Laurel Pigeons seemed perfectly attuned to the primordial setting, long notes becoming longer still in the damp acoustics of the gorge.

A tix, tix, tix chorus of Common Blackbirds Turdus merula meant dusk was imminent, and it was time for me to head on up the winding path. I proceded another kilometre up the darkening gorge, further and further from the sea. Eventually, under the wooded ridge on the opposite side of the gorge, I could just make out a tiny bare crag.

Nearly two hours after sunset, the fantastic sound of Manx Shearwater calls echoed through the forested gorge. There were just two birds calling, and the colony appeared to be very small. In CD1-46 you can trace their comings and goings by changes in loudness, the calls sometimes fading as one flies round the back of the ridge. The sound of small stones falling nearby ricochets in the gloom, and when a larger boulder falls in the distance, a deep rumble marks its descent into the gorge.

e, I could just make out a tiny bare crag.

Nearly two hours after sunset, the fantastic sound of Manx Shearwater calls echoed through the forested gorge. There were just two birds calling, and the colony appeared to be very small. In CD1-46 you can trace their comings and goings by changes in loudness, the calls sometimes fading as one flies round the back of the ridge. The sound of small stones falling nearby ricochets in the gloom, and when a larger boulder falls in the distance, a deep rumble marks its descent into the gorge.

CD1-46: Manx Shearwater Puffinus puffinus Los Tiles, La Palma, Canary Islands, about 23:30, 22 April 2001. A male and female call to each other while flying through a forested gorge. The female is heard only at 0:05-0:13, 1:07-1:14 and 2:00-2:07. Background: falling rocks and stones. 01.014.MR.11556.12

This recording illustrates an early stage in courtship. The male’s calls contain few phrases and are given at rather frequent intervals. Many end with an exhaled note that is inflected strongly downwards. The female is being a little unresponsive, and the male has to work extra hard to sustain a duet with her. At 0:46 he can be heard to land with a brief clatter of wings, and call several times from the cliff, perhaps trying to lure her to his burrow. Otherwise, his calls seem to be given in flight.

So far, little study has been devoted to how Manx Shearwater vary their calls according to context. Indeed, the assumption in most studies seems to be that they do not. However, recent work by William Mackin (2004) on Audubon’s Shearwater P lherminieri encourages more careful listening. Individual male Audubon’s vary their calls according to three main behavioural contexts: a) responding to other males or playback, b) duetting with females in a burrow and c) lone males trying to attract a female, or inciting one to duet with them. Males in the first group give longer calls, ie, with more phrases, which are also louder and have a higher peak frequency in the exhaled notes. When males in the second group duet with females, each bird’s contribution is shorter, and they alternate in a regular way. Interruptions are usually during the inhaled breath note, or when the other bird falls silent for a second or more. Males in the third group give ‘truncated calls’, which are only a few phrases long and given in rapid succession. These begin normally, but end with a single exhaled note, rather than the usual breath note. Truncated calls are given only at a suitable nest site, before egg-laying, and usually when other males are not in the immediate vicinity. CD1-46 is the first published evidence that truncated calls also exist in Manx.

Manx Shearwater Puffinus puffinus, Carnsore Point, Wexford, Ireland, 15 September 2007 (Killian Mullarney)

For an example of a pair duetting in a burrow, listen to a recording made on Elliðaey in Vestmannaeyjar, Iceland, the world’s most northerly shearwater colony (CD1-47). The only Manx I found there were in a tiny colony near the landing on the eastern side. One or two called in flight, flying back and forth over a small knoll. They must have had some difficulty avoiding collisions with the thousands of Leach’s Storm Petrels and Atlantic Puffins sharing the same airspace. Inside the knoll, a pair of pre-breeders were probably gearing up for their first breeding attempt the next year. Listen to the rather civilised way they take turns to call. The male leads with two or three phrases of song, then stops as soon as the female interrupts him with a slightly longer contribution, usually at the end of a breath note. When she is finished, the male starts calling again.

These Manx Shearwaters are not as easy to sex as the ones flying through the gorge on La Palma. There is very little difference between them in phrase length or calling rate. The male uses more harsh sounds than most, and the female uses some notes that are harmonic in structure. In Audubon’s Shearwater, Mackin (2004) observed that female exhaled notes became more male-like at low intensity, although fundamental frequencies in females were usually about half those of males. In CD1-47, frequency is the best distinction between the male and the female Manx. Probably, they are calling at less than maximum volume, to avoid being too conspicuous to predators, such as Great Black-backed Gulls Larus marinus. And anyway, why call at full intensity when your intended listener is right beside you in the same burrow?

CD1-47: Manx Shearwater Puffinus puffinus Elliðaey, Vestmannaeyjar, Iceland, 01:00, 20 July 2003. Duet of a male and female in a burrow. The male usually calls first, and is interrupted by the female. When she has finished calling, he starts again. Background: Leach’s Storm Petrels Oceanodroma leucorhoa. 03.034.MR.10601.02

Perhaps the most striking difference between the recordings from three widely separated locations – St Kilda in Scotland, La Palma in the Canary Islands, and Vestmannaeyjar in Iceland – is the prevalent acoustics. The St Kilda recordings were made on a steep boulder-field about 300 m above the sea, the La Palma ones in a forested gorge 5 km inland, and the Icelandic ones in a grassy knoll on flattish ground, only a few metres from the edge of a low cliff. In all three recordings, the shearwaters clearly sound as if they belong to the same species, but just how much do their calls vary across such wide expanses of the North Atlantic?

When James (1985a) analysed calls from widely dispersed Manx Shearwater colonies, he discovered small average differences, local accents too subtle for a human listener. His analysis involved up to eight measurements of frequency and timing, including the length of the call. Average male phrase lengths varied from 1.40 sec on Skokholm to 1.55 sec on Rhum, Scotland. For females, the extremes were 1.1 sec on Skomer and 1.21 sec on Rhum. In a later study (Wood 1999), calls were even found to differ slightly between two colonies on the small island of Bardsey, Wales, such that 75% of individuals could be correctly assigned to one of these two colonies by statistical methods. Strong individual variation made it impossible to classify them all.

Manx Shearwater Puffinus puffinus: known breeding distribution.

Recording locations indicated by arrows (north to south):

Ellidaey, Vestmannaeyjar, Iceland;

St Kilda, Western Isles, Scotland;

Skellig Michael, Kerry, Ireland;

Los Tiles, La Palma, Canary Islands.

The cause of this geographical variation has not yet been fully explained. One hypothesis is that, to some extent, Manx Shearwaters copy or learn their sounds from neighbours, leading to a convergence in the calls of birds from the same locality. This is how song dialects are thought to develop in songbirds. However, James (1985a) found that neighbouring birds did not have calls more similar to one another than to more distant, but potentially interbreeding birds in the colony. The possibility remains that nestlings learn from family and neighbours, before returning to breed in other parts of the colony. To test this, Bretagnolle (1996) tried a cross-fostering experiment with Snow Petrels Pagodroma nivea and Cape Petrels Daption capense. Five Snow Petrel nestlings brought up by Cape Petrels developed perfectly normal calls of their own species. This seems to exclude the possibility that petrels learn their sounds from their parents.

Another possible explanation for geographic variation is that shearwaters might adapt their calls for maximum propagation in differing environments. Could it be that Manx living near crashing waves call differently from those at quiet inland sites? The vocally divergent colonies on Bardsey were indeed located in different acoustic surroundings. However, three colonies on Skomer, despite being in contrasting acoustics, all shared the same ‘local accent’ (Wood 1999).

Perhaps the most likely cause of geographical variation in Manx Shearwater calls is simply genetic drift. Petrels, especially males, are generally very faithful to breeding sites, or ‘philopatric’. Given that no ringed Manx have ever been found to move between Scottish and Welsh colonies (Wernham et al 2002), it is noteworthy that the greatest geographical differences detected in calls are between Rhum in Scotland and Skomer in Wales. Interestingly, geographical variation is less apparent in the calls of females than in males (James 1985a). Males are more likely to return to their natal colony, while up to 50% of females nest elsewhere (Brooke 1990). Manx from Skokholm have been recovered on Pico in the Azores (Le Grand 1993) and on New Lawn Island, Newfoundland (Storey & Lien 1985). The first inland record for North America was a male ringed as a chick at Copeland Bird Observatory, Northern Ireland, on 7 September 1991 and found alive in the yard of a family home at Armada, Macomb County, Michigan, USA, on 19 August 2000; it died on 24 August at Detroit Zoo where it had been taken into care. In June 2004, one was found as far inland as Montana, USA (van den Berg 2000, 2004). The existence of some population exchange between colonies presumably keeps geographical variation in check, and stops ‘international’ communication from breaking down entirely.

Manx Shearwater Puffinus puffinus, Carnsore Point, Wexford, Ireland, 15 September 2007 (Killian Mullarney)

Manx Shearwaters Puffinus puffinus, Common Black-headed Gulls Chroicocephalus ridibundus and British Herring Gulls L argentatus argenteus, Carnsore Point, Wexford, Ireland, 15 September 2007 (Killian Mullarney)

A late August visit to Skellig Michael, an island off the coast of Kerry, Ireland, gave me a great opportunity to learn about the sounds of Manx Shearwater family life. 1300 years ago, Skellig Michael was home to a thriving monastery, perched atop one of the highest points of the island. Nowadays, day-trippers climb the 600 stone steps of the so-called ‘stairway to heaven’ to visit its well-preserved ruins. In the past, the monks used to sleep in stone cells shaped like old-fashioned, round beehives. I needed to crouch to get through the low entrance of one such ‘beehive hut’. Inside, it was pitch dark, much darker than outside. A high-pitched, rhythmic peeping could be heard coming from one corner, and I knew it was a Manx nestling. I did not want it to stop calling, so I laid down my microphone as quietly as I could and made a recording (CD1-48). When I had recorded enough, I was unable to resist turning on my head-torch for a moment. In late August, young Manx are fatter than their parents, and two layers of down make them look larger still. The nestling dwarfed another, more advanced youngster nearby, which had lost its down and was in fresh juvenile plumage. I left the nestling calling as intensely as when I arrived. Perhaps it was used to people, since tourists peered into the cell every day.

CD1-48: Manx Shearwater Puffinus puffinus Skellig Michael monastery, Kerry, Ireland, 04:52, 27 August 2006. Rhythmic calls and single chirps by a hungry nestling inside a monk’s stone cell. Background: British Storm Petrel Hydrobates pelagicus. 060827.MR.45233.01

A few hours previously, I felt my way through the small central passageway of the monastery. Following the wingbeat trajectories of non-calling Manx Shearwaters overhead, I went up some small steps, along another pathway between stone walls, and into a little annex. Close to the edge of the precipitous east cliffs, I heard several Manx nestlings calling from burrows under grassy slopes, just beside the monastery walls. Edging closer, I had to be very careful not to slip on the wet White Campion Silene latifolia. As I crouched down to listen, an adult landed on the ground with a resonant thump. It had probably been away for a couple of days, fishing goodness knows where. Wasting very little time, it headed straight into a burrow.

Manx Shearwater Puffinus puffinus, nestling inside a beehive hut, Skellig Michael, Kerry, Ireland, 26 August 2006 (Killian Mullarney). This is the nestling in CD1-48.

In CD1-49, you can hear what happened as this adult fed its young. The nestling’s calls are almost non-stop, and the parent can be heard quite often as well. Most of the time, the adult ‘chats’ quietly with the nestling. Once or twice it calls loudly, but not enough for me to sex it with confidence. The nestling gives a fast burst of ‘rhythmic calls’ to get proceedings started. Then ‘long begging calls’ are heard throughout the rest of the recording, while the nestling is actually being fed. Occasionally the calling stops, and you can hear the bill contact of adult and nestling.

Manx Shearwater Puffinus puffinus Skellig Michael, Kerry, Ireland, 23:21, 26 August 2006. Long begging calls of a nestling being fed by an adult. It gives occasional rhythmic calls as well. The adult ‘chats’ to it with short, quiet calls, and occasionally calls much more loudly. At 2:00 the calling stops briefly and bill contact can be heard. Background: wingbeats of individuals flying over. 060826.MR.232106.00

Like Cory’s Shearwaters Calonectris borealis, Manx Shearwater nestlings are able to indicate honestly how hungry they are by their rate of calling (Quillfeldt et al 2004). Curiously, when this rate of calling changes, the two parents react in very different ways. Female Manx readily adjust the size and frequency of meals, reacting more sensitively than males. Yet female Manx are not necessarily better parents, because males feed the nestling more frequently and regularly, providing about 58-59% of its diet. When researchers supplemented nestling diets by about 25%, both parents took note, and reduced supplies by almost exactly the same amount (Hamer et al 2006). The researchers concluded that a certain threshold had to be reached before the male would change its behaviour. For female Manx, food provisioning may be more costly, leading them to respond more precisely to cues from their nestling.

Nestlings of Manx Shearwater are quite unable to recognise their parents’ voices, and vice versa (Brooke 1978). This is in contrast to other colonial seabirds such as terns and auks (Tschanz 1968). Perhaps Manx nestlings do not need to recognise their parents. Even if they hear their parents some distance away, it is safest to stay in their burrow. When nestlings stay put, returning adults can safely assume that the one they find in their burrow is their own. In cross-fostering experiments, oblivious foster parents brought up chicks taken from other nests just as successfully as if they were their own (Brooke 1990).

The only time when adult shearwaters might not find their young in the nest is during the last week or so before they fledge. This is when the juveniles come out and exercise their wings, usually not very far away from their burrow, retreating underground before dawn. The nestling in CD1-49 probably fledged within a week or two. Perhaps it wandered around the colony for several nights, waiting for a north-easterly wind it could fly into. One night it finally took the plunge, gliding down and splashing into the sea some 200 m below, ready to start the long journey south.

Manx Shearwater Puffinus puffinus, colony, Skellig Michael, Kerry, Ireland, 25 August 2006 (Pim Wolf). CD1-45 and CD1-49 were recorded here.