Shortly after midnight, a male Arabian Eagle-Owl Bubo milesi lands on a sturdy branch overlooking a monsoon pool in southern Oman. Every few seconds he croons two notes, the first longer than the second (CD3-12). His voice is languid, not fierce or imposing. Arabian Eagle-Owl is one of the smallest members of the genus Bubo and has a diet to match. Soon some Dhofar Toads Bufo dhufarensis strike up a chorus. The owl is not here by chance. Bubo is here to hunt Bufo.

CD3-12: Arabian Eagle-Owl Bubo milesi Wadi Darbat, Dhofar, Oman, 00:28, 18 July 2013. Hooting of a presumed male. Background: Singing Bush Lark Mirafra cantillans and Dhofar Toad Bufo dhufarensis. 130718.AB.002826.12

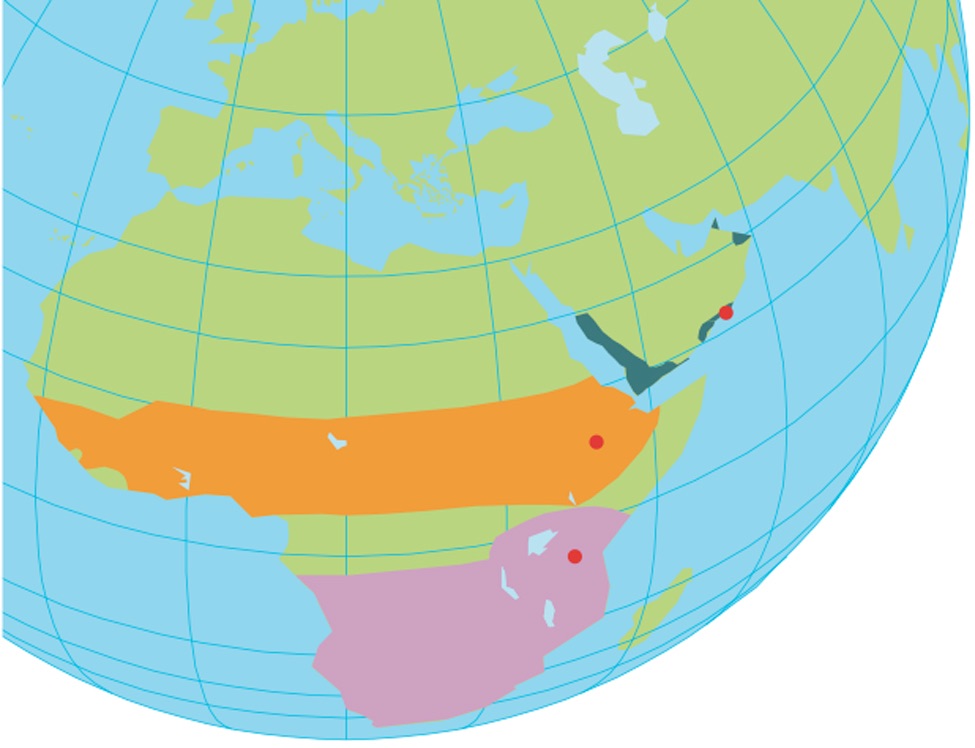

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first sound recording of Arabian Eagle-Owl ever to be published. Up to now, taxonomists have only had museum skins to work with. That is why they lumped Arabian with Spotted Eagle-Owl B africanus, a common species in Africa south of the tropical forest and, until recently, Greyish Eagle-Owl B cinerascens living to the north of Spotted. To date, there have been no genetic studies involving all three of these former subspecies. They do seem likely to be each other’s closest relatives, as they show broad similarities in plumage and size, in vocalisations, and share a similarly varied diet of insects and small vertebrates. However, there are important differences in the tone and patterning of their plumage, their eye colour and their sounds.

Approximate breeding distribution of Arabian Eagle-Owl Bubo milesi (green) , Spotted Eagle-Owl B africanus (pink) and Greyish Eagle-Owl B cinerascens (orange) Recording locations indicated by red dots.

The male Arabian Eagle-Owl in CD3-13 is a different individual that was also hunting toads during the July monsoon. His hooting is slower than most, with phrases 4.3 seconds long. Male Spotted Eagle-Owls also hoot with a high and slightly longer first note followed by a low second one (CD3-14). However, their two notes are much shorter than those of Arabian, and the whole phrase is delivered in less than half the time. Hooting of male Greyish Eagle-Owl resembles that of Spotted but is delivered more slowly (CD3-15). Despite this, the phrases are much shorter than in Arabian.

CD3-13: Arabian Eagle-Owl Bubo milesi Wadi Darbat, Dhofar, Oman, 20:51, 15 July 2013. Hooting of a presumed male. Background: Arabian Scops Owl Otus pamelae. 130715.AB.205100.12

CD3-14: Spotted Eagle-Owl Bubo africanus Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania, July 1986. Hooting duet of male and female, starting with the male. David Moyer & The Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

CD3-15: Greyish Eagle-Owl Bubo cinerascens Langano, Oromia, Ethiopia, 12:30, 17 February 2011. Hooting of a male. The gaps between hoots have been shortened by about 30%. Background: African Mourning Dove Streptopelia decipiens, Laughing Dove S senegalensis and Rüppell’s Starling Lamprotornis purpuroptera. Jelmer Poelstra.

Left: Arabian Eagle-Owl Bubo milesi, Wadi Darbat, Dhofar, Oman, 18 July 2013 (Arnoud B van den Berg). Centre: Spotted Eagle-Owl B africanus, female, Kalahari Gemsbok NP, South Africa/Botswana, 12 March 1996 (Arnoud B van den Berg). Compare CD3-14. Right: Greyish Eagle-Owl B cinerascens, Langano lake, Oromia, Ethiopia, 23 September 2004 (Dick Forsman). At same site as in CD3-15. Arabian Eagle-Owl has bright yellow eyes, surrounded by a black orbital ring (and black spot on eye-lid). The iris of Spotted Eagle-Owl is similar, although it can be more orange. Greyish Eagle-Owl is the odd one out, having dark brown iris with pinkish orbital ring. Owls with dark eyes usually lead the darkest lives (Galeotti & Rubolini 2007). We are not aware of any daytime observations of Arabian but its habitat is fairly open and therefore not very dark. In the Natural History Museum at Tring, England, Arnoud photographed skins of Arabian from Oman and Spotted from South Africa and came to the same conclusion as his old professor (Voous 1988): Arabian is paler, tawnier and slightly smaller than Spotted. The markings are much finer and more speckled or vermiculated, particularly on the head and mantle, where the Spotted has larger white spots. Greyish also has a finely marked head and neck, but differs from both Arabian and Spotted in being darker and having a colder tone to its plumage.

When Richard Bowdler Sharpe described Arabian Eagle-Owl in 1886, he compared it to eagle-owls from Asia, Europe and South America, and to Cape Eagle-Owl B capensis from Africa. He was apparently unaware of earlier descriptions of Spotted Eagle-Owl (Temminck 1821) or Greyish Eagle-Owl (Guérin-Méneville 1843). Sharpe had received his holotype from Colonel S B Miles, a British political agent and Consul in Muscat who travelled extensively in southern Arabia from 1872 to 1886. It is surprising that the specimen came from northern Oman, because nobody found the species there again for a century. There are probably no more than 25 pairs in northern Oman today (Jennings 2010). Elsewhere, the breeding range stretches from Dhofar in southern Oman through parts of Yemen to the western highlands of Saudi Arabia, much the same as that of Arabian Scops Owl Otus pamelae. This area has a relatively good supply of water, and consequently more woodland than the rest of Arabia.

In July 2013, Arnoud and Cecilia spent a week at Wadi Darbat in Dhofar, southern Oman. That year, the holy month of Ramadan coincided with the start of the monsoon. People remained at home in the evenings to break their fast, and nobody cared about the flooding on the Wadi Darbat road. Perhaps they also preferred to avoid the thick mist of stinging insects that emerge on monsoon nights. The pools on the road filled up with toads and at night, only the owls disturbed them. At every pool along the roadside they saw an owl perched in a tree, jumping down now and then to grab a toad. Arnoud and Cecilia were very lucky. It will be 12 years before Ramadan coincides with the monsoon again.

Arabian Eagle-Owl Bubo milesi, Wadi Darbat, Dhofar, Oman, 16 July 2013 (Arnoud B van den Berg). Perhaps same bird as in CD3-13.

During an earlier visit in April 2010, René and I heard many Arabian Eagle-Owls but saw none. In CD3-16, five Arabian are hooting, although two of them are almost inaudible. From about 0:50 onwards, there seems to be a loose duet between the nearest two birds, a lower-pitched one to the right and a higher-pitched one to the left of the microphones. Given the pitch difference, this may concern a male and a female. There is no real synchronisation, however, and a simple pitch difference between two males is difficult to rule out.

CD3-16: Arabian Eagle-Owl Bubo milesi Wadi Darbat, Dhofar, Oman, 19:52, 18 April 2010. Hooting of five individuals at dusk. Background: Arabian Scops Owl Otus pamelae. 100418.MR.195242.12

CD3-17 illustrates a different sound of Arabian Eagle-Owl recorded during that same April visit. The first time I heard these single-note, slightly nasal calls, they seemed to be given in reply to another individual that was hooting. In Eurasian Eagle-Owl B bubo, a similar but deeper and harsher call is the female’s soliciting call, heard especially around the time of egg-laying.

CD3-17: Arabian Eagle-Owl Bubo milesi Wadi Darbat, Dhofar, Oman, 19:41, 18 April 2010. Nasal-sounding calls, possibly soliciting calls of female. 100418.MR.194152.01

During our most recent visit in February 2014, the eagle-owls were very quiet. One windy evening, I put a microphone under a cliff from which a male had been calling four years earlier. As it became dark, I recorded a series of deep hoots given in flight (CD3-18). It could only have been an Arabian Eagle-Owl, although I have no idea what the sound ‘meant’.

CD3-18: Arabian Eagle-Owl Bubo milesi Wadi Darbat, Dhofar, Oman, 18:45, 21 February 2014. Series of hoots in flight at dusk. Background: Arabian Scops Owl Otus pamelae and Blackstart Oenanthe melanura. 140221.MR.184524.12

With this brief account, we have taken Arabian Eagle-Owl out of obscurity and shown that it sounds very different from its African relatives, but there is still a great deal to learn. For instance, we have not yet heard any juveniles. In Spotted Eagle-Owl, older young have a wheezing begging call (Laidler 2010), higher-pitched than that of Eurasian Eagle-Owl or indeed Pharaoh Eagle-Owl B ascalaphus, which also breeds in Arabia.

Arabian Eagle-Owl and Pharaoh Eagle-Owl probably know one another, but not very well. Where they meet, at least one of them is usually rare, and Arabian’s preference for wooded areas probably reduces contact to a minimum. When it happens, Pharaoh seems to dominate. Between 1986 and 1991 for example, Pharaoh replaced Arabian at all known breeding wadis near Taïf in Saudi Arabia (Martins & Hirschfeld 1998).

Studies of eagle-owls are not for the faint-hearted. Pharaoh Eagle-Owl is only slightly larger than Arabian Eagle-Owl but a lot more ferocious. In Morocco it is a known predator of Common Barn Owl Tyto alba (Thévenot 2006). So the Arabians of Taïf may not have been merely ‘replaced’. Should the opportunity arise, Bubo may well hunt Bubo.