I’ve lived in Poole most of my life. You would think that living in such a beautiful spot would have produced a mild natured man, content in his rustic idyll. Sadly not, and as friends sometimes complain, I’m just a bit combative. Especially when it comes to year listing in Poole Harbour.

If I can now take you back to 2000, the start of a new century, my ambition was a new start for the harbour. In 1994 Nigel Symes had won the coveted egret feather by recording 167 species in or from Poole Harbour, and in 1995 he won the feather again. Shaun took the year listing trophy in 1996 and 1997 with 187. Since then, Mo and I had matched his record, but now I wanted to beat it. I didn’t just want to beat it. I wanted 200 birds in Poole Harbour in 2000.

Year listing gets you out. It’s easy to sit indoors and sneer at listing but it does give the year purpose. Sometimes too much purpose.

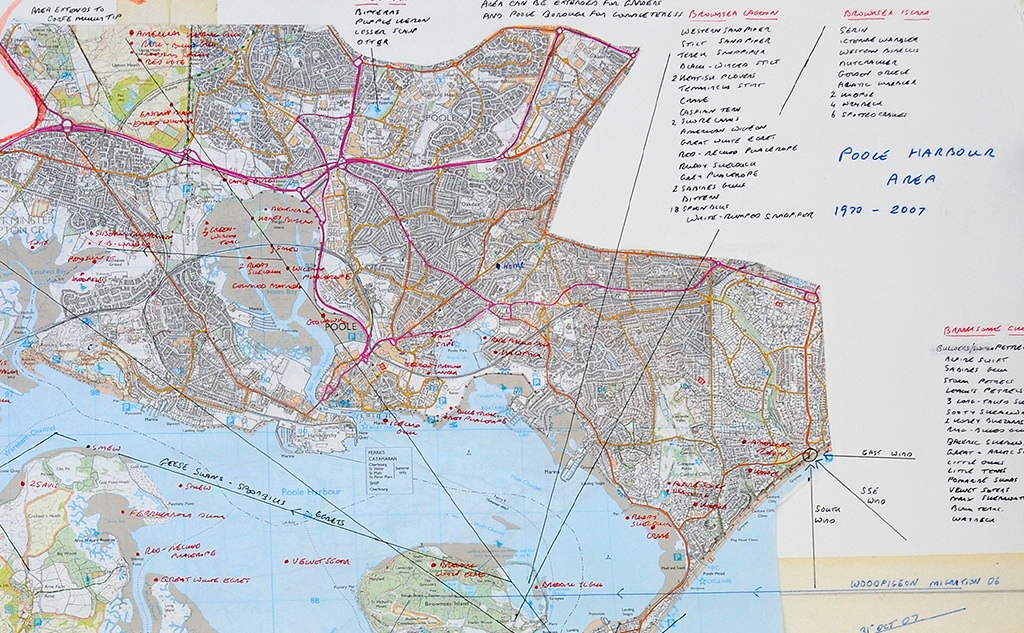

I had been cutting out and marking up maps with all the Wryneck records, Red Kite sightings, flight lines of Spoonbills, Hoopoe sightings, Spotted Crakes, and where Aquatic Warbler had been caught.

I was looking for insights into routes used by migrants passing through the area. I bought the new tide table and fisherman’s bait guide (the waders feed where the “bait” is), noted the states of the moon and the dates for the bird boats. Mo renewed our pager subscription and National Trust, RSPB and Dorset Naturalist Trust membership to give free parking, easy access to Brownsea, and to support the organisations responsible for some of Poole’s best habitat.

200 kg of wholesale bird table seed, ground food, niger seeds, cakes of fat, and peanuts arrived at the house. Ewan attracted flocks of Bramblings to his garden by grinding up peanuts, so our liquidiser was transferred to the shed. I was toying with the idea of playing reassuring finch sounds by the bird table. When I told Mo, she suggested I put out a menu.

New Year’s Day for me is the most exciting day of the year, better than my birthday, Christmas day, and certainly much better than New Year’s Eve. When I reflect, I have enjoyed my birthday parties almost as much as New Year’s Day birding, especially my 50th (50 hours of fun), when Shaun shouted the immortal words “I’ve never drunk till dawn before.” New Year’s Eve on the other hand is party time for amateurs, and I prefer to enjoy it quietly.

For me a big bird year traditionally starts with a brisk, bird filled January the first. Mo doesn’t see the point of running around in the dark trying to tick a bird you are going to see or hear all year. Having suffered cold and miserable January the firsts standing in freezing easterlies in the dark, waiting for a glimmer of dawn to see Purple Sandpipers feeding on the steps beside the Sandbanks car ferry, she believes it’s responsible for some of my worst craziness.

Purple Sandpiper Calidris maritima, North Haven, Poole Harbour, Dorset, 16 March 2010 (Nick Hopper)

It’s just the difference of a few hours, I argue. Instead of celebrating the arrival of the new year at midnight, it’s a celebration at six. Mo says it’s not six, it’s some hideous time around four or four thirty. Don’t get the wrong idea though. Mo is as competitive as any of the male birders, and at the time of writing has seen more birds in the harbour than any of them.

I can’t remember what sort of New Year’s Eve party we had that year, but I know the party was at our house, because our first record in the diary was a Collared Dove that was flushed by all the fireworks going off. We went to bed quite late because the next one was a “Robin singing 3am”.

Up at dawn, and as it was to be for much of the decade, the weather was mild. We wandered around the garden looking for Blackcaps. In a survey, a third of Dorset’s wintering Blackcaps were found in Poole gardens, up to nine of them in ours. They are thought to be from Belgium and Germany, and researchers there have discovered that the Blackcaps we have wintering in southern Britain are slightly different from those that winter in Spain. They have rounder wings and longer, narrower beaks. The males return to their central European breeding grounds earlier to claim territory and mate with females that have also wintered here. It seems that they are evolving into two distinct populations of Blackcap.

A walk down the track to the Middlebere hide, and we had ticked Graham Armstrong, Andy Humber, Phil Read, Jackie and Nick Hull, George Dunklin and the chap from the record shop out with his family. I told them all we were doing a year list and to please call my mobile if they found anything. Only 40% of local birders had mobiles then, and regular emails wouldn’t really get going until the next year. Always a great place, at Middlebere we saw Hen Harriers, a wintering Green Sandpiper and a rather jammy male Merlin dashing between the cottages.

On January the first, it’s traditional to try and see a Woodcock. You used to need cold weather, but Nick discovered a good site for winter flight views. At dusk he would wait beside the gate into the forest at the start of Soldier’s road, and watch Woodcock flying from the pines overhead into the wet fields and heath to feed.

They are one of our long distance migrants, shot at in every part of their range. A Woodcock caught and ringed at Lytchett in December was shot the following April, half way between Moscow and the Ural mountains, some 3,000 kilometres away. Anyway, we got our traditional tick around 17:30 as the sun was setting. Just as we were starting to shiver, a Woodcockk called and flew over our heads, silhouetted against the dying light.

Sunday 2 January saw Mo videoing a big flock of ducks on Little Sea with the idea that we would pop home and put them on our big telly screen for identification over a nice cup of tea. What if we did find a good duck and hadn’t actually seen it? We couldn’t really count it on our year list. For insurance, we looked through and found a Scaup and a Ruddy Duck.

Mo Constantine, Poole, Dorset, 21 August 2006 (Arnoud B van den Berg)

Ruddy Ducks are rare here and suffering a fiercely unpopular extermination programme. They were first seen locally when four turned up on 6 January 1979 at Poole Park, after the inland lakes had frozen. Since then, there have been around 30 records, and like our bird, which stayed for a month, they arrive during cold snaps or on a Saturday or Sunday morning when wildfowling disturbs them from their normal haunts. Now when one turns up, there is an unspoken news blackout to protect the few that remain.

6 January saw us at the Harrier Hide, watching a Barn Owl hunting over Wych creek. A few Rock Pipits winter there and at Lytchett Bay, and are occasionally trapped and ringed. Rees Cox was analysing one of the Holton Heath Barn Owl pellets when he discovered one of their rings inside it. Walking back to the road afterwards, four or five Woodcock flew over the track, calling as they headed into the fields from the wet bog, and Mo gave me that “I told you about January the first” look.

Telling Snipe from Jack Snipe and Woodcock by call at night is a dark art, and it comes in handy when you compete on year lists or bird races. Magnus had studied this, and sent me a little monograph 12 years ago. I suppose I should share it (especially as he has updated it):

“Dear Mark,

Here are my thoughts on separating Snipe and Woodcock flight sounds, I’ve included Jack Snipe for completeness. Common Snipe flight calls are well known to anyone who has walked through certain kinds of marshy ground at the appropriate time of year. Typically, a snipe we had not yet noticed because of its camouflage takes off at our feet with a whirring of wings, then gives a series of calls as it twists and turns away from us, towering high before descending into another part of the marsh, or disappearing as a spec in the distance. The calls we hear have a harsh, scratchy quality, a duration of around a tenth of a second, and an intonation that rises noticeably at the end, which is also the loudest part of the call. This ending is important, because Woodcock and Jack Snipe calls don’t have it. In CD2-92 you can hear calls given by a Common Snipe that was not flushed, but actually approaching the microphone.

The call most often given by Woodcocks in winter is similarly short, but keeps the same pitch from start to finish. An even simpler difference to remember between Common Snipe and Woodcock flight calls is the repetition rate. Common Snipe tend to give calls in sequences, at a rate of roughly one call per second, occasionally a bit more than a second, or nearly two. Woodcock usually repeats its winter flight call much more slowly, at about one call every four seconds (CD2-93), or gives just a single call.

Woodcocks are less likely to call when flushed, and so their flight calls are less well known. The best time to hear them in winter is when they are leaving the woods about half an hour after sunset. They will probably follow the same route every day, and once you locate it, you can go and check when they arrive in autumn, how their numbers change with winter temperatures, and when their numbers dwindle or they start displaying at the end of winter. The call described above is not their only winter call. If you are lucky, you may hear them giving a very strange ‘throbbing’ sound. I made several recordings of this sound in the Netherlands, all along the same flight route in January but over a period of four years. The first time I recorded it, I thought it might be the sound of a damaged wing beating, but in some recordings the wingbeats can be heard too, and they are about twice as fast (CD2-94). So the throbbing sound does appear to be a rapid series of calls. It is not very loud, has a reedy quality, and a ‘pulse rate’ of about four throbs per second.

CD2-92: Common Snipe Gallinago gallinago 20:50, 18 March 2008, Tory Island, Donegal, Ireland. Flight calls of a bird approaching the microphone. Background: Atlantic Ocean and Northern Lapwing Vanellus vanellus. 080318.MR.205016.01

CD2-93: Eurasian Woodcock Scolopax rusticola 18:01, 14 January 2005, Oostkapelle, Zeeland, Netherlands. Flight calls while leaving the woods at dusk, on the way to nocturnal feeding grounds. Background: Tundra Bean Goose Anser serrirostris and Western Jackdaw Corvus monedula. 04.045.MR.14901.11

CD2-94: Eurasian Woodcock Scolopax rusticola 17:51, 14 January 2005, Oostkapelle, Zeeland, Netherlands. ‘Throbbing’ of a Woodcock leaving the woods at dusk, on the way to nocturnal feeding grounds. Background: Western Jackdaw Corvus monedula. 04.045.MR.14308.11

Occasionally, Woodcocks in late winter can be heard to give a ‘sneeze’, which is identical to one of the sounds given during their

‘roding’ display. I have only recorded it twice given singly, so I am not sure about any possible repetition rate. However, in roding displays, this sound is heard about once every four seconds. In the example in CD2-95, there are some very faint low sounds before the sneeze with a rhythm and pitch similar to the deep, grumbling first part of the roding sound, so perhaps this was half-hearted roding from a bird not yet in the mood or condition to give a full display.

CD2-95: Eurasian Woodcock Scolopax rusticola 19:18, 12 March 2006, Oostkapelle, Zeeland, Netherlands. Single ‘sneeze’ of a presumed male, preceded by some very faint low sound. This may be an incipient ‘roding’ display of a bird not yet in full breeding condition. 06.001.MR.04328.01

In roding displays, the combination of the deep grumbling and the sneeze is given about once every four seconds. With its similar repetition rate, it seems very possible that the snipe-like winter call of Woodcock is related to this sneeze. Perhaps the sneeze, which includes some incredibly high frequencies, can only be given by adult males approaching breeding condition. During the breeding season and occasionally in late winter, Woodcocks often engage in courtship chases, in which the sneeze can be heard in combination with a lower-pitched sound, which is presumably given by females CD2-96). In such cases, the repetition rate of the sneeze notes is irregular, but typically much faster than in roding.

CD2-96: Eurasian Woodcock Scolopax rusticola 19:24, 12 March 2006, Oostkapelle, Zeeland, Netherlands. A chase flight involving three birds, with two of them giving very high-pitched ‘sneezes’, so presumably two males chasing a female. 06.001.MR.04924.01

Flight calls of Jack Snipe are similarly poorly known. For many birders, a lack of a flight call when flushed seems almost diagnostic for Jack Snipe. However, careful attention reveals that they often call when taking off, especially if there is more than one present. In my experience, if you do hear one calling as it takes off at your feet, you can be almost certain that there is another nearby. Those who have never noticed the flight call of Jack Snipe can be easily forgiven, because it is a weak sound, quieter than a Common Snipe, and the whirring of wings as a Jack Snipe takes off can drown it out. If you don’t stop moving immediately, the sound of your feet in the marshy vegetation could also quite easily mask the call, which is usually only given once or twice. Besides being quieter than Common Snipe, calls of Jack Snipe are lower-pitched and lack a distinctive ending. In CD2-97 you can hear how two Jack Snipe called when taking off.

CD2-97: Jack Snipe Lymnocryptes minimus 30 October 2002, IJmuiden, Noord-Holland, Netherlands. Two birds calling when flushed, part of a group of 14 that were concentrated in a small area. Six of them called as they took off in ones and twos. Background: Meadow Pipit Anthus pratensis and European Goldfinch Carduelis carduelis. 02.051.MR.13750.22

The commonest way to find a Jack Snipe is to flush one, whether accidentally or deliberately. If you know an area where there are likely to be Jack Snipe hiding by day, a good way to count them without disturbance is to wait till dusk, when they take off and fly to their feeding grounds. At this time, they are highly likely to call when taking off. The Jack Snipe in CD2-98 was recorded passing in a group of Common Snipe at dusk. Now you know what to listen for, see if you can pick it out.

Bye for now,

Magnus”

CD2-98: Jack Snipe Lymnocryptes minimus and Common Snipe Gallinago gallinago 25 March 2004, Texel, Noord-Holland, Netherlands. Three calls of a Jack Snipe flying over at dusk in a group of Common Snipe. Background: Common Blackbird Turdus merula. 04.009.MR.14740.12

Our home in 2000 contained our three teenage children and their friends and music mixing from every room. My contribution was a series of bird clocks all broadcasting a different bird sound on the stroke of every hour. I felt I was winning, then on Thursday 13 January on coming back from birding we found our teenage niece Anna sitting on our doorstep, having run away from home to live with us. At the same time there was a nice Brambling feeding on ‘Ewan’s’ scrambled peanuts on our lawn. We didn’t have much time to sort her out though (she stayed for a few years, bringing her own music, boyfriends and taste in alcohol), because Ewan had something else special for us.

While putting away an all day English breakfast in a beach café at Sandbanks, he’d noticed a Great Skua doing much the same. A juvenile, it was on the water eating a Herring Gull. After a while it flew to Pilot’s Point, where it preened for five minutes, then it was flushed by a walker and flew over our heads towards Brownsea and beyond. This monster took our list to 122.

Twitching now started in earnest, and we enjoyed being shown stuff. An Iceland Gull turned up at Hatch Pond on 22 January, a Saturday. We chased it… no luck, searched for it most of the next day… no luck. Then hooray. Stan found it a week later in Poole Park, looking Persil white sitting on the mud, so we cycled down and twitched it.

We met George Green at Middlebere, who told us there were Goosanders on Little Sea. Always a difficult bird, when we got there… nothing. Then a smart drake drifted out from behind the central spit where it had been sheltering from the westerly wind. By the end of the first month, we had seen 135 species in the harbour and the pace kept up like this until by mid-February we had seen 152.

Spring arrived, and we tested out some of my theories. Over the past few years, we had all visited Ballard Down but hadn’t found many local rarities. When I looked at my maps, Ballard had six, the most spectacular being a Gyrfalcon found on 5 February 1912 after a blizzard. Chatting with Stephen Smith, he pointed out that that Ballard faced east. We looked at the map together, and he suggested that the huge ridge of hills around the harbour was forming a barrier. Looking at the marked maps, wherever there was a gap in the hills there was a little cluster of rarity dots.

Part of Mark’s map of rarities and migration paths for Poole Harbour, Poole, Dorset, 20 August 2009 (Arnoud B van den Berg)

Stephen theorised that when flycatchers, redstarts and other spring migrants came into the harbour through the Ulwell gap, they saw heathland stretching out in front, and for some it was unappealing. He suggested that the green grass and trees of Greenlands farm might concentrate migrants in the same way as an oasis in the desert.

I wondered if it could have the same effect on rarer birds, and worked out that a Montagu’s Harrier, three Hoopoes, five Wrynecks, a Golden Oriole, an Icterine Warbler and a Rosy Starling had all been found in this area. Drawing a line from where the American Robin was found at Redhorn Point to the Arctic Redpoll spot on the edge of Spur Heath, and then to Brands Ford where six Bee-eaters were seen, created a rarity area that we called the Smith triangle. This theory was to substantially improve birding in the harbour. To prove the point, at Greenlands farm in the heart of the Smith triangle a lovely female Ring Ouzel sat out and looked beautiful, while a male hid in the bushes on 2 April.

I’d worked out that Montagu’s Harriers turn up in Poole Harbour between 5 and 23 May. Add a little Smith triangle theory and bingo: on 6 May as we sat drinking a thermos of tea, Mo spotted a second calendar-year female floating over the heath at the entrance to Greenlands farm.

The 187th species was Manx Shearwater, with 10 seen from Branksome Chine on 1 June, a new bird for my harbour list. Now that all the summer visitors were ticked, things slowed down and every new bird was hard won. I had a list of potential birds and rated them A, B or C dependant on their rarity. However, the next new bird was completely off the radar.

On 25 June, the day after Mo’s birthday, we were catching up with our work. I hadn’t really chosen the best year, as my business partner Andrew Gerrie had recently domiciled in Australia. He was due in for an overdue visit, but just as he arrived we had to excuse ourselves. A first-summer male Eastern Black-eared Wheatear had just turned up on Upton Heath! We rushed over there and saw it. Fortunately, our definition of Poole Harbour had been extended to include the heath, so it was just inside the area.

Rosy Starling Pastor roseus, juvenile, in flock of Common Starlings Sturnus vulgaris, Greenlands farm, Studland, Dorset, 3 October 2010 (Nick Hopper)

August is one of the best months in the harbour, and on Sunday 6 August Graham phoned us, having found a Wood Sandpiper on the ornamental lake in front of North Bestwall House at Swineham. It’s tricky peering over the shrubbery into the lake, as it looks as if you are trying to see someone in the house through your scope. In the end, we had to climb on top of a stile before we could find it tucked into the western corner of the lake, almost behind an island.

At Swineham there were over 100 Yellow-legged Gulls, and we flushed a Green Sandpiper. Wandering further, Mo found a Little Ringed Plover on the edge of the pit, then I saw a Ruddy Shelduck on the bank. Was it the wintering bird or a visitor? At this time of year it stood a better chance of being a genuine vagrant. We wandered off to Soldier’s Road then round to Greenlands farm. My son Jack phoned with news. “A Tawny Pipit in a field at Ower.” Wow, that would be the first for the harbour… We were there in minutes and joined the finder, Paul St Pierre.

There had been a fall, so we birded the area and found a few Spotted Flycatchers, a Pied Flycatcher and a Turtle Dove. Autumn had started with a bang, and one of the best days of the year saw us reach 191.

It’s traditional to see Curlew Sandpipers on Brownsea lagoon when adults pass through in the last days of August. Our first turned up on 27 August (taking us to 198). Shaun had organised a Big Bird Day for 3 September. We started at 03:30, but everything was overshadowed by a rarity. At around 09:00, Mo and I were seawatching lazily on the south side of Ballard, about 250 m up from Old Harry, when a Black Kite flew into view, being mobbed by a Carrion Crow. I didn’t get excited, because James Lidster had told me that there was an escaped Black Kite doing the rounds and I assumed this was it. I calmly noted the heavy moult, thinking “It’s an adult”. It flapped off, and despite us calling all the other guys, some of whom were close by, only Mo and I saw it. James explained later that it couldn’t have been the escaped bird, but I can’t remember why. That evening we caught up with a Ruff, the 116th bird for the day and most importantly the 200th bird of the year.

The next day, after two hours of searching, Mo rediscovered and I glimpsed the Wryneck that Graham had found on Rempstone heath, when it flew out of the heather and briefly perched on a post.

Now comes something very odd… At this time we didn’t know about any mass migration through the harbour, and on 30 September we left for a fortnight on Scilly with The Sound Approach. I had sketched out the ideas that would form the book The Sound Approach to birding (2006) for discussion. Not birding the harbour in October now 10 years on looks very foolish. I missed the great Honey Buzzard migration of that year, and also the Cliff Swallow at nearby Portland. (Arnoud can still remember the expression on my face when I heard the news. I was actually watching a Cliff Swallow on St Mary’s at the time!)

We had to wait until 2 November for a southerly gale, which produced a sighting of two British Storm Petrels in the waves off Branksome Chine, taking our very full list to 205. Towards the end of the year, work took over. On 7 November, Mo and I were at a large meeting when Shaun phoned to tell us that Hugo Wood-Homer had found a Long-billed Dowitcher at Wych lake, from the Harrier hide where we had been watching the Barn Owl at the beginning of the year. We shot down there, and as we searched unsuccessfully three male Hen Harriers headed to their roost. The next day we were in London. We finally saw it on 9 November.

American Cliff Swallow Petrochelidon pyrrhonota, juvenile, Hugh, St Mary’s, Scilly, 28 September 2000 (Arnoud B van den Berg). ‘The one in England that Mark did see…’

The weather turned very nasty, and after 12 fruitless days of seawatching, a dark-morph immature Pomarine Skua flew west past Branksome Chine with 12 Little Gulls taking our final score to 207. Now I had to clean the list. As Poole Harbour is in Dorset, we have to use the British Ornithologists’ Union list, which doesn’t include White Wagtail and Pale-bellied Brent Goose. Green-winged Teal has since been accepted as a full species, but wasn’t one back then. That’s minus three.

When a record is rejected it feels like a kick in the teeth. No matter how it is explained, “Liar liar pants on fire” rings in your ears, followed by indignation and often a long period of sulking. It’s a measure of the birder how he copes with it.

Now if you look in British Birds 93 (11, 2000) you will see: “We were not convinced that the identification was fully established”; “rejected…” “Black Kite, Ballard Down 3rd September 2000.”

I may have ranted about this decision. I may even have sulked. Finally today, to lay a ghost to rest, I phoned Nick and then Shaun and asked what they thought of our Black Kite record.

My heart was in my mouth, but both said, “It’s all right Mark we believe you”.