Killian Mullarney

Text by Magnus Robb.

Bulwer’s Petrels Bulweria bulwerii are entirely silent in flight, and the only thing you might hear as they fly in from the sea is a faint whisper of their wings. Against the roar of surf on the rocks, they can easily go unnoticed, until one crashes against your limbs, head or clothing. This was how I met my first Bulwer’s in August 2001, when Roy Slaterus and I visited a colony on Ilhéu do Farol, an islet off the east end of Madeira.

Scent, rather than sound, may dominate interactions between Bulwer’s Petrels. In contrast to the aerial displays of gadfly petrels, they call only from burrows, and Thibault & Holyoak (1978) suggested that an especially strong odour formed part of their courtship displays. Like all other petrels, Bulwer’s have prominent horny tubes enclosing their nostrils, above and near the base of the bill. Indeed, petrels are often referred to collectively as ‘tubenoses’, because this is the main anatomical feature that unites the Procellariiformes and distinguishes them from their nearest relatives the penguins Sphenisciformes.

Although a world of scent is hard for us to imagine, many of our fellow mammals, both nocturnal and diurnal, are among its inhabitants. Picture a Bulwer’s Petrel, nose down and flying just above the surface, tracking the scent trails of distant squid and zooplankton. The terrestrial equivalent might be a fox, or a hound. By sheer coincidence, that’s exactly how Bulwer’s sound! At night their presence is betrayed by a quiet, dog-like barking, and there is little risk of confusing them with anything else (CD1-12). The Polynesians of Hawaii have a wonderful onomatopoeic name for Bulwer’s Petrel, which also breeds in the Pacific. They call it simply the “ou”.

CD1-12: Bulwer’s Petrel Bulweria bulwerii Selvagem Grande, Selvagens, 23:00, 27 June 2006. Duet calls and repeated calls of two individuals. The nearer bird is of unknown sex, but the more distant one can be sexed as a female. Background: Cory’s Shearwater Calonectris borealis, Barolo Shearwater Puffinus baroli and Madeiran Storm Petrel Oceanodroma castro. 06.008.MR.03111.00

In late June 2006, after listening to Zino’s Petrels Pterodroma madeira on Madeira, Killian and I sailed south from Madeira on the Ventura do Mar with a group of Irish and Portuguese friends. Our destination was the tiny Selvagens archipelago, midway between Madeira and the Canary Islands, a dream destination for anyone interested in Western Palearctic seabirds. Arriving at Selvagem Pequena, we had to negotiate some reefs and islets before we found a suitable place to anchor. Aidan Kelly was the first to notice calls of a Sooty Tern Onychoprion fuscatus flying over the Common Tern Sterna hirundo colony in the western part of the island. We could hardly wait to get a closer look, but the Sooty promptly disappeared. Once ashore, we were met by a friendly warden, weathered and close to retirement age. He was taking his turn to live in its only building, a small wooden hut lacking even the luxury of a fridge. With him was an attractive young marine biologist who was staying on the island for a couple of weeks. The thought that she might actually be a mermaid distracted us from the missing tern for the time being.

Selvagem Pequena’s flat, sandy surface is almost completely riddled with burrows of one of the largest colonies of White-faced Storm Petrel Pelagodroma marina in the Atlantic. The fragility of the colony meant that our movements were largely restricted to the island’s shore. One of the first things we were shown was a Bulwer’s Petrel nesting inside a large rock, not far above the high water mark. Blinded by the reflection of bright sunlight on the sandy beach, it took some time to adjust to the dark crevice, and eventually we could all see the incubating petrel inside.

Bulwer’s Petrel Bulweria bulwerii, on its nest, Selvagem Pequena, Selvagens, 26 June 2006 (Killian Mullarney)

After dark, several Bulwer’s Petrels could be heard calling from rocky outcrops around the margins of the sandy island. Their vocal repertoire was not quite as simple as suggested by the Hawaiians, because the ou notes were given in structured sequences. Most calls of adults can be put in two general categories: ‘duet calls’ and ‘repeated calls’ (Bretagnolle 1996). Duet calls are used in interactions, either with other Bulwer’s, or in reaction to playback or imitations. It is quite easy to get a Bulwer’s to ‘talk’ by imitating these little barks. Duets in this context should not be taken to mean male-female courtship. As the next two recordings show, duet calls can also be used in same-sex interactions.

Duet calls follow a cyclical rhythmic pattern consisting of three parts. In the sonagrams, I have labelled them A, B and C for simplicity. The A section can just be a single, rather emphatic bark as in the opening seconds of CD1-13, but sometimes this is followed after a second or more by one or two quieter ones, as at the start of CD1-14. The B section is a silence of fixed length, consistent for each individual and usually about 4-6 sec long, Finally, the C section consists of two short barks about half a second apart. Duet calls rarely end after a single cycle, and the repeating sequence of A, B, C, A, B, C, A, B… can be broken at any time.

CD1-13: Bulwer’s Petrel Bulweria bulwerii Selvagem Pequena, Selvagens, 01:13, 27 June 2006. Calls of two females under a rock, after the recordist had barked a crude imitation. The recording starts with a typical duet call by the nearer female. The other female does not appear until later in the recording. Background: distant surf. 060627.MR.11355a.00

CD1-14: Bulwer’s Petrel Bulweria bulwerii Selvagem Pequena, Selvagens, 01:13, 27 June 2006. A continuation of CD1-13, starting where the latter ended. The recording starts with a duet call, which has a two-note A section. Background: distant surf. 060627.MR.11355b.00

Duet calls typically alternate with bouts of repeated calls, which are long series of short barks. The last bark of a series of repeated calls sometimes doubles as an A section of a duet call. Socialising Bulwer’s Petrels use both call types, but solitary individuals typically only give repeated calls.

James & Robertson (1985d) studied the calls of Bulwer’s Petrels whose sex had been identified in the hand. They found that both sexes used both main call types. Only repeated calls differed significantly between the sexes. In males, the silent interval between barks was longer, averaging 0.82 sec, compared to 0.68 sec for females. In other words, males deliver their barks at a slower tempo than females.

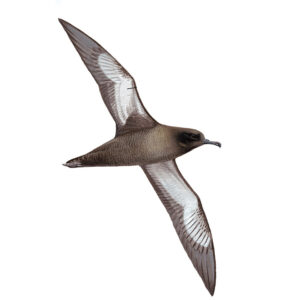

Bulwer’s Petrel Bulweria bulwerii, between the Selvagens and Madeira, 29 June 2006 (Killian Mullarney)

A male and female can be heard calling together in CD1-15, which was recorded on Ilhéu do Farol, Madeira. The male’s repeated calls are clearly a lot slower, with much longer gaps between barks. I believe that further work will result in more differences between male and female calls being discovered, perhaps in their frequency or timbre. Bretagnolle (1996) listed Bulwer’s Petrel as showing such differences, but gave no details.

CD1-15: Bulwer’s Petrel Bulweria bulwerii, Ilhéu do Farol, Madeira, 8 August 2001. Duet calls and repeated calls of a male (slightly closer) and female. The male’s repeated calls are delivered much more slowly than the female’s. Background: Madeiran Storm Petrel Oceanodroma castro and surf. 01.035.MR.05557.00

The differences between male and female repeated calls are often more subtle than in CD1-15, and there is plenty of overlap in their timing (James & Robertson 1985d). In the first track you heard, for example, the nearer bird could not be sexed. But perhaps sounds are only a secondary sexual signal in Bulwer’s Petrel. It is quite possible that scent is their principle means of telling each other’s sex in the dark. According to Thibault & Holyoak (1978), Bulwer’s have a different and much stronger, pungent odour during a short period before the egg is laid, and perhaps this coincides with the peak of sexual activity in the colony. When we visited the Selvagens in late June, the period for this peculiar odour had long passed, and I cannot say I could distinguish Bulwer’s in the general scent of the large mixed colony. But observations at sea did convince me that Bulwer’s is a species for which scent is of great importance.

Bulwer’s Petrel Bulweria bulwerii, between Madeira and the Selvagens, 25 June 2006 (Killian Mullarney)

The Bulwer’s Petrels we saw from the Ventura do Mar were always a delight to watch, and one of the most abundant seabirds we encountered during the voyage. Slender-winged, with a long, wedge-shaped tail, Bulwer’s are smaller than a Pterodroma, but larger than any storm petrel. Their plumage is very dark brown, appearing blackish most of the time, and our crew called them ‘alma negra’, which means ‘black soul’ in Portuguese. The only contrast is on the upperwing, where there is a paler brown bar that can appear golden in evening sunlight. In moderate winds, Bulwer’s’ manner of flying is as characteristic as its rakish outline. Weaving and twisting gracefully over crests and troughs, it holds its wings forward and often slightly bowed while facing into the wind. Bulwer’s is actually more buoyant in flight than any other petrel, even including storm petrels (Warham 1996). Nevertheless, a powerful attraction seems to keep Bulwer’s from rising too high above the sea; they never tower above it like gadfly petrels.

Bulwer’s Petrels Bulweria bulwerii, near the Selvagens, 25 June 2006 (Killian Mullarney)

Many petrels have an exceptional sense of smell, and this helps them to find their food on the vast oceans. Birders on pelagic trips exploit this when foul-smelling chum, consisting of bits of rotting fish, guts and oil (sometimes with a bit of birder’s vomit thrown in) is dumped overboard. The effects can often be dramatic, as storm petrels come streaming in from all directions over a seemingly empty sea. We did no chumming on our trip to the Selvagens, but Bulwer’s Petrel’s sense of smell was nicely illustrated when Jorge Alves, our cook on the Ventura do Mar, was frying fish for dinner. Several of the closest fly-bys of the whole trip came from downwind, behind the boat, and flew past on the port side where the galley window was open. Low flight into the wind is consistent with tracking food odours, and perhaps scent is the reason Bulwer’s has evolved its characteristic mode of flight (Verheyden & Jouventin 1994).

Such a buoyant seabird probably obtains much of its food on the wing, and Bulwer’s Petrels will even catch flying fish when the opportunity arises (Zonfrillo 1986). They are also known to make shallow dives, attaining a mean maximum depth of 2.4 m (Mougin & Mougin 2000). The Bulwer’s we saw during the Selvagens trip seemed to be constantly on the move, although during the return trip we occasionally disturbed resting groups of up to eight from the surface. None of the ones we saw from the boat were actually feeding. This puzzled me at the time, but having read some more, I believe this is because they mainly feed at night. Most of their known prey species are bioluminescent, migrating to surface waters in the dark (Zonfrillo 1986, Harrison et al 1983).

In the Western Palearctic, Bulwer’s Petrel is only really common in Madeira, the Selvagens and the Canary Islands. Small populations also breed in the Azores and the Cape Verde Islands. After the breeding season, they move to areas of nutrient-rich upwellings that form in autumn off the north-eastern coast of Brazil, and stay there for the winter (van Oordt & Kruijt 1953). Over a vast breeding range, their breeding biology, phenology and physical appearance are remarkably consistent, and no subspecies have been described. However, the Bulwer’s breeding on the Cape Verde Islands are worthy of note. Like two small populations from the Pacific, they take advantage of upwellings that occur in late winter, and breeding starts a couple of months earlier than further north. They also breed over a longer period, with eggs reported as early as January, and nestlings as late as September (Hazevoet 1995).

Bulwer’s Petrel Bulweria bulwerii: known Atlantic breeding distribution (red dots). Recording locations indicated by arrows (north to south): Ilhéu do Farol, Madeira; Selvagem Grande & Selvagem Pequena, Selvagens.

During a March 2007 visit to the Cape Verde island of Raso, I located one of their main breeding areas when I found skulls and other remains scattered over an area of suitable, boulder-strewn habitat. The most poignant remains were those of a female that had died on the point of laying her egg, one or two breeding seasons before. I returned to the same area at night, but was unable to hear a single bark. This was a bit of a mystery, given that they should have been well into their breeding season.

Bulwer’s Petrel Bulweria bulwerii, skeleton and egg, Raso, Cape Verde Islands, 20 March 2007 (René Pop)

Look at the size of the single egg inside the female’s abdomen. It is huge! Forming an egg that size requires a lot of energy, and excellent feeding conditions. No wonder then that after fertilisation, females desert the colony on a pre-laying exodus, which allows them to feed at a considerable distance from the colony. Further north, Bulwer’s Petrels from the Desertas, both males and females, desert their colony for an average of 29 days (Nunes & Vicente 1995). So perhaps my visit to Raso coincided with this pre-laying exodus.

The first time I ever heard Bulwer’s Petrel, on Ilhéu do Farol, Madeira, was at a much later stage of the breeding season. Thrilled by our first-ever encounters with Bulwer’s, and Madeiran Storm Petrels Oceanodroma castro, in a pile of boulders down near the shore, Roy and I finally rolled out our sleeping bags beside a knee-high stone dyke. Some time after Roy nodded off, a storm petrel fluttered over him, narrowly missing his nose, and disappeared into the wall behind us. It started duetting with its mate. A few stones further, just a metre from where I was lying, a long series of quiet peeps could be heard. My torch revealed a fluffy Bulwer’s nestling in a cavity just centimetres away from the outside world. From the comfort of my sleeping bag (CD1-16), I recorded both species, then rolled over and went to sleep.

Bulwer’s Petrel Bulweria bulwerii, nestling, Ilhéu da Vila, Santa Maria, Azores, 6 August 2007 (Verónica Neves)

CD1-16: Bulwer’s Petrel Bulweria bulwerii, Ilhéu do Farol, Madeira, 02:00, 8 August 2001. Begging calls of a nestling, showing rhythmic patterns not dissimilar to adults: single notes, doubled notes and repeated notes. Background: interjections from male then female Madeiran Storm Petrels Oceanodroma castro. 01.036.MR.02258.00