Undiscovered Owls – web book

Introduction

Like a crescent moon in a bright blue sky, an owl can evade discovery without even trying. Take away the daylight, the scattered clouds, the landscape and the face of a companion, the moon will be no brighter than before, but because there are fewer distractions it will be hard to miss. With an owl, the distraction is noise. Machinery and traffic, talking and barking, turbulent wind and water, it need not be deafening. Just enough to clutter our minds. Clear it away and a distant owl may resonate with the very core of our being.

Under a full moon we can see forests and rocks, creatures and almost any decent sized objects in our surroundings. Arguably, we are just seeing moonlight reflected off those objects, reaching us along myriad pathways and after all, the moon itself is only reflecting the sun. When a distant owl hoots, its sound ‘illuminates’ the surroundings. We never think of it this way, but countless owl-echoes allow us to ‘hear’ trees, fields and cliffs. We may not perceive each item separately but when blurred together, they form an integral component of an owl’s sound.

On a recent trip to Sweden, Håkan and I spent several nights listening for Tengmalm’s Owls Aegolius funereus. We would stop the car and listen outside for a couple of minutes, until either we heard an owl or the cold forced us back inside. In some areas we would find a new Tengmalm’s every two kilometres or so, usually sounding incredibly distant in snowy, dense coniferous forest. On that far horizon where sound grades into imagination, the hooting sometimes disappeared, then reappeared. Slight changes in the breeze can cause this, but I believe the sound was so faint that it was moving in and out of consciousness. The more repetitive and continuous a sound, the more easily it slips away. Irregular patterns grab our attention more easily, even at the edge of perceptibility.

In reality, true silence is as rare as a Snowy Owl Bubo scandiacus in a hot, sandy desert. There is always audible habitat or ‘atmos’. Like us, owls filter out what is constant and concentrate on irregular movements. Their filters are infinitely more refined. In our ears a rustle or a scamper, a nibble or a squeak will usually fail to register. For an owl these are exactly the sounds that matter, these and the voices of other owls much further away.

In trying to identify owls to species, I find that it helps to know which kind of calls I am likely to hear when. The simplest solution is to divide an owl’s year into three main periods. First there is courtship, usually early in the year. From incubation until after the young fledge a new set of sounds gradually emerges. Finally, territorial sounds predominate after the young leave their parents, at least in those owls that are year-round residents.

At the start of courtship, male and female are usually aggressive towards one another, before they gradually settle into very different roles. The male must demonstrate his ability to catch enough prey or the female will not lay eggs. He does this through courtship feeding, a ritual accompanied by music. The male’s contribution is his ‘song’. In barn owls Tytonidae this is a repetitive, modulated screeching (at least in the Western Palearctic), and in the Strigidae it is hooting. The female responds with simple calls telling the male where she is and reminding him of his obligation to feed her. It would be tempting to name these ‘begging calls’ or even ‘demanding calls’ but males often produce an almost identical sound without asking anything from females except their cooperation. So I prefer to call these ‘soliciting calls’. Several other sounds are characteristic of the courtship period. These include simple, rapidly repeated nest-showing calls and high-pitched copulation calls.

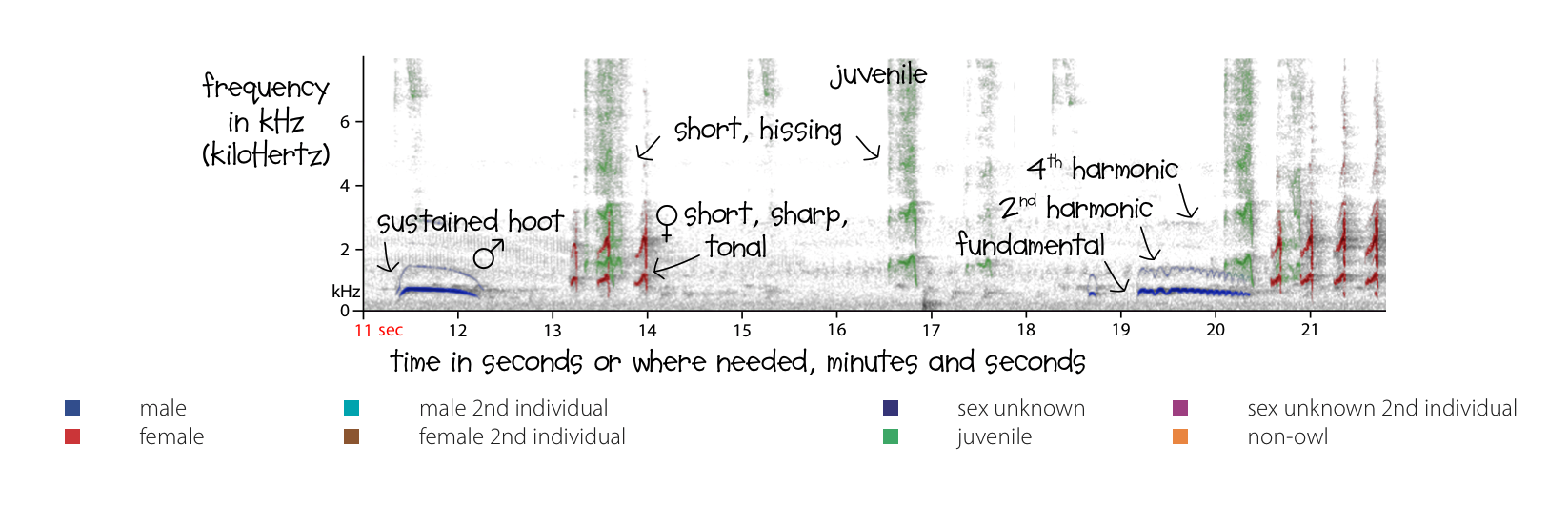

The sonagram above is derived from CD4-28 (Tawny Owl Strix aluco) and is repeated with different annotations later in the book. Owl sounds make thankful subjects for sonagrams, because they produce simple patterns. The vertical axis of a sonagram represents the pitch, while the horizontal axis represents time. We recommend paying particular attention to the lowest trace, the one nearest to the horizontal axis. This is the fundamental, the component that usually determines how we hear the pitch of the sound. The higher bands, when present, are harmonics and other features that determine the timbre or ‘colour’ of the sound. They tend to disappear with distance, leaving only the fundamental. The rhythm of an owl call can be deduced from the horizontal spacing. On a very basic level, a long, sustained, tonal sound will show as a horizontal line whereas a very short, harsh one will show as a vertical line. Likewise, a long horizontal space corresponds to a long time interval between sounds and vice versa. Within each genus, I have made sonagrams at only one or two different frequency scales to facilitate comparison. The colour coding is as shown here. Where there is significant doubt about the sex, I have used purple, with magenta indicating a second unsexed individual. Where there is only minor doubt, I sex them as I believe correct and add the annotation ‘presumed male’ or ‘presumed female’.

After laying their clutch, most owls become very quiet. We still hear the male’s song and the female’s soliciting calls, but only during the male’s brief visits to the nest. After the young hatch, there is much more to listen to. The female’s staccato ‘feeding calls’ are often the first sign that young have hatched, before their begging calls gradually become the dominant sound around the nest. Meanwhile, the male visits more frequently, and both adults become more nervous about intruders, especially as fledging time approaches. This is when we hear excitement calls and sometimes even weird displays designed to lure us away. We could be lazy and call these ‘alarm calls’, but birds do not call just for the sake of expressing emotions. When threatened they adopt a strategy, which may be to warn their loved ones (‘hide!’), to call for reinforcements (‘help!’), or even to threaten their enemy (‘you’re dead meat!’).

Owls that are year-round residents usually have a secondary peak of calling in autumn. Some simply draw a few calls from the repertoire they use all year round. Others have special autumn sounds, or calls heard rarely at other times. In a few partially migratory or nomadic species, autumn calling is rare but still well worth listening for. There are one or two that we have never heard during this season, although other listeners have.

Our species taxonomy does not follow any existing authority, nor does it pretend to be one. Taxonomy is in constant flux, and in this book we based ourselves upon what was known and published on the 1st of January 2015. Subdividing the natural diversity around us is a basic human need and birthright (Shepard 1978), and we have identified what we believe to be the owl species of the Western Palearctic to the best of our abilities. Our species limits are hypotheses and we do not pretend that they are facts. The approach is integrative, considering multiple strands of evidence to decide whether a particular taxon represents a separate branch on the tree of life. Although sounds are of prime importance when defining nocturnal bird species, we have also considered genetics (monophyly), morphology (distinct appearance), geography (degree of isolation) and ecology (differences in niche) whenever possible.

When lineages diverge, different characters and ‘species properties’ evolve at their own pace, depending on which pressures are operating. In integrative taxonomy the absence of one such property, such as a distinct plumage, does not invalidate species rank if there is other strong evidence supporting it (Sangster 2013). Sometimes, sounds may differ between two populations when the genetic difference between them is tiny. Other times, different conditions in isolation can bring about changes in plumage and body proportions while sounds hardly change at all.

Owls often force us out of our comfort zone. At a basic level, we usually have to endure cold and darkness. In Portugal where I live, cold is not a problem and I am not afraid of the dark, but I still have to be prepared for the unexpected. Other people’s fears pose the most serious threat. Once I drove through an open gate near a road, but with no inhabited houses anywhere in sight. Leaving my car in view of the road, I walked over the top of a hill to investigate a ruin that looked good for Common Barn Owl Tyto alba and proved to be full of pellets. When I went back over the hill I was blinded by searchlights from a police car, and walked as calmly as I could to meet them and explain myself. So far, I have not met a gun in the dark but it could happen at any time.

One of the good things about owling in Portugal is that I am allowed to be responsible for my own safety. Many sites are accessible that would be fenced off in Scotland, where I was born. Even an old mine complex with vertical shafts, pools of colourful, strange-smelling liquids and buildings on the point of collapse is open to anyone curious enough to go there. And curiosity usually gets the better of me.

Contents

Acknowledgements

The Sound Approach is a complex organism that once began as a team of three birders: Arnoud van den Berg, Mark Constantine and myself, Magnus Robb. Three more – Dick Forsman, Killian Mullarney and René Pop – have become key members over the years, and all played an important role in the preparation of this work. When the time came, our design duo – Cecilia Bosman and Mientje Petrus – converted the raw materials into book form. Cecilia also supported Arnoud on many of his recording trips, and Mo did the same for Mark. I wrote the text in the first person, borrowing extensively from the thoughts and experiences of other team members. Any mistakes are, however, my own.

Killian provided the Omani Owl and Turkish Fish Owl for the cover, as well as the Cucumiau and Short-eared Owl used on the CDs. He and Dick both recommended Håkan Delin to be the illustrator for this book. Håkan has been watching and listening to owls with meticulous attention to detail for most of his life, and his collected owl wisdom was an invaluable bonus to this project.

Three sound recordists – Johannes Honold, João Nunes and Peter Nuyten – went out and made additional sound recordings at our request. Several others had very special sounds in their collections, which they allowed us to use: Fabio Cherchi, Roland Eve, Patrick Franke, Hannu ‘Honey’ Jännes, Jelmer Poelstra, Davide De Rosa and Ove Stefansson. Saydisc Records gave us permission to use a recording by Ian Strange, and The Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology allowed us to use recordings by Richard J Clark, William W H Gunn, David Herr, David Moyer, Leonard J Peyton, Philip Taylor and Gerrit Vyn. We have many friends at the Lab, but would like to thank Greg Budney and Matthew Young in particular for their assistance.

It would have been impossible to record and photograph owls in so many locations without a great deal of local help. We would like to thank the following people for information about where to search, assistance in the field and/or hospitality: Kari Ahola/KBP, Per Alström, Vasil Ananian, Soner Bekir, Letizia Campioni, Carlos Carrapato, Giusi De Castro, Carlos & Claudia Cruz, Hassan Dalil, Piotr Debowski, Hampus Delin, Hugues Dufourny, Isabel Fagundes, Pedro Fernandes, Inki Forsman, Sandeep Gaonkar, Dimiter Georgiev, Hamida Hammouradia & family, Heikki Henttonen, Juha Honkala, Mike Jennings, Tomasz Jezierczuk, Özcan Kilic, Erkki Korpimäki, Olli Lamminsalo, Alexandre Leitão, Lorenzo Di Lisio, Heikki Lokki, Matilde Londner, Rui Lourenço, Pedro Marques, Mireia Martín, Teresa Massarella, Łukasz Mazurek, Dave McAdams, John McLoughlin aka Johnny Mac, Istvan Moldovan, Colm Moore, Antonio-Roman Munoz, Seppo Niiranen, Paulo Oliveira (Parque Natural da Madeira), Lahcen Ouacha & friends, Carlos Pacheco, Nino Patti, Fabian Pekus, Vincenzo Penteriani, Antti Peuna, Geoff Phillipson, Kari Pihlajamäki, Benjam Pöntinen, Pekka Pouttu, Vladimir Pozdnyakov, Torsten Pröhl, Beneharo Rodríguez, Luis Roma, Pertti Saurola, Georg Schreier, Sebastian Siebold, Roy Slaterus, Yuri Sofronov, Qupeleio & Jennifer De Souza, Matti Suopajärvi, Ibrahim Tuncer, Aarto Tuominen, Andrew Upton, Hannu Velmala, Sten Vikström, Noam Weiss, Dick Woets and Emin Yoğurtcuoğlu. Amanda Taylor of Lush organised the logistics of several of our trips. Paul Morton and Kerry Fletcher took care of me, no matter how pathetic my requests.

Håkan Delin at cliff of Pharaoh Eagle-Owl Bubo ascalaphus, Jebel Lamdouar, Rissani, Tafilalt, Morocco, 11 March 2012 (Arnoud B van den Berg). Same site as in CD3-20 and CD3-24.

My understanding of owl sounds was considerably enriched by those who allowed access to reference recordings. These included Vaughan & Svetlana Ashby, Raffael Ayé, Jan-Erik Bruun, José Luis Copete, Andrea Corso, Pierre-André Crochet, Peter Flint, Karl-Heinz Frommolt (Tierstimmenarchiv.org), Bernard Geling (Birdsounds.nl), Lauri Hallikainen (personal.inet.fi/ yritys/kultasointu), Micha Heiss, John Keane, Sander Lagerveld, Harry Lehto, Antero Lindholm, Ralph Martin, Les McPherson (archivebirdsnz.com), Joseph Medley & the United States Forest Service, Manuel Schweizer, Pratap Singh, Martyn Stewart (naturesound.org), Cheryl Tipp (bl.uk/soundarchive), Deepal Warakagoda and Mike Watson. I also referred extensively to: Avian Vocalizations Center (avocet.zoology.msu.edu), the Internet Bird Collection (ibc.lynxeds.com), the Borror Library of Bioacoustics (blb.biosci.ohio-state.edu) and of course, Xeno-canto (xeno-canto.org). For the maps, we consulted various publications (eg, Hagemeijer & Blair 1992, König et al 2008, Jennings 2010, del Hoyo & Collar 2014 and various field guides). These books showed quite a lot of differences in their maps, reflecting both the dynamics of some species’ distribution and a lack of knowledge; the choices we made for this book are our own, partly based on personal experience. We are also very grateful to the following photographers who contributed their work: Eric Didner, Jo Latham, ‘Dirty’ James Lidster, Bruce Mactavish, Eric Meek, Paulo hiro, Artur Oliveira, Torsten Pröhl, Chris van Rijswijk, Domingo Trujillo and Mike Watson. We also thank Shaun Robson for making a book like this necessary.

Luis Gordinho and Ricardo Tomé gave valuable suggestions after reading sections of the manuscript. Nick Hopper helped to popularise the sonagram annotations. André van Loon, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and Thor Veen enabled me to obtain access to a wide range of scientific literature, which enriched this book immeasurably. Many others kindly replied to requests for literature or to specific questions. They included David Armitage, Patrick Bergier, Keith Betton, Ruud van Beusekom, Karla Bloem, Leo Boon, Oscar Campbell, Robin Campbell, Geoff Carey, Yüksel Coşkun, Edward Dickinson, Harvey van Diek, Paul Doherty, Marc Duquet, Mark Eising, Javier Elorriaga, Janneke Eppinga, Jens & Hanne Eriksen, Rainer Ertel, Michael Exo, Rob Felix, Yuzo Fujimaki, Paolo Galeotti, Kai Gauger, Barak Granit, Hein van Grouw, Ricard Gutiérrez, Kees Hazevoet, Paul Holt, Wulf Ingham, David Insall, Sureyya Isfendiyaroğlu, Justin Jansen, Alan Kemp, Abolghasem Khaleghizadeh, Roy Kleukers, Peter de Knijff, Claus König, Michael Leven, Ian Lewis, Andreas Lindén, Antero Lindholm, Alex Masterson, Rafael Matias, Matthew Medler, Ugo Mellone, John Mendelsohn, Jonathan Meyrav, Nial Moores, Nick Moran, Babak Musavi, The Natural History Museum at Muscat, The Natural History Museum at Tring, Lajos Nemeth, János Oláh, Gert Ottens, Marco Pavia, Yoav Perlman, Shaun Peters, Matt Pretorius, Marius Puttmann, Ian Riddell, Kees Roselaar, Forrest Rowland, George Sangster, Wolfgang Scherzinger, Yevgeni Shergalin, Raquel Silva, Jonathan Slaght, James Smith, Stephen Smith, David Stanton, Elchin Sultanov, Lars Svensson, Warwick Tarboton, Michel Thévenot, Mohammad Tohidifar, Magnus Ullmann, Raju Vyas, Derek Whiteley, Rombout de Wijs, Frank Willems, Duncan Wilson, Pim Wolf, Yusuke Umegaki and Christoph Zockler. To anybody that I have omitted please understand that it’s my memory, not ingratitude.

For inspiration and infecting him with his fanatical interest in owls, Arnoud would like to thank Karel H Voous. For constant encouragement, we would like to thank Ian Wallace.

Manuela Nunes and our two boys Félix and Finn gave me a huge amount of support and patience as I worked on this book. I dedicate my work to all three, with love and gratitude.

References

Alcover, J A & Florit, X 1989. Els ocells del jaciment arqueològic de la Aldea, Gran Canària, Butlletí de la Institució Catalana d’Història Natural 56 (Secció de Geologia, 5): 47-55.

Alegre, J, Hernández, A, Purroy, F J & Sánchez, A J 1989. Distribución altitudinal y patrones de afinidad trófica geográfica de la Lechuza Común (Tyto alba) en León. Ardeola 36: 41-54.

Alexander, W B 1935. Minutes of the 377th meeting, December 12, 1934. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club 55: 60.

Ali, S & Ripley, S D 1981. Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan 3. Second edition. Delhi.

Aliabadian, M, Alaee, K, N & Darvish, J 2012. Phylogenetic systematics of Barn Owl (Tyto alba (Scopoli, 1769)) complex inferred from mitochondrial rDNA (165 RRNA) taxonomic implication. Journal of Taxonomy and Biosystematics 4: 1-12.

Antoniazza, S, Burri, R, Fumagalli, L, Goudet, J & Roulin, A 2011. Local adaptation maintains clinal variation in melanin-based coloration of European barn owls (Tyto alba). Evolution 64: 1944-1954.

Appleby, B M & Redpath, S M 1997. Indicators of male quality in the hoots of Tawny Owls (Strix aluco). Journal of Raptor Research 31: 65-70.

Aronson, L 1979. Hume’s Tawny Owl Strix butleri in Israel. Dutch Birding 1: 18-19.

Aulagnier, S, Haffner, P, Mitchell-Jones, A J, Moutou, F & Zima, J 2009. Mammals of Europe, North Africa and the Middle East. London.

Baha el Din, S & Baha el Din, M 2001. Status and distribution of Hume’s (Tawny) Owl Strix butleri in the Eastern Desert of Egypt. Bulletin of the African Bird Club 8: 18-20.

Bakker, D 1957. De Velduil in de Noordoostpolder. De Levende Natuur 60: 104-108.

Ballman, P 1973. Fossile Vögel aus dem Neogen der Halbinsel Gargano (Italien). Scripta Geologica 17: 1-75.

Bannerman, D A 1963. Birds of the Atlantic Islands 1: a history of the birds of the Canary Islands and the Salvages. Edinburgh.

Bannerman, D A 1965. Birds of the Atlantic Islands 2: a history of the birds of Madeira, the Desertas, and the Porto Santo Islands. Edinburgh.

Bannerman, D A & Bannerman, W M 1958. Birds of Cyprus. Edinburgh.

Bannerman, D A & Bannerman, W M 1966. Birds of the Atlantic Islands 3: a history of the birds of the Azores. Edinburgh.

Barn Owl Trust 2012. Barn Owl Conservation Handbook. A comprehensive guide for ecologists, surveyors, land managers and ornithologists. Exeter.

Bates, G L 1937a. On interesting Birds recently sent to the British Museum from Arabia by Mr. N. St. J. B. Philby. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club 57: 17-21.

Bates, G L 1937b. Descriptions of two new races of Arabian birds: Otus senegalensis pamelae and Chrysococcyx klaasi arabicus. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club 57: 150-151.

Beaman, M 1994. Palearctic birds. A checklist of the birds of Europe, North Africa and Asia north of the foothills of the Himalayas. Stonyhurst.

Beck, T W & Winter, J 2000. Survey protocol for the Great Gray Owl in the Sierra Nevada of California. Prepared for the US Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Region, Vallejo, California, USA.

Bekir, S, Yoğurtçuoğlu, E & Bozdoğan, M 2010. Balık Baykuşu (Bubo zeylonensis) Araştırma Raporu 2010. [Brown Fish Owl (Bubo zeylonensis) Research Report 2010.] (In Turkish.)

van den Berg, A B 1974. Merkwaardig gedrag van Velduilen op Schiermonnikoog. Het Vogeljaar 22: 830.

van den Berg, A B, Bekir, S, de Knijff, P & The Sound Approach 2010. Rediscovery, biology, vocalisations and taxonomy of fish owls in Turkey. Dutch Birding 32: 287-298.

van den Berg, A B, Bekir, S & The Sound Approach 2009. DBActueel: Brown Fish Owl in Turkey and first breeding record for WP. Dutch Birding 32: 268-270.

van den Berg, A B, Bison, P & Kasparek, M 1988. Striated Scops Owl in Turkey. Dutch Birding 10: 161-166.

van den Berg, A B & Haas, M 2005. WP reports. Dutch Birding 27: 403-425

Berggren, V & Wahlstedt, J 1977. Lappugglans Strix nebulosa läten. Vår Fågelvärld 36: 243-249.

Bergier, P & Thévenot, M 1991. Statut et écologie du Hibou du Cap Nord-Africain Asio capensis tingitanus. Alauda 59: 206-224.

Bondrup-Nielsen, S 1984. Vocalizations of the Boreal Owl, Aegolius funereus richardsoni in North America. Canadian Field Naturalist 98: 191-197.

Boukhamza, M, Hamdine, W & Thévenot, M 1994. Données sur le régime alimentaire du Grand-Duc Ascalaphe (Bubo bubo ascalaphus) en milieu steppique (Aïn Ouessera, Algérie). Alauda 62: 150-152.

Brazil, M A & Yamamoto, S 1989. The behavioural ecology of Blakiston’s Fish Owl Ketupa blakistoni in Japan: calling behaviour. P 403-410 in: Meyburg, B-U & Chancellor, R D (editors), Raptors in the modern world: proceedings of the III world conference on birds of prey and owls. World Working Group on Birds of Prey and Owls, Berlin.

Brito, P H 2005. The influence of Pleistocene glacial refugia on tawny owl genetic diversity and phylogeography in western Europe. Molecular Ecology 14: 3077-3094.

Broekhuizen, S, Hoekstra, B, van Laar, V, Smeenk, C & Thissen, J M B 1992. Atlas van de Nederlandse zoogdieren. Third edition. Utrecht.

Broggi, J, Copete, J L, Kvist, L & Mariné, R 2013. Is there genetic differentiation in the Pyrenean population of Tengmalm’s Owl (Aegolius funereus). Ardeola 60: 123-132.

Bühler, P & Epple, W 1980. De Lautäußerungen der Schleiereule (Tyto alba). Journal für Ornithologie 121: 36-70.

Bunn, D S, Warburton, A B & Wilson, R D S 1982. The Barn Owl. Calton.

Byrjedal, I & Langhelle, G 1986. Sex and age biased mobility in Hawk Owls Surnia ulula. Ornis Scandinavica 17: 306-308.

Cadman, W A 1934. An attacking Tawny Owl. British Birds 28: 130-132.

Canário, F, Leitão, A H & Tomé, R 2012. Predation attempts by Short-eared and Long-eared Owls on migrating songbirds attracted to artificial lights. Journal of Raptor Research 46: 232-234.

Carlyon, J 2011. Nocturnal birds of Southern Africa. Pietermaritzburg.

Catchpole, C K & Slater, P J B 2008. Bird song. Biological Themes and Variations. Second edition. Cambridge, UK.

Catry, P, Costa, H, Elias, G & Matias, R 2010. Aves de Portugal. Ornitologia do território continental. Lisbon.

Chappuis, C 2000. Oiseaux d’Afrique 1. Sahara, Maghreb, Madère, Canaries & Îles du Cap-Vert. 4 CDs and booklet. Paris.

Chappuis, C 2010. Review of Indian bird sounds. Dutch Birding 32: 132-133.

Chappuis, C, Deroussen, D & Warakagoda, D 2008. Indian bird sounds – The Indian Peninsula. 5 CDs and booklet. Hyderabad.

Charter, M, Peleg, O, Leshem, Y & Roulin, A 2012. Similar patterns of local barn owl adaptation in the Middle East and Europe with respect to melanic coloration. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 106: 447-454.

Clark, R J 1975. A field study of the Short-eared Owl, Asio flammeus (Pontoppidan), in North America. Wildlife Monographs 47: 3-67.

Clottes, J 2002. Paleolithic cave art in France. Adorant magazine, published online at www.bradshawfoundation.com

Constantine, M, Hopper, N & The Sound Approach 2012. Catching the bug. Poole.

Cramp, S (editor) 1985. The birds of the Western Palearctic 4. Oxford.

Delgado, M del M, Caferri, E, Méndez, M, Godoy, J A, Campioni, L & Penteriani, V 2013. Population characteristics may reduce the levels of individual call identity. PLoS ONE 8: e77557.

Delgado, M del M & Penteriani, V 2006. Vocal behaviour and neighbour spatial arrangement during vocal displays in eagle owls (Bubo bubo). Journal of Zoology 271: 3-10.

Deroussen, F & Millancourt, H 2003. Chouettes et hiboux de France et d’Europe. CD and booklet. Charenton.

Desfayes, M & Géroudet, P 1949. Notes sur le Grand-Duc. Nos Oiseaux 20: 49-60.

van Diek, H, Felix, R, Hornman, M, Meininger, P L, Willems, F & Zekhuis, M 2004. Bird counting in Iran in January 2004. Dutch Birding 26: 287-296.

Dorogov, I 1987. [Ecology of the rodent-eating predators of Wrangel Island and their role in lemming dynamics.] Academy of Sciences of the USSR. Vladivostok. (In Russian.)

Dragonetti, M 2007. Individuality in scops owl Otus scops vocalisations. Bioacoustics 16: 147-172.

Dreiss, A N, Antoniazza, S, Burri, R, Fumagalli, L, Sonnay, C, Frey, C, Goudet, J & Roulin, A 2011. Local adaptation and matching habitat choice in female barn owls with respect to melanic coloration. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 25: 103-114.

Eastham, A 1968. The avifauna of Gorham’s Cave. Gibraltar. Bulletin of the Institute of Archeology 7: 37-42.

Eastham, A 2012. The Magdalenians and Snowy Owls. P 238-243 in: Potapov, E & Sale, R, The Snowy Owl. London.

Ebels, E B 2002. Brown Fish Owl in the Western Palearctic. Dutch Birding 24: 157-161.

van Eijk, P 2013. Presumed second locality for Omani Owl. Dutch Birding 35: 387-388.

Eken, G 1997. Regular wintering by Scops Owls Otus scops in Turkey, at Havran Delta. Sandgrouse 19: 147.

Escarguel, G, Marandat, B & Legendre, S 1997. Sur l’âge numérique des faunes de mammifères du Paléogène d’Europe occidentale, en particulier celles de l’Eocène inférieur et moyen. P 443-460 in: Aguilar, J-P, Legendre, S & Michaux, J (editors), Actes du Congrès Biochrom ’97. Montpellier.

Evans, D L 1980. Vocalizations and territorial behavior of wintering Snowy Owls. American Birds 34: 748-749.

Exo, K-M 1984. Die akustische Unterscheidung von Steinkauzmännchen und –weibchen (Athene noctua). Journal für Ornithologie 125: 94-97.

Exo, K-M & Scherzinger, W 1989. Stimme und Lautrepertoire des Steinkauzes (Athene noctua): Beschreibung, Kontext und Lebensraum-anpassung. Ökologie der Vögel 11: 149-187.

Flint, P & Stewart, P 1992. The birds of Cyprus. British Ornithologists’ Union check-list 6. Tring.

Florit, X & Alcover, J A 1987. Els ocells del Pleistocè Superior de la Cova Nova (Capdepera, Mallorca). II fauna associada i discussió. Bolletí de la Societat d’Història Natural de les Balears 31: 33-44.

Forster, J R 1772. Descriptiones Avium Rariorum e Sinu Hudsonis. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society 62: 423-433..

Frey, H 1973. Zur Ökologie Nieder-Österreichischer Uhupopulationen. Diss Tierärztl Hochsch. Wien.

Fry, C H, Keith, S & Urban, E K 1988. Handbook of the birds of Africa 3. London.

Fuchs, J, Pons, J-M, Goodman, S M, Bretagnolle, V, Melo, M, Bowie, R C K, Currie, D, Safford, R, Virani, M Z, Thomsett, S, Hija, A, Cruaud, C & Pasquet, E 2008. Tracing the colonization history of the Indian Ocean scops-owls (Strigiformes: Otus) with further insight into the spatio-temporal origin of the Malagasy avifauna. BMC Evolutionary Biology 8: 197.

Galeotti, P 1998. Correlates of hoot rate and structure in male Tawny Owls Strix aluco: Implications for male rivalry and female mate choice. Journal of Avian Biology 29: 25-32.

Galeotti, P R, Appleby, B M & Redpath, S M 1996. Macro and microgeographical variations in the ‘hoot’ of Italian and English tawny owls (Strix aluco). Italian Journal of Zoology 63: 57-64.

Galeotti, P & Pavan, G 2008. Differential responses of territorial Tawny Owls Strix aluco to the hooting of neighbours and strangers. Ibis 135: 300-304.

Galeotti, P & Rubolini, D 2007. Head ornaments in owls: what are their functions? Journal of Avian Biology 38: 731-736.

Galeotti, P & Sacchi, R 2001. Turnover of territorial Scops Owl Otus scops as estimated by spectrographic analyses of male hoots. Journal of Avian Biology 32: 256-262.

Geniez, P & López-Jurado, L F 1998. Nouvelles observations ornithologiques aux Îles du Cap-Vert. Alauda 66: 307-311.

Glue, D E 2002. Little Owl Athene noctua. In: Wernham, C V, Toms, M P, Clark, G M et al (editors), The Migration Atlas: Movements of the birds of Britain and Ireland. London.

Glutz von Blotzheim, U N & Bauer, K M 1980. Handbuch der Vögel Mitteleuropas 9. Wiesbaden.

Guérin-Méneville, F E 1843. Oiseaux nouveaux découverts par MM. Ferret et Galinier pendant leur voyage en Abyssinie. Bubo cinerascens. Revue Zoologique par la Société Cuvierienne 6: 321.

Guerra, C, Bover, P & Alcover, J A 2012. A new species of extinct little owl from the Pleistocene of Mallorca (Balearic Islands). Journal of Ornithology 153: 347-354.

Hagemeijer, W J M & & Blair, M J 1997. The EBCC Atlas of European breeding birds. London.

Halder, R 2004. A sound guide to the birds of Bangladesh. CD and booklet.

Hambling, R 2008. Tawny owl calls and vocalizations. www.godsownclay.com/TawnyOwls/Calls/tawnyowlcalls1.html. Accessed on 10 April 2014, no longer available in 2021.

Hamdine, W, Bouzhemza, M, Doumandji, S-E, Poitevin, F & Thévenot, M 1999. Premières données sur le régime alimentaire de la Chouette hulotte (Strix aluco mauritanica) en Algérie. Ecologia Mediterranea 25: 111-123.

Hansson, L & Henttonen, H 1985. Gradients in density variations of small rodents: the importance of latitude and snow cover. Oecologia 67: 394-402.

Hardouin, L A, Reby, D, Bavoux, C, Burneleau, G & Bretagnolle, V 2007. Communication of male quality in owl hoots. The American Naturalist 169: 552-562.

Hardouin, L A, Bretagnolle, V, Tabel, P, Bavoux, C, Burneleau, G & Reby, D 2009. Acoustic cues to reproductive success in male owl hoots. Animal Behaviour 78: 907-913.

Harrop, A H J 2010. Records of Hawk Owls in Britain. British Birds 103: 276-283.

Harvancik, S 2009. Owls of Slovakia in pictures. CD and book. Zvolen.

Hausknecht, R, Jacobs, S, Müller, J, Zink, R, Frey, H, Solheim, R, Vrezec, A, Kristin, A, Mihok, J, Kergalve, I, Saurola, P & Kuehn, R 2014. Phylogeographic analysis and genetic cluster recogition for the conservation of Ural Owls (Strix uralensis) in Europe. Journal of Ornithology 155: 121-134.

Hawley, R G 1966. Observations on the Long-eared Owl. Sorby Record 2: 95-114.

Haynes, S, Jaarola, M & Searle, J B 2003. Phylogeography of the Common Vole (Microtus arvalis) with particular emphasis on the colonisation of the Orkney archipelago. Molecular Ecology 12: 951-956.

Hazevoet, C J 1995. The birds of the Cape Verde Islands. British Ornithologists’ Union check-list 13. Tring.

Heim de Balsac, H & Mayaud, N 1962. Les oiseaux du nord-ouest de l’Afrique. Paris.

Heinzel, H, Fitter, R & Parslow, J 1972. The birds of Britain and Europe with North Africa and the Middle East. London.

Hipkiss, T, Hörnfeldt, B, Lundmark, A & Norbäck, M 2002. Sex ratio and age structure of nomadic Tengmalm’s owls: a molecular approach. Journal of Avian Biology 33: 107-110.

Holmberg, T 1974. En studie av slagugglans Strix uralensis läten. Vår Vågelvärld 33: 140-146.

del Hoyo, J, Elliott, A & Sargatal, J (editors) 1999. Handbook of the birds of the world 5. Barcelona.

del Hoyo, J & Collar, N J 2014. Illustrated checklist of the birds of the world 1: non-passeriformes. Barcelona.

Horner, K O & Hubbard, J P 1982. An analysis of birds limed in spring at Paralimni, Cyprus. Cyprus Ornithological Society (1970) report 7: 54-104.

Hüe, F & Etchécopar, R D 1970. Les oiseaux du Proche et du Moyen Orient. Paris.

Huguet, P & Chappuis, C 2002. Bird sounds of Madagascar, Mayotte, Comoros, Seychelles, Réunion and Mauritius. 4 CDs and booklet.

Hull, J M, Englis, A, Medley, J R, Jepsen, E P, Duncan, J R, Ernest, H B & Keane, J J 2014. A new subspecies of Great Gray Owl (Strix nebulosa) in the Sierra Nevada of California. Journal of Raptor Research 48: 68-77.

Hume, A 1878. Asio butleri, Sp. Nov.? Stray Feathers 7: 316-318.

Hüni, M 1982. Exkursion der Ala in die Sudosttürkei, 3-17. April 1982. Ornithologische Beobachter 79 : 221-223.

Irby, L H 1895. The ornithology of the Strait of Gibraltar. Second edition. London.

Isenmann, P & Moali, A 2000. Birds of Algeria. Paris.

Jaume, D, McMinn, M & Alcover, J A 1993. Fossil birds from the Bujero del Silo, La Gomera (Canary Islands), with a description of a new species of quail (Galliformes: Phasianidae). Boletim do Museu Municipal do Funchal, Sup 2: 147-165.

Jennings, M C 2010. Atlas of the breeding birds of Arabia. Fauna of Arabia 25: 1-772.

Johnsen, A, Rindal, E, Ericson, P G P, Zuccon, D, Kerr, K C R, Stoeckle, M Y & Lifjeld, J T 2010. DNA barcoding of Scandinavian birds reveals divergent lineages in trans-Atlantic species. Journal of Ornithology 151: 565-578.

Jolly, D, Prentice, I C, Bonnefille, R, Ballouche, A, Bengo, M, Brenac, P, Buchet, G, Burney, D, Cazet, J-P, Cheddadi, R, Edorh, T, Elenga, H, Elmoutaki, S, Guiot, J, Laarif, F, Lamb, H, Lezine, A-M, Malet, J, Mbenza, M, Peyron, O, Reille, M, Reynaud-Farrera, I, Riollet, G, Ritchie, J C, Roche, E, Scott, L, Ssemmanda, I, Straka, H, Umer, M, Van Campo, E, Vilimumbalo, S, Vincens, A & Waller, M 1998. Biome reconstruction from pollen and plant macrofossil data for Africa and the Arabian peninsula at 0 and 6000 years. Journal of Biogeography 25: 1007-1027.

Joubert, H J 1943. Nest and eggs of the S. African Marsh Owl. Ostrich 14:42-44.

Keijl, G O & Sandee, H 1996. On occurrence and diet of the Marsh Owl Asio capensis in the Merja Zerga, northwest Morocco. Alauda 64: 451-453.

Kellomäki, E 1977. Food of the Pygmy Owl Glaucidium passerinum in the breeding season. Ornis Fennica 54: 1-29.

Kemp, A 1987. Owls of Southern Africa. Cape Town.

Kemp, J 1981. Breeding Long-eared Owls in West Norfolk. Norfolk Bird & Mammal Report 1980. Transactions of the Norfolk & Norwich Naturalists’ Society 25: 234-286.

Khaleghizadeh A, Scott, D A, Tohidifar, M, Musavi S B, Ghasemi M, Sehhatisabet M E, Ashoori A, Khani A, Bakhtiari P, Amini H, Roselaar C, Ayé R, Ullman M, Nezami B & Eskandari F 2011. Rare Birds in Iran in 1980−2010. Podoces 6: 1-48.

Kirwan, G M, Schweizer, M & Copete, J L 2015. Multiple lines of evidence confirm that Hume’s Owl Strix butleri (A. O. Hume, 1878) is two species, with description of an unnamed species (Aves: Non-Passeriformes: Strigidae). Zootaxa 3904: 28–50.

König, C 1968. Lautäußerungen von Rauhfußkauz (Aegolius funereus) und Sperlingskauz (Glaucidium passerinum). Vogelwelt, Beiheft 1: 115-138.

König, C 1970. Herbstbalz der Zwergohreule (Otus scops). Ornithologische Mitteilungen 22: 44-45.

König, L 1973. Das Aktionssystem der Zwergohreule Otus scops scops (Linné 1758). Journal of Comparative Ethology, Supplement 13: 1-124.

König, C, Weick, F & Becking, J-H 2008. Owls of the world. Second edition. London.

Konishi, M 1973. How the owl tracks its prey: experiments with trained barn owls reveal how their acute sense of hearing enables them to catch prey in the dark. American Scientist 61: 414-424.

Koopman, M E, McDonald, D B, Hayward, G D, Eldegard, K, Sonerud, G A & Sermach, S G 2005. Genetic similarity among Eurasian subspecies of boreal owls Aegolius funereus. Journal of Avian Biology 36: 179-183.

Korpimäki & Hakkarainen 2012. The Boreal Owl – ecology, behaviour and conservation of a forest-dwelling predator. Cambridge, UK.

Kuhk, R 1953. Lautäußerungen und jahreszeitliche Gesangstätigkeit des Rauhfußkauzes, Aegolius funereus (L.). Journal für Ornithologie 94: 83-93.

Kullberg, C 1995. Strategy of the Pygmy Owls while hunting avian and mammalian prey. Ornis Fennica 72: 72-78.

Laidler, D 2010. Spotted Eagle Owl growing up. Video uploaded on 20 November 2010. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2KPeM1uqSKk

Ławicki, Ł, Abramčuk, A V, Domashevsky, S V, Paal, U, Solheim, R, Chodkiewicz T & Woźniak, B 2013. Range extension of Great Grey Owl in Europe. Dutch Birding 35: 145-154.

Legge, W V 1880. A history of the birds of Ceylon. London.

Lerman, S B, Smith, J P & Atwood, J A 2006. Factors affecting the winter distribution of Striated Scops-Owl, (Otus brucei), in southern Israel. IV North American Ornithological Conference, Veracruz, Mexico. Poster.

Leshem, J 1981. The occurrence of Hume’s Tawny Owl in Israel and Sinai. Sandgrouse 2: 100-102.

Lindblad, J 1967. I ugglemarker. Book and gramophone record. Stockholm.

Lindén, A 2013. Identifying the songs of Eurasian Scops Owl and Eurasian Pygmy Owl. Caluta 4: 12-20.

Löfgren, O, Hörnfeldt, B & Carlsson, B-G 1986. Site tenacity and nomadism in Tengmalm’s Owl (Aegolius funereus (L.)) in relation to cyclic food production. Oecologia 69: 321-326.

López-Darias, M, Hernández, A & Hernández, J 2006. Búho Chico Asio otus in: Noticiario Ornitológico. Ardeola 53: 206.

Louchart, A 2011. Paleornithology, Bubo insularis and deletion of putative records of Brown Fish Owl in the western Mediterranean. Dutch Birding 33: 251-252.

Lundberg, A 1980. Vocalizations and courtship feeding of the Ural Owl Strix uralensis. Ornis Scandinavica 11: 65-70.

van Maanen, E & Cuyten, K 2012. In search of Carnivores at the “end of the world”. Report of a trip to Iran 7-16 April 2012. The Anatolian Leopard Foundation/Plan for the Land.

Magnin, G 1991. A record of the Brown Fish Owl Ketupa zeylonensis from Turkey. Sandgrouse 13: 42-44.

Marti, C D, Poole, A F & Bevier, L R 2005. Barn Owl (Tyto alba). The birds of North America online (bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/001). Ithaca.

Martins, R P & Hirschfeld, E 1998. Comments on the limits of the Western Palearctic in Iran and the Arabian Peninsula. Sandgrouse 20: 108-34.

Mebs, T & Scherzinger, W 2004. Uilen van Europa. Baarn.

Megalli, M, Moldovan, S & Gilbert, H 2011. Trip report: Sinai, Red Sea, Oases, North Coast Oct. 4-19, 2011.

Meinertzhagen, R 1930. Nicoll’s Birds of Egypt. London.

Mendelsson, H, Yom-Tov, Y & Safriel, U 1975. Hume’s Tawny Owl Strix butleri in the Judean, Negev and Sinai Deserts. Ibis 117: 110-111.

Mikkola, H 1983. Owls of Europe. Calton.

Mikkola, H 2012. Owls of the world, a photographic guide. London.

Mikkola, H & Sieradzki, A 2012. Early history of the Great Gray Owl in the New and Old World. Ontario Birds 30: 26-29.

Miller, A H 1934. The vocal apparatus of some North American owls. Condor 36: 204-213.

Milza, J-C 1997. Athene angelis n. sp. (Aves, Strigiformes), nouvelle espèce endémique insulaire éteinte du Pléistocène moyen et supérieur de Corse (France). Comptes Rendus de l’Academie des Sciences de Paris, série IIa 324: 677-684.

Moreau, R E 1972. The Palearctic-African bird migration systems. London.

Moreno, J M 2000. Cantos y reclamos de las aves de Canarias. 2 CDs and book. Santa Cruz de Tenerife.

Mori, E, Menchetti, M & Ferretti, F 2014. Seasonal and environmental influences on the calling behaviour of Eurasian Scops Owls. Bird Study 61: 277-281.

Mourer-Chauviré, C 1975. Les oiseaux du Pléistocène moyen et supérieur de France. Documents du Laboratoire de Géologie de la Faculté de Sciences de Lyon 64: 1-624.

Mourer-Chauviré, C 1987. Les Strigiformes (Aves) des Phosphorites du Quercy (France): Systématique, biostratigraphie et paléobiogéographie. In: Mourer-Chauviré, C (editor), L’évolution des Oiseaux d’après le Témoignage des Fossiles. Documents des Laboratoires de Géologie de Lyon 99: 89-135.

Mourer-Chauviré, C, Alcover, J A, Moya, S & Pons, J 1980. Une nouvelle forme insulaire d’effraie géante, Tyto balearica n. sp., (Aves, Strigiformes), du Plio-Pléistocène des Balears. Géobios 13: 803-811.

Mourer-Chauviré, C & Geraads, D 2010. The Upper Pliocene Avifauna of Ahl al Oughlam, Morocco. Systematics and Biogeography. Records of the Australian Museum 62: 157-184.

Mourer-Chauviré, C, Salotti, M, Pereira, É, Quinif, Y, Courtois, J-Y, Dubois, J-N & La Milza, J C. Athene angelis n. sp. (Aves, Strigiformes), nouvelle espèce endémique insulaire éteinte du Pléistocène moyen et supérieur de Corse (France). Comptes rendus de l’Académie des sciences. Série 2, Sciences de la terre et des planètes, Paris, v 324, no 8, 1997, p 677-684.

Mourer-Chauviré, C & Sanchez Marco, A 1988. Présence de Tyto balearica (Aves, Strigiformes) dans des gisements continentaux du Pliocène de France et d’Espagne. Géobios 21: 639-644.

Mundkur, T 1986. Occurrence of the Pallid Scops Owl Otus brucei (Hume) in Rajkot, Gujarat. Newsletter for Birdwatchers 26: 10-11.

de Naurois, R 1982. Le statut de l’Effraie de l’archipel du Cap Vert Tyto alba detorta. Rivista Italiana di Ornitologia 52: 154-166.

Nero, R W 1982. The Great Gray Owl, phantom of the Northern Forest. Washington.

van Nieuwenhuyse, D, Génot, J-C & Johnson, D H 2008. The Little Owl. Conservation, Ecology and Behavior of Athene noctua. Cambridge, UK.

Nijman, V & Aliabadian, M 2013. DNA Barcoding as a tool for elucidating species delineation in wide-ranging species as illustrated by owls (Tytonidae and Strigidae). Zoological Science 30: 1005-1009.

Nybo, J O & Sonerud, G A 1990. Seasonal changes in the diet of Hawk Owls Surnia ulula: the importance of snow cover. Ornis Fennica 67: 45-51.

O’Reilly, R 2000. Trip report: Oman – 22 September to 5 October 2000.

Olson, S L 2012. A new species of small owl of the genus Aegolius (Aves: Strigidae) from Quaternary deposits on Bermuda. Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington 125: 97-105.

Olsson, V 1979. Studies on a population of Eagle Owls Bubo bubo (L.) in southeast Sweden. Viltrevy 11: 1-99.

Omote, K, Nishida, C, Dick, M H & Masuda, R 2013. Limited phylogenetic distribution of a long tandem-repeat cluster in the mitochondrial control region in Bubo (Aves, Strigidae) and cluster variation in Blakiston’s fish owl (Bubo blakistoni). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 66: 889-897.

Ottens, G & Jonker, M 2010. Ruigpootuilen in Drenthe in 2008-2010: terug van weggeweest? Uilen 1: 80-89.

Parmalee, P W & Klippel, W E 1982. Evidence of a Boreal Avifauna in Middle Tennessee during the Late Pleistocene. Auk 99: 365-368.

Pavia, M 2004. A new large barn owl (Aves, Strigiformes, Tytonidae) from the Middle Pleistocene of Sicily, Italy, and its taphonomical significance. Geobios 37: 631-641.

Pavia, M 2008. The evolution dynamics of the Strigiformes in the Mediterranean islands with the description of Aegolius martae n. sp. (Aves, Strigidae). Quaternary International 182: 80-89.

Pavia, M & Mourer-Chauviré, C 2002. An overview of the genus Athene in the Pleistocene of the Mediterranean islands, with the description of Athene trinacriae n. sp. (Aves: Strigidae). Proceedings of the 5th Symposium of the Society of Paleontology and Evolution 13-27.

Payne, R S & Drury, W H 1958. Marksman of the darkness. Natural History 67: 316-323.

Pellegrino, I, Negri, A, Cucco, M, Mucci, N, Pavia, M, Sálek, M, Boano, G & Randi, E 2014. Phylogeography and Pleistocene refugia of the Little Owl Athene noctua inferred from mtDNA sequencing. Ibis 156: 639-657.

Pelz, P 2008. Europas Ugglor / Owls of Europe. CD and booklet.

Penteriani, V 2002. Variation in the function of Eagle Owl vocal behaviour: territorial defence and intra-pair communication? Ethology, Ecology & Evolution 14: 275-281.

Penteriani, V, Alonso-Alvarez, C, Delgado, M del M, Sergio, F & Ferrer, M 2006. Brightness variability in the white badge of the eagle owl Bubo bubo. Journal of Avian Biology 37: 110-116.

Penteriani, V, Delgado, M del M, Alonso-Alvarez, C & Sergio, F 2007. The importance of visual cues for nocturnal species: eagle owls signal by badge brightness. Behavioral Ecology 18: 143-147.

Penteriani, V, Delgado, M del M, Campioni, L & Lourenço, R 2010. Moonlight makes owls more chatty. PLoS One 5: 1-5.

Penteriani, V & Delgado, M del M 2009. The dusk chorus from an owl perspective: Eagle Owls vocalize when their white throat badge contrasts most. PLoS ONE 4: 1-4.

Penteriani, V, Delgado, M del M, Stigliano, R, Campioni, L & Sánchez Medina, M 2014. Owl dusk chorus is related to individual and nest site quality. Ibis 156: 892-895.

Polakowski, M, Broniszewska, M & Skierczyński, M 2008. Sex and age composition during autumn migration of Pygmy Owl Glaucidium passerinum in Central Sweden in 2005. Ornis Svecica 18: 82-86.

Pons, J-M, Kirwan, G M, Porter, R F & Fuchs, J 2013. A reappraisal of the systematic affinities of Socotran, Arabian and East African scops owls (Otus, Strigidae) using a combination of molecular, biometric and acoustic data. Ibis 155: 518-533.

Potapov, E & Sale, R 2012. The Snowy Owl. London.

Pozdnyakov, V I & Sofronov, Y N 2005. [Snowy Owl in the Lena Delta.] P 36-40 in: Volkov, S, Mozorov, V & Sharikov, A (editors), [Owls of Northern Eurasia]. Moscow. (In Russian with English summary.)

Pukinskiy, Y B 1974. Blakiston’s Fish Owl vocal reactions. Vestnik Leningradskogo Universityrsiteta 3: 35-39. (In Russian with English summary.)

Pukinskiy, Y B 1993. Blakiston’s Fish Owl Ketupa blakistoni. P 290-302 in V D Ilichev (editor), Birds of Russia and adjacent regions. Moscow. (In Russian.)

Rando, J C, Alcover, J A, Michaux, J, Hutterer, R & Navarro, J F 2011. Late-Holocene asynchronous extinction of endemic mammals on the eastern Canary Islands. The Holocene 22: 801-808.

Rando, J C, Alcover, J A, Navarro, J F, Michaux, J & Hutterer, R 2011. Poniendo fechas a una catástrofe: 14C, cronologías y causas de la extinción de vertebrados en Canarias. El Indiferente 21: 6-15.

Rando, J C, Alcover, J A, Olson, S L & Pieper, H 2013. A new species of extinct scops owl (Aves: Strigiformes: Strigidae: Otus) from São Miguel Island (Azores Archipelago, North Atlantic Ocean). Zootaxa 3647: 343-357.

Rando, J C, Pieper, H, Alcover, J A & Olson S L 2012. A new species of extinct fossil scops owl (Aves: Strigiformes: Strigidae: Otus) from the Archipelago of Madeira. Zootaxa 3182: 29-42.

Rasmussen, P C & Anderton, J C 2005. Birds of South Asia: the Ripley guide 1 & 2. Barcelona.

Redpath, S M, Appleby, B M & Petty, S J 2000. Do male hoots betray parasite loads in Tawny Owls? Journal of Avian Biology 31: 457-462.

Rifai, L B, Al-Melhim, W N, Gharaibeh, B M & Amr, Z S 2000. The diet of the Desert Eagle Owl, Bubo bubo ascalaphus, in the Eastern Desert of Jordan. Journal of Arid Environments 44: 369–372.

Robb, M 2009. Review: Indian bird sounds by C Chappuis, F Deroussen & D Warakagoda 2008. Dutch Birding 31: 368-369.

Robb, M R, van den Berg, A B & Constantine, M 2013. A new species of Strix owl from Oman. Dutch Birding 35: 275-310.

Roberts, T J 1991. The birds of Pakistan 1. Non-Passeriformes. Karachi.

Roberts, T J & King, B 1986. Vocalizations of the Owls of the Genus Otus in Pakistan. Ornis Scandinavica 17: 299-305.

Robertson, G & Gilchrist, H 2003. Wintering Snowy Owls feed on sea ducks in the Belcher Islands, Nunavut, Canada. Journal of Raptor Research 37: 164-166.

Rognan, C B 2007. Bioacoustic techniques to monitor Great Gray Owls (Strix nebulosa) in the Sierra Nevada. MA thesis, Humboldt State University.

Rohner, C, Smith, J N M, Stroman, J & Joyce, M, Doyle, F I & Boonstra, R 1995. Northern Hawk-Owls in the Nearctic boreal forest: prey selection and population consequences of multiple prey cycles. The Condor 97: 208-220.

Le Roi, O 1923. Die Ornis der Sinai-Halbinsel. Journal für Ornithologie 71: 28-95.

Rosmay, C D & Roselaar, C S 2013. American Hawk-Owl caught off Las Palmas, Gran Canaria, Canary Islands, in October 1924. Dutch Birding 35: 1-6.

Roselaar, C S 2006. The boundaries of the Palearctic region. British Birds 99: 602-618.

Rothschild, W & Hartert, E 1910. Bubo bubo interpositus subspec. nov. Novitates Zoologicae 17: 111.

Roulin, A 2004. Covariation between plumage colour polymorphism and diet in the Barn Owl Tyto alba. Ibis 146: 509-517.

Roulin, A, Kölliker, M & Richner, H 2000. Barn owl (Tyto alba) siblings vocally negotiate resources. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 267: 459-463.

Saint-Girons, M C, Thévenot, M & Thouy, P 1974. Le regime alimentaire de la Chouette Effraie (Tyto alba) et du Grand-Duc Ascalaphe (Bubo bubo ascalaphus) dans quelques localités marocains. C.N.R.S. II, Travaux R C P 249: 257-265.

Sándor, A D & Orbán, Z 2008. Food of the Desert Eagle Owl, Bubo ascalaphus, in Siwa Oasis, Western Desert, Egypt. Zoology in the Middle East 43: 5-7.

Sánchez Marco, A 2004. Avian zoogeographical patterns during the Quaternary in the Mediterranean region and paleaoclimatic interpretation. Ardeola 51: 91-132.

Sangster, G 2013. Integrative taxonomy of birds: Studies into the nature, origin and delimitation of species. Doctoral thesis, Stockholm University.

Sangster, G, King, B F, Verbelen, P & Trainor, C R 2013. A new species of the genus Otus (Aves: Strigidae) from Lombok, Indonesia. PLOS one 8: 1-13.

Sargeant, D E, Eriksen, H & Eriksen, J 2008. Birdwatching guide to Oman. Second edition. Muscat.

Saurola, P 1995. Suomen Pöllöt. CD and book. Helsinki.

Saurola, P 2002. Natal dispersal distances of Finnish owls: results from ringing. In: Newton, I, Kavanagh, R, Olsen, J & Taylor, I (editors), Ecology and Conservation of Owls. Collingwood.

Savigny, N J C L 1809. Description d’Égypte 23: 295. Paris.

sccontaindergarden 2012. Walks With Birds – Desert Eagle Owl. Online video, accessed on 16 October 2013. www.youtube.com/watch?v=BTcsZLIo3mQ

Schaanning, H T L 1907. Østfinmarkens fuglefauna. Bergens Museum Aarbog 8: 1-98.

Scherzinger, W 1970. Zum Aktionssystem des Sperlingkauzes (Glaucidium passerinum, L.). Zoologica 118: 1-120.

Scherzinger, W 1974a. Die Jugendentwicklung des Uhus (Bubo bubo) mit Vergleichen zu der von Schneeeule (Nyctea scandiaca) und Sumpfohreule (Asio flammeus). Bonner Zoologische Beiträge 25: 123-147.

Scherzinger, W 1974b. Zur Ethologie und Jugendentwicklung der Schnee-Eule (Nyctea scandiaca) nach Beobachtungen in Gefangenschaft. Journal für Ornithologie 115: 8-49.

Scherzinger, W 1980. Zur Ethologie der Fortpflanzung und Jugendentwicklung des Habichtskauzes (Strix uralensis) mit vergleich zum Waldkauz (Strix aluco). Bonner Zoologische Monographien 15.

Scherzinger, W 2005. Remarks on Sichaun Wood Owl Strix uralensis davidi from observations in south-west China. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club 125: 275-286.

Scherzinger, W & Fang, Y 2006. Field Observations of the Sichuan Wood Owl Strix uralensis davidi in western China. Acrocephalus 27: 3-12.

Schnurre, O 1936. Zur Biologie des deutschen Uhus. Beiträge zur Fortpflanzungsbiologie der Vögel 12: 1-12, 54-69.

Schwerdtfeger, O 1991. Altersstruktur und Populationsdynamik beim Rauhfußkauz (Aegolius funereus). Populationsoekologie Greifvogel- und Eulenarten 2. Wissenschaftliche Beitraege Universitaet Halle: 493-506.

Scott, D 1997. The Long-eared Owl. London.

Sharpe, R B 1886. Bubo milesi sp. n. Ibis 28: 163-164.

Shashidara, M 1989. Comment on Brown Fish Owls. Newsletter for Birdwatchers 29: 10.

Shehab, A H & Ciach, M 2008. Diet Composition of the Pharaoh Eagle Owl, Bubo ascalaphus, in Azraq Nature Reserve, Jordan. Turkish Journal of Zoology 32: 65-69.

Shenbrot, G, Krasnov, B & Burdelov, S 2010. Long-term study of population dynamics and habitat selection of rodents in the Negev Desert. Journal of Mammalogy 91: 776-786.

Shepard, P 1978. Thinking animals. New York.

Shirihai, H, Dovrat, E, Christie, D A, Harris, A & Cottridge, D 1996. The birds of Israel. London.

Siverio, F 2008. Lechuza común Tyto alba. In: Lorenzo, J A (editor), Atlas de las aves nidificantes en el Archipiélago Canario (1997-2003). Madrid.

Siverio, F, Barone, R, Siverio, M, Trujillo, D & Ramos, J J 1999. Response to conspecific calls, distribution and habitat of Tyto alba (Aves: Tytonidae) on La Gomera, Canary Islands. Revista de la Academia Canaria de Ciencias 11: 213-222.

Siverio, F, Trujillo, D & Ramos, J J 2001. Notes on the distribution of the Madeiran Barn Owl Tyto alba schmitzi (Aves: Tytonidae). Revista de la Academia Canaria de Ciencias 13: 199-205.

Siverio, F, Mateo, J A & López-Jurado L F 2007. On the presence and biology of the Barn Owl Tyto alba detorta on Santa Luzia, Cape Verde Islands. Alauda 75: 91-93.

Smith, N, Bates, K & Fuller, M 2012. Wintering Snowy Owls at Logan International Airport. P 208-210 in: Potapov, E & Sale, R 2012, The Snowy Owl. London.

Smith, V W & Killick-Kendrick, R 1964. Notes on the breeding of the Marsh Owl Asio capensis in Northern Nigeria. Ibis 106: 119-123.

Snow, D W & Perrins, C M 1998. The birds of the Western Palearctic. Concise edition. Vol 1. Non-passerines. Oxford.

Solheim, R, Jacobsen, K O & Øien, I 2008. Snøuglenes vandringer: Ett år, tre ugler og ny kunnskap. Vår Fuglefauna 31: 102-109.

Solheim, R, Jacobsen, K O, Øien, I & Aarvak, T 2009. Snøuglenes vandringer fortsetter. Vår Fuglefauna 32: 172-176.

Sonerud, G A 1994. Haukugle Surnia ulula.

Sonerud, G A 1997. Hawk Owls in Fennoscandia: population fluctuations, effects of modern forestry, and recommendations on improving foraging habitats. Journal of Raptor Research 31: 167-174.

Sorace, A 1987. Note sul canto territoriale del Barbagianni, Tyto alba. Rivista Italiana di Ornitologia 57: 144-145.

Sorbi, S 2013. Découverte de la Chevêchette d’Europe Glaucidium passerinum en Belgique et suivi d’une tentative de nidification. Aves 50: 2-8.

Stefansson, O 1997. Nordanskogans vagabond. Lappugglan (Strix nebulosa lapponica). Boden.

Stefansson, O 2013. Nordanskogans vagabond. Lappugglan (Strix nebulosa lapponica). Supplement nr 4. Boden.

Streseman, E 1943. Ueberblick über die Vögel Kretas und den Vogelzug in der Aegaeis. Journal für Ornithologie 91: 448-514.

Sutton, G M 1932. The birds of Southampton Island. Memoirs of the Carnegie Museum 12 (part 11, sec 2): 3-267.

Svensson, L, Grant, P J, Mullarney, K & Zetterström, D 2009. Collins bird guide. Second edition. London.

Taylor, I 1994. Barn owls. Predator-prey relationships and conservation. Cambridge, UK.

Temminck, C J 1821, Strix africana. In: Temminck, C J & Laugier de Chartrouse, M, Nouveau recueil de planches coloriées d’oiseaux, livr 9, pl 50. Paris.

Thévenot, M 2006. Aperçu du régime alimentaire du Grand-duc d’Afrique du Nord Bubo ascalaphus à Tata, Moyen Draa. Go-South Bulletin 3: 28-30.

Thorstrom, R, Hart, J & Watson, R T 2007. New record, ranging behaviour, vocalization and food of the Madagascar Red Owl Tyto soumagnei. Ibis 139: 477-481.

Tristram, H B 1879. Letter to the editor: Asio butleri and Caprimulgus tamaricis. Stray feathers 8: 416-417.

Tulloch, R J 1968. Snowy Owls breeding in Shetland in 1967. British Birds 61: 119-132.

Tyrberg, T 1998. Pleistocene birds of the Palearctic: a catalogue. Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Tyrberg, T 2008. Pleistocene birds of the Palearctic, online supplement. web.telia.com/~u11502098/pleistocene.html. Accessed on 8 February 2013.

Vaurie, C 1960. Systematic Notes on Palearctic Birds, no 41 Strigidae: The genus Bubo. American Museum Novitates 2000: 1-31.

Vein, D & Thévenot, M 1978. Etude sur le Hibou grand-duc Bubo bubo ascalaphus dans le Moyen-Atlas marocain. Nos Oiseaux 34: 347-351.

Voous, K H 1950. On the distributional and genetical origin of the intermediate populations of the Barn owl (Tyto alba) in Europe. In: Jordans, A & Peus, F, Syllegomena Biologica, Festschrift zum 80. Geburtstage von Herrn Pastor Dr Med H C Otto Kleinschmidt. Wittenburg.

Voous, K H 1988. Owls of the Northern Hemisphere. London.

Vrezec, A 2009. Melanism and plumage variation in macroura Ural Owl. Dutch Birding 31: 159-170.

Vyn, G 2006. Voices of North American owls. 2 CDs and booklet. Ithaca.

Wahlstedt, J 1969. Jakt, matning och läten hos lappuggla Strix nebulosa. Vår Fågelvärld 28: 89-101.

Warakagoda, D 1997. The birds sounds of Sri Lanka. An identification guide. 2 CDs and booklet. Nugegoda.

Watson, A 1957. The behaviour, breeding and food-ecology of the Snowy Owl Nyctea scandiaca. Ibis 99: 419–462.

Weesie, P D M 1982. A Pleistocene endemic island form within the genus Athene: Athene cretensis n. sp. (Aves, Strigiformes) from Crete. Proceedings of the Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie Wetenschappen, Series B 85: 323-336.

Weesie, P D M 1988. The Quaternary avifauna of Crete, Greece. Palaeovertebrata 18: 1-94.

Weick, F 2006. Owls (Strigiformes). Annotated and Illustrated Checklist. Berlin.

Weir, J T & Schluter, D 2008. Calibrating the avian molecular clock. Molecular Ecology 17: 2321-2328.

Wendland, V 1957. Aufziechnungen über Brutbiologie und Verhalten der Waldohreule (Asio otus). Journal für Ornithologie 98: 241-261.

Wendland, V 1963. Fünfjährige Beobachtungen an einer Population des Waldkauzes (Strix aluco) im Berliner Grunewald. Journal für Ornithologie 104: 23-57.

Whaley, D 1991. Scops Owl. Cyprus Ornithological Society 1957. Newsletter 2/91: 3.

Wiesner, J 1992. Dismigration und Verbreitung des Sperlingskauzes (Glaucidium passerinum L.) in Thüringen. Naturschutzreport/Jena 4: 62-66.

de Wijs, R 2009. De meerkoetroep van de…… www.home.zonnet.nl/myotis/uilkoet.htm. Accessed in 2014, no longer available in 2021.

Wink, M 2008. Phylogenetic and phylogeographic relationships. In: van Nieuwenhuyse, D, Génot, J-C & Johnson, D H, The Little Owl. Conservation, Ecology and Behavior of Athene noctua. Cambridge.

Wink, M, El-Sayed, A-A, Sauer-Gürth, H & Gonzalez, J 2009. Molecular phylogeny of owls (Strigiformes) inferred from DNA sequences of the mitochondrial cytochrome b and the nuclear RAG-1 gene. In: Johnson, D H, Nieuwenhuyse, D & Duncan, J R (editors), Proceedings of the Fourth World Owl Conference October-November 2007, Groningen, The Netherlands. Ardea 97: 581-591.

Wink, M & Heidrich, P 1999. Molecular phylogeny and systematics of owls (Strigiformes). In: König, C, Weick, F & Becking, J-H, Owls of the world. Robertsbridge.

Wink, M, Heidrich, P, Sauer-Gürth, H, Elsayed, A-A & Gonzalez, J 2008. Molecular phylogeny and systematics of owls (Strigiformes). In: König, C, Weick, F & Becking, J-H (editors), Owls of the world, second edition. London.

Witherby, H F 1905. Surnium aluco mauritanicum, n. subsp. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club 15: 36-37.

Woods, R W & Woods, A 1997. Atlas of breeding birds of the Falkland Islands. Oswestry.

Yalden, D 1999. The history of British mammals. London.

Yalden, D W & Albarella, U 2009. The history of British birds. Oxford.

Yöntem, O 2007. An observation of Brown Fish Owl Ketupa zeylonensis in Turkey. Sandgrouse 29: 94-95.

Zarudny, N A 1905. Zwei ornithologische Neuheiten aus West-Persien. Ornithologisches Jahrbuch 16: 141–142.