Nocturnal autumn migration in Dorset, England, and southern Portugal

Magnus Robb, Nick Hopper, Paul Morton & The Sound Approach

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana is not an easy migrant to observe in Britain. Most birders would be delighted to find just one during any given autumn. The majority of records come from well-watched migration hotspots in early autumn, especially on the eastern and southern coasts of England. These days it is very unusual for any site to host more than one on the same day. According to the Dorset Bird Reports, the annual county total in recent years has ranged between 3-9 birds (2008-2013). Our all-night sound recording of nocturnal migration has started to paint quite a different picture. In August and September 2016, we detected Ortolan a total of 31 times at two sites in Dorset, England: Poole Old Town centre and Portland Bill. Most of these were likely to have involved different individual birds, except perhaps during two nights where there may have been some repeat detections from potentially disoriented birds. What does seem clear however is that Ortolan is a more regular visitor than we had previously thought.

This study explains how we reached such a conclusion. We have divided it into two parts. The first is about identification and how and where we became familiar with Ortolan Bunting calls. When analysed, recordings of migrants during the day turned out to contain eight distinct call-types, six or possibly seven of which we have also recorded during the night. We give many examples from both night and day, and also of potential confusion species. The second part will tell the story of each author’s listening station, document night migration of Ortolans at each one, and consider the differing amounts of information in recordings, as well as the problem of assessing the number of individuals involved. We will conclude part 2 by asking why Ortolan should be so prominent among nocturnal migrants despite being so difficult to detect during the day, and sharing with you our astonishment at this phenomenon.

Ortolan night and day – identifying them by call

Of the three authors, MR has been recording Ortolan Bunting calls for longest, after developing a passion for sound identification of passing migrants while living in the Netherlands in the late 1990s and early 2000s. In the low countries, there is a tradition of birders visiting migration watchpoints, especially along the North Sea coast. At these points, observers watch and listen to autumn migration on a scale that can often be very impressive. The main focus here is on passerines, unlike famous migration bottlenecks such as the Strait of Gibraltar, or Eilat in southern Israel, where the focus is on soaring birds. In recent decades the popularity of migration counting in the Netherlands rose rapidly, as a quick look at the Dutch-founded international website trektellen.nl shows. On a typical October day in 2016 around 50 Dutch watchpoints were entering their counts on this website.

Anyone visiting such a migration watchpoint for the first time is likely to be impressed by the ability of experienced observers to name tiny dots passing by, largely based on their calls, and many will want to learn how to do the same. When MR started, he sound recorded most of the calls he was hearing, something that virtually nobody else was doing at the time. He soon built up a library of migrant calls, comparing them with published recordings and his own ones of birds not actually migrating, in order to make their identification as secure as possible. In 2000, MR co-founded the Sound Approach and these recordings became part of the Sound Approach collection.

In the Netherlands, Ortolan Bunting is a regular migrant passing in very small numbers. Under the right weather conditions, it is not unusual to hear more than one passing during a morning’s migration; 10 sites have had counts in double figures, and the national day record stands at 47 (De Nolle near Vlissingen, Zeeland, 7 September 1992). So with patience, it is possible to build up experience of Ortolan in migration flight. It is more difficult to find them foraging during the day but when MR did, he recorded them extensively, as a way of checking that the birds seen less well during migration flights had been correctly identified. In the meantime he and other members of the Sound Approach team recorded Ortolan in many other parts of its range, both during the breeding and migration periods.

In 2009, MR moved to Portugal, where he was disappointed to find that passerine migration observable by day was on a smaller scale than in the Netherlands. When parenthood also made him less free to travel to migration hotspots, he tried his luck with nocturnal migration in his back yard instead. This soon became a new obsession when he realised that surprising numbers of Ortolan Buntings were flying over his house on early autumn nights. Up to October 2016, MR has retained 106 recordings of Ortolan in nocturnal migration, most of them over his house in Cabriz, Sintra, but also at various other sites.

In Portugal, Ortolan Bunting is more numerous in autumn than in the Netherlands. Besides being a locally common breeder in upland terrain in the northern half of Iberia, a large part of the European breeding population passes through the peninsula in autumn. Still, most birders would be delighted to encounter an Ortolan during a morning’s birding in autumn and few would suspect how many are passing at night.

In August 2015, PM showed MR a mystery call he had recorded one night over his garden in Lytchett Matravers, Dorset, and MR immediately recognised it as an Ortolan. PM recorded another individual a month later from the same location, and with both NH and PM detecting them in 2016 from newly set up listening stations, the Dorset total of night migrating Ortolan recordings now stands at 33. We will explain more about the circumstances of these recordings in part 2, but first here is how we are identifying these birds as Ortolans.

Ortolan Buntings usually give more than one type of flight call

Ortolan Buntings use a surprising variety of calls during migration flights. One of their most peculiar characteristics is the way they deliver these calls, especially when undertaking longer flights. The calls are delivered as a ‘medley ‘of different types, often at fairly regular intervals. A more varied diurnal sequence might be plik…. plik…. plukpluk… tslew… tslew… pluk… tew… tew… plik… At night the gaps between calls are longer, sometimes 10–20 seconds, but the call types used in the dark are derived from exactly the same set used during the day.

When an Ortolan flies past on migration, it may be audible for 30 seconds or longer, depending on how soon it is picked up, whether special listening equipment is being used to amplify the sound, and how quiet the surroundings are. On one occasion in the Netherlands, a friend phoned MR from 1 km to the north and told him a day migrating Ortolan was on the way. Knowing which direction to aim, he picked it up with his Telinga parabolic microphone nearly a minute before it arrived. Listen to it approaching gradually, in the company of migrating yellow wagtails Motacilla, Meadow Pipits Anthus pratensis, Dunnocks Prunella modularis and a Common Reed Bunting E schoeniclus. We have only excluded the first 10 seconds, where you would struggle to hear the Ortolan. Most of the calls here could be described as plik or pluk.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, IJmuiden, Noord-Holland, Netherlands, 09:46, 10 September 2006. One migrating along the Dutch coast. Background: Meadow Pipit Anthus pratensis, yellow wagtail Motacilla, Dunnock Prunella modularis and Common Reed Bunting Emberiza schoeniclus. 060910.MR.94605.11

We have classified flight calls of Ortolan Bunting into eight types, all of which we have recognised in more than one individual. Five are common (four of these also at night) and three are rare. Here is a brief summary. Click on the name of each call to read about it in detail, listen to both day time and night time examples, and also to other species that sound similar.

| Plik | v common | day & night | fairly consistent | arch shaped, narrow frequency range |

| Pluk | v common | day only | consistent | low frequency, sharply rising |

| Tew | common | day & night | more variable | descending, steepest at top, monosyllabic |

| Tslew | common | day & night | more variable | descending, distinctly disyllabic |

| Tsrp | common | day & night | very variable | single pitch, fairly high, hint of roughness |

| Puw | rare | day & night | fairly consistent | low, fairly level, bullfinch-like |

| Tup | rare | day & night | fairly consistent | low, descending, chaffinch-like |

| Vin | v rare | day & night | fairly consistent | single pitch, low, brief, nasal |

Five call-types commonly heard from migrants

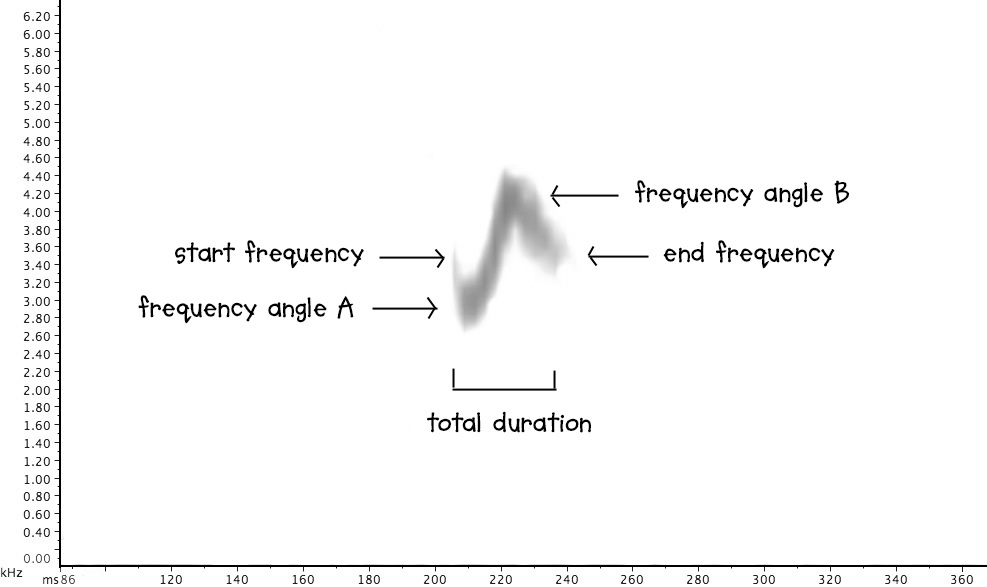

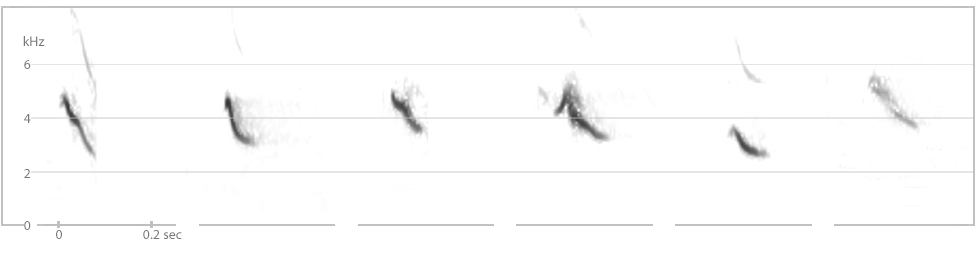

Plik is the commonest call of migrating Ortolan Buntings both day and night. It is distinctive; nothing else sounds quite like it. While there is considerable variation in pitch the shape is remarkably consistent. What all plik calls have in common is their short duration and narrow frequency range, making the call sound to human ears as if it has a single pitch, not rising or falling. In sonagrams, however, it appears as an arched shape with mean peak frequency of 4.4 kHz and a mean total duration of 35 mS (38 mS in our nocturnal examples). For a table of measurements scroll down. The call starts with a steep descending line of variable length and strength. Where this ends, it forms an acute ‘angle’ with the arch to its right. The rising ‘left side’ of the arch – a fairly straight line sloping up to the right – is the call’s most prominent – a more gentle slope descends to a greater or lesser degree, forming its right side. The first angle is always sharp, and the second may be sharp or more rounded. Listen to an example of a diurnal call sequence with several plik calls. Below it is a sonagram and corresponding sound file showing six variations of this call type recorded during the day.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, Cabo Espichel, Setubal, Portugal, 08:02, 17 September 2010 (Magnus Robb). Several plik calls in flight.

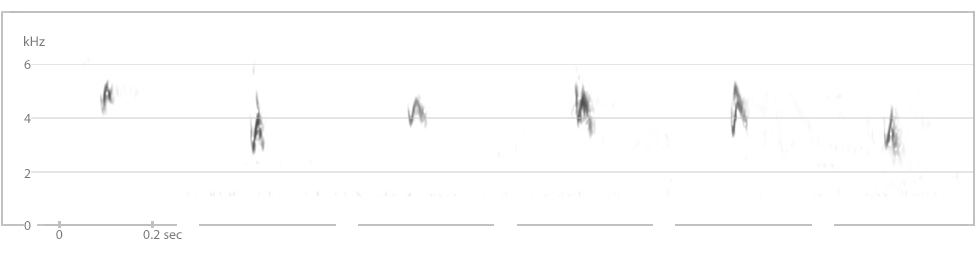

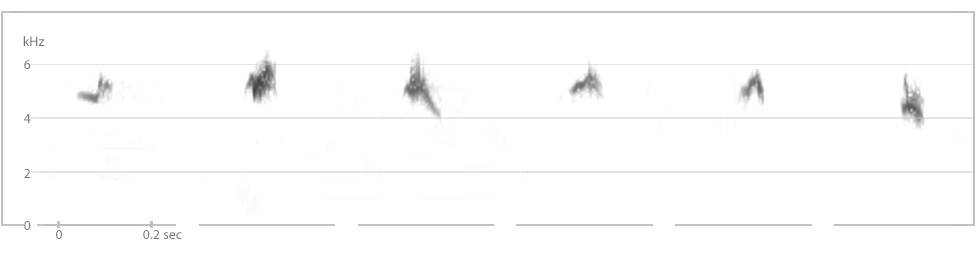

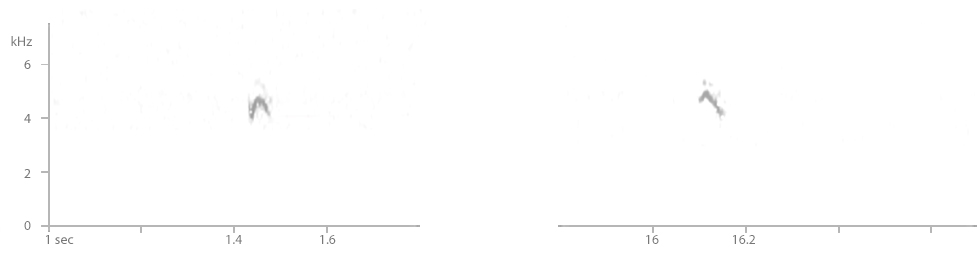

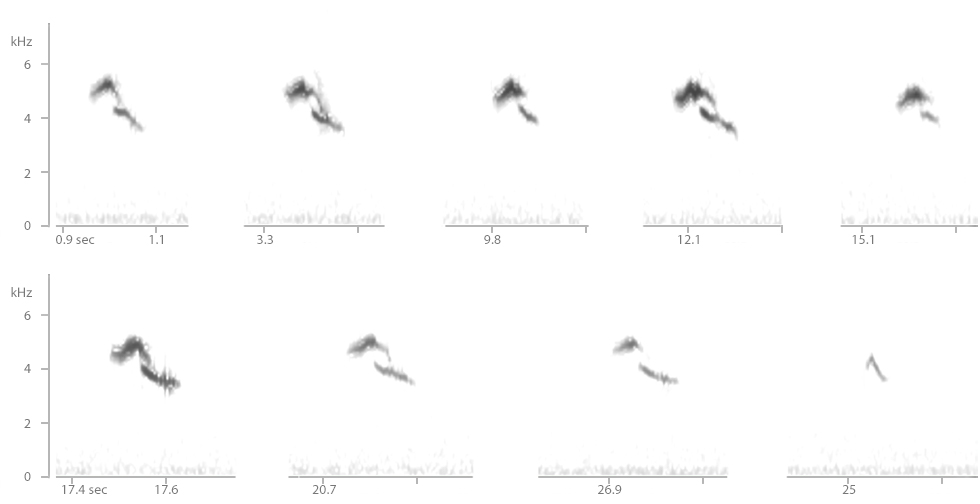

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana. Six variations of plik calls recorded by day. 1) Cabo Espichel, Setúbal, Portugal, 08:02, 17 September 2010 (Magnus Robb) 2) Sagres, Vila de Bispo, Portugal, 08:22, 17 September 2008 (Magnus Robb) 3) Ponta de Erva, Vila Franca de Xira, Portugal, 07:55, 22 September 2010 (Magnus Robb) 4) Vedi, Ararat, Armenia, 15:37, 14 May 2011 (Magnus Robb) 5) Planalto de Mourela, Montalegre, Portugal, 10:35, 22 May 2015 (Magnus Robb) 6) IJmuiden, Noord-Holland, Netherlands, 07:51, 29 August 2007 (Magnus Robb)

At night, plik is by far the commonest Ortolan Bunting call we have recorded. Plik was present in 83 out of 141 recordings of nocturnally migrating Ortolans. Listen to an example of a nocturnal sequence. Below it is a sonagram and corresponding sound file showing six variations of this call type recorded at night.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, Cabriz, Sintra, Portugal, 01:19, 8 September 2012 (Magnus Robb). Sequence of plik calls from a passing nocturnal migrant.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana. Six variations of plik calls recorded by night. 1) Cabriz, Sintra, Portugal, 01:19, 8 September 2012 (Magnus Robb) 2) Portland Bill, Dorset, England, 23:27, 25 August 2016 (Nick Hopper) 3) Cabriz, Sintra, Portugal, 03:02, 26 September 2011 (Magnus Robb) 4) Cabriz, Sintra, Portugal, 23:21, 3 September 2012 (Magnus Robb) 5) Cabriz, Sintra, Portugal, 04:35, 6 September 2012 (Magnus Robb) 6) Sagres, Vila do Bispo, Portugal, 23:12, 3 October 2009 (Magnus Robb).

European Goldfinch Carduelis carduelis has a call similar to Ortolan Bunting’s plik, although it normally uses this call in combination with others. Goldfinches usually move around in tight flocks, and we have never recorded one migrating at night, despite it being such a common species.

European Goldfinch Carduelis carduelis, IJmuiden, Noord-Holland, Netherlands, 3 October 2005 (Magnus Robb). Plik-like calls of a single individual migrating. Note the variation in pitch and rhythm, giving a bouncing effect. On odd occasions when a single goldfinch repeats only its most plik-like calls, these are likely to be given in twos as well as singly, and with much shorter gaps than an Ortolan Bunting. Background: Dunnock Prunella modularis.

The following table compares measurements of plik calls recorded by day and by night. We limited the diurnal sample to birds identified both visually and aurally. For nocturnal plik calls, we chose the 18 clearest recordings from each country (PT for Portugal and UK for Dorset). Where there was more than one plik call in a recording we calculated the mean of up to three of the clearest ones. For each measurement we give the mean, standard deviation and range.

| Diurnal all | PT nocturnal | UK nocturnal | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 17 | 18 | 18 |

| Start frequency | 4354 ± 566 (2839-5210) | 4470 ± 348 (3899-5105) | 4499 ± 423 (3573-5108) |

| Frequency angle A | 3362 ± 519 (2512-4075) | 3562 ± 338 (2904-3986) | 3728 ± 390 (3070-4298) |

| Frequency angle B | 4328 ± 430 (3489-4857) | 4405 ± 298 (3924-4804) | 4443 ± 297 (4075-4968) |

| Freq B/Freq A | 1.299 ± 0.09 (1.151-1.435) | 1.242 ± 0.09 (1.131-1.426) | 1.211 ± 0.07 (1.069-1.336) |

| End frequency | 3741 ± 518 (3070-4605) | 3830 ± 361 (2919-4393) | 3935 ± 297 (3433-4522) |

| Total duration | 35 ± 3.79 (29-43) | 38 ± 6.13 (29-48) | 38 ± 4.65 (28-45) |

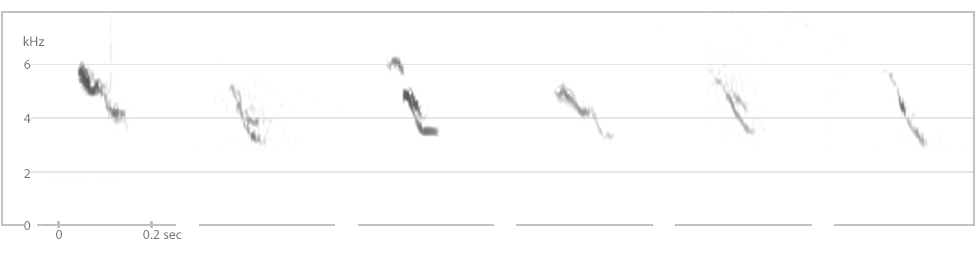

Pluk is the second commonest call type of migrant Ortolan Buntings during the day. Curiously, we have never recorded it at night. Pluk calls are low-pitched with a sharply ascending contour, the fundamental typically rising from 2 to 3.5 kHz in just 16 ms. This is the only Ortolan call likely to be doubled or trebled rapidly, and it is usually the first call we hear after flushing an Ortolan (they also pluk during longer flights). Pluk is one of the least variable calls, although occasionally we have recorded calls intermediate between plik and pluk. Listen to a typical example of pluk calls given just after taking off. Below it is a sonagram and corresponding sound file showing six variations of pluk calls recorded by day.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, IJmuiden, Noord-Holland, Netherlands, 17 September 2003 (Magnus Robb). Pluk calls shortly after taking off, with three plik calls.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana. Six variations of pluk calls recorded by day. 1) IJmuiden, Noord-Holland, Netherlands, 17 September 2003 (Magnus Robb) 2) Sagres, Vila do Bispo, Portugal, 08:24, 17 September 2008 (Magnus Robb) 3) Cabo Espichel, Setúbal, Portugal, 09:24, 11 October 2010 (Magnus Robb) 4) Chokpak, South Kazakhstan, Kazakhstan, 2 May 2000 (Magnus Robb) 5) Soguksu, Kızılcahamam, Turkey, 8 May 2001 (Magnus Robb) 6) Dadia, Evros, Greece, 2 May 2002 (Magnus Robb)

Of interest, the corresponding calls given by Ortolan Bunting’s closer relatives – species that give similar medleys of calls – are subtly different. These species are much rarer than Ortolan in a western European perspective. Here are low-pitched take-off calls of several from this group, plus the equivalent call of Yellowhammer E citrinella.

Cretszchmar’s Bunting Emberiza caesia, Wadi Dana, Jordan, 30 April 2004 (Magnus Robb). Various calls of a male, starting with the equivalent of Ortolan Bunting’s pluk.

Grey-headed Bunting Emberiza buchanani, ‘Van Hills’, Van, Turkey, 2 June 2002 (Magnus Robb). Calls when taking off, equivalent to Ortolan Bunting’s pluk.

Cinereous Bunting Emberiza cineracea semenowi, Nemrut Dag, Adiyaman, Turkey, 29 May 2002 (Magnus Robb). Low-pitched calls in flight, equivalent to Ortolan Bunting’s pluk.

Black-headed Bunting Emberiza melanocephala, Akseki, Antalya, Turkey, 11 May 2001 (Magnus Robb). Low-pitched calls in flight, equivalent to Ortolan Bunting’s pluk.

Red-headed Bunting Emberiza bruniceps, Chokpak, South Kazakhstan, Kazakhstan, 2 May 2000 (Magnus Robb). Low-pitched calls in flight, equivalent to Ortolan Bunting’s pluk.

Yellowhammer Emberiza citrinella, IJmuiden, Noord-Holland, Netherlands, 6 November 2003 (Magnus Robb). Calls when flushed.

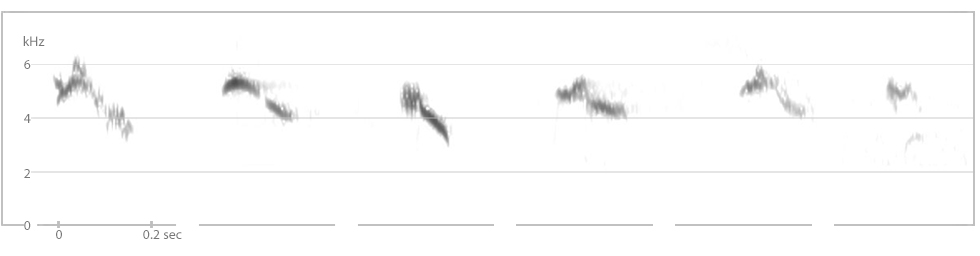

Tew is a common call-type used by migrant Ortolan Buntings both night and day. It is highly variable, and future studies may show that it can be divided into further types. What all tew calls have in common, however, is that they descend rapidly in pitch over a wide frequency range, more steeply at the start than at the end. A good feature to look for in sonagrams, when present, is one or more obvious kinks somewhere along the line where the slope changes. These help to distinguish Ortolan’s tew from similar calls of several other species. To the human ear tew always sounds monosyllabic. Similar calls that are audibly disyllabic are best classified as tslew. Listen to an example of a tew call recorded from a passing spring migrant, seen and heard by many observers. Below it is a sonagram and corresponding sound file showing six variations of tew calls recorded by day.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, Breskens, Zeeland, Netherlands, 08:02, 13 May 2007 (Magnus Robb). Tew and tsrp calls of one passing a ‘migration station’ by day.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana. Six variations of tew calls recorded during the day. 1) Breskens, Zeeland, Netherlands, 08:02, 13 May 2007 (Magnus Robb) 2) Chokpak, South Kazakhstan, Kazakhstan, 2 May 2000 (Magnus Robb) 3) Vedi, Ararat, Armenia, 15:37, 14 May 2011 (Magnus Robb) 4) & 5) Soguksu, Kızılcahamam, Turkey, 8 May 2001 (Magnus Robb) 6) Cabriz, Sintra, Portugal, 06:44, 1 October 2011 (Magnus Robb)

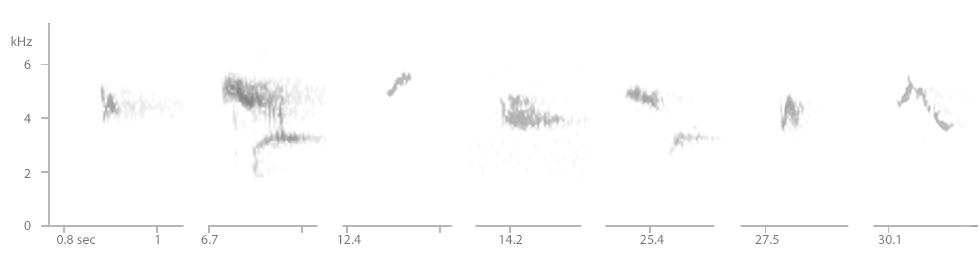

At night there were tew calls in 45/141 recordings. When they occur they are often repeated in sequences. This example from Poole Old Town has four tew calls. Below it is a sonagram and corresponding sound file showing six variations of tew calls recorded by night.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, Poole Old Town, Dorset, England, 03:08, 25 August 2016 (Paul Morton). Three tew calls of a passing nocturnal migrant.

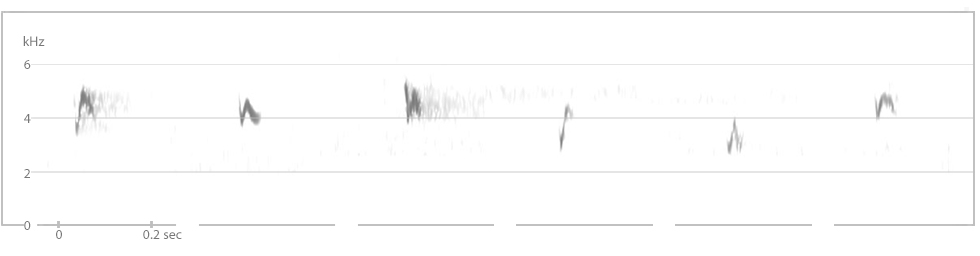

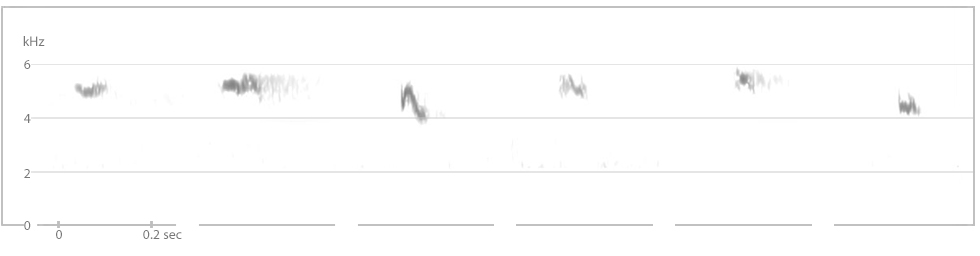

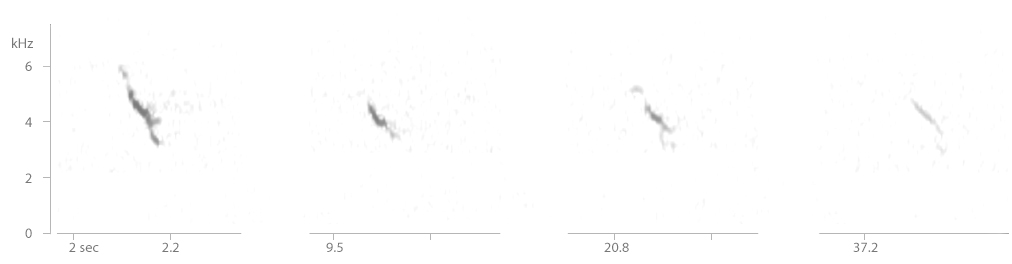

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana. Six variations of tew calls recorded during the night. 1) Poole Old Town, Dorset, England, 03:08, 25 August 2016 (Paul Morton) 2) Cabriz, Sintra, Portugal, 03:02, 26 September 2011 (Magnus Robb) 3) Poole Old Town, Dorset, England, 02:00, 24 August 2016 (Paul Morton) 4) Portland Bill, Dorset, England, 23:29, 25 August 2016 (Nick Hopper) 5) Cabo Espichel, Setúbal, Portugal, 01:06, 3 October 2015 (Magnus Robb) 6) Sagres, Vila do Bispo, Portugal, 22:42, 14 September 2011 (Magnus Robb)

The most likely confusion species for this call-type include ‘yellow wagtails’ (eg, Blue-headed Wagtail Motacilla flava), Lapland Longspur Calcarius lapponicus and Common Reed Bunting. We have recorded all of these as nocturnal migrants.

Blue-headed Wagtail Motacilla flava, Vila Real de Santo António, Algarve, Portugal, 08:31, 5 September 2009 (Magnus Robb). A small flock migrating. Some of the lower-pitched flight calls towards the end of the recording sound fairly similar to tew calls of Ortolan Bunting. Most flight calls of yellow wagtails are clearly higher-pitched, however, and descend most steeply towards the end of the call, whereas Ortolan shows the steepest descent at the start. Also, any ‘steps’ or ‘kinks’ tend to be in the upper half in yellow wagtails, but in the middle or lower half in Ortolan.

Lapland Longspur Calcarius lapponicus, IJmuiden, Noord-Holland, Netherlands, 28 September 2002 (Magnus Robb). Tew calls of an autumn migrant. These were recorded by day, but by night there can be a very real danger of misidentification. Although Lapland’s rattle or Ortolan Bunting’s plik or other call types immediately solve the identification, when we only hear tew, identification can be really challenging. Listen for a slightly higher pitch in Ortolan, and in sonagrams, look for the ‘kink’ that is often present in Ortolan, but lacking in Lapland.

Common Reed Bunting Emberiza schoeniclus, Nore og Uvdal, Trolltjörnstölan, Buskerud, Norway, 06:44, 5 July 2001 (Arnoud B van den Berg). Psieuw calls of a male. These are actually quite different from Ortolan, being both higher-pitched and having a much longer duration. Arguably, they are more likely to cause confusion with the disyllabic tslew call.

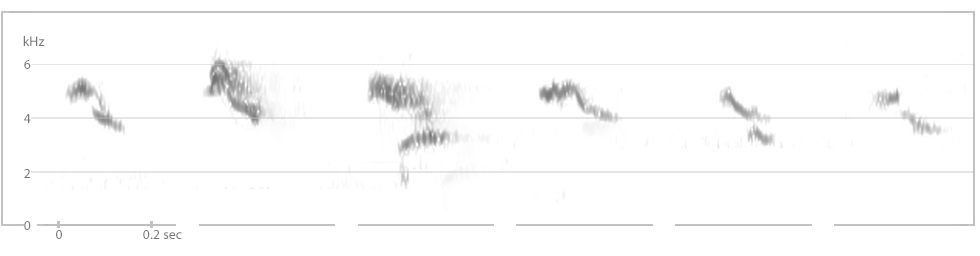

Tslew is another call type with a descending overall shape, commonly used both day and night. It differs from tew mainly in that it sounds clearly disyllabic. The first syllable is around 5 kHz, and sonagrams show that it usually has a slightly ascending shape. The second syllable lies between 3-4.5 kHz and is much more variable. It can descend from the first syllable like a tew call, or it can be completely separated from it and arch-shaped. Very often it actually overlaps in time with the first syllable, indicating that each was made with a different syrinx (birds have two vocal organs, one for each lung). In the following recording of a bird migrating on an autumn morning there are several tslew calls among a rich medley of other call types. Below it is a sonagram and corresponding sound file showing six variations of tslew calls recorded by day.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, Sagres, Vila do Bispo, Portugal, 08:26, 17 September 2008 (Magnus Robb). A rich medley of calls, including tslew from a migrant passing during the day.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana. Six variations of tslew calls recorded during the day. 1) Sagres, Vila do Bispo, Portugal, 08:26, 17 September 2008 (Magnus Robb) 2) Chokpak, South Kazakhstan, Kazakhstan, 2 May 2000 (Magnus Robb) 3) IJmuiden, Noord-Holland, Netherlands, 17 September 2003 (Magnus Robb) 4) Cabo Espichel, Setúbal, Portugal, 09:33, 3 September 2010 (Magnus Robb) 5) Sagres, Vila do Bispo, Portugal, 08:24, 17 September 2008 (Magnus Robb) 6) Berlenga, Leiria, Portugal, 11:19, 28 September 2011 (Magnus Robb)

At night there were tslew calls in 27 of our 141 recordings. When we record them they are often given in sequences. For example, there were six consecutive tslew calls in the following recording from Portland Bill; another from Poole Old Town also had six. Below this is a sonagram and corresponding sound file showing six variations of tslew calls recorded by night.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, Portland Bill, Dorset, England, 22:55, 25 August 2016 (Nick Hopper). Several tslew calls of a nocturnal migrant on a night of intense Tree Pipit Anthus trivialis migration.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana. Six variations of tslew calls recorded during the night. 1) Portland Bill, Dorset, England, 22:55, 25 August 2016 (Nick Hopper) 2) Cabriz, Sintra, Portugal, 02:02, 17 September 2012 (Magnus Robb) 3) Cabriz, Sintra, Portugal, 03:02, 26 September 2011 (Magnus Robb) 4) Poole Old Town, Dorset, England, 02:00, 24 August 2016 (Paul Morton) 5) Poole Old Town, Dorset, England, 02:46, 7 September 2016 (Paul Morton) 6) Cabriz, Sintra, Portugal, 05:49, 18 September 2015 (Magnus Robb)

Very few other species have calls similar to the tslew of an Ortolan Bunting. One that can sound a little similar at times is Eurasian Siskin Spinus spinus. We have only heard it once as a nocturnal migrant and that was less than 100% certain.

Eurasian Siskin Spinus spinus, IJmuiden, Noord-Holland, Netherlands, 09:01, 18 November 2007 (Magnus Robb). Social calls of a solitary migrant passing on autumn migration. Siskin will usually mix other calls in its flight sequences, making misidentification as an Ortolan Bunting highly unlikely.

Tsrp is the last of the calls commonly heard both by day and night. This is perhaps the most difficult Ortolan Bunting call to identify. Tsrp calls are so varied in shape that future studies may show this ‘type’ to be several. What all have in common, however, is that they are relatively high-pitched, monosyllabic and delivered on what sounds to the human ear like a single pitch: their inflections, which we can see on sonagrams, are not obvious to the ear. The whole call fits within a fairly narrow frequency range, typically centred around 5 kHz. Most have a slight huskiness, reminiscent of a Dunnock, and this is what sets them apart from plik calls. Listen to an example of diurnal tsrp calls in flight. Below it is a sonagram and corresponding sound file showing six variations of tslew calls recorded by day.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, Sagres, Vila do Bispo, Portugal, 08:21, 17 September 2008 (Magnus Robb). A medley of calls including many tsrp from a migrant in flight during the day.

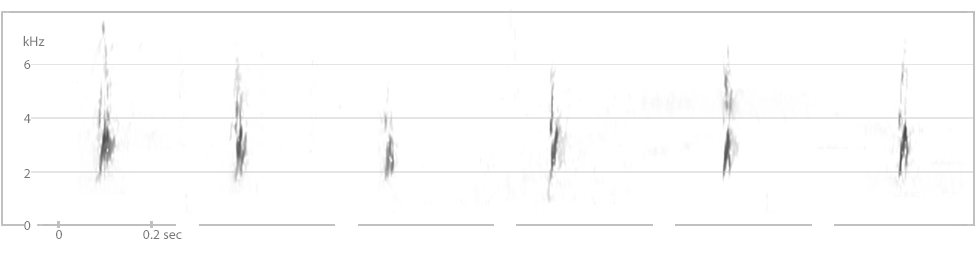

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana. Six variations of tsrp calls recorded during the day. 1) & 2) & 4) Sagres, Vila do Bispo, Portugal, 08:21 & 08:24 & 08:26, 17 September 2008 (Magnus Robb) 3) Breskens, Zeeland, Netherlands, 08:02, 13 May 2007 (Magnus Robb) 5) Sagres, Vila do Bispo, Portugal, 10:23, 10 September 2010 (Magnus Robb) 6) Vedi, Ararat, Armenia, 15:37, 14 May 2011 (Magnus Robb)

At night there were tsrp calls in 44 out of 141 recordings of passing migrants. Usually tsrp is given in the presence of other call types, and if plik is among them the mystery is soon solved. When plik is missing, it can be more difficult to identify. The following recording had MR stumped for a long time, and were it not for the tslew call also in this sequence, he might still be guessing. Below it is a sonagram and corresponding sound file showing six variations of tsrp calls recorded by night.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, Barão de São João, Lagos, Portugal, 21:14, 5 October 2009 (Magnus Robb). A series of tsrp calls with one tslew from a nocturnal migrant.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana. Six variations of tsrp calls recorded during the night. 1) Sagres, Vila do Bispo, Portugal, 21:14, 5 October 2009 (Magnus Robb) 2) Cabriz, Sintra, Portugal, 01:38, 13 September 2013 (Magnus Robb) 3) Poole Old Town, Dorset, England, 03:34, 30 August 2016 (Paul Morton) 4) Portland Bill, Dorset, England, 22:44, 5 September 2016 (Nick Hopper) 5) Cabriz, Sintra, Portugal, 05:38, 18 September 2015 (Magnus Robb) 6) Portland Bill, Dorset, England, 21:55, 25 August 2016 (Nick Hopper)

Possible confusion species for this call-type include Tree Pipit A trivialis, Dunnock and Yellowhammer. All are regular nocturnal migrants.

Tree Pipit Anthus trivialis, Shizzafon Kibbutz fields, Arava Valley, Israel, 08:00, 2 December 2001 (Killian Mullarney). Tip calls of a wintering individual. These are similar in pitch and duration to the tsrp of Ortolan Bunting, but more simple and pure-sounding.

Dunnock Prunella modularis, De Cocksdorp, Texel, Netherlands, 06:25, 6 September 2016 (Magnus Robb). Calls of a migrant at dawn, at first perched then flying off. Individual calls longer than tsrp of Ortolan Bunting, and often doubled in a way that excludes Ortolan.

Yellowhammer Emberiza citrinella, IJmuiden, Noord-Holland, Netherlands, 31 October 2002 (Magnus Robb). Dzheu calls of a passing migrant. Much coarser (more heavily modulated) than most Ortolan Bunting calls, although one visually confimed Ortolan did give a single call that was almost identical.

Three call-types more rarely heard from migrants

Puw is only occasionally used by Ortolan Buntings during migration, both by day and by night. However, a very similar call is common during the breeding season in situations where the nest or brood is under threat. This is a very low-pitched whistle reminiscent of a bullfinch Pyrrhula. In our recordings of migrants, the call usually descends from around 3 to 2.5 kHz and has a mean total duration of 64 mS (n=7 individuals). Listen to an example of puw calls used by a migrant during the day. Below it is a sonagram and corresponding sound file showing three variations of puw calls recorded by day.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, Sagres, Vila do Bispo, Portugal, 08:21, 17 September 2008 (Magnus Robb). A medley of calls, starting with puw, from a migrant in flight during the day.

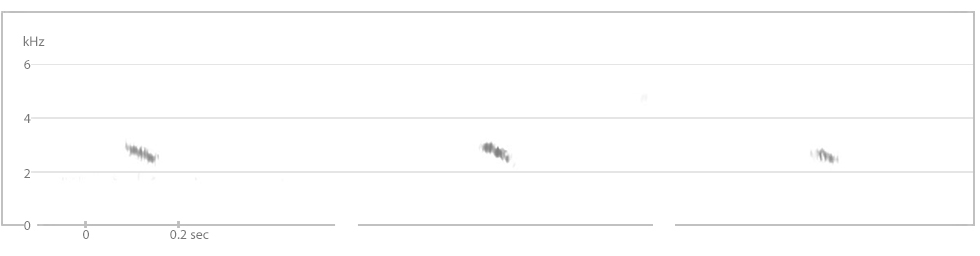

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana. Three variations of puw calls recorded during the day. 1) Sagres, Vila do Bispo, Portugal, 08:21, 17 September 2008 (Magnus Robb) 2) Madzharovo, eastern Rhodopi mountains, Bulgaria 09:58, 3 June 2009 (Arnoud B van den Berg) 3) Planalto de Mourela, Montalegre, Portugal, 10:35, 22 May 2015 (Magnus Robb)

At night there were puw calls in only 4 out of our 141 recordings of passing Ortolan Buntings, and we have not yet recorded this call type in Dorset. Listen to an example of puw calls in a rich nocturnal medley of other call-types recorded in Portugal. Below it is a sonagram and corresponding sound file showing three variations of puw calls recorded by night.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, Cabriz, Sintra, Portugal, 05:49, 18 September 2015 (Magnus Robb). Medley of puw and tslew calls of a nocturnal migrant.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana. Three variations of puw calls recorded during the night. 1) Cabriz, Sintra, Portugal, 05:49, 18 September 2015 (Magnus Robb) 2) Cabriz, Sintra, Portugal, 04:13, 13 September 2013 (Magnus Robb) 3) Cabriz, Sintra, Portugal, 03:26, 3 September 2016 (Magnus Robb)

Puw calls in isolation could be mistaken for a Eurasian Bullfinch Pyrrhula pyrrhula, although we have yet to hear a bullfinch migrating at night.

Eurasian Bullfinch Pyrrhula pyrrhula, Durlston, Dorset, England, 10:47, 6 October 2008 (Magnus Robb). Calls of a male just before taking off. Bullfinch calls are much longer than puw calls of Ortolan Bunting, so when comparing recordings directly it is easy to tell them apart.

Tup is another call only rarely used by Ortolan Buntings during migration, both day and night. This is a low-pitched, rapidly descending whistle strongly reminiscent of the flight call of a Common Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs. In our recordings, it descends from around 3.5 to 2.7 kHz, within a mean total duration of 47 mS (n=8 individuals). Perhaps puw and tup are merely longer and shorter versions of the same call. A larger sample of both may confirm or deny this possibility. Listen to an example recorded during the day. Below it is a sonagram and corresponding sound file showing three variations of tup calls recorded by day.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, Sagres, Vila do Bispo, Portugal, 08:26, 17 September 2008 (Magnus Robb). A rich medley of calls including tup, from a migrant passing during the day.

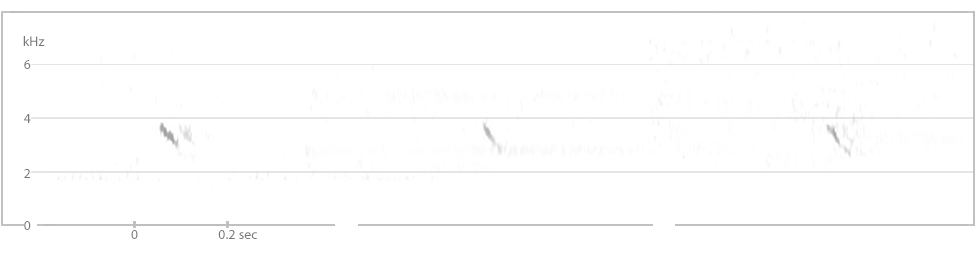

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana. Three variations of tup calls recorded during the day. 1) & 2) Sagres, Vila do Bispo, Portugal, 08:26 & 08:24, 17 September 2008 (Magnus Robb) 3) Madzharovo, eastern Rhodopi mountains, Bulgaria 09:58, 3 June 2009 (Arnoud B van den Berg)

At night there were tup calls in just 4 out of 141 recordings of migrating Ortolan Buntings. The bird in the following recording would probably have been mistaken for an early migrating Common Chaffinch had it not given some other Ortolan call types as part of its flight call medley.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, Cabriz, Sintra, Portugal, 00:26, 9 September 2015 (Magnus Robb). Tup and tslew calls of a nocturnal migrant.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana. Three variations of tup calls recorded during the night. 1) Cabriz, Sintra, Portugal, 00:26, 9 September 2015 (Magnus Robb) 2) Odeceixe, Aljezur, Portugal, 01:31, 31 August 2016 (Magnus Robb) 3) Cabriz, Sintra, Portugal, 02:19, 19 September 2016 (Magnus Robb)

Common Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs De Nolle, Zeeland, Netherlands, 11:30, 8 November 2011 (Magnus Robb). Flight calls of a bird passing on migration flight.

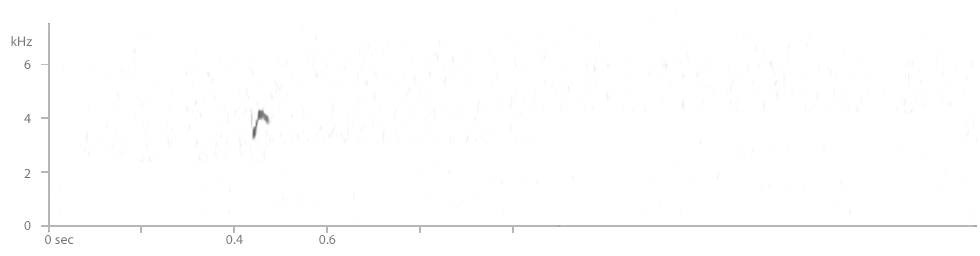

Vin is a strange little nasal call that we have recorded twice from migrants during the day, and twice at night. We have also recorded an identical call on the breeding grounds. This is a short, low-pitched, uninflected call with strong harmonics that give it a nasal timbre. Listen to an example from the breeding season, followed by one of a diurnal migrant.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, Planalto de Mourela, Montalegre, Portugal, 10:35, 22 May 2015 (Magnus Robb). Vin call and another rapidly rising call given by an Ortolan that approached the recordist. It may have had a nest close by.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, Sagres, Vila do Bispo, Portugal, 08:21, 17 September 2008 (Magnus Robb). A medley of calls, starting with vin, from a migrant in flight during the day.

Both times when we recorded vin at night, the caller was distant. In this example, the clearest call also coincides with a distant dog’s bark. Compare the calls in the sonagrams below, where the nocturnal example is the third in the row, following diurnal examples from each of the two recordings above.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, Cabriz, Sintra, Portugal, 00:26, 9 September 2015 (Magnus Robb). A medley of calls from a nocturnal migrant, starting with a vin call.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana. Two diurnal and one possible nocturnal vin call. 1) Planalto de Mourela, Montalegre, Portugal, 10:35, 22 May 2015. (Magnus Robb) 2) Sagres, Vila do Bispo, Portugal, 08:21, 17 September 2008 (Magnus Robb) 3) Cabriz, Sintra, Portugal, 00:26, 9 September 2015 (Magnus Robb)

If anything, vin resembles a very short version of the ‘trumpet’ call given by some Northern Bullfinches P p pyrrhula, but other call types given as part of the Ortolan Bunting’s medley should soon put any such ideas to rest.

Northern Bullfinch Pyrrhula pyrrhula pyrrhula, De Nolle, Zeeland, Netherlands, 10:50, 8 November 2005 (Magnus Robb). ‘Trumpet’ calls of a female migrating with Brambling Fringilla montifringilla. Vin calls of Ortolan are much shorter.

Cabriz, Sintra, and various sites in southern Portugal – Magnus Robb

Magnus Robb took an interest in night migration recording after moving to Portugal at the end of 2008. While enquiring about good sites for diurnal migration, he heard that nocturnal migration could be impressive at Sagres, Vila do Bispo, near Cape St Vincent, the southwestern corner of the European mainland. An old fortress south of the town sits on a peninsula forming the last point of land for birds heading towards Morocco and beyond. At night, it is usually floodlit, which can disorientate migrants and make it more likely that they will call. MR started recording night migration there in early October 2009 and was surprised to record six Ortolan Buntings in the first five hours. Here is the second of those six.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, Sagres, Vila do Bispo, Portugal, 23:12, 3 October 2009 (Magnus Robb). Plik and tew calls of a passing nocturnal migrant. Recorded with Sennheiser MKH-20 microphones in an altered Crown SASS binaural casing.

During the rest of that autumn and the next, MR recorded other nocturnal Ortolan Buntings at Sagres and two other sites. Clearly, the audible migration of this species at night was a normal phenomenon in Portugal. At the end of 2010, he moved house from Lisbon to Cabriz, a village near Sintra, about 25 km northwest of the capital. The following autumn he tried his luck at the house and during one of the first recording sessions an Upland Sandpiper Bartramia longicauda flew over. Despite the neighbours having too many barking dogs, it certainly seemed worthwhile to persevere.

Cabriz is now MR’s main site for nocturnal migration, since no travel is required in order to record there. Due to cars, neighbours, dogs and other noise, sessions usually only start later in the evening when things have become quieter. However, occasional all-night sessions have shown that much fewer birds can be detected during the first half of the night. The same effect does not seem to occur at Sagres, where migration is typically worth recording throughout the night. MR rarely records on spring nights, since the results of a few trial runs have been very disappointing. This is presumably for geographical reasons. Many migrants that passed in the autumn are known to take a more easterly route through Spain when returning to their breeding grounds, and very few long distant land migrants have good reason to pass over the Portuguese west coast in spring.

At Cabriz, Ortolan migration is essentially a September phenomenon, with 79 nocturnal recordings from that month and only 6 from October. So far there are none from August, when MR is often away from home. Elsewhere in Portugal, he has recorded Ortolan twice in August, both times on the last day of the month. In September, Ortolan is among the species recorded most often, after Pied Flycatcher Ficedula hypoleuca and Tree Pipit Anthus trivialis, and the record for one session currently stands at 20 individuals, recorded between 00:20 and 06:41 on 20 September 2012. Occasionally, more than one Ortolan passes at the same time. Here is an example from 26 September 2011 with one near and one distant individual (the more distant one calls for the first time at 0:12).

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, Cabriz, Sintra, Portugal, 03:02, 26 September 2011 (Magnus Robb). Plik, tslew, tsrp and tew calls of two nocturnal migrants, one near and one far (the latter audible from 0:12).

Remarkably, MR has never seen or heard an Ortolan Bunting in the immediate surroundings of Cabriz during the day, although he has seen them migrating along the Atlantic coast just 7 km to the west.

Recording equipment used: Telinga Pro V parabola with stereo DATmic, recording onto Sound Devices 722 solid state recorder.

Old Town Poole – Paul Morton

Spurred on in part by what MR and Nick Hopper (see below) were recording, as well as by the sheer mystery of it all, Paul Morton started recording night migration in February 2015. His first listening station was his back garden in the rural village of Lytchett Matravers, four miles northwest of Poole Harbour, Dorset. During the course of the spring, wader passage was prominent and he also recorded night migrants such as Water Rail Rallus aquaticus, European Nightjar Caprimulgus europaeus and Ring Ouzel Turdus torquatus. Migration petered out in late spring, but waders started moving again in July. By August, passerines featured again, and on 17 August PM noted an unknown call of a bird that had passed at 00:12. He cut it out and filed it away without any real expectation of being able to identify it. A week later at the British Birdwatching Fair, he played the recording to MR who jerked back his head and said, “Where did you say you recorded this?” to which PM replied, “Over my house last week.” MR raised an eyebrow and said, “This sounds like an Ortolan Bunting to me.”

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, Lytchett Matravers, Dorset, England, 00:12, 17 August 2015 (Paul Morton). Single plik call of a nocturnal migrant.

The recording contained a single but entirely typical plik call. As we showed in part 1, plik is the commonest and most easily recognisable of the calls that Ortolan Bunting uses during nocturnal migration. Enthused but nevertheless convinced this would be a one-off, PM continued recording night migration over the following weeks. To his surprise, however, at 04:38 on 10 September he recorded another giving one plik and one tew call.

In 2016, PM decided to move his nocturnal listening station away to a site within Poole Harbour. This was partly to begin a study of night migration within the harbour area for the charity he runs called Birds of Poole Harbour, but also to allow him to place the listening station on a more prominent migration route. He hoped this would result in a wider variety of species and greater numbers of individuals. The new listening station is at the top of a four-story building in the centre of Old Town Poole, an urban environment with virtually no vegetation in the surrounding area to support either resident or migratory birds. Due to the lack of habitat locally, any birds recorded overhead during the night at the appropriate season are very likely to be migrants. Noise from traffic and the local ferry port can sometimes be infuriating, but the expectation of greater variety and numbers proved to be correct. Spring recording was productive with good wader passage and an unexpectedly large Redwing Turdus iliacus movement in March. Autumn recording commenced on 1 August and remained uneventful until 22 August when PM came across a single tew call of an Ortolan Bunting. Much better was to follow the next night when, as the clock struck two, he recorded a long medley of tew and tslew calls of an Ortolan approaching and flying low over the microphones.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, Old Town Poole, Dorset, England, 02:00, 24 August 2016 (Paul Morton). Tew and tslew calls of a nocturnal migrant passing at close range.

The following night, three Ortolan Buntings passed. This late August wave coincided with the first visual records for the autumn at coastal sites such as Portland Bill and Hengistbury Head, as well as other sites on the south coast. Between 25 August and 12 September, PM recorded a further eight Ortolans, bringing his 2016 total to 13 recordings in just 22 days. After this date there was no further sign of them in his night recordings, and visual records by day also tailed off. It will come as no great surprise that PM has never seen or heard an Ortolan near the Old Town Poole listening station during the day.

Recording equipment used: Telinga Pro 8 parabola with stereo DATmic, recording onto a Sound Devices 722 solid state recorder.

Portland Bill and Stoborough – Nick Hopper

Nick Hopper started recording nocturnal migration from the roof of his house in Stoborough, in the far southwestern corner of Poole Harbour, during the autumn of 2012 after being inspired by an email from MR detailing the species he had recently recorded in Portugal. His first thoughts were ‘what a great way to add species to your garden list!’ After persuading The Sound Approach to loan him some equipment, he was ready to go. The parabolic dish went on the roof, and the recorder in the bedroom, connected via some very long cables. All he had to do now was lie in bed with his headphones on and listen. He soon added species such as Common Moorhen Gallinula chloropus, Eurasian Coot Fulica atra and Water Rail Rallus aquaticus to the garden list, and after only three attempts struck gold when a Lapland Longspur Calcarius lapponicus flew over the house. Unfortunately ‘listening live’ proved to be a little anti-social and sessions were rather intermittent until NH adopted the more orthodox approach of leaving the recorder running through the night then checking the sonagrams the next day. The site, adjacent to the Frome Valley, has produced 72 species so far between nautical dusk and nautical dawn (ie, with the sun 12 or more degrees below the horizon). Waders and water birds are a regular feature as might be expected, along with plenty of passerines and oddities such as Mandarin Duck Aix galericulata, Common Scoter Melanitta nigra, Little Grebe Tachybaptus ruficollis, Sandwich Tern Sterna sandvicensis and Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana. In autumn 2014, NH started recording night migration from Portland Bill, Dorset. The volume and variety of migrants passing at Portland proved to be much greater, and NH has subsequently invested more time in this listening station.

The first time NH recorded Ortolan Bunting at night was at Portland Bill on the night of 25-26 August 2016. It was a promising-looking night with heavy cloud cover and occasional pulses of drizzly rain. These conditions together with the date were perfect for a strong audible passage of Tree Pipits Anthus trivialis, and the night’s total came to an incredible 1372 calls (with double and triple calls counted as one). NH spent the first few hours of darkness in the field and to his amazement heard two different Ortolans heading north over the Bill. Later analysis of the night’s recording revealed yet more birds.

Not wanting to push his credibility too far, he selected four examples separated by gaps of 30 minutes or more, and a few days later he uploaded the three best ones to the Portland Bird Observatory website. However, the total number of times that Ortolans passed his microphones that night was 10. Here is one that passed at 22:55. The recording was included in part 1, but it is well worth listening to again. Were these all different individuals? We will come back to this question later. However, since PM recorded three over urban Old Town Poole the night before, there seems no reason to doubt that NH could record an even higher number of them at one of the country’s top sites for Ortolan.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, Portland Bill, Dorset, England, 22:55, 25 August 2016 (Nick Hopper). Several tslew calls of a nocturnal migrant on a night of intense Tree Pipit Anthus trivialis migration.

On the night of 30-31 August NH recorded two more Ortolans, this time at Stoborough. Here is one that passed at 01:03, giving a single plik followed by long series of tew calls.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, Stoborough, Dorset, England, 01:03, 31 August 2016 (Nick Hopper). A series of tew calls from a passing nocturnal migrant.

On the night of 2-3 September, another session at Stoborough produced no Ortolans and indeed very little of anything at all. Two nights later at Portland there were none, but the evening of 5 September produced another six Ortolan recordings. At 22:44, one flew over NH who was standing a couple of hundred metres away from his equipment at the time. Here is what was recorded a few moments later.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, Portland Bill, Dorset, England, 22:44, 5 September 2016 (Nick Hopper). Plik and two tslew calls of a nocturnal migrant.

Further sessions at Portland on 18-19 and 19-20 September, and at Stoborough on 23-24 September produced no further recordings. However, the odd Ortolan was still being seen during the daytime hours on Portland until 19 September. Portland has always been one of the best places in England to see Ortolan Bunting, and 2016 was a good year.

Equipment used: Telinga Pro 8 parabola with stereo DATmic, recording onto Tascam HD-P2 solid state recorder.

How we analyse the recordings

Anyone first hearing about our habit of making all-night sound recordings is bound to ask, when do we ever find the time to listen to them? The answer is that we don’t. We import the recordings into a software program that produces a sonagram: a visual image of the recording. We scroll through these quickly in search of tell tale shapes of flight calls, which we then listen to. We log species and numbers, archiving the more interesting recordings for future reference.

The software we use is Raven Pro, currently in version 1.5 (birds.cornell.edu/brp/raven/). The time it takes to go through the recording depends on how much migration has taken place through the night. A quiet night might take less than an hour, but a night with many challenging calls to be identified, counted and filed away can take many hours. It is often only some days later that we appreciate fully what went on during a given night, and this is why news sometimes gets out slowly.

Results

Ortolan Bunting nocturnal flight call recordings in 2016

Table 1. Medleys of Ortolan Bunting nocturnal flight calls, recorded by the authors during the autumn migration period in 2016. The abbreviations given under Loc (location) are as follows: OTP – Old Town Poole, Dorset, England; SB – Stoborough, Dorset, England; PB – Portland Bill, Dorset, England; OD – Odeceixe, Aljezur, Portugal; CZ – Cabriz, Sintra, Portugal.

| Loc | Date | Time | Medley of calls recorded |

|---|---|---|---|

| England | |||

| OTP | 22-aug | 22:47 | tsrp |

| OTP | 24-aug | 02:00 | tslew, tew, tew, tslew, tslew, tew, tslew, tslew, tslew |

| OTP | 24-aug | 22:40 | plik |

| OTP | 25-aug | 01:31 | plik, tew, tew, tsrp, tew, tew, tsrp, tslew |

| OTP | 25-aug | 03:08 | tew, tew, tew, tew |

| OTP | 25-aug | 22:27 | tew |

| OTP | 27-aug | 02:03 | plik |

| OTP | 29-aug | 21:37 | plik, tslew |

| OTP | 30-aug | 03:34 | tsrp, plik |

| OTP | 01-sep | 02:33 | plik, tew |

| OTP | 05-sep | 20:53 | tsrp, tslew, tslew, tslew |

| OTP | 07-sep | 02:46 | tsrp, tslew |

| OTP | 12-sep | 01:12 | plik |

| ST | 31-aug | 01:03 | tew, tew, tew, tew, tew, tew |

| ST | 31-aug | 02:11 | plik, tew |

| PB | 25-aug | 21:33 | tew, tew |

| PB | 25-aug | 21:55 | tsrp |

| PB | 25-aug | 22:35 | tsrp, tsrp |

| PB | 25-aug | 22:55 | tslew, tslew, tslew, tslew, tslew, tew, tslew, tew |

| PB | 25-aug | 23:25 | tew, tew, tew |

| PB | 25-aug | 23:27 | plik, tew, plik |

| PB | 25-aug | 23:29 | tew, tew, tew, tew |

| PB | 26-aug | 00:12 | plik |

| PB | 26-aug | 00:35 | plik, plik, plik, plik (possibly two individuals) |

| PB | 26-aug | 02:06 | tslew, tslew |

| PB | 05-sep | 21:17 | plik, tew |

| PB | 05-sep | 21:39 | plik |

| PB | 05-sep | 21:54 | tslew, tsrp, tsrp, tsrp |

| PB | 05-sep | 22:35 | tsrp, plik |

| PB | 05-sep | 22:40 | plik |

| PB | 05-sep | 22:44 | plik, tsrp, tsrp |

| Portugal | |||

| OD | 31-aug | 01:31 | tew, tup |

| CZ | 02-sep | 01:21 | plik |

| CZ | 03-sep | 03:26 | plik, puw, tslew, puw, tslew |

| CZ | 03-sep | 05:21 | plik, tsrp? |

| CZ | 03-sep | 05:32 | plik, plik |

| CZ | 17-sep | 00:06 | tew, tsrp, tew |

| CZ | 17-sep | 00:13 | plik, tslew? |

| CZ | 17-sep | 01:29 | tsrp |

| CZ | 17-sep | 01:46 | plik, plik, plik |

| CZ | 17-sep | 01:49 | tew, tew |

| CZ | 17-sep | 02:54 | plik, tsrp |

| CZ | 17-sep | 03:07 | plik, plik |

| CZ | 17-sep | 03:57 | plik, tew |

| CZ | 17-sep | 05:12 | plik |

| CZ | 18-sep | 23:18 | unclear, plik |

| CZ | 18-sep | 23:54 | plik |

| CZ | 19-sep | 00:44 | tew, tsrp, plik, tslew, plik, vin (two individuals) |

| CZ | 19-sep | 00:51 | tslew |

| CZ | 19-sep | 01:48 | tslew, tsrp? |

| CZ | 19-sep | 02:19 | plik, tup, tup, tup |

| CZ | 19-sep | 02:38 | plik |

| CZ | 19-sep | 22:50 | tew, tew |

| CZ | 06-okt | 06:24 | plik |

Do all the recordings in Dorset represent different individuals?

In late August 2016, when the news first emerged that we had sound recorded multiple Ortolan Buntings flying at night over Dorset, sceptics wondered whether this was all down to one or two birds flying circuits, and being responsible for multiple detections. At Old Town Poole this seems extremely unlikely because of the habitat – an urban centre – and besides, all recordings were separated by at least 97 minutes. At Portland Bill, however, there were a couple of obvious clusters of records: three detections in under five minutes on 25 August (23:25-23:29) and three detections in under 10 minutes on 5 September (22:35-22:44).

Several interpretations are possible. Perhaps in both cases a group of three took off from a feeding area at dusk, gradually became separated in the dark, and each individual ended up passing the Bill at a slightly different time. Alternatively, a single bird could have flown a couple of circuits of Portland Bill before deciding how to procede further. On 25 August, there was heavy cloud cover with occasional drizzle and the fog horn was in operation, conditions that could cause some disorientation. On 5 September, the sky was overcast but it was not raining.

During such conditions it was also possible that birds could have been temporarily grounded for short periods of time during heavier bouts of rain. One way to shed some light on the problem is to consider the actual calls recorded. After viewing sonagrams of over 140 recordings of nocturnally migrating Ortolans, it seems clear to us that calls of a given type from the same individual are usually more similar than calls of the same type from two different individuals.

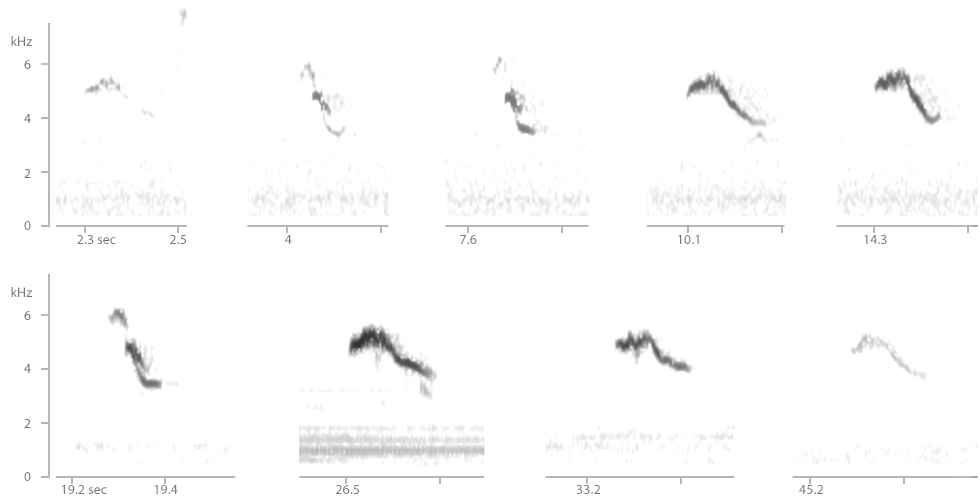

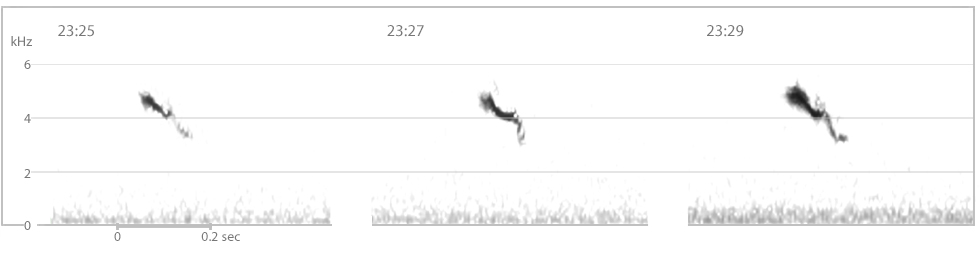

For this reason we compared each recording from Portland Bill with the two before and after on the same night. It was striking that the tew calls at 23:25, 23:27 and 23:29 on 25 August all had a very similar shape, even if the one at 23:27 was angled differently in its final, lowest part. It seems likely that the same individual was involved in all three.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, Portland Bill, Dorset, England, 23:25, 23:27 & 23:29, 25 August 2016 (Nick Hopper). Tew calls from three recordings made with gaps of two minutes between them. Probably the same individual was in all three.

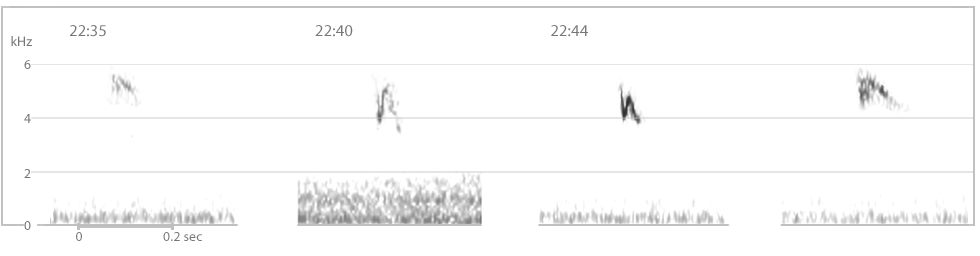

In the sequence of three detections in under 10 minutes on 5 September, the tsrp calls at 22:35 and 22:44 are very similar in pitch, timbre and shape, and the plik calls at 22:40 and 22:44 are similar in frequency range if not exactly in shape. Perhaps here also, the same individual was involved in all three.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, Portland Bill, Dorset, England, 22:35, 22:40 & 22:44, 5 September 2016 (Nick Hopper). Tsrp and plik calls from three recordings all made within 10 minutes and probably involving the same individual.

Based on the above we will err on the side of caution and propose 27 individuals from the 31 recordings of Ortolan Buntings detected nocturnally in Dorset in 2016.

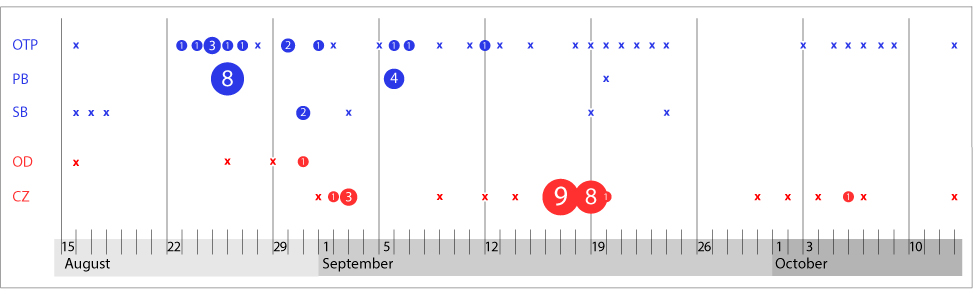

Phenology of nocturnal Ortolan Bunting migration at five listening stations. Numbers refer to estimated number of individuals, which may differ from the number of recordings. Nights when we recorded migration but detected no Ortolans are indicated with a cross mark. Dorset locations blue; Portuguese locations red.

Variable amounts of information in nocturnal recordings

In part 1, we showed how to identify eight different call types of Ortolan Bunting, seven of which we have also detected at night. As we showed, nocturnal and diurnal versions of these calls do not differ. Some, such as plik are highly distinctive, while others such as tsrp are more likely to invite confusion with other species.

Recordings of nocturnally migrating Ortolan Buntings can contain vastly different amounts of information. The main variables concern the number, variety and clarity of calls. It is undeniable that a recording with five different known Ortolan call-types, some of them repeated, and passing at close range can be more securely identified than one containing a single distant tsrp call.

With sound identification, just as with visual identification, the more features that point in the same direction, the better. In this respect Ortolan Bunting, with so many different call types, offers greater chances of secure identification than a species with few and rather undistinctive call types ever could. In 2016 the mean number of call types given by a passing nocturnal Ortolan was 1.56 (range: 1 – 5); 58% only gave a single call-type while within range of the microphones. Of the latter group, 16 used plik, 8 tew, 4 tsrp and 2 tslew.

What weather conditions are best for detecting Ortolans at night?

Stars are among the most important means by which birds navigate at night (Newton 2008), and on a clear night in autumn many birds will be migrating. When conditions are favourable for them many of these birds, particularly passerines, will be at a high altitude and therefore beyond the range of our listening equipment. We have found that nights with heavy cloud cover and even intermittent light rain often give the best results, presumably because birds are forced down to a more audible altitude.

During 2016, the best nights in Dorset were mild with dense cloud cover. Prior to 2016, NH chose to record only on nights with no or little cloud cover, since he was concerned that the expensive recording equipment might not be waterproof. During those times, although he recorded many species, passerine numbers were much lower than in 2016 and he detected no Ortolan Buntings.

The two best nights in Portugal in 2016 coincided with high pressure over the Iberian peninsula. MR associates good Ortolan nights with light tailwinds and cloudy conditions, although multiple individuals may also pass on clear nights. Northerly tailwinds are the norm in Portugal in late summer/early autumn. Indeed, it may be for this reason that so many Ortolans head so far west in autumn, to hitch a ride to subsaharan Africa on the prevailing northerly winds of the Iberian west coast.

Was 2016 an exceptional year in Dorset?

It is impossible to say whether, in terms of nocturnal migration, 2016 was an exceptional year for Ortolan Buntings in Dorset. We simply do not have comparable coverage from other years. In terms of visual sightings, however, it was a good year. The Portland Bird Observatory blog lists a minimum of 12 flighty individuals seen between 26 August and 19 September 2016. None were “pinned down and showing”, and only the very last one lingered long enough to be photographed. However, there was no obvious link between numbers seen during the day and numbers recorded during the night.

Ortolan Bunting Emberiza hortulana, Portland Bill, Dorset, England, 19 September 2016 (Martin Cade).

Why so many Ortolans at night?

Why is a species that is scarce or even rare during the day among the ones that we pick up most frequently at night, even in places where we have never seen or heard it during the day? It is not the only such species. Tree Pipit Anthus trivialis is another that manages to keep a very low profile during the day, even for observers very familiar with its calls. During the night, however, we sometimes detect heavy passage (eg, the 1372 calls at Portland Bill on 25-26 August 2016 referred to above). In North America, Catharus thrushes are notoriously difficult to detect as migrants during the day and yet, as nocturnal migrants they are available to anyone who makes the effort to listen for them, often passing locations where they have never been detected in any other way (Evans & O’Brien 2002). Is Ortolan simply a shy species like Tree Pipit and the Catharus thrushes, but highly vocal as a nocturnal migrant? Perhaps it really is that simple.

After learning to recognise calls of Ortolan Bunting, our experience has been that most autumn observations by day concern birds flying past or, much less often, flushed. Occasionally a bird flushed unexpectedly will perch on a nearby bush, allowing us perhaps brief views. However, opportunities for identifying them only by visual means are very limited. Even in Portugal where Ortolan is not particularly rare, you need enormous luck to chance upon a feeding site. If you do find one during the peak of migration, it may hold several 10s of individuals. MR knows of just two such sites in southern Portugal. Probably there are many more, in arable land not often frequented by birders.

There are many species we know to be much commoner night migrants than Ortolan Bunting, which we never or only very rarely detect during our listening sessions. An obvious group to mention here is the old world warblers, of which only Phylloscopus seem to give the occasional call in nocturnal flight (10 in eight years of recording: MR). Also, many but not all of the chats, such as Whinchat Saxicola rubetra and Common Redstart Phoenicurus phoenicurus, appear to migrate silently. Among buntings, Common Reed Bunting E schoeniclus is mysteriously rare in our nocturnal recordings, despite being a common migrant and calling frequently while migrating during the day. At night, Ortolans seem to feature disproportionately often in our recordings, compared to many other species. Why should this be?

One possibility is that Ortolan Bunting flies lower than other nocturnal migrants, increasing our chances of detecting it. Why might it do this? Migrants are thought to choose the height they migrate at based on the help they receive from wind strength and direction (Bruderer 1971, Richardson 1976). So there would have to be some major advantage to flying low, in order to compensate for the advantages of choosing a more aerodynamic stratum, usually higher in the sky.

Conclusion

We confess that we are still almost as amazed by the number of Ortolans we are detecting at night as we were when we first started detecting them. Who will join us in trying to shed more light on the phenomenon? Lets find out where else besides Dorset and southern Portugal they can be detected migrating at night, and where the numbers are highest. And having established that numbers migrating through England are higher than previously thought, lets try to work out where they are hiding during the day.

Meanwhile, what other surprises await discovery? Who will be the first to detect a Catharus thrush or an Olive-backed Pipit A hodgsoni migrating over a western European location at night? Or one of the eastern relatives of Ortolan Bunting: a Cretzschmar’s Bunting E caesia or even a Grey-necked Bunting E buchanani? Many exciting rewards are possible in this ‘new’ branch of birding, and they are open to anybody curious enough to give it a try.

By now we hope it is clear that the nocturnal flight calls we have identified as Ortolan Bunting are fully compatible with six or seven of the eight call-types we have recorded from migrants during the day. Nocturnal Ortolans can be identified with higher confidence when we hear more than one of these call-types, and this is in fact what nearly always happens. When we only hear plik, we can still identify the bird with a high degree of confidence. When we only hear one of the other three common nocturnal call-types, we have to be more cautious, considering the possibility of confusion with several other species that occur regularly as nocturnal migrants.

In eastern Europe, there are several other species of bunting that deliver their flight calls in a similar ‘medley’ style. These include Red-headed Bunting E bruniceps, Black-headed Bunting E melanocephala, Cinereous Bunting E cinerea, Cretzschmar’s Bunting E caesia and Grey-headed Bunting E buchanani. The Sound Approach has recordings of flight calls of all these species, and none appear to match any of Ortolan Bunting’s eight flight call types exactly. However, we do not know them nearly so well, as they are vagrants in our own countries. We hope that in future we will be able to gain more experience of these species in a migration context, to help exclude the highly unlikely possibility that we have been recording any of them at night in Dorset or Portugal.

References

Bruderer, B 1971. Radiobeobachtungen über den Frühlingszug im Schweizerischen Mittelland. Ornithologischer Beobachter 68: 89-158.

Evans, W R & O’Brien, M 2002. Flight calls of migratory birds. Eastern North American landbirds. CD-ROM. Old Bird Inc.

Newton, I 2008. The migration ecology of birds. London.

Richardson, W J 1976. Southeastward shorebird migration over Nova Scotia and New Brunswick in autumn: a radar study. Canadian Journal of Zoology 57: 107-124.